Erik Weisz (March 24, 1874 – October 31, 1926), known as Harry Houdini (/huːˈdiːni/ hoo-DEE-nee), was a Hungarian-American escape artist, illusionist, and stunt performer noted for his escape acts.[3]

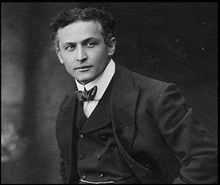

Harry Houdini | |

|---|---|

Houdini in 1907 | |

| Born | Erik Weisz March 24, 1874 |

| Died | October 31, 1926 (aged 52) Detroit, Michigan, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Peritonitis[1] |

| Resting place | Machpelah Cemetery |

| Occupations | |

| Years active | 1891–1926 |

| Height | 5 ft 6 in (168 cm) |

| Spouse | [2] |

| Relatives | Theodore Hardeen (brother) |

| Signature | |

Houdini first attracted notice in vaudeville in the United States and then as Harry "Handcuff" Houdini on a tour of Europe, where he challenged police forces to keep him locked up. Soon he extended his repertoire to include chains, ropes slung from skyscrapers, straitjackets under water, and having to escape from and hold his breath inside a sealed milk can with water in it.

In 1904, thousands watched as Houdini tried to escape from special handcuffs commissioned by London's Daily Mirror, keeping them in suspense for an hour. Another stunt saw him buried alive and only just able to claw himself to the surface, emerging in a state of near-breakdown. While many suspected that these escapes were faked, Houdini presented himself as the scourge of fake spiritualists, pursuing a personal crusade to expose their fraudulent methods. As president of the Society of American Magicians, he was keen to uphold professional standards and expose fraudulent artists. He was also quick to sue anyone who imitated his escape stunts.

Houdini made several movies but quit acting when it failed to bring in money. He was also a keen aviator and became the first man to fly a powered aircraft in Australia, on March 18, 1910 at Diggers Rest, a field roughly 20 miles (32 km) from Melbourne.[4]

Early life

editErik Weisz was born in Budapest, Kingdom of Hungary to a Jewish family.[5][6] His parents were Rabbi Mayer Sámuel Weisz (1829–1892) and Cecília Steiner (1841–1913). Houdini was one of seven children: Herman M. (1863–1885), who was Houdini's half-brother by Rabbi Weisz's first marriage; Nathan J. (1870–1927); Gottfried William (1872–1925); Theodore (1876–1945);[7] Leopold D. (1879–1962); and Carrie Gladys (1882–1959),[8] who was left almost blind after a childhood accident.[9]

Weisz arrived in the United States on July 3, 1878, on the SS Frisia with his mother (who was pregnant) and his four brothers.[10] The family changed their name to the German spelling Weiss, and Erik became Ehrich. The family lived in Appleton, Wisconsin, where his father served as rabbi of the Zion Reform Jewish Congregation.

According to the 1880 census, the family lived on Appleton Street in an area that is now known as Houdini Plaza.[11] On June 6, 1882, Rabbi Weiss became an American citizen. Losing his job at Zion in 1882, Rabbi Weiss and family moved to Milwaukee and fell into dire poverty.[12] In 1887, Rabbi Weiss moved with Erik to New York City, where they lived in a boarding house on East 79th Street. He was joined by the rest of the family once Rabbi Weiss found permanent housing. As a child, Erik Weiss took several jobs, making his public début as a nine-year-old trapeze artist, calling himself "Ehrich, the Prince of the Air". He was also a champion cross country runner in his youth.

Magic career

editWhen Weisz became a professional magician he began calling himself "Harry Houdini", after the French magician Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin, after reading Robert-Houdin's autobiography in 1890. Weiss incorrectly believed that an i at the end of a name meant "like" in French. However, "i" at the end of the name means "belong to" in Hungarian. In later life, Houdini claimed that the first part of his new name, Harry, was an homage to American magician Harry Kellar, whom he also admired, though it was likely adapted from "Ehri", a nickname for "Ehrich", which is how he was known to his family.[13]

When he was a teenager, Houdini was coached by the magician Joseph Rinn at the Pastime Athletic Club.[14]

Houdini began his magic career in 1891, but had little success.[15] He appeared in a tent act with strongman Emil Jarrow.[16] He performed in dime museums and sideshows, and even doubled as "The Wild Man" at a circus. Houdini focused initially on traditional card tricks. At one point, he billed himself as the "King of Cards".[17] Some – but not all – professional magicians would come to regard Houdini as a competent but not particularly skilled sleight-of-hand artist, lacking the grace and finesse required to achieve excellence in that craft.[18][19] He soon began experimenting with escape acts.[citation needed]

In the early 1890s, Houdini was performing with his brother "Dash" (Theodore) as "The Brothers Houdini".[20]: 160 The brothers performed at the Chicago World's Fair in 1893 before returning to New York City and working at Huber's Dime Museum for "near-starvation wages".[20]: 160 In 1894, Houdini met a fellow performer, Wilhelmina Beatrice "Bess" Rahner. Bess was initially courted by Dash, but she and Houdini married, with Bess replacing Dash in the act, which became known as "The Houdinis". For the rest of Houdini's performing career, Bess worked as his stage assistant.

Houdini's big break came in 1899 when he met manager Martin Beck in St. Paul, Minnesota. Impressed by Houdini's handcuffs act, Beck advised him to concentrate on escape acts and booked him on the Orpheum vaudeville circuit. Within months, he was performing at the top vaudeville houses in the country. In 1900, Beck arranged for Houdini to tour Europe. After some days of unsuccessful interviews in London, Houdini's British agent Harry Day helped him to get an interview with C. Dundas Slater, then manager of the Alhambra Theatre. He was introduced to William Melville and gave a demonstration of escape from handcuffs at Scotland Yard.[21] He succeeded in baffling the police so effectively that he was booked at the Alhambra for six months. His show was an immediate hit and his salary rose to $300 a week (equivalent to $10,987 in 2023).[22]

Between 1900 and 1920 he appeared in theatres all over Great Britain performing escape acts, illusions, card tricks and outdoor stunts, becoming one of the world's highest paid entertainers.[23] He also toured the Netherlands, Germany, France, and Russia and became widely known as "The Handcuff King". In each city, Houdini challenged local police to restrain him with shackles and lock him in their jails. In many of these challenge escapes, he was first stripped nude and searched. In Moscow, he escaped from a Siberian prison transport van,[20]: 163 claiming that, had he been unable to free himself, he would have had to travel to Siberia, where the only key was kept.

In Cologne, Houdini sued a police officer, Werner Graff, who alleged that he made his escapes via bribery.[24] Houdini won the case when he opened the judge's safe (he later said the judge had forgotten to lock it). With his new-found wealth, Houdini purchased a dress said to have been made for Queen Victoria. He then arranged a grand reception where he presented his mother in the dress to all their relatives. Houdini said it was the happiest day of his life. In 1904, Houdini returned to the U.S. and purchased a house for $25,000 (equivalent to $847,778 in 2023), a brownstone at 278 W. 113th Street in Harlem, New York City.[25]

While on tour in Europe in 1902, Houdini visited Blois with the aim of meeting the widow of Emile Houdin, the son of Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin, for an interview and permission to visit his grave. He did not receive permission but still visited the grave.[26] Houdini believed that he had been treated unfairly and later wrote a negative account of the incident in his magazine, claiming he was "treated most discourteously by Madame W. Emile Robert-Houdin".[26] In 1906, he sent a letter to the French magazine L'Illusionniste stating: "You will certainly enjoy the article on Robert Houdin I am about to publish in my magazine. Yes, my dear friend, I think I can finally demolish your idol, who has so long been placed on a pedestal that he did not deserve."[27]

In 1906, Houdini created his own publication, the Conjurers' Monthly Magazine.[28] It was a competitor to The Sphinx, but was short-lived and only two volumes were released until August 1908. Magic historian Jim Steinmeyer has noted that "Houdini couldn't resist using the journal for his own crusades, attacking his rivals, praising his own appearances, and subtly rewriting history to favor his view of magic."[29]

From 1907 and throughout the 1910s, Houdini performed with great success in the United States. He freed himself from jails, handcuffs, chains, ropes, and straitjackets, often while hanging from a rope in sight of street audiences. Because of imitators, Houdini put his "handcuff act" behind him on January 25, 1908, and began escaping from a locked, water-filled milk can. The possibility of failure and death thrilled his audiences. Houdini also expanded his repertoire with his escape challenge act, in which he invited the public to devise contraptions to hold him. These included nailed packing crates (sometimes lowered into water), riveted boilers, wet sheets, mail bags,[30] and even the belly of a whale that had washed ashore in Boston. Brewers in Scranton, Pennsylvania, and other cities challenged Houdini to escape from a barrel after they filled it with beer.[31]

Many of these challenges were arranged with local merchants in one of the first uses of mass tie-in marketing. Rather than promote the idea that he was assisted by spirits, as did the Davenport Brothers and others, Houdini's advertisements showed him making his escapes via dematerializing, although Houdini himself never claimed to have supernatural powers.[32]

After much research, Houdini wrote a collection of articles on the history of magic, which were expanded into The Unmasking of Robert-Houdin published in 1908. In this book he attacked his former idol Robert-Houdin as a liar and a fraud for having claimed the invention of automata and effects such as aerial suspension, which had been in existence for many years.[33][34] Many of the allegations in the book were dismissed by magicians and researchers who defended Robert-Houdin. Magician Jean Hugard would later write a full rebuttal to Houdini's book.[35][36][37]

Houdini introduced the Chinese Water Torture Cell at the Circus Busch in Berlin, Germany, on September 21, 1912.[38] He was suspended upside-down in a locked glass-and-steel cabinet full to overflowing with water, holding his breath for more than three minutes. He would go on performing this escape for the rest of his life.

