The House of Wisdom (Arabic: بَيْت الْحِكْمَة Bayt al-Ḥikmah), also known as the Grand Library of Baghdad, was believed to be a major Abbasid-era public academy and intellectual center in Baghdad. In popular reference, it acted as one of the world's largest public libraries during the Islamic Golden Age,[1][2][3] and was founded either as a library for the collections of the fifth Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid (r. 786–809) in the late 8th century or as a private collection of the second Abbasid caliph al-Mansur (r. 754–775) to house rare books and collections in the Arabic language. During the reign of the seventh Abbasid caliph al-Ma'mun (r. 813 – 833 AD), it was turned into a public academy and a library.[1][4]

| House of Wisdom | |

|---|---|

| بَيْت الْحِكْمَة | |

| |

| |

| Location | Baghdad, Abbasid Caliphate (now Iraq) |

| Type | Library |

| Established | c. 8th century CE |

| Dissolved | 1258 (Mongol conquest) |

Finally, it was destroyed in 1258 during the Mongol siege of Baghdad.[4] The primary sources behind the House of Wisdom narrative date between the late eight centuries and thirteenth centuries, and most importantly include the references in Ibn al-Nadim's (d. 995) al-Fihrist.[5]

More recently, the narrative of the Abbasid House of Wisdom acting as a major intellectual center, university, and playing a sizable role during the translation movement has been understood by some historians to be a myth, constructed originally over the course of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries by Orientalists and, through their works, propagated its way into scholarship and nationally-oriented works until more recent re-investigations of the evidence.[6][7][8]

Background

editGreco-Arabic translation movement

editThe House of Wisdom existed as a part of the major Translation Movement taking place during the Abbasid Era, translating works from Greek and Syriac to Arabic, but it is unlikely that the House of Wisdom existed as the sole center of such work, as major translation efforts arose in Cairo and Damascus even earlier than the proposed establishment of the House of Wisdom.[9] This translation movement lent momentum to a great deal of original research occurring in the Muslim world, which had access to texts from Greek, Persian, and Indian sources. The rise of advanced research into mathematics, astronomy, philosophy, and medicine was the beginning of Arabic science, and drove demand for more and updated translations.[10]

Influx of scholars

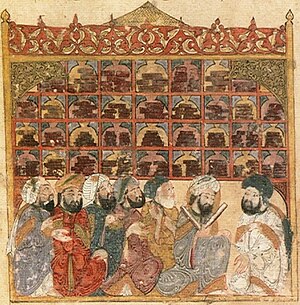

editThe House of Wisdom was made possible by the consistent flow of Arab, Persian, and other scholars of the Islamic world to Baghdad, owing to the city's position as capital of the Abbasid Caliphate.[11] This is evidenced by the large number of scholars known to have studied in Baghdad between the 8th and 13th centuries, such as al-Jahiz, al-Kindi, and al-Ghazali among others, all of whom would have contributed to a vibrant academic community in Baghdad, producing a great number of notable works, regardless of the existence of a formal academy.[11][9] The fields to which scholars associated with the House of Wisdom contributed include, but are not limited to, philosophy, mathematics, medicine, astronomy, and optics.[12][11] The early name of the library, Khizanat al-Hikma (literally, "Storehouse of Wisdom"), derives from its function as a place for the preservation of rare books and poetry, a primary function of the House of Wisdom until its destruction.[1] Inside the House of Wisdom, writers, translators, authors, scientists, scribes, and others would meet daily for translation, writing, conversation, reading, and dialogue.[13] Numerous books and documents covering several scientific concepts and philosophical subjects in different languages were translated in this house.[14]

History

editOrigins and establishment

editThroughout the 4th to 7th centuries, scholarly work in the Arabic languages was either newly initiated or carried on from the Hellenistic period. Centers of learning and of transmission of classical wisdom included colleges such as the School of Nisibis and later the School of Edessa, and the renowned hospital and medical Academy of Gondishapur; libraries included the Library of Alexandria and the Imperial Library of Constantinople; and other centers of translation and learning functioned at Merv, Salonika, Nishapur and Ctesiphon, situated just south of what was later to become Baghdad.[15][16]

During the Umayyad era, Muawiyah I started to gather a collection of books in Damascus. He then formed a library that was referred to as "Bayt al-Hikma".[17] Books written in Greek, Latin, and Persian in the fields of medicine, alchemy, physics, mathematics, astrology and other disciplines were also collected and translated by Muslim scholars at that time.[18] The Umayyads also appropriated paper-making techniques from the Chinese and joined many ancient intellectual centers under their rule, and employed Christian and Persian scholars to both translate works into Arabic and to develop new knowledge.[19][20] These were fundamental elements that contributed directly to the flourishing of scholarship in the Arab world.[18]

