William Holman Hunt OM (2 April 1827 – 7 September 1910) was an English painter and one of the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. His paintings were notable for their great attention to detail, vivid colour, and elaborate symbolism. These features were influenced by the writings of John Ruskin and Thomas Carlyle, according to whom the world itself should be read as a system of visual signs. For Hunt it was the duty of the artist to reveal the correspondence between sign and fact. Of all the members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Hunt remained most true to their ideals throughout his career. He was always keen to maximise the popular appeal and public visibility of his works.[1]

William Holman Hunt | |

|---|---|

Self-portrait, 1867, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence | |

| Born | 2 April 1827 London, England |

| Died | 7 September 1910 (aged 83) London, England |

| Occupation | Painter |

| Movement | Orientalist; Pre-Raphaelites |

| Spouses |

|

| Signature | |

Biography

editBorn at Cheapside, City of London, as William Hobman Hunt, to warehouse manager William Hunt (1800–1856) and Sarah (c. 1798–1884), daughter of William Hobman, of Rotherhithe[2] Hunt adopted the name "Holman" instead of "Hobman" when he discovered that a clerk had misspelled the name that way after his baptism at the Anglican church of Saint Mary the Virgin, Ewell. The Hobman family were wealthy, and it was thought that Sarah had made an unequal marriage.[3][4] After eventually entering the Royal Academy art schools, having initially been rejected, Hunt rebelled against the influence of its founder Sir Joshua Reynolds. He formed the Pre-Raphaelite movement in 1848, after meeting the poet and artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Along with John Everett Millais they sought to revitalise art by emphasising the detailed observation of the natural world in a spirit of quasi-religious devotion to truth. This religious approach was influenced by the spiritual qualities of medieval art, in opposition to the alleged rationalism of the Renaissance embodied by Raphael. He had many pupils including Robert Braithwaite Martineau.

Hunt married twice. After a failed engagement to his model Annie Miller, in 1861 he married Fanny Waugh, who later modelled for the figure of Isabella. When, at the end of 1866, she died in childbirth in Italy, he sculpted her tomb at Fiesole, having it brought down to the English Cemetery in Florence, beside the tomb of Elizabeth Barrett Browning.[5] He had a close connection with St. Mark's Church in Florence, and paid for the communion chalice inscribed in memory of his wife. His second wife, Edith, was Fanny's youngest sister. At the time it was illegal in Great Britain to marry one's deceased wife's sister, so the two of them travelled abroad and married at Neuchâtel (in francophone Switzerland) in November 1875.[6] This led to a grave conflict with other family members, notably his former Pre-Raphaelite colleague Thomas Woolner, who had once been in love with Fanny and had married the middle sister, Alice Waugh.

Hunt's works were not initially successful, and were widely attacked in the art press for their alleged clumsiness and ugliness.[citation needed] He achieved some early note for his intensely naturalistic scenes of modern rural and urban life, such as The Hireling Shepherd and The Awakening Conscience. However, it was for his religious paintings that he became famous, initially The Light of the World (1851–1853), now in the chapel at Keble College, Oxford, England; a later version (1900) toured the world and now has its home in St Paul's Cathedral, London. Hunt worked at his home in Prospect Place (now Cheyne Walk), Chelsea, London.[7]

In the mid-1850s Hunt travelled to the Holy Land in search of accurate topographical and ethnographical material for further religious works, and to employ his "powers to make more tangible Jesus Christ's history and teaching";[8] there he painted The Scapegoat, The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple, and The Shadow of Death, along with many landscapes of the region. Hunt also painted many works based on poems, such as Isabella and The Lady of Shalott. He eventually built his own house in Jerusalem.[9]

He eventually had to abandon painting because failing eyesight meant that he could not achieve the quality that he wanted. His last major works, including a large version of The Light of the World hanging in St Paul's Cathedral, London, were completed with the help of his assistant, Edward Robert Hughes.

Holman Hunt lived and had a studio at 18 Melbury Road in Holland Park, West London, from 1903 until his death.[10][11] He died on 7 September 1910 and was buried at St Paul's Cathedral in London.

Awards and commemoration

editHunt published an autobiography in 1905.[12] Many of his late writings are attempts to control the interpretation of his work. That year, he was appointed to the Order of Merit by King Edward VII. At the end of his life, he lived in Sonning-on-Thames. 18 Melbury Road has a blue plaque commemorating Hunt, added in 1923.[13]

Hunt's personal life was the subject of Diana Holman-Hunt's book My Grandfather, his Life and Loves.[14]

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was depicted in two BBC period dramas. The first, The Love School, in 1975, starred Bernard Lloyd as Hunt. The second was Desperate Romantics, in which Hunt is played by Rafe Spall.[15]

Facing Mar Elias Monastery is a stone bench erected by the wife of the painter, who painted some of his major works at this spot. The bench is inscribed with biblical verses in Hebrew, Greek, Arabic and English.