During his career, Houdini explained some of his tricks in books written for the magic brotherhood. In Handcuff Secrets (1909), he revealed how many locks and handcuffs could be opened with properly applied force, others with shoestrings. Other times, he carried concealed lockpicks or keys. When tied down in ropes or straitjackets, he gained wiggle room by enlarging his shoulders and chest, moving his arms slightly away from his body.[32]

His straitjacket escape was originally performed behind curtains, with him popping out free at the end. Houdini's brother (who was also an escape artist, billing himself as Theodore Hardeen) discovered that audiences were more impressed when the curtains were eliminated so they could watch him struggle to get out. On more than one occasion, they both performed straitjacket escapes while dangling upside-down from the roof of a building in the same city.[32]

For most of his career, Houdini was a headline act in vaudeville. For many years, he was the highest-paid performer in American vaudeville. One of Houdini's most notable non-escape stage illusions was performed at the New York Hippodrome, when he vanished a full-grown elephant from the stage.[39] He had purchased this trick from the magician Charles Morritt.[40][41] In 1923, Houdini became president of Martinka & Co., America's oldest magic company. The business is still in operation today.

He also served as president of the Society of American Magicians (a.k.a. S.A.M.) from 1917 until his death in 1926. Founded on May 10, 1902, in the back room of Martinka's magic shop in New York, the Society expanded under the leadership of Harry Houdini during his term as national president from 1917 to 1926. Houdini was magic's greatest visionary: He sought to create a large, unified national network of professional and amateur magicians. Wherever he traveled, he gave a lengthy formal address to the local magic club, made speeches, and usually threw a banquet for the members at his own expense. He said "The Magicians Clubs as a rule are small: they are weak ... but if we were amalgamated into one big body the society would be stronger, and it would mean making the small clubs powerful and worthwhile. Members would find a welcome wherever they happened to be and, conversely, the safeguard of a city-to-city hotline to track exposers and other undesirables".

For most of 1916, while on his vaudeville tour, Houdini had been recruiting – at his own expense – local magic clubs to join the S.A.M. in an effort to revitalize what he felt was a weak organization. Houdini persuaded groups in Buffalo, Detroit, Pittsburgh, and Kansas City to join. As had happened in London, he persuaded magicians to join. The Buffalo club joined as the first branch, (later assembly) of the Society. Chicago Assembly No. 3 was, as the name implies, the third regional club to be established by the S.A.M., whose assemblies now number in the hundreds. In 1917, he signed Assembly Number Three's charter into existence, and that charter and this club continue to provide Chicago magicians with a connection to each other and to their past. Houdini dined with, addressed, and got pledges from similar clubs in Detroit, Rochester, Pittsburgh, Kansas City, Cincinnati and elsewhere. This was the biggest movement ever in the history of magic. In places where no clubs existed, he rounded up individual magicians, introduced them to each other, and urged them into the fold.

By the end of 1916, magicians' clubs in San Francisco and other cities that Houdini had not visited were offering to become assemblies. He had created the richest and longest-surviving organization of magicians in the world. It now embraces almost 6,000 dues-paying members and almost 300 assemblies worldwide. In July 1926, Houdini was elected for the ninth successive time President of the Society of American Magicians. Every other president has only served for one year. He also was President of the Magicians' Club of London.[42]

In the final years of his life (1925/26), Houdini launched his own full-evening show, which he billed as "Three Shows in One: Magic, Escapes, and Fraud Mediums Exposed".[43]

Notable escapes

editDaily Mirror challenge

editIn 1904, the London Daily Mirror newspaper challenged Houdini to escape from special handcuffs that it claimed had taken Nathaniel Hart, a locksmith from Birmingham, five years to make. Houdini accepted the challenge for March 17 during a matinée performance at London's Hippodrome theatre. It was reported that 4000 people and more than 100 journalists turned out for the much-hyped event.[44] The escape attempt dragged on for over an hour, during which Houdini emerged from his "ghost house" (a small screen used to conceal the method of his escape) several times. At one point he asked if the cuffs could be removed so he could take off his coat. The Mirror representative, Frank Parker, refused, saying Houdini could gain an advantage if he saw how the cuffs were unlocked. Houdini promptly took out a penknife and, holding it in his teeth, used it to cut his coat from his body. Some 56 minutes later, Houdini's wife appeared on stage and gave him a kiss. Many thought that in her mouth was the key to unlock the special handcuffs. However, it has since been suggested that Bess did not in fact enter the stage at all, and that this theory is unlikely due to the size of the six-inch key.[45] Houdini then went back behind the curtain. After an hour and ten minutes, Houdini emerged free. As he was paraded on the shoulders of the cheering crowd, he broke down and wept. At the time, Houdini said it had been one of the most difficult escapes of his career.[46]

After Houdini's death, his friend Martin Beck was quoted in Will Goldston's book, Sensational Tales of Mystery Men, admitting that Houdini was bested that day and had appealed to his wife, Bess, for help. Goldston goes on to claim that Bess begged the key from the Mirror representative, then slipped it to Houdini in a glass of water. It was stated in the book The Secret Life of Houdini that the key required to open the specially designed Mirror handcuffs was six inches long, and could not have been smuggled to Houdini in a glass of water. Goldston offered no proof of his account, and many modern biographers have found evidence (notably in the custom design of the handcuffs) that the Mirror challenge may have been arranged by Houdini and that his long struggle to escape was pure showmanship.[47] James Randi believes that the only way the handcuffs could have been opened was by using their key, and speculates that it would have been viewed "distasteful" to both the Mirror and to Houdini if Houdini had failed the escape.[20]: 165

This escape was discussed in depth on the Travel Channel's Mysteries at the Museum in an interview with Houdini expert, magician and escape artist Dorothy Dietrich of Scranton's Houdini Museum.[48]

A full-sized construction of the same Mirror Handcuffs, as well as a replica of the Bramah style key for them, are on display to the public at The Houdini Museum in Scranton, Pennsylvania.[49][50] This set of cuffs is believed to be one of only six in the world, some of which are not on display.[51]

Milk Can Escape

editIn 1908, Houdini introduced his own original act, the Milk Can Escape.[52]: 175–178 In this act, Houdini was handcuffed and sealed inside an oversized milk can filled with water and made his escape behind a curtain. As part of the effect, Houdini invited members of the audience to hold their breath along with him while he was inside the can. Advertised with dramatic posters that proclaimed "Failure Means A Drowning Death", the escape proved to be a sensation.[52]: 177 Houdini soon modified the escape to include the milk can being locked inside a wooden chest, being chained or padlocked. Houdini performed the milk can escape as a regular part of his act for only four years, but it has remained one of the acts most associated with him. Houdini's brother, Theodore Hardeen, continued to perform the milk can escape and its wooden chest variant[53] into the 1940s.

The American Museum of Magic has the milk can and overboard box used by Houdini.[54]

After other magicians proposed variations on the Milk Can Escape, Houdini claimed that the act was protected by copyright and in 1906, brought a case against John Clempert, one of the most persistent imitators. The matter was settled out of court and Clempert agreed to publish an apology.[55]

Chinese water torture cell

editAround 1912, the vast number of imitators prompted Houdini to replace his milk can act with the Chinese water torture cell. In this escape, Houdini's feet were locked in stocks, and he was lowered upside down into a tank filled with water. The mahogany and metal cell featured a glass front, through which audiences could clearly see Houdini. The stocks were locked to the top of the cell, and a curtain concealed his escape. In the earliest version of the torture cell, a metal cage was lowered into the cell, and Houdini was enclosed inside that. While making the escape more difficult – the cage prevented Houdini from turning – the cage bars also offered protection should the front glass break.

The original cell was built in England, where Houdini first performed the escape for an audience of one person as part of a one-act play he called "Houdini Upside Down". This was done to obtain copyright protection for the effect, and establish grounds to sue imitators – which he did. While the escape was advertised as "The Chinese Water Torture Cell" or "The Water Torture Cell", Houdini always referred to it as "the Upside Down" or "USD". The first public performance of the USD was at the Circus Busch in Berlin, on September 21, 1912. Houdini continued to perform the escape until his death in 1926.[32]

Suspended straitjacket escape

editOne of Houdini's most popular publicity stunts was to have himself strapped into a regulation straitjacket and suspended by his ankles from a tall building or crane. Houdini would then make his escape in full view of the assembled crowd. In many cases, Houdini drew tens of thousands of onlookers who brought city traffic to a halt. Houdini would sometimes ensure press coverage by performing the escape from the office building of a local newspaper. In New York City, Houdini performed the suspended straitjacket escape from a crane being used to build the subway. After flinging his body in the air, he escaped from the straitjacket. Starting from when he was hoisted up in the air by the crane, to when the straitjacket was completely off, it took him two minutes and thirty-seven seconds. There is film footage in the Library of Congress of Houdini performing the escape.[56] Films of his escapes are also shown at The Houdini Museum in Scranton, Pennsylvania.