In 750, the Abbasid dynasty replaced the Umayyad as the ruling dynasty of the Islamic Empire, and, in 762, the Caliph al-Mansur (r. 754–775) built Baghdad and made it his capital instead of Damascus. Baghdad's location and cosmopolitan population made the perfect location for a stable commercial and intellectual center.[18] The Abbasid dynasty had a strong Persian bent,[21] and adopted many practices from the Sasanian Empire—among those, that of translating foreign works, except that now texts were translated into Arabic. For this purpose, al-Mansur founded a palace library modeled after the Sasanian Imperial Library, and provided economic and political support to the intellectuals working there.[22] He also invited delegations of scholars from India and other places to share their knowledge of mathematics and astronomy with the new Abbasid court.[18]

In the Abbasid Empire, many foreign works were translated into Arabic from Greek, Chinese, Sanskrit, Persian and Syriac. The Translation Movement gained great momentum during the reign of Caliph Harun al-Rashid, who, like his predecessor, was personally interested in scholarship and poetry. Originally the texts concerned mainly medicine, mathematics and astronomy; but other disciplines, especially philosophy, soon followed. Al-Rashid's library, the direct predecessor to the House of Wisdom, was also known as Bayt al-Hikma or, as the historian al-Qifti called it, Khizanat Kutub al-Hikma (Arabic for "Storehouse of the Books of Wisdom").[17]

Al-Ma'mun's reign

editUnder the sponsorship of Caliph al-Ma'mun (r. 813–833), economic support of the House of Wisdom and scholarship in general was greatly increased. Al-Ma'mun, under the tutelage of his father, Caliph Harun al-Rashid, memorized the Quran word for word under the eyes of leading religious scholar of the court. Al-Ma'mun's mistakes were instantly corrected. It was a common trait amongst Muslim poets, scientists, and authors to memorize their original texts for public lectures, which were typically done inside a mosque. This practice appeared to be ingrained inside al-Ma'mun's intellectual capabilities.[23]

His love for science was so great that it was said that he preferred scientific texts as the spoils of war.[2] Furthermore, Abbasid society itself came to understand and appreciate the value of knowledge, and support also came from merchants and the military.[18] It was easy for scholars and translators to make a living, and an academic life was indicative of high status in society; scientific knowledge was considered so valuable that books and ancient texts were sometimes preferred as war booty rather than riches.[17] Indeed, Ptolemy's Almagest was claimed as a condition for peace by al-Ma'mun after a war between the Abbasids and the Eastern Roman Empire.[24]

The House of Wisdom was much more than an academic center removed from the broader society. Its experts served several functions in Baghdad. Scholars from the Bayt al-Hikma usually doubled as engineers and architects in major construction projects, kept accurate official calendars, and were public servants. They were also frequently medics and consultants.[18]

Al-Ma'mun was personally involved in the daily life of the House of Wisdom, regularly visiting its scholars and inquiring about their activities. He would also participate in and arbitrate academic debates.[18] One of the reasons that al-Ma'mun loved the pursuit of knowledge was said to be from a dream that he once had. In the dream, he was said to have been visited by Aristotle, where they had a discussion on what was good.[25] Inspired by Aristotle, al-Ma'mun regularly initiated discussion sessions and seminars among experts in Kalām; Kalām being an art of philosophical debate, which al-Ma'mun carried on from his Persian tutor, Ja’far. During such debates, scholars would discuss their fundamental Islamic beliefs and doctrines in an open, intellectual atmosphere.[2] He would often organize groups of sages, from the Bayt al-Hikma, into major research projects to satisfy his own intellectual curiosities. For example, he commissioned the mapping of the world, the confirmation of data from the Almagest and the deduction of the real size of the Earth (see section on the main activities of the House). He also promoted Egyptology and personally participated in excavations at the pyramids of Giza.[26] Al-Ma’mun built the first astronomical observatories in Baghdad, and he was also the first ruler to fund and monitor the progress of major research projects involving teams of scholars and scientists. In this way he was the first ruler to fund "big science".[27]

