The House of Loreius Tiburtinus (more correctly the House of Octavius Quartio after its true owner) is renowned for well-preserved art, mainly in wall-paintings as well as its large gardens.[1]

| House of Octavius Quartio | |

|---|---|

Casa di Ottavio Quartione | |

Summer biclinium of the House of D. Octavius Quartio | |

| |

| General information | |

| Status | archaeological remains |

| Architectural style | Roman fauces-atrium-tablinum matrix |

| Classification | Townhouse |

| Location | Pompeii, Roman Empire |

| Address | II, 2, 2, Via dell'Abbondanza, Pompei, Italy |

| Town or city | Pompei |

| Country | Italy |

| Coordinates | 40°45′06″N 14°29′33″E / 40.7517°N 14.4924°E |

| Current tenants | 0 |

| Named for | Bronze seal of D. Octavius Quartio found in a cubiculum with stove for firing terracotta pots |

| Renovated | 62 |

| Destroyed | 79 |

| Known for | Summer biclinium with frescoes depicting Narcissus and the myth of Pyramus and Thisbe as well as a triclinium decorated with scenes from the Illiad and two perpendicular euripi in the expansive garden |

| Other information | |

| Number of rooms | 18 (ground floor only) |

It is in the Roman city of Pompeii and with the rest of Pompeii was preserved by the volcanic eruption of Mount Vesuvius in or after October 79 AD.

Location

editIts Pompeian street address is II, 2, 2-5 and it is located on the Via dell'Abbondanza (or street of abundance), one of the most prosperous streets in Pompeii, and conveniently situated for both the palaestra and the amphitheatre. The section of Via dell'Abbondanza it occupied was closed off to cart traffic in ancient times.[2][3]

Name

editThe naming of this house[4] was wrongly derived from electoral graffiti etched in the outer façade, some saying "Vote for Loreius" and others "Vote for Tiburtinus." In fact, the last known owner of the house was a man named Octavius Quartio, whose bronze seal was found inside the house during excavation.[2] Some historians choose to refer to this house as the House of Octavius Quartio.

Excavation

editThe House of Loreius Tiburtinus (Octavius Quartio) was discovered and excavated between the years 1916 and 1921 by Vittorio Spinazzola, Pompeii superintendent between 1911-1923. Further archaeological campaigns were conducted in 1933 and 1935 under the supervision of Amedeo Maiuri. The last excavation in 1971 was supervised by Alfonso De Francisci.[5]

History

editThe two original structures combined to form this palatial residence were originally built during the Samnite Period [5] around the 3rd century BCE.[6] The domus covered an entire insula before the earthquake of 62 AD and had two atriums and two entrances. After the earthquake, part of the house (II 2, 4) was sold to another owner and was made independent. It is thought the arcaded terrace (loggia) and the large garden were completed at this time as well[5] extending the area to about 1,800 square meters.[6] Art historian John R. Clarke has suggested the expanded garden space may have been used for commercial purposes, "like that of its neighbor two blocks to the east, the Praedia of Julia Felix, citing Wilhelmina Jashemski.[7]

Layout and Decoration

editThe exterior walls of the complex are composed of opus incertum (stone rubble embedded in concrete) with ashlar piers, except for the easternmost corner, which was constructed with opus vittatum mixtum (a combination of brick and stone blocks).[8] The main entrance, is flanked by two shops, the Caupona of Astylus and Pardalus (II 2,1), with remains of a food serving counter and stairs to an upper floor, and the Caupona of Athictus. This shop had only a sales counter of wood that left an imprint below the plastered east wall.[9] It is thought these shop spaces were once part of the house but were eventually separated from the main structure and either rented or sold [4] as both shops had doorways to the atrium of the main House at II 2,2. The Athictus shop also had a doorway leading into Room 3 (blue).[9]

The inside of the house is fairly uniform in its organization, and matches the standard of much of the Roman architecture at the time. Unfortunately some of the house's original integrity was compromised before the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in the earthquake of 62 AD[4] and Allied bombing raids in 1943 during WWII.