After being battered against a building in high winds during one escape, Houdini performed the escape with a visible safety wire on his ankle so that he could be pulled away from the building if necessary. The idea for the upside-down escape was given to Houdini by a young boy named Randolph Osborne Douglas (March 31, 1895 – December 5, 1956), when the two met at a performance at Sheffield's Empire Theatre.[32]

Overboard box escape

editAnother of Houdini's most famous publicity stunts was to escape from a nailed and roped packing crate after it had been lowered into water. He first performed the escape in New York's East River on July 7, 1912. Police forbade him from using one of the piers, so he hired a tugboat and invited press on board. Houdini was locked in handcuffs and leg-irons, then nailed into the crate which was roped and weighed down with two hundred pounds of lead. The crate was then lowered into the water. He escaped in 57 seconds. The crate was pulled to the surface and found still to be intact, with the manacles inside.

Houdini performed this escape many times, and even performed a version on stage, first at Hamerstein's Roof Garden where a 5,500-US-gallon (21,000 L) tank was specially built, and later at the New York Hippodrome.[57]

Buried alive stunt

editHoudini performed at least three variations on a buried alive stunt during his career. The first was near Santa Ana, California in 1915, and it almost cost him his life. Houdini was buried, without a casket, in a pit of earth six feet deep. He became exhausted and panicked while trying to dig his way to the surface and called for help. When his hand finally broke the surface, he fell unconscious and had to be pulled from the grave by his assistants. Houdini wrote in his diary that the escape was "very dangerous" and that "the weight of the earth is killing".[58][59]

Houdini's second variation on buried alive was an endurance test designed to expose mystical Egyptian performer Rahman Bey, who had claimed to use supernatural powers to remain in a sealed casket for an hour. Houdini bettered Bey on August 5, 1926, by remaining in a sealed casket, or coffin, submerged in the swimming pool of New York's Hotel Shelton for one and a half hours. Houdini claimed he did not use any trickery or supernatural powers to accomplish this feat, just controlled breathing.[60] He repeated the feat at the YMCA in Worcester, Massachusetts on September 28, 1926, this time remaining sealed for one hour and eleven minutes.[61]

Houdini's final buried alive was an elaborate stage escape that featured in his full evening show. Houdini would escape after being strapped in a straitjacket, sealed in a casket, and then buried in a large tank filled with sand. While posters advertising the escape exist (playing off the Bey challenge by boasting "Egyptian Fakirs Outdone!"), it is unclear whether Houdini ever performed buried alive on stage. The stunt was to be the feature escape of his 1927 season, but Houdini died on October 31, 1926. The bronze casket Houdini created for buried alive was used to transport Houdini's body from Detroit to New York following his death on Halloween.[62]

Film career

editIn 1906, Houdini started showing films of his outside escapes as part of his vaudeville act. In Boston, he presented a short film called Houdini Defeats Hackenschmidt. Georg Hackenschmidt was a famous wrestler of the day, but the nature of their contest is unknown as the film is lost.[63] In 1909, Houdini made a film in Paris for Cinema Lux titled Merveilleux Exploits du Célèbre Houdini à Paris (Marvellous Exploits of the Famous Houdini in Paris).[64] It featured a loose narrative designed to showcase several of Houdini's famous escapes, including his straitjacket and underwater handcuff escapes. That same year Houdini got an offer to star as Captain Nemo in a silent version of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas, but the project never made it into production.[65]

It is often erroneously reported that Houdini served as special-effects consultant on the Wharton/International cliffhanger serial The Mysteries of Myra, shot in Ithaca, New York, because Harry Grossman, director of The Master Mystery also filmed a serial in Ithaca at about the same time. The consultants on the serial were pioneering Hereward Carrington and Aleister Crowley.[66]

In 1918, Houdini signed a contract with film producer B. A. Rolfe to star in a 15-part serial, The Master Mystery (released in November 1918). As was common at the time, the film serial was released simultaneously with a novel. Financial difficulties resulted in B. A. Rolfe Productions going out of business, but The Master Mystery led to Houdini being signed by Famous Players–Lasky Corporation/Paramount Pictures, for whom he made two pictures, The Grim Game (1919) and Terror Island (1920).[67]

The Grim Game was Houdini's first full-length movie and is reputed to be his best. Because of the flammable nature of nitrate film and their low rate of survival, film historians considered the film lost. One copy did exist hidden in the collection of a private collector only known to a tiny group of magicians that saw it. Dick Brookz and Dorothy Dietrich of The Houdini Museum in Scranton, Pennsylvania, had seen it twice on the invitation of the collector. After many years of trying, they finally got him to agree to sell the film to Turner Classic Movies,[68] who restored the complete 71-minute film. The film, not seen by the general public for 96 years, was shown by TCM on March 29, 2015, as a highlight of their yearly 4-day festival in Hollywood.[69]

While filming an aerial stunt for The Grim Game, two biplanes collided in mid-air with a stuntman doubling Houdini dangling by a rope from one of the planes. Publicity was geared heavily toward promoting this dramatic "caught-on-film" moment, claiming it was Houdini himself dangling from the plane. While filming these movies in Los Angeles, Houdini rented a home in Laurel Canyon. Following his two-picture stint in Hollywood, Houdini returned to New York and started his own film production company called the "Houdini Picture Corporation". He produced and starred in two films, The Man from Beyond (1921) and Haldane of the Secret Service (1923). He also founded his own film laboratory business called The Film Development Corporation (FDC), gambling on a new process for developing motion picture film. Houdini's brother, Theodore Hardeen, left his own career as a magician and escape artist to run the company. Magician Harry Kellar was a major investor.[70] In 1919 Houdini moved to Los Angeles to film. He resided in 2435 Laurel Canyon Boulevard, a residence owned by Ralph M. Walker. The Houdini Estate, a tribute to Houdini, is located on 2400 Laurel Canyon Boulevard, previously home to Walker himself.[71] The Houdini Estate is subject to controversy, in that it is disputed whether Houdini ever actually made it his home. While there are claims it was Houdini's house, others counter that "he never set foot" on the property. It is rooted in Bess's parties or seances, etc. held across the street, she would do so at the Walker mansion. In fact, the guesthouse featured an elevator connecting to a tunnel that crossed under Laurel Canyon to the big house grounds (though capped, the tunnel still exists).[72]

Neither Houdini's acting career nor FDC found success, and he gave up on the movie business in 1923, complaining that "the profits are too meager".

In April 2008, Kino International released a DVD box set of Houdini's surviving silent films, including The Master Mystery, Terror Island, The Man From Beyond, Haldane of the Secret Service, and five minutes from The Grim Game. The set also includes newsreel footage of Houdini's escapes from 1907 to 1923, and a section from Merveilleux Exploits du Célébre Houdini à Paris, although it is not identified as such.[73]

Aviator

editIn 1909, Houdini became fascinated with aviation. He purchased a French Voisin biplane for $5,000 (equivalent to $163,500 in 2023) from the Chilean aviators José Luis Sánchez-Besa and Emilio Eduardo Bello,[74][75][76] and hired a full-time mechanic, Antonio Brassac. After crashing once, he made his first successful flight on November 26 in Hamburg, Germany.[77]

The following year, Houdini toured Australia and brought along his Voisin biplane with the intention to be the first person to fly in Australia.