Following his predecessors, al-Ma'mun would send expeditions of scholars from the House of Wisdom to collect texts from foreign lands. In fact, one of the directors of the House was sent to Constantinople with this purpose. During this time, Sahl ibn Harun, a Persian poet and astrologer, was the chief librarian of the Bayt al-Hikma. Hunayn ibn Ishaq (809–873), an Arab Nestorian Christian physician and scientist, was the most productive translator, producing 116 works for the Arabs. As "Sheikh of the translators," he was placed in charge of the translation work by the caliph. Hunayn ibn Ishaq translated the entire collection of Greek medical books, including famous pieces by Galen and Hippocrates.[28] The Sabian Thābit ibn Qurra (826–901) also translated great works by Apollonius, Archimedes, Euclid and Ptolemy. Translations of this era were superior to earlier ones, since the new Abbasid scientific tradition required better and better translations, and the emphasis was many times put on incorporating new ideas to the ancient works being translated.[18][29] By the second half of the ninth century, al-Ma'mun's Bayt al-Hikma was the greatest repository of books in the world and had become one of the greatest hubs of intellectual activity during the Medieval era, attracting the most brilliant Arab and Persian minds.[17] The House of Wisdom eventually acquired a reputation as a center of learning, although universities as they are modernly known did not yet exist at this time—knowledge was transmitted directly from teacher to student without any institutional surrounding. Maktabs soon began to develop in the city from the 9th century on and, in the 11th century, Nizam al-Mulk founded the Al-Nizamiyya of Baghdad, one of the first institutions of higher education in Iraq.

Al-Mutawakkil's reign

editThe House of Wisdom flourished under al-Ma'mun's successors al-Mu'tasim (r. 833–842) and his son al-Wathiq (r. 842–847), but considerably declined under the reign of al-Mutawakkil (r. 847–861). Although al-Ma'mun, al-Mu'tasim, and al-Wathiq followed the sect of Mu'tazili, which supported broad-mindedness and scientific inquiry, al-Mutawakkil endorsed a more literal interpretation of the Qur'an and Hadith. The caliph was not interested in science and moved away from rationalism, seeing the spread of Greek philosophy as anti-Islamic.[30]

Destruction by the Mongol army

editOn February 13, 1258, the Mongols entered the city of the caliphs, starting a full week of pillage and destruction.

Along with all other libraries in Baghdad, the House of Wisdom was destroyed by Hulagu's army during the Siege of Baghdad.[31] The books from Baghdad's libraries were thrown into the Tigris River in such quantities that the river was said to have run black with the ink from their pages.[32] According to a 16th century chronicle about the siege from Quṭb al-Dīn al-Nahrawālī, "So many books were thrown into the Eufrates River that they formed a bridge that would support a man on horseback." According to historian Michal Biran, this quote was a literary trope associated with the siege of Baghdad and magnifying Mongol barbarity.[33] Nasir al-Din al-Tusi rescued about 400,000 manuscripts, which he took to Maragheh before the siege.[34]

Many of the books were also torn apart by pillagers so that the leather covers could be made into sandals.[35]

Main activities

editThe House of Wisdom included a society of scientists and academics, a translation department, and a library that preserved the knowledge acquired by the Abbasids over the centuries.[18] Research and study of alchemy, which was later used to form the structure of modern chemistry, was also conducted there. Further, it was also linked to astronomical observations and other major experimental endeavors.

Institutionalized by al-Ma'mun, the academy encouraged the transcription of Greek philosophical and scientific efforts. Additionally, he imported manuscripts of important texts that were not accessible to the Islamic countries from Byzantium to the library.

The House of Wisdom was much more than a library, and a vast amount of original scientific and philosophical work was produced by scholars and intellectuals in relation to it (although many were lost due to the destruction of the library). This allowed Muslim scholars to verify astronomical information that was handed down from past scholars.[2]

Translations from Greece, India, and Persia

editThe Translation Movement lasted for two centuries and was a large contributing factor to the growth of scientific knowledge during the golden age of Arabic science. Ideas and wisdom from other cultures around the world, Greece, India, and Persia, were translated into Arabic contributing to further advances in the Islamic Empire. An important goal during this time was to create a comprehensive library that contained all of the knowledge gained throughout this movement. Advances were made in areas like mathematics, physics, astronomy, medicine, chemistry, philosophy, and engineering. The influential achievement of translation revealed to scholars in the empire to the limitless body of early knowledge in the Ancient Near East and Greek traditions, developing the birth of primary scholarship beyond philosophy and scholarship. The engagement across arts and sciences assorts and stretches intelligence realms and brings growth to new methods of understanding. This was accomplished through academic knowledge and creative rehearsal.[36] The House of Wisdom was known for being a space for scholarly growth and contribution which during the time greatly contributed to the Translation Movement.[37]

The Translation Movement started in this House of Wisdom and lasted for over two centuries. Over a century and a half, primarily Middle Eastern Oriental Syriac Christian scholars translated all scientific and philosophic Greek texts into Arabic language in the House of Wisdom.[38][39] The translation movement at the House of Wisdom was inaugurated with the translation of Aristotle's Topics. By the time of al-Ma'mun, translators had moved beyond Greek astrological texts, and Greek works were already in their third translations.[1] Authors translated include: Pythagoras, Plato, Aristotle, Hippocrates, Euclid, Plotinus, Galen, Sushruta, Charaka, Aryabhata and Brahmagupta. Many important texts were translated during this movement including a book about the composition of medicinal drugs, a book on this mixing and the properties of simple drugs, and a book on medical matters by Pedanius Dioscorides. These, and many more translations, helped with the advancements in medicine, agriculture, finance, and engineering.

