This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2007) |

The history of the punk subculture involves the history of punk rock, the history of various punk ideologies, punk fashion, punk visual art, punk literature, dance, and punk film. Since emerging in the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia in the mid-1970s, the punk subculture has spread around the globe and evolved into a number of different forms. The history of punk plays an important part in the history of subcultures in the 20th century.

Antecedents and influences

editSeveral precursors have had varying degrees of influence on the punk subculture.

Art and philosophy

editA number of philosophical and artistic movements were influences on and precursors to the punk movement. The most overt is anarchism, especially its artistic inceptions. The cultural critique and strategies for revolutionary action offered by the Situationist International in the 1950s and 1960s were an influence on the vanguard of the British punk movement, particularly the Sex Pistols. Pistols manager Malcolm McLaren consciously embraced situationist ideas, which are also reflected in the clothing designed for the band by Vivienne Westwood and the visual artwork of the Situationist-affiliated Jamie Reid, who designed many of the band's graphics. Nihilism also had a hand in the development of punk's careless, humorous, and sometimes bleak character.

Several strains of modern art anticipated and influenced punk. The relationship between punk rock and popular music has a clear parallel with the irreverence Dadaism held for the project of high art. If not a direct influence, futurism, with its interests in speed, conflict, and raw power foreshadowed punk culture in a number of ways. Minimalism furnished punk with its simple, stripped-down, and straightforward style. Another source of punk's inception was pop art. Andy Warhol and his Factory studio played a major role in setting up what would become the New York punk scene. Pop art also influenced the look of punk visual art. In more recent times, postmodernism has made headway into the punk scene.

Literature and film

editVarious writers, books, and literary movements were important to the formation of the punk subculture. Poet Arthur Rimbaud provided the basis for Richard Hell's attitude, fashion, and hairstyle. Charles Dickens' working class politics and unromantic depictions of disenfranchised street youth influenced British punk in a number of ways. Malcolm McLaren described the Sex Pistols as Dickensian.

Punk was influenced by the Beat generation, especially Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and William S. Burroughs. Kerouac's On the Road gave Jim Carroll the impetus to write The Basketball Diaries, perhaps the first example of punk literature. George Orwell's dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four might have inspired much of punk's distrust for the government. In his autobiography No Dogs, No Blacks, No Irish!, John Lydon remembers the influence that film version of A Clockwork Orange had on his own style. John Waters' 1972 underground classic, Pink Flamingos, is considered an important precursor of punk culture.[1][2]

Music

editOne of the earliest known precursors of the punk subculture in music is that of Woody Guthrie who often wrote songs about anti-fascism and the conditions faced by working-class people. Beginning in the 1930s and becoming popular in the 1940s, Guthrie is often known as one of the first punks.[3][4][5][6]

Punk rock has a variety of origins. Garage rock was the first form of music called "punk",[7] and indeed that style influenced much of punk rock. Punk rock was also a reaction against tendencies that had overtaken popular music in the 1970s, including what the punks saw as "bombastic" forms of heavy metal, progressive rock and "arena rock" as well as "superficial" disco music (although in the UK, many early Sex Pistols fans such as the Bromley Contingent and Jordan quite liked disco, often congregating at nightclubs such as Louise's in Soho and the Sombrero in Kensington. The track "Love Hangover" by Diana Ross, the house anthem at the former, was cited as a particular favourite by many early UK Punks.)[8] The British punk movement also found a precedent in the "do-it-yourself" attitude of the Skiffle craze that emerged amid the post-World War II austerity of 1950s Britain.

In addition to the inspiration of those "garage bands" of the 1960s, the roots of punk rock draw on the snotty attitude, on-stage and off-stage violence, and aggressive instrumentation of the Who, the Kinks, the Sonics, the early Rolling Stones, and rockers of the late 1950s rockers such as Eddie Cochran and Gene Vincent; the abrasive, dissonant mental breakdown style of the Velvet Underground; the sexuality, political confrontation, and on-stage violence of Detroit bands Alice Cooper, the Stooges and MC5; the English pub rock scene and political UK underground bands such as Mick Farren and the Deviants; the New York Dolls; and some British "glam rock" or "art rock" acts of the early 1970s, including T.Rex, David Bowie, Gary Glitter and Roxy Music. Influence from other musical genres, including reggae, funk, and rockabilly can also be detected in early punk rock.