- Melbourne people will shortly have an opportunity of witnessing the ascent of a flying machine, for Houdini, whose Voision [sic] bi-plane has arrived, has determined to make a flight before his season closes at the [New] Opera House [in Melbourne, at the end of March]. The 60 to 80 horse-power motor used is of the E.N.V. pattern. The machine has been erected at Diggers' Rest. Table Talk, March 3, 1910.[78]

Australian flights

editMarch 18, 1910

editOn Friday, March 18, 1910, following more than a month of delays due to inclement weather conditions,[79][80] Houdini completed one of the first powered aeroplane flights ever made in Australia. He made three flights in his French Voisin biplane, at the Old Plumpton Paddock, at Diggers Rest, Victoria, ranging from 1 minute to 3½ minutes – reaching an altitude of 100 ft in one of his flights, and travelling more than two miles in another.[81][82] Nine of the 30 spectators present on that day signed a certificate verifying Houdini's achievement.[83][84]

March 20, 1910

editHampered by the windy conditions on the Saturday, and unable to fly safely, Houdini took to the air again early on Sunday morning, 20 March 20, 1910:

- After a short preliminary flight, lasting 26 sec., Houdini took wing again, and, amid loud applause from the hundred or more spectators, who were on the ground, described three circles at altitudes, varying from 20ft to over 100ft, covering a distance of between three and four miles in 3min 45½sec. The Argus, 21 March 1910.[85]

March 21, 1910

editOn Monday morning, 21 March 1910, some 30 spectators witnessed Houdini make an extended flight at Diggers Rest of 7min. 37secs., covering at least 6 miles, at altitudes ranging from 20 ft. to 100 ft. Australian aviator Basil Watson's father, mother, and younger sister, Venora, were among the spectators; and their names were included in the list of 16 spectator signatures on the certificate that verified Houdini's achievement.[86][87]

After Australia

editAfter completing his Australia tour, Houdini put the Voisin into storage in England. He announced he would use it to fly from city to city during his next music hall tour and even promised to leap from it handcuffed, but he never flew again.[88]

Debunking spiritualists

editIn the 1920s, Houdini turned his energies toward debunking psychics and mediums in order to show how they were taking advantage of the bereaved,[20]: 166 a pursuit that was in line with the debunkings by stage magicians since the late nineteenth century.[90]

Houdini's training in magic allowed him to expose frauds who had successfully fooled many scientists and academics. He was a member of a Scientific American committee that offered a cash prize to any medium who could successfully demonstrate supernatural abilities. None were able to do so, and the prize was never collected. The first to be tested was medium George Valiantine of Wilkes Barre, Pennsylvania. As his fame as a "medium-buster" grew, Houdini took to attending séances in disguise, accompanied by a reporter and a police officer. Possibly the most famous medium he debunked was Mina Crandon, also known as "Margery".[91]

Joaquín Argamasilla, known as the "Spaniard with X-ray Eyes", claimed to be able to read handwriting or numbers on dice through closed metal boxes. In 1924, he was exposed by Houdini as a fraud. Argamasilla peeked through his simple blindfold and lifted up the edge of the box so he could look inside it without others noticing.[92] Houdini also investigated the Italian medium Nino Pecoraro, who he considered to be fraudulent.[93]

Houdini's exposure of phony mediums inspired other magicians to follow suit, including The Amazing Randi, Dorothy Dietrich, Penn & Teller, and Dick Brookz.[94]

Houdini chronicled his debunking exploits in his book, A Magician Among the Spirits, co-authored with C. M. Eddy, Jr., who was not credited. These activities compromised Houdini's friendship with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Doyle, a firm believer in spiritualism during his later years, refused to give credence to any of Houdini's exposés. Doyle came to believe that Houdini was a powerful spiritualist medium and had performed many of his stunts by means of paranormal abilities and was using those abilities to block the powers of the mediums that he was supposedly debunking.[95] This disagreement led to the two men becoming public antagonists and Doyle came to view Houdini as a dangerous enemy.[32]

Before Houdini died, he and his wife agreed that if Houdini found it possible to communicate after death, he would communicate the message "Rosabelle believe", a secret code which they agreed to use. "Rosabelle" was their favorite song. Bess held yearly séances on Halloween for ten years after Houdini's death. She did claim to have contact through Arthur Ford in 1929 when Ford conveyed the secret code, but Bess later said the incident had been faked. The code seems to have been such that it could be broken by Ford or his associates using existing clues.[32] Evidence to this effect was discovered by Ford's biographer after he died in 1971.[96] In 1936, after a last unsuccessful séance on the roof of the Knickerbocker Hotel, she put out the candle that she had kept burning beside a photograph of Houdini since his death. In 1943, Bess said that "ten years is long enough to wait for any man."

The tradition of holding a séance for Houdini continues, held by magicians throughout the world. The Official Houdini Séance was organized in the 1940s[97] by Sidney Hollis Radner, a Houdini aficionado from Holyoke, Massachusetts.[98] Yearly Houdini séances are also conducted in Chicago at the Excalibur nightclub by "necromancer" Neil Tobin on behalf of the Chicago Assembly of the Society of American Magicians;[99] and at the Houdini Museum in Scranton by magician Dorothy Dietrich, who previously held them at New York's Magic Towne House with such magical notables as Houdini biographers Walter B. Gibson and Milbourne Christopher. Gibson was asked by Bess Houdini to carry on the original séance tradition. After doing them for many years at New York's Magic Towne House, before he died, Walter passed on the tradition of conducting of the Original Séances to Dorothy Dietrich.[94]

In 1926, Harry Houdini hired H. P. Lovecraft and his friend C. M. Eddy, Jr., to write an entire book about debunking religious miracles, which was to be called The Cancer of Superstition. Houdini had earlier asked Lovecraft to write an article about astrology, for which he paid $75 (equivalent to $1,291 in 2023). The article does not survive. Lovecraft's detailed synopsis for Cancer does survive, as do three chapters of the treatise written by Eddy. Houdini's death derailed the plans, as his widow did not wish to pursue the project.[100]

Appearance and voice recordings

editUnlike the image of the classic magician, Houdini was short and stocky and typically appeared on stage in a long frock coat and tie. Most biographers give his height as 5 feet 5 inches (1.65 m), but descriptions vary. Houdini was also said to be slightly bow-legged, which aided in his ability to gain slack during his rope escapes. In the 1997 biography Houdini!!!: The Career of Ehrich Weiss, author Kenneth Silverman summarizes how reporters described Houdini's appearance during his early career:

They stressed his smallness – "somewhat undersized" – and angular, vivid features: "He is smooth-shaven with a keen, sharp-chinned, sharp-cheekboned face, bright blue eyes and thick, curly, black hair." Some sensed how much his complexly expressive smile was the outlet of his charismatic stage presence. It communicated to audiences at once warm amiability, pleasure in performing, and, more subtly, imperious self-assurance. Several reporters tried to capture the charming effect, describing him as "happy-looking", "pleasant-faced", "good natured at all times", "the young Hungarian magician with the pleasant smile and easy confidence".[101]

Houdini made the only known recordings of his voice on Edison wax cylinders on October 29, 1914, in Flatbush, New York. On them, Houdini practices several different introductory speeches for his famous Chinese Water Torture Cell. He also invites his sister, Gladys, to recite a poem. Houdini then recites the same poem in German. The six wax cylinders were discovered in the collection of magician John Mulholland after his death in 1970. They are part of the David Copperfield collection.[102]

Legal issues

editIn September 1900, Houdini was summoned by the German police prior to his first performance in the country who suspected his act was fake. Subsequently in Berlin, he was stripped naked and forced to perform an escape routine in front of 300 policemen. Houdini was tightly restrained with "thumbscrews, finger locks, and five different hand and elbow irons". He was able to escape in 6 minutes, and later used the stunt in advertising. Subsequently in 1901, a newspaper in Cologne accused him of attempting to bribe a police officer in order to rig an escape attempt, and paying a civilian police employee to aid him with another performance. Houdini sued the newspaper and the police officer for slander. As part of the trial, Houdini was asked to open without the aid of tools one of the police officer's handcrafted locks, for which the officer had said that Houdini had tried to bribe him. Houdini was able to do so, and won the case.[103]

Personal life

editHoudini became an active Freemason and was a member of St. Cecile Lodge No. 568 in New York City.[104]

In 1904, Houdini bought a New York City townhouse at 278 West 113th Street in Harlem. He paid US$25,000 (equivalent to $847,778 in 2023) for the five-level, 6,008-square-foot house, which was built in 1895, and lived in it with his wife Bess, and various other relatives until his death in 1926. In March 2018, it was purchased for $3.6 million. A plaque affixed to the building by the Historical Landmark Preservation Center reads, "The magician lived here from 1904 to 1926 collecting illusions, theatrical memorabilia, and books on psychic phenomena and magic."[105]

In 1919, Houdini moved to Los Angeles to film. He resided in 2435 Laurel Canyon Boulevard, a house of his friend and business associate Ralph M. Walker, who owned both sides of the street, 2335 and 2400, the latter address having a pool where Houdini practiced his water escapes. 2400 Laurel Canyon Boulevard, previously numbered 2398, is presently known as The Houdini Estate, thus named in the honor of Houdini's time there, the same estate where Bess Houdini threw a party for 500 magicians years after his death. After decades of abandonment, the estate was acquired in 2006 by José Luis Nazar, a Chilean/American citizen who has restored it to its former splendor.[71]

In 1918, he registered for selective service as Harry Handcuff Houdini.[106]

Death

editHoudini died on October 31, 1926 at the age of 52 from peritonitis (swelling of the abdomen), possibly related to appendicitis and possibly related to punches to his abdomen he had received about a week and a half earlier.