Partial list of works

edit- A Converted British Family Sheltering a Christian Missionary from the Persecution of the Druids (1850)

- Valentine Rescuing Sylvia from Proteus (1851)

- The Awakening Conscience (1853)

- The Light of the World (1854)

- The Scapegoat (1856)

- The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple (1860)

- The Shadow of Death (1871)

- The Importunate Neighbour (1895)

- The Miracle of the Holy Fire (1899)

- The Triumph of the Innocents (1876-87) which is displayed at the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool.

Gallery

edit-

The Lantern Maker's Courtship, A Street Scene in Cairo (1854–56)

-

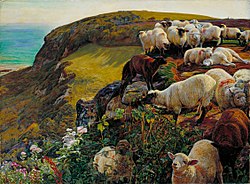

The Hireling Shepherd (1851)

-

The Scapegoat (1856)

-

Portrait of Fanny Holman Hunt (1866–67)

-

The Birthday (1868)

-

Amaryllis (1884)

-

The Lady of Shalott (between 1888 and 1905)

-

May Morning on Magdalen Tower (1890)

-

Christ and the two Marys (1847 and 1897)

See also

edit| External videos | |

|---|---|

| Hunt's Claudio and Isabella, Smarthistory | |

| Hunt's The Awakening Conscience, Smarthistory |

References

edit- ^ Judith Bronkhurst, 'Hunt, William Holman (1827–1910)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004

- ^ Bronkhurst, Judith (2004). "Hunt, William Holman (1827–1910), painter". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/34058. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "William Holman Hunt Biography". www.thehistoryofart.org.

- ^ Amor, Anne Clark (1989). William Holman Hunt: the True Pre-Raphaelite. London: Constable. pp. 14–15. ISBN 0094687706.

- ^ Jess Waugh (compiler) (31 March 2013). "Tomb of Fanny Waugh Hunt (There are several pictures of it if you scroll down the page.)". Pre-Rafaelite Tombs at the English Cemetery in Florence. Jess Waugh Ltd., NY. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- ^ Brian Bouchard (compiler) (2011). "William Holman Hunt (1827–1910)". Pre-Raphaelite artist and his connections to Ewell. Epsom and Ewell Local and Family History Centre. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- ^ "Settlement and building: Artists and Chelsea Pages 102-106 A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 12, Chelsea". British History Online. Victoria County History, 2004. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ Hunt, W.H., Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood; London: Macmillan; 1905, Vol. 1, p. 349

- ^ "William Holman Hunt's House and Studio in Jerusalem". victorianweb.org.

- ^ Banerjee, Jacqueline. "The Home and Studio of William Holman Hunt in Holland Park". The Victorian Web. Retrieved 31 August 2023.

- ^ "W. Holman Hunt, 18 Melbury Road, Kensington, W., to [Sir Edward] Poynter". RA Collection: Archive. UK: Royal Academy of Arts. 7 January 1906. Retrieved 31 August 2023.

- ^ "Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood". Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 20 July 2007.

- ^ "Holman-Hunt, William, O.M. (1827–1910)". UK: English Heritage. Retrieved 31 August 2023.

- ^ British watercolours in the Victoria and Albert Museum. Victoria and Albert Museum. 1980. ISBN 9780856671111. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ^ BBC Archived 1 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine, BBC Drama Production presents Desperate Romantics for BBC Two

Further reading

edit- Landow, George (1979). William Holman Hunt and Typological Symbolism. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-02196-8.

- Maas, Jeremy (1984). Holman Hunt and the Light of the World. Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-85967-683-0.

- Bronkhurst, Judith (2006). William Holman Hunt : A Catalogue Raisonné. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10235-2.

- Lochnan, Katharine (2008). Holman Hunt and the Pre-Raphaelite Vision. Art Gallery of Toronto. ISBN 978-1-894243-57-5.

External links

edit- 55 artworks by or after William Holman Hunt at the Art UK site

- William Holman Hunt's The Scapegoat: Rite of Forgiveness/Transference of Blame

- Works by Holman Hunt at Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery's Pre-Raphaelite Online Resource

- William Holman Hunt Collection. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

- Holman Hunt Manuscripts, John Rylands Library, University of Manchester

- Archival Material at Leeds University Library