Earlier subcultures

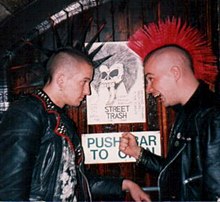

editPrevious youth subcultures influenced various aspects of the punk subculture. The punk movement rejected the remnants of the hippie counterculture of the 1960s while at the same time preserving its distaste for the mainstream. Punk fashion rejected the loose clothes, and bell-bottomed appearances of hippie fashion.[citation needed] At the same time, punks rejected the long hair adopted by hippies in favor of short, choppy haircuts, especially in the Britain as a follow on from the precursor Mod, Skinhead and the late sixties/early 70s Bootboy hairstyle fashions.[citation needed] The hippie crash pad found a new inception as punk houses. The jeans, T-shirts, chains, and leather jackets common in punk fashion can be traced back to the bikers, rockers and greasers of earlier decades. The all-black attire and moral laxity of some Beatniks influenced the punk movement. Other subcultures that influenced the punk subculture, in terms of fashion, music attitude or other factors include: Teddy Boys, Mods, skinheads and glam rockers.[citation needed] In 1991, Observer journalist John Windsor wrote a story about artist Frankie Stein – Precursor to Punk, observing that she was wearing a safety pin as earring some years before her friends in SexPistols picked it up and experimented in tandem with Sassoon artistic director Flint Whincop with hairstyles copied by people in her circle such as Toya, Steve Strange and what became The Sex Pistols.

Origins

editThe phrase "punk rock" (from "punk", meaning a beginner or novice[9][citation needed]), was originally applied to the untutored guitar-and-vocals-based rock and roll of United States bands of the mid-1960s such as The Standells, The Sonics, and the Seeds, bands that now are more often categorized as "garage rock". The earliest known example of a rock journalist using the term was Greg Shaw who used it to describe music of The Guess Who in the April 1971 issue of Rolling Stone, which he refers to as "good, not too imaginative, punk rock and roll". Dave Marsh also used the term in the May 1971 issue of Creem in reference to music by ? and the Mysterians.[10] The term was mainly used by rock music journalists in the early 1970s to describe 60s garage bands and more contemporary acts influenced by them.[7][11] In the liner notes of the 1972 anthology album Nuggets, critic and guitarist Lenny Kaye uses the term "punk-rock" to refer to the mid-60s garage rock groups, as well as some of the darker and more primitive practitioners of 1960s psychedelic rock.[7]

The next step in punk's early development, retroactively named protopunk, arose in the north-eastern United States in cities such as Detroit, Boston, and New York. Bands such as the Velvet Underground, the Stooges, MC5, and the Dictators, coupled with shock rock acts like Alice Cooper, laid the foundation for punk in the US. The transgender community of New York inspired the New York Dolls, who led the charge as glam punk developed out of the wider glam rock movement. The drug subculture of Manhattan, especially heroin users, formed the fetal stage of the New York punk scene. Art punk, exemplified by Television, grew out of the New York underworld of drug addicts and artists shortly after the emergence of glam punk.

Shortly after the time of those notes, Lenny Kaye (who had written the Nuggets liner notes) formed a band with avant-garde poet Patti Smith. Smith's group, and her first album, Horses, released in 1975, directly inspired many of the mid-1970s punk rockers, so this suggests one path by which the term migrated to the music we now know as punk. There's a bit of controversy which isn't mentioned. The term punk was used to define the emerging movement was when posters saying "PUNK IS COMING! WATCH OUT!" were posted around New York City. Also, Punk Magazine would use the term and help popularize it. From this point on, punk would emerge as a separate and distinct subculture with its own identity, ideology, and sense of style.

Economic recession, including a garbage strike, instilled much dissatisfaction with life among the youth of industrial Britain. Punk rock in Britain coincided with the end of the era of post-war consensus politics that preceded the rise of Thatcherism, and nearly all British punk bands expressed an attitude of angry social alienation. Los Angeles was also facing economic hard times. A collection of art school students and a thriving drug underground caused Los Angeles to develop one of the earliest punk scenes.