Witnesses to an incident at Houdini's dressing room in the Princess Theatre in Montreal on October 22, 1926, speculated that Houdini's death was caused by Jocelyn Gordon Whitehead (1895–1954), who repeatedly struck Houdini's abdomen.[107]

The accounts of the witnesses, students named Jacques Price and Sam Smilovitz (sometimes called Jack Price and Sam Smiley), generally corroborated each other. Price said that Whitehead asked Houdini "if he believed in the miracles of the Bible" and "whether it was true that punches in the stomach did not hurt him". Houdini offered a casual reply that his stomach could endure a lot. Whitehead then delivered "some very hammer-like blows below the belt". Houdini was reclining on a couch at the time, having broken his ankle while performing several days earlier. Price said that Houdini winced at each blow and stopped Whitehead suddenly in the midst of a punch, gesturing that he had had enough, and adding that he had had no opportunity to prepare himself against the blows, as he did not expect Whitehead to strike him so suddenly and forcefully. Had his ankle not been broken, he would have risen from the couch into a better position to brace himself.[107][108]

Throughout the evening, Houdini performed in great pain. He had insomnia and remained in constant pain for the next two days, but did not seek medical help. When he finally saw a doctor, he was found to have a fever of 102 °F (39 °C) and acute appendicitis, and was advised to have immediate surgery. He ignored the advice and decided to go on with the show.[109][110] When Houdini arrived at the Garrick Theater in Detroit, Michigan, on October 24, 1926, for what would be his last performance, he had a fever of 104 °F (40 °C). Despite the diagnosis, Houdini took the stage. He was reported to have passed out during the show, but was revived and continued. Afterwards, he was hospitalized at Detroit's Grace Hospital where he died from peritonitis on October 31, aged 52.[107]

It is unlikely that the dressing room incident caused Houdini's eventual death, since the effects of sustaining blunt trauma alongside appendicitis is debated in medical literature.[111][107] Although rare, acute appendicitis which follows after direct abdominal trauma has been observed.[112] One theory suggests that Houdini was unaware that he was suffering from appendicitis, and he might have taken his abdominal pain more seriously had he not coincidentally received blows to the abdomen.[107] According to Adam Begley, it is more likely that Houdini was suffering the effects of appendicitis prior to the punch, and his reluctance to seek medical care delayed potential treatment.[113][114]

After taking statements from Price and Smilovitz, Houdini's insurance company concluded that the death was due to the dressing-room incident and paid double indemnity.[109]

Houdini grave site

editHoudini's funeral was held on November 4, 1926, in New York, with more than 2,000 mourners in attendance.[115] He was interred in the Machpelah Cemetery in Glendale, Queens, with the crest of the Society of American Magicians inscribed on his grave site. A statuary bust was added to the exedra in 1927, a rarity, because graven images are forbidden in Jewish cemeteries. In 1975, the bust was destroyed by vandals. Temporary busts were placed at the grave until 2011 when a group from the Houdini Museum in Scranton, Pennsylvania, placed a permanent bust with the permission of Houdini's family and of the cemetery.[116]

The Society of American Magicians took responsibility for the upkeep of the site, as Houdini had willed a large sum of money to the organization he had grown from one club to 5,000–6,000 dues-paying membership worldwide. The payment of upkeep was abandoned by the society's dean George Schindler, who said "Houdini paid for perpetual care, but there's nobody at the cemetery to provide it", adding that the operator of the cemetery, David Jacobson, "sends us a bill for upkeep every year but we never pay it because he never provides any care." Members of the Society tidy the grave themselves.[117]

Machpelah Cemetery operator Jacobson said that they "never paid the cemetery for any restoration of the Houdini family plot in my tenure since 1988", claiming that the money came from the cemetery's dwindling funds. The granite monuments of Houdini's sister, Gladys, and brother, Leopold were also destroyed by vandals.[118] For many years, until recently, the Houdini grave site has been only cared for by Dorothy Dietrich and Dick Brookz of the Houdini Museum in Scranton, Pennsylvania.[119] The Society of American Magicians, at its National Council Meeting in Boca Raton, Florida, in 2013, under the prompting of Dietrich and Brookz, voted to assume the financial responsibilities for the care and maintenance of the Houdini Gravesite.[120] While the actual plot will remain under the control of Machpelah Cemetery management, the Society of American Magicians, with the help of the Houdini Museum in Pennsylvania, will be in charge of the restoration.[121]

Houdini's widow, Bess, died of a heart attack on February 11, 1943, aged 67, in Needles, California, while on a train en route from Los Angeles to New York City. She had expressed a wish to be buried next to her husband, but instead was interred 35 miles due north at the Gate of Heaven Cemetery in Westchester County, New York, as her Catholic family refused to allow her to be buried in a Jewish cemetery.[122]

Proposed exhumation

editOn March 22, 2007, Houdini's great-nephew (the grandson of his brother Theo) George Hardeen announced that the courts would be asked to allow exhumation of Houdini's body to investigate the possibility of Houdini being murdered by spiritualists, as suggested in the biography The Secret Life of Houdini.[123] In a statement given to the Houdini Museum in Scranton, the family of Bess Houdini opposed the application and suggested it was a publicity ploy for the book.[124] The Washington Post stated that the press conference was not arranged by the family of Houdini. Instead, the Post reported, it was orchestrated by the book's authors William Kalush and Larry Sloman, who had hired the public relations firm Dan Klores Communications to promote the book.[125]

In 2008, it was revealed the parties involved had not filed legal papers to perform an exhumation.[126]

Legacy

editHoudini's brother, Theodore Hardeen, who returned to performing after Houdini's death, inherited his brother's effects and props. Houdini's will stipulated that all the effects should be "burned and destroyed" upon Hardeen's death. Hardeen sold much of the collection to magician and Houdini enthusiast Sidney Hollis Radner during the 1940s, including the water torture cell.[127] Radner allowed choice pieces of the collection to be displayed at The Houdini Magical Hall of Fame in Niagara Falls, Ontario. In 1995, a fire destroyed the museum. The water torture cell's metal frame remained, and it was restored by illusion builder John Gaughan.[128] Many of the props contained in the museum such as the mirror handcuffs, Houdini's original packing crate, a milk can, and a straitjacket, survived the fire and were auctioned in 1999 and 2008.

Radner loaned the bulk of his collection for archiving to the Outagamie Museum in Appleton, Wisconsin, but reclaimed it in 2003 and auctioned it in Las Vegas, on October 30, 2004.[129]

Houdini was a "formidable collector", and bequeathed many of his holdings and paper archives on magic and spiritualism to the Library of Congress, which became the basis for the Houdini collection in cyberspace.[130] Houdini's book collecting has been explored in an essay in The Book Collector.[131]

In 1934, the bulk of Houdini's collection of American and British theatrical material, along with a significant portion of his business and personal papers, and some of his collections of other magicians were sold to pay off estate debts to theatre magnate Messmore Kendall. In 1958, Kendall donated his collection to the Hoblitzelle Theatre Library at the University of Texas at Austin.[132] In the 1960s, the Hoblitzelle Library became part of the Harry Ransom Center. The extensive Houdini collection includes a 1584 first edition of Reginald Scot's Discoverie of Witchcraft and David Garrick's travel diary to Paris from 1751.[133][134][non-primary source needed] Some of the scrapbooks in the Houdini collection have been digitized.[135] The collection was exclusively paper-based until April 2016, when the Ransom Center acquired one of Houdini's ball weights with chain and ankle cuff. In October 2016, in conjunction with the 90th anniversary of the death of Houdini, the Ransom Center embarked on a major re-cataloging of the Houdini collection to make it more visible and accessible to researchers.[136] The collection reopened in 2018, with its finding aids posted online.[137]

A large portion of Houdini's estate holdings and memorabilia was willed to his fellow magician and friend John Mulholland (1898–1970). In 1991, illusionist and television performer David Copperfield purchased all of Mulholland's Houdini holdings from Mulholland's estate. These are now archived and preserved in Copperfield's warehouse at his headquarters in Las Vegas. It contains the world's largest collection of Houdini memorabilia and preserves approximately 80,000 items of memorabilia of Houdini and other magicians, including Houdini's stage props and material, his rebuilt water torture cabinet and his metamorphosis trunk. It is not open to the public, but tours are available by invitation to magicians, scholars, researchers, journalists and serious collectors.[citation needed]

In a posthumous ceremony on October 31, 1975, Houdini was given a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 7001 Hollywood Blvd.[138]

The Houdini Museum in Scranton, Pennsylvania, bills itself as "the only building in the world entirely dedicated to Houdini". It is open to the public year-round by reservation. It includes Houdini films, a guided tour about Houdini's life and a stage magic show. Magicians Dorothy Dietrich and Dick Brookz opened the facility in 1991.[139] The House of Houdini is a museum and performance venue located at 11, Dísz square in the Buda Castle in Budapest, Hungary. It claims to house the largest collection of original Houdini artifacts in Europe.[140] The Houdini Museum of New York is located at Fantasma Magic, a retail magic manufacturer and seller located in Manhattan. The museum contains several hundred pieces of ephemera, most of which belonged to Harry Houdini.[citation needed]

In popular culture

edit- Houdini appeared as himself in Weird Tales magazine in three ghostwritten fictionalizations of sensational events from his career (issues of March, April, and May–June–July 1924). The third story, "Imprisoned with the Pharaohs," was written by horror writer H. P. Lovecraft based on Houdini's notes. The Houdini-Lovecraft collaboration was envisioned to continue, but the magazine ceased publication for financial reasons. When it resumed later in 1924, Houdini no longer figured in its plans.[141]

- Houdini (1953) – played by Tony Curtis

- Man of Magic – a 1966 musical about Houdini's life, produced by Harold Fielding. Stuart Damon played the title role in the show, which opened at the Opera House in Manchester on 22 October 1966[142] before transferring to the Piccadilly Theatre in London where it opened on 15 November and ran for 135 performances. Music was by Wilfred Josephs, under the pseudonym Wilfred Wylam.[143][144]

- The Great Houdini a.k.a. The Great Houdinis (1976) – played by Paul Michael Glaser (TV movie)

- A Magician Amongst the Spirits, a 1982 BBC radio drama about Houdini's life written by Bert Coules[145]

- "Houdini" (1982) – sung by Kate Bush (Song), a song which explores Bess Houdini attempting to contact Houdini after his death using the secret code they formed together for this purpose.[146]

- "Young Harry Houdini" (1987) – A highly fictionalized portrayal of Houdini during his childhood, portrayed by Wil Wheaton, as part of The Disney Sunday Movie series.