Furthermore, new discoveries motivated revised translations and commentary correcting or adding to the work of ancient authors.[18] In most cases names and terminology were changed; a prime example of this is the title of Ptolemy's Almagest, which is an Arabic modification of the original name of the work: Megale Syntaxis.[18]

Original contributions

editBesides their translations of earlier works and their commentaries on them, scholars at the Bayt al-Ḥikma produced important original research. For example, the noted mathematician al-Khwarizmi worked in al-Maʾmun’s House of Wisdom and is famous for his contributions to the development of algebra.

Abū Yūsuf Yaʿqūb ibn Isḥaq al-Kindī[40] was also another historical figure that worked at the House of Wisdom. He studied cryptanalysis but he was also a great mathematician. Al-Kindī is the most famous for being the first person to introduce Aristotle's philosophy to the Arabic people. He fused Aristotle's philosophy with Islamic theology, which created an intellectual platform for philosophers and theologians to debate over 400 years. A fellow expert on Aristotle was Abū ʿUthmān al-Jāḥiẓ, who was born in Basra around 776 but he spent most of his life in Baghdad. Al-Ma’mun employed al-Jāḥiẓ as a personal tutor for his children, but he had to dismiss him because al-Jāḥiẓ was "goggled-eyed", i.e., he had wide, staring eyes which made him frightening to look at. Al-Jāḥiẓ was one of the few Muslim scholars who was deeply concerned with biology. He wrote Book of Animals, which discusses the way animals adapt to their surroundings, similarly to Aristotle's History of Animals.[41] In his book, al-Jāḥiẓ argued that animals like dogs, foxes, and wolves must have descended from a common ancestor because they shared similar characteristics and features such as four legs, fur, tail, and so on.

Mūsā ibn Shākir was an astrologer and a friend of Caliph Harun al-Rashid's son, al-Ma'mun. His sons, collectively known as the Banū Mūsā (Sons of Moses), also contributed with their extensive knowledge of mathematics and astrology. When their father died, al-Ma'mun became their guardian. Between 813 and 833, the three brothers were successful in their works in science, engineering, and patronage.[42] Abū Jaʿfar, Muḥammad ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir (before 803 – February 873), Abū al‐Qāsim, Aḥmad ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir (d. 9th century) and al-Ḥasan ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir (d. 9th century) are widely known for their Book of Ingenious Devices, which describes about one hundred devices and how to use them. Among these was "The Instrument that Plays by Itself", the earliest example of a programmable machine,[43][citation needed] as well as the Book on Measurement of Plane and Spherical Figures. Mohammad Musa and his brothers Ahmad and Hasan contributed to Baghdad's astronomical observatories under the Abbasid Caliph al-Ma'mun, in addition to House of Wisdom research.[44] Having shown much potential, the brothers were enrolled in the library and translation center of the House of Wisdom in Baghdad. They began translating ancient Greek into Arabic after quickly mastering the language, as well as paying large sums to obtain manuscripts from the Byzantine Empire for translation.[45] They also made many original contributions to astronomy and physics. Mohammad Musa might have been the first person in history to point to the universality of the laws of physics.[2] In the 10th century, Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) performed several physical experiments, mainly in optics, achievements still celebrated today.[46]

In medicine, Hunayn wrote an important treatise on ophthalmology. Other scholars also wrote on smallpox, infections and surgery. Note that these works would later become standard textbooks of medicine during the European Renaissance.[47]

Under al-Ma'mun's leadership science saw for the first time wide-ranging research projects involving large groups of scholars. In order to check Ptolemy's observations, the caliph ordered the construction of the first astronomical observatory in Baghdad (see Observatories section below). The data provided by Ptolemy was meticulously checked and revised by a highly capable group of geographers, mathematicians and astronomers.[18] Al-Ma'mun also organized research on the circumference of the Earth and commissioned a geographic project that would result in one of the most detailed world-maps of the time. Some consider these efforts the first examples of large state-funded research projects.[48]