The original punk subculture was made up of a loose affiliation of several groups that emerged at separate times under different circumstances. There was significant cross-pollination between these subcultures, and some were derivative of others. Most of these subcultures are still extant, while others have since gone extinct. These subcultures interacted in various ways to form the original mainline punk subculture, which varied greatly from region to region.

New York

editThe first ongoing music scene that was assigned the "punk" label appeared in New York in 1974–1976 centered around bands that played regularly at the clubs Max's Kansas City and CBGB. This had been preceded by a mini underground rock scene at the Mercer Arts Center, picking up from the demise of the Velvet Underground, starting in 1971 and featuring the New York Dolls and Suicide, which helped to pave the way, but came to an abrupt end in 1973 when the building collapsed.[12] The CBGB and Max's scene included the Ramones, Television, Blondie, Patti Smith, Johnny Thunders (a former New York Doll) and the Heartbreakers, Richard Hell and the Voidoids and Talking Heads. The "punk" title was applied to these groups by early 1976, when Punk Magazine first appeared, featuring these bands alongside articles on some of the immediate role models for the new groups, such as Lou Reed, who was on the cover of the first issue of Punk, and Patti Smith, cover subject on the second issue.

At the same time, a less celebrated, but nonetheless highly influential, scene had appeared in Ohio, including the Electric Eels, Devo and Rocket from the Tombs, who in 1975 split into Pere Ubu and the Dead Boys. Malcolm McLaren, then manager of the New York Dolls, spotted Richard Hell and decided to bring Hell's look back to Britain.[citation needed]

London

editWhile the London bands may have played a relatively minor role in determining the early punk sound,[citation needed] the London punk scene would come to define and epitomize the rebellious punk culture. After a brief stint managing the New York Dolls at the end of their career in the US, Englishman Malcolm McLaren returned to London in May 1975. With Vivienne Westwood, he started a clothing store called SEX that was instrumental in creating the radical punk clothing style. He also began managing The Swankers, who would soon become the Sex Pistols. The Sex Pistols soon created a strong cult following in London, centered on a clique known as the Bromley Contingent (named after the suburb where many of them had grown up), who followed them around the country.

An oft-cited moment in punk rock's history is a 4 July 1976 concert by the Ramones at the Roundhouse in London (The Stranglers were also on the bill). Many of the future leaders of the UK punk rock scene were inspired by this show, and almost immediately after it, the UK punk scene got into full swing. By the end of 1976, many fans of the Sex Pistols had formed their own bands, including the Clash, Siouxsie and the Banshees, the Adverts, Generation X, the Slits and X-Ray Spex. Other UK bands to emerge in this milieu included The Damned (the first to release a single, the classic "New Rose"), the Jam, The Vibrators, Buzzcocks and the appropriately named London.

In December 1976, the Sex Pistols, The Clash, The Damned and Johnny Thunders & the Heartbreakers united for the Anarchy Tour, a series of gigs throughout the UK. Many of the gigs were canceled by venue owners, after tabloid newspapers and other media seized on sensational stories regarding the antics of both the bands and their fans. The notoriety of punk rock in the UK was furthered by a televised incident that was widely publicized in the tabloid press; appearing on a London TV show called Thames Today, guitarist Steve Jones of the Sex Pistols was goaded into a verbal altercation by the host, Bill Grundy, swearing at him on live television in violation of at the time accepted standards of propriety.

One of the first books about punk rock—The Boy Looked at Johnny by Julie Burchill and Tony Parsons (December 1977)—declared the punk movement to be already over: the subtitle was The Obituary of Rock and Roll. The title echoed a lyric from the title track of Patti Smith's 1975 album Horses.

Elsewhere

editDuring this same period, bands that would later be recognized as "punk" were formed independently in other locations, such as the Saints in Brisbane, Australia, the Modern Lovers in Boston, and the Stranglers and the Sex Pistols in London. These early bands also operated within small "scenes", often facilitated by enthusiastic impresarios who either operated venues, such as clubs, or organized temporary venues. In other cases, the bands or their managers improvised their own venues, such as a house inhabited by The Saints in an inner suburb of Brisbane. The venues provided a showcase and meeting place for the emerging musicians (the 100 Club in London, CBGB in New York, and The Masque in Hollywood are among the best known early punk clubs).