- FairyTale: A True Story (1997) – played by Harvey Keitel, a film about the Cottingley Fairies hoax.

- Houdini (1998) – played by Jonathon Schaech (TV Movie)

- Houdini (2014) – played by Adrien Brody (TV miniseries)[147]

- Michael Weston played Harry Houdini in the short-lived 2016 TV series Houdini & Doyle[148]

- The Ministry of Time—Episode 6, Season 2, Tiempo de magia (2016), played by Gary Piquer

- Doctor Who – Harry Houdini's War (2019) – played by John Schwab (Big Finish audio play)[149]

- d'ILLUSION: The Houdini Musical – The Audio Theater Experience (2020) – played by Julian R. Decker (Album musical/audiobook)[150][151][152]

- The straitjacket escape is used in the Warner Bros show, Batman: The Animated Series -- specifically in S1:E54 "Zatanna" -- as a training exercise for a young Bruce Wayne. In the episode "Be a Clown", S1:E9, it is combined with the water chest escape as a trap for Batman, set by the Joker.

Publications

editHoudini published numerous books during his career (some of which were written by his good friend Walter B. Gibson, the creator of The Shadow)[153]

- The Right Way to Do Wrong: An Exposé of Successful Criminals (1906)

- Handcuff Secrets (1907)

- The Unmasking of Robert-Houdin (1908), a debunking study of Robert-Houdin's alleged abilities.

- Magical Rope Ties and Escapes (1920)

- Miracle Mongers and Their Methods (1920)

- Houdini's Paper Magic (1921)

- A Magician Among the Spirits (1924)

- Houdini Exposes the Tricks Used by the Boston Medium "Margery" (1924)

- Imprisoned with the Pharaohs (1924), a short story ghostwritten by H. P. Lovecraft.

- How I Unmask the Spirit Fakers[permanent dead link], article for Popular Science (November 1925)

- How I do My "Spirit Tricks"[permanent dead link], article for Popular Science (December 1925)

- Conjuring (1926), article for the Encyclopædia Britannica's 13th edition.

Filmography

edit- Merveilleux Exploits du Célébre Houdini à Paris – Cinema Lux (1909) – playing himself

- The Master Mystery – Octagon Films (1918) – playing Quentin Locke

- The Grim Game – Famous Players–Lasky/Paramount Pictures (1919) – playing Harvey Handford

- Terror Island – Famous Players Lasky/Paramount (1920) – playing Harry Harper

- The Man from Beyond – Houdini Picture Corporation (1922) – playing Howard Hillary

- Haldane of the Secret Service – Houdini Picture Corporation/FBO (1923) – playing Heath Haldane

Posters

editSee also

editReferences

edit- ^ Schiller, Gerald. (2010). It Happened in Hollywood: Remarkable Events That Shaped History. Globe Pequot Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0762754496

- ^ "Harry Houdini". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ Houdini!, retrieved March 11, 2021

- ^ Maksel, Rebecca. "The Hunt for Houdini's Airplane". Air & Space Magazine. Retrieved August 4, 2021.

- ^ "137 years ago in Budapest..." Wild About Harry. Retrieved March 24, 2011.

- ^ "Harry Houdini | Biography & Facts". www.britannica.com. Retrieved December 11, 2021.

- ^ "Hardeen Dead, 69. Houdini's Brother. Illusionist, Escape Artist, a Founder of Magician's Guild. Gave Last Show May 29". The New York Times. June 13, 1945. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

Theodore Hardeen, a brother of the late Harry Houdini, illusionist and a prominent magician in his own right, died yesterday in the Doctors Hospital. His age was 69.

- ^ Meyer, Bernard C. (1976), Houdini: A Mind in Chains, E.P. Dutton & Co., Chapter 1, p. 5, ISBN 0841504482.

- ^ "The mystery of Carrie Gladys Weiss". Wild About Harry. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ US National Archives Microfilm serial: M237; Microfilm roll: 413; Line: 38; List number: 684.

- ^ 1880 US Census with Samuel M. Weiss, Cecelia (wife), Armin M., Nathan J., Ehrich, Theodore, and Leopold.

- ^ Houdini's Forgotten Years The Houdini File.

- ^ "Harry Houdini" (PDF). American Decades. December 16, 1998. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 9, 2016. Retrieved February 4, 2016. Also at Biography In Context.

- ^ Loxton, Daniel (January 30, 2013). "The Remarkable Mr. Rinn". Skeptic Magazine. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- ^ Rocha, Guy. "MYTH No. 56 – No Disappearing Act for Harry Houdini at Piper's Opera House". Nevada State Library and Archives. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved March 24, 2011.

- ^ Immerso, Michael. (2002). Coney Island: The People's Playground. Rutgers University Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-0813531380

- ^ "Harry Houdini: Famous magician, master of escapes, Houdini metamorphosis". Houdini Magic. Archived from the original on May 5, 2023. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ Houdini, King of Cards The Houdini Files.

- ^ Johnson, Karl (2005). The Magician and the Cardsharp.

- ^ a b c d e Randi, James (1992). Conjuring. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-08634-2. OCLC 26162991.

- ^ Gresham, William Lindsay. (1959). Houdini: The Man Who Walked Through Walls. Holt. pp. 82–83

- ^ Price, David. (1985). Magic: A Pictorial History of Conjurers in the Theater. Cornwall Books. p. 191. ISBN 0845347381

- ^ Tait, Derek. (2017). The Great Houdini: His British Tours (Kindle Edition). Pen & Sword Books Ltd. Chapter One ISBN 978-1473867949

- ^ Silverman, p. 81.

- ^ Silverman, p. 109.

- ^ a b Steinmeyer, Jim. (2004). Hiding The Elephant: How Magicians Invented the Impossible. Da Capo Press. pp. 152–153. ISBN 0786714018

- ^ Jones, Graham Matthew. (2007). Trades of the Trick: Conjuring Culture in Modern France. New York University. pp. 96–98

- ^ Gresham, William Lindsay (1959). Houdini: The Man Who Walked Through Walls. Holt. p. 136

- ^ Steinmeyer, Jim. (2006). The Glorious Deception: The Double Life of William Robinson, Aka Chung Ling Soo, the Marvelous Chinese Conjurer. Da Capo Press. p. 291. ISBN 078671770X

- ^ Cannell, J. C. (1973). The Secrets of Houdini. New York: Dover Publications. pp. 36–41. ISBN 978-0486229133. Retrieved August 17, 2012.

- ^ "Houdini's escapes and magic – Houdini's unique challenges in Scranton, PA. during the vaudeville era". Archived from the original on August 20, 2013. Retrieved September 29, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kalush, William; Sloman, Larry (2006). The Secret Life of Houdini: The Making of America's First Superhero. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0743272070. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- ^ Steinmeyer, Jim. (2004). Hiding The Elephant: How Magicians Invented the Impossible. Da Capo Press. pp. 154–155. ISBN 0786714018 "He decided to portray Robert-Houdin as a liar and thief who was completely incompetent as a magician. Houdini had developed a hatred for his spiritual father. In 1908 his collection of articles was gathered together, expanded and sold to a London publisher. By comparing the original articles with the finished book, it's clear that Houdini employed a ghost writer to polish the language and clarify his points. Other surviving manuscripts from Houdini demonstrate that most of Houdini's writing depended on ghostwriters. The theme of his book on Robert-Houdin was sharpened to a razor's edge, and was now titled The Unmasking of Robert-Houdin."

- ^ Goto-Jones, Chris. (2016). Conjuring Asia. Cambridge University Press. p. 193. ISBN 978-1107076594

- ^ Inge, M. Thomas; Hall, Dennis. (2002). The Greenwood Guide to American Popular Culture, Volume 3. Greenwood Press. p. 1037. ISBN 978-0313323690 "Stung by the refusal of the widow of Robert-Houdin's son Emile to receive him in 1901, Houdini launched a literary vendetta against his former hero in the form of a book, The Unmasking of Robert-Houdin, published seven years later. While the book did not achieve its aim, it remains of considerable historical interest as the first sustained attempt to mine Houdini's large and growing collection for historical information. Its errors and oversights became the subject of two extensive rebuttals. The first was Maurice Sardina's Les Erreurs de Harry Houdini, translated and edited by Victor Farelli as Where Houdini Was Wrong. The second was Jean Hugard's Houdini's "Unmasking": Fact vs Fiction.