Astronomical observatories

editThe creation of the first astronomical observatory in the Islamic world was ordered by Caliph al-Ma'mun in 828 in Baghdad. The construction was directed by scholars from the House of Wisdom: senior astronomer Yahya ibn abi Mansur and the younger Sanad ibn Ali al-Alyahudi.[49] It was located in al-Shammasiyya and was called Maumtahan Observatory. After the first round of observations of Sun, Moon and the planets, a second observatory on Mount Qasioun, near Damascus, was constructed. The results of this endeavor were compiled in a work known as al-Zij al-Mumtahan, which translates as "The Verified Tables".[48][50]

Dispute theory of Dimitri Gutas

editYale University Arabist Dimitri Gutas disputes the existence of the House of Wisdom as well as its form and function. He posits in his 1998 book that "House of Wisdom" is a translation error from Khizanat al-Hikma, which he asserts simply means a storehouse, and that there are few sources from the era during the Abbasid Era that mention the House of Wisdom by the name Bayt al-Hikma.[1] Gutas asserts that, without consistent naming conventions, a physical ruin, or corroborating texts, the phrase "House of Wisdom" may just as well have been a metaphor for the larger Academic community in Baghdad rather than a physical academy specializing in translation work.[1] Gutas mentions that in all of the Graeco-Arabic translations none of them mention the House of Wisdom, including the notable Hunayn ibn Ishaq.[51] There is also no proof that the Sultan ever held open debates among scholars in the library since that would not have been socially acceptable.[1] This theory is debatable, owing to the destruction of the Round city of Baghdad and conflicting sources in both academic texts and poetry.[52][4] It is likely, given the Abbasid caliphs' patronage of the arts and sciences, that an extensive library existed in Baghdad, and that scholars could have access to such texts, judging by the volume of work produced by scholars centered in Baghdad.[4] There is a strong chance that the library was only used to preserve history from the Sassanian Dynasty and the translations that were done there were only done to achieve that goal.[53] Once the Abbasids took over they most likely continued this tradition with the added goal of pursuing both astrology and astronomy.[1]

Notable intellectuals

editThis is a list of notable people related to the House of Wisdom.[11]

- Abu Ma'shar al-Balkhi (786–886)—leading Persian astrologist in the Abbasid court who translated the works of Aristotle

- Averroes (1126–1198)—born in Islamic Iberia (modern day Spain), he was a Muslim philosopher who was famous for his commentary on Aristotle

- Avicenna (980–1037)—Persian philosopher and physician famous for writing The Canon of Medicine, the prevailing medical text in the Islamic World and Europe until the 19th century[9]

- Al-Ghazali (1058–1111)—Persian theologian who was the author of The Incoherence of the Philosophers, which challenged the philosophers who favored Aristotelianism

- Muhammad al-Idrisi (1099–1169)—Arab geographer who worked under Roger II of Sicily and contributed to the Map of the World

- Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi (d. 850)—Persian polymath head of the House of Wisdom, founder of Algebra, the word "algorithm" was named after him.

- Al-Kindi (d. 873)—considered to be among the first Arab philosophers, he combined the ideology of Aristotle and Plato

- Maslama al-Majriti (950–1007)—Arab mathematician and astronomer who translated Greek texts

- Hunayn ibn Ishaq (809–873)—Arab (Nestorian Christian) scholar and philosopher who was placed in charge of the House of Wisdom. In his lifetime he translated over 116 writings by many of the most significant scholars in history.

- The Banu Musa brothers—remarkable engineers and mathematicians of Persian descent

- Sahl ibn Harun (d. 830)—philosopher and polymath

- Al-Ḥajjāj ibn Yūsuf ibn Maṭar (786–833)—Sabian mathematician and a translator who was known for his translation of Euclid's works

- Thābit ibn Qurra (826–901)—Sabian mathematician, astronomer and translator who reformed Ptolemaic system. Considered as the founding father of statics.[54]

- Yusuf al-Khuri (d. 912)— mathematician and astronomer who was hired as a translator by Banu Musa brothers

- Qusta ibn Luqa (820–912)—mathematician and physician who translated Greek texts into Arabic

- Abu Bishr Matta ibn Yunus (870–940)— Christian physician, scientist and translator

- Yahya ibn al-Batriq (796–806)— Assyrian Christian astronomer and translator

- Yahya ibn Adi (893–974)— Syriac Jacobite Christian philosopher, theologian and translator

- Sind ibn Ali (d. 864)—astronomer who translated and reworked Zij al-Sindhind

- Al-Jahiz (781–861)—author and biologist known for Kitāb al-Hayawān and numerous literary works

- Ismail al-Jazari (1136–1206)—physicist and engineer who is best known for his work in writing The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices in 1206

- Omar Khayyam (1048–1131)—Persian poet, mathematician, and astronomer most famous for his solution of cubic equations