SFR Yugoslavia

editThe former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was not a member of the Eastern Bloc, but a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement. Maintaining a more liberal communist system, sometimes referred to as Titoism, Yugoslavia was more opened to Western influences comparing to the other communist states. Hence, starting from the 1950s onwards, a well-developed Yugoslav rock scene was able to emerge with all its music genres and subgenres including punk rock, heavy metal and so on. The Yugoslav punk bands were the first punk rock acts ever to emerge in a communist country.

Notable artists included: the pioneers Pankrti, Paraf and Pekinška patka (the first two formed in 1977, the latter in 1978), the 1980s hardcore punk acts: KUD Idijoti, Niet, KBO! and many others. Many bands from the first generation signed record contracts with major labels such as Jugoton, Suzy Records and ZKP RTL and often appeared on TV and in the magazines, however some preferred independent labels and the DIY ethos. From punk rock emerged the new wave and some bands, such as Prljavo kazalište and Električni orgazam decided to affiliate with it, becoming top acts of the Yugoslav new wave scene. The Yugoslav punk music also included social commentary, which was generally tolerated, however there were certain cases of censorship and some punks faced occasional problems with the authorities.

The scene ceased to exist with the Yugoslav Wars in the 1990s, and its former artists continued their work in the independent countries that emerged after the breakup of Yugoslavia, where many of them were involved in anti-war activities and often clashed with the domestic chauvinists. Since the end of the wars and the departure of the nationalist leaders, the music scenes in the ex-Yugoslav countries re-established their former cooperation. The Yugoslav punk is considered an important part of the former Yugoslav culture, not only that it influenced the formation of the once vibrant Yugoslav new wave scene but also it gave inspiration to some authentic domestic movements such as New Primitives and others.[13][14][15]

Spain

editIn Spain, the punk rock scene emerged in 1978, when the country had just emerged from forty years of fascist dictatorship under General Franco, a state that "melded state repression with fundamentalist Catholic moralism". Even after Franco died in 1975, the country went through a "volatile political period", in which the country had to try to relearn democratic values, and install a constitution. When punk emerged, it "did not appropriate socialism as its goal"; instead, it embraced "nihilism", and focused on keeping the memories of past abuses alive, and accusing all of Spanish society of collaborating with the fascist regime.[16]

The early punk scene included a range of marginalized and outcast people, including workers, unemployed, leftists, anarchists, queens, dykes, poseurs, scroungers, and petty criminals. The scenes varied by city. In Madrid, which had been the power center of Franco's Falangist party, the punk scene was like "a release valve" for the formerly repressed youth. In Barcelona, a city which had a particularly "marginalized status under Franco", because he suppressed the area's "Catalan language and culture", the youth felt an "exclusion from mainstream society" that enabled them to come together and form a punk subculture.[16]

The first independently released Spanish punk disc was a 45 RPM record by Almen TNT in 1979. The song, which sounded like the US band The Stooges stated that no one believed in revolution anymore, and it criticized the emerging consumer culture in Spain, as people flocked to the new department stores. The early Spanish punk records, most of which emerged in the explosion of punk in 1978, often reached back to "old-fashioned 50s rocknroll to glam to early metal to Detroit’s hard proto-punk", creating an aggressive mix of fuzz guitar, jagged sounds, and crude Spanish slang lyrics.[16]

Late 1970s: diversification

editIn 1977, a second wave of bands emerged, influenced by those mentioned above. Some, such as the Misfits (from New Jersey), the Exploited (from Scotland), GBH (from England) Black Flag (from Los Angeles), Stiff Little Fingers (from Northern Ireland) and Crass (from Essex) would go on to influence the move away from the original sound of punk rock, that would spawn the Hardcore subgenre.

Gradually punk became more varied and less minimalist with bands such as the Clash incorporating other musical influences like reggae and rockabilly and jazz into their music. In the UK, punk interacted with the Jamaican reggae and ska subcultures. The reggae influence is evident in much of the music of the Clash and the Slits, for example. By the end of the 1970s, punk had spawned the 2 Tone ska revival movement, including bands such as the Beat (the English Beat in U.S.), the Specials, Madness and the Selecter.