- ^ Steinmeyer, Jim. (2004). Hiding The Elephant: How Magicians Invented the Impossible. Da Capo Press. p. 156. ISBN 0786714018 "A number of researchers and authors have dismissed his claims and defended Robert-Houdin's reputation."

- ^ Jones, Graham M. (2011). Trade of the Tricks: Inside the Magician's Craft. University of California Press. p. 208. ISBN 978-0520270466 "The publication ultimately did more to tarnish Houdini's reputation than to refute Robert-Houdin's claims to originality and distinction especially in France, where magicians rallied to defend their spiritual progenitor against aspersions cast by an American parvenu."

- ^ "1912 Harry Houdini 'Water Torture Cell' Presentation Piece from Circus Busch Containing the Original Concept Art for the Performance's Famous Poster". Archived from the original on December 20, 2007. Retrieved May 6, 2008.

- ^ "The Vanishing Elephant". Retrieved June 30, 2016.

- ^ Christopher, Milbourne. (1990 edition, originally published in 1962). Magic: A Picture History. Dover Publications. p. 160. ISBN 0486263738 "Morritt invented a 'Disappearing Donkey'. When he expanded the idea so that an elephant could be whisked away in a box, Houdini bought the full rights to the spectacular illusion."

- ^ Silverman, p. 224.

- ^ Silverman, Kenneth (1996). Houdini! The Career of Ehrich Weiss: American Self-Liberator, Europe's Eclipsing Sensation, World's Handcuff King & Prison Breaker. HarperCollins. p. 544. ISBN 978-0060169787.

- ^ John Cox (2017) [2011]. "Houdini: A Biography". Wild About Harry. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ Copperfield, David; Wiseman, Richard; Britland, David (2021). David Copperfield's history of magic. New York, NY. ISBN 978-1-9821-1291-2. OCLC 1236259508.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ The Secret Life of Houdini, Kaulush & Sloman, 2006.

- ^ "Houdini's Great Victory". Daily Illustrated Mirror. March 18, 1904.

- ^ Silverman, pp. 59–62.

- ^ "Keys To Houdini's Secrets". Mysteries at the Museum. Travel Channel. November 23, 2010. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- ^ "Mirror Cuffs". Genii Magazine. Retrieved November 30, 2011.

- ^ "Travel Channel Dorothy Dietrich Promo Houdini Mirror Cuffs". Mysteries at the Museum. Travel Channel. November 2, 2011. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved November 29, 2011.

- ^ Hanzlik, Mick (March 16, 2013). "The Replica Mirror Cuffs". Wild About Harry.

- ^ a b Randi, James; Sugar, Bert Randolph (1976). Houdini, his life and art. New York: Grosset & Dunlap. ISBN 978-0-448-12546-6.

- ^ Christopher, Milbourne (1976). Houdini: A Pictorial Life. Ty Crowell Co. p. 54. ISBN 978-0690011524.

- ^ "American Museum of Magic". Marshall area Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007. Retrieved April 20, 2008.

- ^ Tait, Derek (2018). The Great Illusionists. Barnsley South, Yorkshire: Pen and Sword History. pp. 260–274. ISBN 978-1473890763.

- ^ "Thousands see Harry Houdini escape from a straitjacket while hanging in mid-air, Chicago, Ill.", International news [1923 or 1924?]

- ^ Henning, Doug (1977). Houdini His Legend and His Magic. Times Books. ISBN 978-0812906868.

- ^ Christopher, Milbourne (1969). Houdini: The Untold Story. Ty Crowell Co. p. 140. ISBN 978-0891909811.

- ^ "Digging into Houdini's Buried Alive". Retrieved January 6, 2011.

- ^ Silverman, pp. 397–403.

- ^ "Uncovering Houdini's second underwater test". Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ Silverman, p. 406.

- ^ "Houdini Defeats Hackenschmidt and other revelations from Disappearing Tricks". Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- ^ Disappearing Tricks by Matthew Solomon, 2010, p. 95.

- ^ Silverman, p. 205.

- ^ Stedman, Eric (2010). The Mysteries of Myra. p. 8.

- ^ "Adroit Harry and ancient hokum". Retrieved December 30, 2012.

- ^ "Turner Classic Movies to Host World Premiere Screening of Long Lost Harry Houdini Classic The Grim Game at 2015 TCM Classic Film Festival" (Press release). TCM. January 23, 2015. Archived from the original on January 2, 2016. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- ^ "Houdini Museum in Scranton PA Reveals the Secrets of Uncovering Houdini's 1919 Lost Silent Film The Grim Game". Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved January 23, 2015.

- ^ Silverman, pp. 226–249.

- ^ a b "The true story of the Laurel Canyon Houdini Estate". John Cox and Patrick Culliton. Retrieved March 30, 2012.

- ^ "The true story of the Laurel Canyon Houdini Estate". Patrick Culliton and John Cox. Retrieved March 30, 2012.

- ^ "Houdini The Movie Star DVD collection released". Retrieved April 8, 2008.

- ^ José Sanchez Besa. "The First Air Races". www.thefirstairraces.net.

- ^ Emilio Edwards. "The First Air Races". www.thefirstairraces.net.

- ^ Fledgling Aviators: Trying Their Wings: Houdini and Banks, The Argus, (Wednesday, March 16, 1910), p. 13.

- ^ Houdini as Flyer, The (Sydney) Sunday Times, (Sunday, February 6, 1910), p. 2.

- ^ "Table Talk (Melbourne, Vic. : 1885–1939) 3 Mar 1910". Trove. p. 25.

- ^ For photographs taken of Houdini's preparation at Diggers Rest before his first flight see: Houdini's Experiment with his Voisin Bi-Plane at Diggers' Rest, The Australasian, (Saturday, 19 March 1910), p. 35.

- ^ Learning to Fly: Experiments in Victoria, The Sydney Morning Herald, (Thursday, 17 March 1910), p. 6.

- ^ First Air Flight in Australia – Houdini at Diggers' Rest, The Leader, (Saturday, 26 March 1910), p. 25.

- ^ The Airship in Victoria: Houdini’s Flights at Digger’s Rest, The Weekly Times’, (Saturday, 2 April 1910), p. 28.

- ^ Houdini Flies: Trials at Digger’s Rest: Three Successful Flights: Height of 100 ft. Reached, The Argus, (Saturday, 19 March 1910), p. 18.

- ^ Only one of those who signed the 18 March 1910 certificate, Robert Howie, a local farmer, was unconnected with either Houdini or Ralph Coningsby Banks (1883–1955), a Melbourne-based aviator, whose Wright Flyer was also stationed on the same paddock, right next to Houdini's base.

- ^ In Full Flight: Houdin’s Success: Three and a Half Miles, The Argus, Monday, 21 March 1910), p. 9.

- ^ "Australian Flights". Argus. March 22, 1910 – via Trove.

- ^ When Australia first saw Planes fly: Houdini's 1910 Voisin Biplane was Closely Followed by an Australian-built Machine, The Argus Week-end Magazine, (Saturday, 3 December 1938), p. 3: obviously, the mistaken signature of "James. L. Watson" should have been read as "James. I. Watson".

- ^ Silverman, pp. 137–154.

- ^ "Notes to Houdini and the ghost of Abraham Lincoln". Library of Congress. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- ^ Jay, Ricky (March 3, 2011). "Conjuring". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- ^ ""Margery" the Medium Exposed". American Experience. PBS. 2011. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- ^ Nickell, Joe (2007). Adventures in Paranormal Investigation. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 213–215. ISBN 978-0813124674

- ^ Polidoro, Massimo. (2001). Final Séance: The Strange Friendship Between Houdini and Conan Doyle. Prometheus Books. pp. 127–128. ISBN 1573928968

- ^ a b Williams, Michael (October 29, 2014). "Annual Houdini Séance to be held on Halloween". Tennessee Star Journal. Archived from the original on October 22, 2015. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- ^ see Conan Doyle's The Edge of The Unknown, published in 1931.

- ^ Spragget, Allen; Rauscher, William V. (1974). Arthur Ford: The Man Who Talked with the Dead. New American Library. p. 246.

- ^ Berthiaume, Ed (October 31, 2014). "Boldt CEO spends Halloween in search of Houdini". The Post-Crescent. Appleton, Wisconsin. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- ^ Houdini Facts [1].

- ^ "Houdini's Halloween". WGN-TV and Red Eye. October 28, 2005. Archived from the original on March 10, 2007. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ Joshi, S.T., ed. (2005). Collected Essays of H. P. Lovecraft: Science. Vol. 3. New York: Hippocampus Press. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-0974878980.

- ^ Silverman, p. 31.

- ^ "Houdini speaks in 1970". Retrieved November 13, 2010.

- ^ "The German Slander Trial (1902)". www.pbs.org. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ "Famous Masons". MWGLNY. January 2014. Archived from the original on November 10, 2013.