Other "Houses of Wisdom"

editA major contribution from the House of Wisdom in Baghdad is the influence it had on other libraries in the Islamic world. It has been recognised as a factor that connected many different people and empires because of its educational and research components. The House of Wisdom has been accredited and respected throughout Islamic history and was the model for many libraries during and following its time of function. A large number of libraries emerged during and after this time and it was evident that these libraries were based on the House of Wisdom in Baghdad. These libraries had the intention of reproducing the advantageous and beneficial characteristics that are known throughout the world because of the House of Wisdom.[55]

Some other places have also been called House of Wisdom, which should not be confused with Baghdad's Bayt al-Hikma:

- In Cairo, Dar al-Hikmah, the "House of Wisdom", was another name of the House of Knowledge, founded by the Fatimid Caliph, al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah in 1004.[2] Included in this House of Knowledge was a library that had a collection so vast, it was known as a "Wonder of the World". The beginning of the foundation of Cairo's House of Wisdom was by Fatimid al-Aziz billah who was a lover of books and collected a vast amount of them. He was determined to collect every book that was authored or translated in the Baghdad House of Wisdom. The actual founder al-Hākim bi-Amr Allah, assembled a group of scholars to work in the library by authoring books and contributing to the scientific knowledge acquired in this place. He provided a large amount of supplies like ink, paper, and anything else that the scholars may have needed in order to make their contributions.[55]

- The Aghlabids House of Wisdom founded in Raqqada by Amir Ibrahim Ibn Mohammad al-Aghlabī. Ibrahim was enticed by the acquisition of knowledge and knew the positive qualities that education, scholarship, and innovative ideas brought to societies around the world. A multitude of scholarly manuscripts, scientific journals, and books were found here with the intent to create a library with an equivalent reputation to the Baghdad House of Wisdom. A group of scholars would journey to Baghdad annually to retrieve important literary works and other writings and bring them back to the library which helped contribute to the unique and rare material found in the Aghlabids House of Wisdom.[55]

- The Andalusian House of Wisdom founded in Andalusia by an Umayyad caliph, al-Hakam al-Mustansir, who was known as a master of scholar for his knowledge in many different scientific categories. He started one of the largest collections of manuscripts, writings, and books that consisted of a multitude of genres and scientific categories. The Andalusian House of Wisdom was constructed based on the Baghdad House of Wisdom and was used to store the vast amount of knowledge acquired by al-Mustansir. During this period scientific development, art, architecture, and much more grew and prospered.[55]

- There is a research institute in Baghdad called Bayt Al-Hikma after the Abbasid-era research center. While the complex includes a 13th-century madrasa (33°20′32″N 44°23′01″E / 33.3423°N 44.3836°E), it is not the same building as the medieval Bayt al-Hikma. It was damaged during the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

- Beït al-Hikma (House of Wisdom), Tunis, Tunisia, established in 1983.

- The main library at Hamdard University in Karachi, Pakistan, is called 'Bait al Hikmat'.

- La Maison de Sagesse (House of Wisdom), an international NGO based in France.[56][57]

- The House of Wisdom دارالحکمة س, Tehran, Iran, established in 2017 by Alireza Mohammadi.

- The House of Wisdom, Fez, Morocco, established in 2018 by Cardinal Barbarin and Khal Torabully.[58][59]

See also

editNotes and references

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h Dimitri Gutas (1998). Greek Thought, Arabic Culture: The Graeco-Arabic Translation Movement in Baghdad and Early ʻAbbāsid Society (2nd–4th/8th–10th Centuries). Psychology Press. pp. 53–60. ISBN 978-0415061322.

- ^ a b c d e f Jim Al-Khalili (2011). "5: The House of Wisdom". The House of Wisdom: How Arabic Science Saved Ancient Knowledge and Gave Us the Renaissance. Penguin Publishing Group. p. 53. ISBN 978-1101476239.

- ^ Chandio, Abdul Rahim (January 2021). "The house of wisdom (Bait Al-Hikmah): A sign of glorious period of Abbasids caliphate and development of science". International Journal of Engineering and Information Systems. ISSN 2643-640X. Archived from the original on March 26, 2023. Retrieved July 9, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Brentjes, Sonja; Morrison, Robert G. (2010). "The Sciences in Islamic Societies". The New Cambridge History of Islam. Vol. 4. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 569. ISBN 978-0521838245

- ^ İhsanoğlu, Ekmeleddin (2023). The Abbasid house of wisdom: between myth and reality. London New York, NY: Routledge. pp. 9, 25. ISBN 978-1-032-34745-5.

- ^ İhsanoğlu, Ekmeleddin (2023). The Abbasid house of wisdom: between myth and reality. London New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-032-34745-5.