The message of punk remained subversive, counter-cultural, rebellious, and politically outspoken. Punk rock dealt with topics such as problems facing society, oppression of the lower classes, the threat of a nuclear war, or it delineated the individual's personal problems, such as being unemployed, or having particular emotional and/or mental issues, i.e. depression. Punk rock was a message to society that all was not well and all were not equal. While it is thought that the style of punk from the 1970s had a decline in the 1980s, many subgenres branched off playing their own interpretation of punk rock. Anarcho-punk become a style in its own right. Nazi punk arose as the radical right wing of punk.

1980s: further diversification

editAlthough most of the prominent bands in the genre pre-dated the 1980s by a few years, it was not until the 1980s that journalist Garry Bushell gave the subgenre "Oi!" its name, partly derived from the Cockney Rejects song "Oi! Oi! Oi!". This movement featured bands such as Cock Sparrer, Cockney Rejects, Blitz, and Sham 69. Bands sharing the Ramones' bubblegum pop influences formed their own brand of punk, sporting melodic songs and lyrics more often dealing with relationships and simple fun than most punk rock's nihilism and anti-establishment stance. These bands, the founders of pop punk, included the Ramones, Buzzcocks, the Rezillos and Generation X.

As the punk movement began to lose steam, post-punk, new wave, and no wave took up much of the media's attention. In the UK, meanwhile, diverse post-punk bands emerged, such as Joy Division, Throbbing Gristle, Gang of Four, Siouxsie and the Banshees & Public Image Ltd, the latter two bands featuring people who were part of the original British punk rock movement.

Sometime around the beginning of the 1980s, punk underwent a renaissance as the hardcore punk subculture emerged. This subculture proved fertile in much the same way as the original punk subculture, producing several new groups. These subcultures stand alongside the older subcultures under the punk banner. The United States saw the emergence of hardcore punk, which is known for fast, aggressive beats and political lyrics. It can be argued, though, that Washington, D.C. was the site of hardcore punk's first emergence.

Early hardcore bands include Dead Kennedys, Black Flag, Bad Brains, the Descendents, the Replacements, and the Germs, and the movement developed via Minor Threat, the Minutemen, and Hüsker Dü, among others. In New York, there was a large hardcore punk movement led by bands such as Agnostic Front, the Cro-Mags, Murphy's Law, Sick of It All, and Gorilla Biscuits. Other styles emerged from this new genre including skate punk, emo, and straight edge.

Alternative and indie legacy

editThe underground punk movement in the United States in the 1980s produced countless bands that either evolved from a punk rock sound or claimed to apply its spirit and DIY ethics to a completely different sound. By the end of the 1980s these bands had largely eclipsed their punk forebears and were termed alternative rock. As alternative bands like Sonic Youth and the Pixies were starting to gain larger audiences, major labels sought to capitalize on a market that had been growing underground for the past 10 years.

In 1991, Nirvana achieved huge commercial success with their album, Nevermind. Nirvana cited punk as a key influence on their music. Although they tended to label themselves as punk rock and championed many unknown punk icons (as did many other alternative rock bands), Nirvana's music was equally akin to other forms of garage or indie rock and heavy metal that had existed for decades. Nirvana's success kick-started the alternative rock boom that had been underway since the late 1980s, and helped define that segment of the 1990s popular music milieu. The subsequent shift in taste among listeners of rock music was chronicled in a film entitled 1991: The Year Punk Broke, which featured Nirvana, Dinosaur Jr, and Sonic Youth; Nirvana also featured in the film Hype! (U.S.CHAOS).

1990s: American revival

editA new movement in the mainstream became visible in the early and mid-1990s, claiming to be a form of punk, this was characterized by the scene at 924 Gilman Street, a venue in Berkeley, California, which featured bands such as Operation Ivy, Green Day, Rancid and later bands including AFI, (though clearly not simultaneously, as Rancid included members of Operation Ivy, who had broken up 2 years prior to the formation of Rancid).