The fauces (entrance) at II 2,2 opens into a rectangular atrium with an impluvium in the center. This basin collected rainwater through a hole in the roof to be used by the patrons of the house.[4] It was later repurposed into a fountain surrounded by a bed of plants. This portion of the residence suffered extensive damage from exposure to the elements after its excavation in 1916 as well as Allied bomb damage in 1943. At the rear of the atrium, the home's tablinum (g) has been replaced with a small columned pseudo-peristyle. The columns are painted red at the base and white above. Though faded, the walls still bear evidence of painting in the Fourth style with black panels separated by yellow columns above a red dado. On the east wall is the extremely faded remains of a panel painting but it's so damaged the subject can no longer be perceived.[9]

Patronage relationships began to evolve during the late Republic. More and more patronage extended over entire communities whether on the basis of political decree, benefaction by an individual who becomes the communities' patron, or by the community formally adopting a patron.[10] This may account for the elimination of a formal tablinum.

A number of the rooms adjoining the atrium are also in poor repair:

Room 3 (blue) has only a small piece of stucco left of its decoration. It contains what Spinazzola described as a kiln (muffola) for the baking and glazing of small vases/pots. It is in this room that the seal ring of D. Octavius Quartio was found.

Room 4 (blue), partially destroyed in the 1943 bombing, retains no decoration at all. It is thought to have been a triclinium. Likewise, all that remains of Room 5 (blue) are bare walls. It's doorway to what is thought to be a latrine 6 (blue) is still extant, though. Room 7 (blue), also without decoration, is accessed through Room 5 (blue).

Room "a", with a yellow middle zone with black dado, once contained a panel painting of Europa and the Bull, two medallions with one particularly fine portrait thought to be the owner's daughter, and painted imitation windows as documented by a 1930 photograph. These were all destroyed by concussion in one of the 1943 bombing raids.

Ala "b", a relatively large room decorated in the Fourth Style with red panels on a dark blue ground with floating soldier figures, survived, though it has faded severely from exposure.

Room "c", thought to have been another triclinium with yellow panels bordered in red was also damaged and faded due to exposure after excavation.

A small oecus "d" also decorated in the Fourth Style depicting architectural structures and landscapes in roundels on a white ground has survived. Room "e" has managed to retain fragments of its black and white floor mosaics and a panel picture of a hunting scene framed with garlands on a yellow ground.[9] These two rooms are thought to have been painted by a workshop located on the Via di Castricio.[5]

Room "f" on the west side of the pseudo-peristyle is an oecus decorated in the Fourth Style with white ground panels bordered in cinnabar red above a black dado with Egyptian and cultic motifs. Among figures portrayed include Bacchus with his thyrsus and a priest of Isis with a sistrum,[9] possibly depicting the owner.[5] Beneath it is the inscription "Amisusius Loreius Tiburtinus." This is in addition to the election slogans referring to Tiburtinus found on the outer facade of the house.

A biga (two-horse chariot) tops one of the painted architectural structures. There are also roundels depicting maenads and satyrs. Paintings of Diana bathing to the south and Actaeon attacked by his hunting dogs to the north suggest the room was used as a sacellum to scholars conducting the damage diagnosis of the site for the Piano della Conoscenza-Grande Progetto Pompei Project in 2016. Finnish scholar, Ilkka Kuivalainen, agrees, stating the presence of Bacchus clearly indicates cultic purposes. But, site curators do not think the room was used for religious purposes. They state on site signage:

"What at first sight appear to be stringent references to the goddess Isis and her cult are none other than proof of the exotic taste, a completely secular one, with an exclusively ornamental nature, which characterized the new ruling class that was being formed in the early decades of the empire."[9]

This room was also bomb damaged then partially restored from stucco fragments. The paintings have been attributed to the Vetii workshop.[5]

Room "h", a spacious triclinium, still retains much of its frescoes, although fragmentary. Two panels of images are painted continuously around the room. The more narrow lower panel depicts scenes of Achilles and the Iliad interspersed with simulated marble panels including Thetis giving weapons forged by Hephaestus to Achilles, Patroclus, dressed in the armor of Achilles, fighting from a wheeled vehicle, the funeral of Patroclus, a boxing match as part of the games held in honor of Patroclus, and Automedon readying the chariot for Achilles. At the far east end, is the iconic scene of Achilles dragging Hector's body behind his chariot followed by images of Priam led by Hermes taking a wagon out of Troy and entering the Greek camp and a kneeling King Priam pleading with Achilles for the body of Hector.