- ^ Khaleb, Dana (2023). "Ekmeleddin Ihsanoğlu, Abbasid House of Wisdom". Almagest. 14 (1): 210–214. doi:10.1484/J.ALMAGEST.5.134615. ISSN 1792-2593.

- ^ Hannam, James (2023). The globe: how the Earth became round. London: Reaktion books. p. 182. ISBN 978-1-78914-758-2.

- ^ a b c Pormann, Peter E.; Savage-Smith, Emilie (2007). Medieval Islamic medicine. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. pp. 20–29. ISBN 978-1589011601. OCLC 71581787.

- ^ Lyons, Jonathan (2008). The House of Wisdom. p. 64.[ISBN missing]

- ^ a b c d Lyons, Jonathan (2009). The house of wisdom : how the Arabs transformed Western civilization. New York: Bloomsbury Press. ISBN 9781596914599.

- ^ Al-Khalili 2011, p. 88

- ^ Algeriani, Adel Abdul-Aziz; Mohadi, Mawloud (September 11, 2017). "The House of Wisdom (Bayt al-Hikmah) and Its Civilizational Impact on Islamic libraries: A Historical Perspective". Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences. 8 (5): 179–187. doi:10.1515/mjss-2017-0036. S2CID 55170291. Archived from the original on July 16, 2022. Retrieved July 16, 2022 – via CORE.

- ^ "The House of Wisdom: Baghdad's Intellectual Powerhouse". 1001 inventions. May 22, 2019. Archived from the original on December 4, 2021. Retrieved December 4, 2021.

- ^ Kaser, Karl The Balkans and the Near East: Introduction to a Shared History Archived 2015-11-28 at the Wayback Machine p. 135.

- ^ Yazberdiyev, Dr. Almaz Libraries of Ancient Merv Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine Dr. Yazberdiyev is Director of the Library of the Academy of Sciences of Turkmenistan, Ashgabat.

- ^ a b c d Al-Khalili 2011, pp. 67–78

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Lyons 2008, pp. 55–77

- ^ Meri, Josef W. and Jere L. Bacharach. “Medieval Islamic Civilization”. Vol. 1 Index A–K. 2006, p. 304.

- ^ Brague, Rémi (2009). The Legend of the Middle Ages: Philosophical Explorations of Medieval Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. University of Chicago Press. p. 164. ISBN 9780226070803.

Neither were there any Muslims among the Ninth-Century translators. Amost all of them were Christians of various Eastern denominations: Jacobites, Melchites, and, above all, Nestorians.

- ^ "Wiet. Baghdad". Archived from the original on January 7, 2010. Retrieved December 22, 2006.

- ^ Mohadi, Mawloud (February 2019). "The House of Wisdom (Bayt al-Hikmah), an Educational Institution during the Time of the Abbasid Dynasty. A Historical Perspective". Pertanika Journal of Social Science and Humanities. 27 (2): 1297–1313.

- ^ Lyons, Jonathan (2008). The House of Wisdom. p. 65.

- ^ Joseph A. Angelo (2014). Encyclopedia of Space and Astronomy. Infobase Publishing. p. 78. ISBN 978-1438110189.

- ^ Brentjes, Sonja; Morrison, Robert G. (January 1, 2000). "The sciences in Islamic societies (750–1800)". In Irwin, Robert (ed.). The New Cambridge History of Islam (1 ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 564–639. doi:10.1017/chol9780521838245.024. ISBN 978-1139056144. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ Al-Khalili 2011, p. 64

- ^ Al-Khalili 2011, p. 58

- ^ Iskandar, Albert Z. (2008). "Ḥunayn Ibn Isḥāq". In Selin, Helaine (ed.). Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. pp. 1081–1083. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-4425-0_9796. ISBN 978-1402045592.

- ^ Gingerish, Owen (April 1986). "Islamic Astronomy". 4. 254: 74–83.

- ^ Al-Khalili 2011, p. 135

- ^ Al-Khalili 2011, p. 233

- ^ "The Mongol Invasion and the Destruction of Baghdad". Lost Islamic History. Archived from the original on August 14, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2014.

- ^ Michal Biran, "Libraries, Books, and Transmission of Knowledge in Ilkhanid Baghdad", Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 62, 2-3 (2019): 470-471.

- ^ Saliba 2007, p. 243

- ^ Murray, Stuart (2019). The Library: An Illustrated History. Skyhorse Publishing Company, Inc. pp. 33–43. ISBN 978-1628733228.