Epitaph Records, an independent record label started by Brett Gurewitz of Bad Religion, would become the home of the "skate punk" sound, characterized by bands like the Offspring, Pennywise, NOFX, and the Suicide Machines, many bands arose claiming the mantle of the ever-diverse punk genre—some playing a more accessible, pop style and achieving commercial success. The late 1990s also saw another ska punk revival. This revival continues into the 2000s with bands like Streetlight Manifesto, Reel Big Fish, and Less Than Jake.

Pop punk

editThe commercial success of alternative rock also gave way to another style which mainstream media claimed to be a form of "punk", dubbed pop punk or "mall punk" by the press; this new movement gained success in the mainstream. Examples of bands labeled "pop punk" by MTV and similar media outlets include; Blink 182, Simple Plan, Good Charlotte, and Sum 41.

By the late 1990s, punk was so ingrained in Western culture that it was often used to sell commercial bands as "rebels", amid complaints from punk rockers that, by being signed to major labels and appearing on MTV, these bands were buying into the system that punk was created to rebel against, and as a result, could not be considered true punk (though clearly, punk's earliest pioneers, such as the Clash and the Sex Pistols also released work via the major labels).

2000s and 2010s

editThere is still a thriving punk scene in North America, Australia, Asia and Europe. The widespread availability of the Internet and file sharing programs enables bands who would otherwise not be heard outside of their local scene to garner larger followings, and is in keeping with punk's DIY ethic. It has allowed a rise in interaction between punk scenes in different places and subgenres, as evidenced by events such as Fluff Fest in the Czech Republic, which brings together DIY punk enthusiasts from across Europe.[17]

Footnotes

edit- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (18 April 1997). "Pink Flamingos". Entertainment Weekly. Time Inc. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- ^ Smithey, Cole (13 July 2014). "Capsules: Pink Flamingos". Cole Smithey. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- ^ Bear, John (1 November 2022). "Dropkick Murphys on "Proto-Punk" Woody Guthrie, Who Wrote "Shipping Up to Boston"". westword.com.

When Woody Guthrie emblazoned "This Machine Kills Fascists" across the top of his guitar in the '40s and belted out tunes such as "All You Fascists Bound to Lose," he became the first punk rocker.

- ^ Taylor, Tom (14 July 2023). "The life and times of Woody Guthrie – the world's first punk". faroutmagazine.co.uk. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ Kot, Greg (9 May 2012). "Tom Morello keeps punk-rock spirit of Woody Guthrie alive". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ "Billy Bragg Discusses Woody Guthrie's Punk Side". MTV. 10 July 1998. Archived from the original on 21 March 2024. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ a b c [L. Kaye, liner notes to Nuggets LP compilation. Elektra Records. 1972]

- ^ England's Dreaming, Jon Savage Faber & Faber 1991, pp 93, 95, 185–186

- ^ "Punk". Merriam-Webster Online. Retrieved 6 August 2010.

- ^ D. Marsh, review of ? & The Mysterians. Creem. May, 1971

- ^ [G. Shaw. Rolling Stone, 4 Jan. 1973]

- ^ From the Velvets to the Voidoids: A Pre-Punk History for a Post-Punk World by Clinton Heylin, 1993, Penguin Books, ISBN 0-14-017970-4

- ^ Dragan Pavlov and Dejan Šunjka: Punk u Jugoslaviji (Punk in Yugoslavia), publisher: IGP Dedalus, 1990 (in Serbian, Croatian, and Slovene)

- ^ Janjatović, Petar. Ilustrovana Enciklopedija YU Rocka 1960–1997 (Illustrated Encyclopedia of YU ROCK), publisher: Geopoetika, 1997 Archived 11 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine (in Serbian)

- ^ Interview with Igor Vidmar at Uzurlikzurli e-zine (in English)

- ^ a b c Drogas, Sexo, Y Un Dictador Muerto: 1978 on Vinyl in Spain. SHIT FI dot. http://www.shit-fi.com/Articles/Spain1978/Spain1978.htm

- ^ Sanna, Jacopo (20 September 2017). "The Sincere and Vibrant World of the Czech DIY Scene". Bandcamp. Retrieved 7 October 2017.