The wider upper panel portrays scenes from the myth of Heracles involving Telamon and Laomedon. Telamon, father of the Greek hero Ajax the Great, was one of the Argonauts and friend of Heracles who assisted him on his expeditions against the Amazons and his assault on Troy. Laomedon was the king of Troy at the time and father of Podarces, later renamed Priam. When Heracles besieged Troy, Telamon was the first to breach the wall and enter the city (first panel painting - Telamon approaching King Laomedon). Heracles slew Laomedon (next panel) and awarded Laomedon's daughter to Telamon as a war prize (third panel - the wedding of Telamon and Hesione).[9]

Gardens

editThe house is particularly well known for its extensive gardens and outdoor ornamentation, including two perpendicular euripi, water channels named after the strait of Euripus between Euboea and the main Greek peninsula. These channels with fountains were the centerpiece for many frescoes and statuettes.

The source of water for these extensive water features was provided by a lattice of lead piping supplied by a castellum plumbeum, a lead-lined reservoir on the northwest corner of the insula, part of a fairly complex water pressure system which functioned with the local water towers. Around 27 BCE, Pompeii was connected to the new Aqua Augusta aqueduct that ran from Sante Lucia di Serino to Misenum. Water flowed into the castellum divisorium, a distribution station on the highest point of the city near the Vesuvian gate. Due to significant height differences which caused undesirable pressure variations in the water system, a series of water towers were constructed to regulate pressures in different districts within the city. Of these, 14 have been excavated and tower 6 was found on the corner of II, 2,1 at the intersection of the Via dell'Abbondanza and the Vicolo di Octavius Quartio.[11]

The upper euripus (i), running east to west, was lined with six plinths thought to support statues of the muses. However, only one of Polyhymnia and one of Mnemosyne have been recovered and are presently in the archaeological museum in Naples. A reproduction of Mnemosyne can now be seen on site, however. Other sculptures recovered from the upper euripus include a head of a young Dionysus, a lion consuming a deer, a sphinx, another lion, a female theater mask, a hunting hound attacking a fawn, and an infant Hercules strangling a snake.

The north wall of the upper euripus was painted with a hunting scene of large felines including a leopard and antelope.

At the west end of the water channel are faded frescoes of Diana bathing and Actaeon being attacked by his own hunting hounds that flank the doorway to room (f), the space some scholars think served as a sacellum.

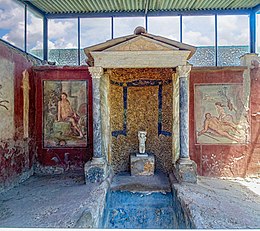

At the east end of the upper euripus, a summer biclinium (k) is constructed with two masonry couches on either side of a water feature. An aedicula is centered on the back wall flanked by a fresco of Narcissus admiring his reflection in a pool and the suicide of Pyramus and Thisbe. Telamon in the form of a kneeling satyr is now placed within the aedicula based on a suggestion by original site excavator Spinazzola but today there is no evidence of piping for its use as a fountain base. A sculpture of a river god was also found in this location.[9]

A particularly significant find on one of the couches of the summer biclinium was the only known artist's signature in Pompeii: "Lucius pinxit" or "Painted by Lucius."[2]

The lower euripus runs north to south and bisects an expansive garden of fruit trees, other shady flora and acanthus (l) planted in pergolated ordered rows. At its point of intersection with the upper euripus stands a tetrastyled temple embellished with polychrome stucco decoration. Its base is a fountain with spigots arranged in a semicircle with a vertical jet at the center.[12]

The shorter north end of the lower euripus terminates in a columned nymphaeum with stepped fountain. A marble sculpture of Cupid holding up a theater mask was found above the fountain steps in 1920. An early photograph shows the walls of the nymphaeum frescoed with a nude Diana at her bath on the left and Actaeon on the right, with a landscape on the side wall. These paintings are barely perceptible now due to exposure.