- ^ Gordon, Lisa Kaplan (March 27, 2018). "Harry Houdini's House Is About to Disappear from the Market". Town & Country. Archived from the original on October 30, 2019. Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- ^ "Notable Registrants of the World War I Draft: Harry Houdini". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Mikkelson, Barbara and David P. (September 2, 2014). "Punched Out". Snopes.com.

- ^ Conan Doyle, Arthur (1930). Edge of the Unknown. Lulu.com. ISBN 978-1409235149.

- ^ a b Bell, Don (2005). The Man Who Killed Houdini. Véhicule Press. ISBN 978-1550651874.

- ^ Benoit, Tod (May 2003). Where Are They Buried? How Did They Die?. Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers. p. 469. ISBN 978-0739465585.

- ^ Naumann, David N; Barker, Tom (March 15, 2023). "Traumatic appendicitis is probably not real: an illustrative analysis of coincidental occurrences in nature". Trauma Surgery & Acute Care Open. 8 (1): e001093. doi:10.1136/tsaco-2023-001093. ISSN 2397-5776. PMC 10030918. PMID 36967864.

- ^ Toumi, Zaher; Chan, Anthony; Hadfield, Matthew B; Hulton, Neil R (September 2010). "Systematic review of blunt abdominal trauma as a cause of acute appendicitis". The Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 92 (6): 477–482. doi:10.1308/003588410X12664192075936. ISSN 0035-8843. PMC 3182788. PMID 20513274.

- ^ Begley, Adam (2020). Houdini: The Elusive American. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 173–183. ISBN 9780300230796.

- ^ Begley, Adam (March 11, 2020). "Did Houdini Really Die after Being Sucker Punched?". Yale University Press. Archived from the original on January 13, 2024. Retrieved September 29, 2024.

- ^ Goldenberg, Suzanne (March 24, 2007). "Final Escape for the Master of Illusion? Houdini's Family Press for Exhumation". The Guardian. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (October 24, 2011). "Houdini Returns". The New York Times. Retrieved October 24, 2011.

- ^ Kilgannon, Corey (October 31, 2008). "Houdini's Final Trick, a Tidy Grave". The New York Times. Retrieved October 31, 2008.

- ^ LeDuff, Charlie (November 24, 1996). "Houdinis' Plot Is Cleared Up, and Then Thickens". The New York Times. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

- ^ Sanders, Dal (December 15, 2013). "From the President's Desk Dal Sanders" (PDF). MUM Magazine. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 5, 2014. Retrieved December 15, 2013.

- ^ Barca, Christopher (October 9, 2014). "Houdini's grave to get a facelift". Queens Chronicle. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ Rosenberg, Eli (October 27, 2014). "Houdini's gravesite to get a magic fix in Queens". Daily News. New York. Retrieved October 27, 2014.

- ^ "Bess Houdini dies in 1943". Houdini.net. Archived from the original on November 5, 2015. Retrieved April 1, 2011.

- ^ "Grandnephew seeks to 'set record straight' about Houdini's death". CBC News. March 23, 2007. Retrieved March 23, 2007.

- ^ "Family Statement re: exhumation". Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved March 26, 2007.

- ^ Segal, David (March 24, 2007). "Why Not Just Hold a Seance?". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 24, 2007.

- ^ "Time to bury the Houdini exhumation". Wild About Harry. Retrieved April 9, 2011.

- ^ "With Sadness, Prime Houdini Artifact Collector Puts Items on Auction Block". The New York Times. October 29, 2004. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

... Mr. Radner, aka Rendar the Magician, owns one of the world's biggest and most valuable collections of Harry Houdini artifacts, including the Chinese Water Torture Cell, one of Houdini's signature props from 1912 until his death in 1926. Most of the items were given to Mr. Radner in the 1940s by Houdini's brother, Theodore Hardeen. Hardeen considered Radner, then a student at Yale with a reputation for jumping from diving boards in handcuffs, as his protégé. Until early this year, the collection was on display at the Outagamie Museum in Appleton, Wisconsin, where Houdini's father was the town rabbi in the 1870s. But after a rancorous falling out between Mr. Radner and museum officials, the 1,000-piece collection was packed-up and shipped here, where it will be auctioned on Saturday in the windowless back room at the Liberace Museum and on eBay.

- ^ "The Mystery of the Two Torture Cells". Wild About Harry. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ^ "Houdini's Magic Shop | Novelties". houdini.com. Archived from the original on May 15, 2006. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ Higbee, Joan. "Great Escapes". American Memory Web Site, Hosts Houdini Collection. Library of Congress. Retrieved March 24, 2011.

- ^ Downs, Troy, “Harry Houdini’s Library, The Book Collector 69 (Summer, 2020); 251–265.

- ^ "The Performing Arts Collection". hrc.utexas.edu. Archived from the original on March 15, 2017. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

- ^ Scot, Reginald (January 1, 1584). The discouerie of witchcraft,: wherein the lewde dealings of witches and witchmongers is notablie detected, the knauerie of coniurors, the impietie of inchantors, thefollie of soothsaiers, the impudent falshood of cousenors, the infidelitie of atheists, the pestilent practices of Pythonists, the curiositie of figure casters, the vanitie of dreamers, the beggerlie art of alcumystrie, the abhomination of idolatrie, the horrible art of poisoning, the vertue and power of naturall magike, and all the conueiances of legierdemaine and iuggling are deciphered and many other things opened which have long lien hidden, howbeit verie necessarie to be knowne. Heerevnto is added a treatise vpon the nature and substance of spirits and diuels, &c. Imprinted at London: By William Brome.

- ^ "Harry Ransom Center on Twitter". Twitter. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

- ^ "Harry Houdini Scrapbook Collection". hrc.contentdm.oclc.org. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

- ^ "Houdini: Illusionist and collector". Cultural Compass. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

- ^ "Harry Houdini: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center". norman.hrc.utexas.edu. Evanion, Henry, 1831?–1905., Hardeen, 1876–1945., Houdini, Beatrice, 1876–1943., Houdini, Harry, 1974–1926., Ingersoll, Robert Green, 1833–1899., Northcote, James, 1746–1831. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Harry Houdini". Hollywood Walk of Fame. Hollywood Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved May 13, 2015.

Address: 7001 Hollywood Blvd. Ceremony: October 31, 1975.

- ^ "Ten Offbeat Reasons To Make Scranton, PA Your Next Mini-Escape". HuffPost. April 20, 2015. Retrieved June 18, 2024.

- ^ "House of Houdini Official website". The House of Houdini. Retrieved January 22, 2017.

- ^ "The Magician's Ghostwriters" in The Thing's Incredible! The Secret Origins of Weird Tales (Off-Trail Publications, 2018).

- ^ Man of Magic: theatre poster, Manchester Opera House 22 Oct 1966

- ^ "Production of Man of Magic". Theatricalia.

- ^ "Man of Magic". Stage Door Records.

- ^ "Saturday-Night Theatre: A Magician Amongst the Spirits". The Radio Times (3072). BBC: 31. September 23, 1982. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- ^ "Houdini - Kate Bush Encyclopedia". August 16, 2017.

- ^ "It's On! History greenlights Houdini miniseries". Wild About Harry. Retrieved August 19, 2013.

- ^ "Houdini and Doyle". IMDb.

- ^ "255. Doctor Who: Harry Houdini's War – Doctor Who – The Monthly Adventures – Big Finish". www.bigfinish.com.

- ^ "d'ILLUSION: The Houdini Musical – The Aduio Theater Experience". Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- ^ "d'ILLUSION: The Houdini Musical Announces Launch of Audiobook". Broadway World.

- ^ "d'ILLUSION: The Houdini Musical Releases Theater Audio Experience". Broadway World.

- ^ "James Randi's Swift". randi.org. July 14, 2006.

Bibliography

edit- Brandon, Ruth (1993). The Life and Many Deaths of Harry Houdini. London: Secker & Warburg, Ltd. ISBN 978-0394224152.

- Fleischman, Sid (2006). Escape! The Story of The Great Houdini. Greenwillow Books. ISBN 978-0060850944.

- Gresham, William Lindsay Houdini: The Man Who Walked Through Walls (New York: Henry Holt & Co., 1959).

- Henning, Doug with Charles Reynolds. Houdini: His Legend and His Magic (New York: Times Books, 1978). ISBN 978-0446873284.

- Kalush, William; Sloman, Larry (2006). The Secret Life of Houdini: The Making of America's First Superhero. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0743272070.

- Kellock, Harold. Houdini: His Life-Story from the recollections and documents of Beatrice Houdini, (Harcourt, Brace Co., June 1928).

- Kendall, Lance. Houdini: Master of Escape (New York: Macrae Smith & Co., 1960). ISBN 006092862X.

- Meyer, M.D., Bernard C. Houdini: A Mind in Chains (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1976). ISBN 0841504482.

- Randi, James; Sugar, Bert Randolph (1976). Houdini, his life and art. New York: Grosset & Dunlap. ISBN 978-0-448-12546-6.