Just below the midway point of the lower euripus is a pool with a square fountain structure in its center with four sets of marble steps on each side to produce cascades of water from the central jet back. Twelve plinths may have once held decorative statues. It was once covered by a pergola suspended by four columns that has since been removed.

Near the southern end of the lower euripus is a small four-columned pavilion embellished with a stucco relief depicting swans, acanthus leaves and flowers on a red background.

The lower euripus ends in a third pool. Near the wall at the south end, a statue of Hermaphroditus was recovered. The back garden gate is across from entrance 7 of the palaestra with natatio (swimming pool) southwest of the amphitheater.[9]

Gallery

edit-

Diana bathing at west end of euripus

-

Actaeon attacked by his hunting hounds

-

Closeup of Actaeon's hounds

-

Fresco of Narcissus in the summer biclinium

-

Pyramus and Thisbe, committing suicide

-

Aedicula column capital in the summer biclinium

-

Replanted flora in the garden

-

Stucco work on small pavilion at the south end of lower euripus

-

Stepped fountain near midway point of lower euripus

-

Cupid with a theater mask found in nymphaeum

-

Roundel with heads of satyrs in room f

-

Frescoed triclinium with scenes of Heracles, Achilles and Troy

-

(L-R) Telamon and Laomedon, Heracles battling Laomedon, King of Troy, and Hesione and Telamon

-

Possible sacellum (f) with floating figure of priest of Isis

-

Room (e) with hunt scene panel

-

Closeup of panel painting with hunt scene

-

Statue of Hermaphroditus found near the south wall

References

edit- ^ "House of Octavius Quartio".

- ^ a b c Nappo, Salvatore. Pompeii: Guide to the Lost City. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1988. 32-33, 41-45, 50-51.

- ^ Varveri, A. "Places: 658295679 (House of Octavius Quartio)". Pleiades. Retrieved August 26, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Tronchin, Francesca C. "An Eclectic Locus Artis: the Casa Di Octavius Quartio At Pompeii." Diss. Boston Univ., 2006

- ^ a b c d e f "The Domus of Octavius Quartio in Pompeii: Damage Diagnosis of the Masonries and Frescoed Surfaces". International Journal of Conservation Science (7): 885–900. 2016. Retrieved 2022-06-22.

- ^ a b Clarke, John R. (1991). The Houses of Roman Italy, 100 BC - A.D. 250, Ritual Space and Decoration. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University California Press. ISBN 0-520-07267-7.

- ^ Jashemski, Wilhelmina (1979). The Gardens of Pompeii, Herculaneum, and the Villas Destroyed by Vesuvius. New Rochelle, NY. p. 48.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Condition Assessment - Regio II, Insula 2 II-2 M 280 (Formerly Regio II, Insula 5)". Pompeii Perspectives. Jennifer F. and Arthur E. Stephens. Retrieved 2022-06-25.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Domus of Loreius Tiburtinus or House of D. Octavius Quartio". Pompeii in Pictures. Jackie and Bob Dunn. Retrieved 2022-06-25.

- ^ Nicols, John, Ph.D. (2 December 2013). Civic patronage in the Roman Empire. Leiden. pp. 21–35, 29, 69, 90. ISBN 978-90-04-26171-6. OCLC 869672373.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schram, Wilke; van Opstal, Driek; Passchier, Cees. "Pompeii (Italy)". Roman Aqueducts. Wilke Schram, Utrecht University. Retrieved 2022-06-27.

- ^ Dobbins, John J.; Foss, Pedar W. (2007). World of Pompeii (2008 ed.). New York, NY: Routledge. p. 363. ISBN 978-0-415-17324-7.

External links

editMedia related to Casa di Ottavio Quartione (Pompeii) at Wikimedia Commons