- ^ Suzy, Elhafez (July 14, 2017). "The House of Wisdom: Interdisciplinarity in the Arab-Islamic Empire". The Academic Platform. Archived from the original on December 10, 2021. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- ^ Al-Khalili 2011, pp. 107–133

- ^ Rosenthal, Franz The Classical Heritage in Islam The University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1975, p. 6[ISBN missing]

- ^ Adamson, London Peter The Great Medieval Thinkers: Al-Kindi Oxford University Press, New York, 2007, p. 6. London [ISBN missing], Peter Adamson is a Lecturer in Late Ancient Philosophy at King's College.

- ^ Al-Khalili 2011, p. 88

- ^ Al-Jahiz, Kitab al-Haywān, vol. 4 (Al-Matba’ah al-Hamīdīyah al-Misrīyah, Cairo, 1909), p. 23

- ^ Nizamoglu, Cem (August 10, 2007). "The mechanics of Banu Musa in the light of modern system and control engineering". MuslimHeritage.com (Book review). Manchester, UK: Foundation for Science, Technology and Civilisation. Archived from the original on April 25, 2018. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- ^ Koetsier 2001

- ^ Josep Casulleras (2007). "Banū Mūsā". In Virginia Trimble; Thomas R. Williams; Katherine Bracher; Richard Jarrell; Jordan D. Marché; F. Jamil Ragep (eds.). Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 92–93. ISBN 978-0387304007.

- ^ Ehsan Masood (2009). Science & Islam: A History. Icon Books Limited. pp. 161–163. ISBN 978-1848311602.

- ^ Al-Khalili 2011, pp. 152–171

- ^ Moore 2011

- ^ a b Al-Khalili 2011, pp. 79–92

- ^ Hockey 2007, p. 1249

- ^ Zaimeche 2002, p. 2

- ^ Gutas, Dimitri (1998). Greek Thought, Arabic Culture: The Graeco-Arabic Translation Movement in Baghdad and Early 'Abbasaid Society (2nd-4th/5th-10th c.) (Arabic Thought and Culture). p. 59.

- ^ Lyons, Jonathan (2014). "Bayt al-Hikmah". In Kalin, Ibrahim (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Science, and Technology in Islam. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Hayrettín Yücesoy (2009). "Translation as Self-Consciousness: Ancient Sciences, Antediluvian Wisdom, and the 'Abbāsid Translation Movement". Journal of World History. 20 (4): 523–557. doi:10.1353/jwh.0.0084. ISSN 1527-8050. S2CID 145580480.

- ^ Holme, Audun (2010). Geometry : our cultural heritage (2nd ed.). Berlin: Springer. ISBN 9783642144417. OCLC 676701072.

- ^ a b c d Algeriani, Adel Abdul-Aziz; Mohadi, Mawloud (September 1, 2017). "The House of Wisdom (Bayt al-Hikmah) and Its Civilizational Impact on Islamic libraries: A Historical Perspective". Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences. 8 (5): 179–187. doi:10.1515/mjss-2017-0036. ISSN 2039-2117.

- ^ "La Maison de Sagesse". Archived from the original on December 18, 2016.

- ^ "PRIX INTERNATIONAL MÉMOIRE POUR LA DÉMOCRATIE ET LA PAIX 2016 : La Maison de la Sagesse présélectionnée | Le Mauricien". www.lemauricien.com (in French). April 12, 2016. Archived from the original on September 13, 2017. Retrieved September 13, 2017.

- ^ MATIN, LE (February 17, 2018). "Le Matin - Les nouvelles Routes de la soie, un appel à la Convivencia". Le Matin. Archived from the original on May 7, 2018. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- ^ "Potomitan - Samarkand : L'Institut international d'études sur l'Asie centrale (IICAS) et la MDS Fès-Grenade, une signature historique pour la convivencia". www.potomitan.info. Archived from the original on November 2, 2020. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

Bibliography

edit- Al-Khalili, Jim (2011). The House of Wisdom: How Arabic Science Saved Ancient Knowledge and Gave Us the Renaissance. New York: Penguin Press. ISBN 978-1594202797.

- Lyons, Jonathan (2009). The House of Wisdom: How the Arabs Transformed Western Civilization. New York: Bloomsbury Press. ISBN 978-1596914599.

- Meri, Joseph; Bacharach, Jere (2006). Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415966900.

- Hockey, Thomas (2007). The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-0387304007.

- Koetsier, Teun (2001). "On the prehistory of programmable machines: musical automata, looms, calculators". Mechanism and Machine Theory. 36 (5): 589–603. doi:10.1016/S0094-114X(01)00005-2.

- Micheau, Francoise. The Scientific Institutions in the Medieval Near East. in Morelon & Rashed 1996, pp. 985–1007

- Moore, Wendy (February 28, 2011). "All the world's knowledge". BMJ. 342: d1272. doi:10.1136/bmj.d1272. PMID 21357350. S2CID 5972745.

- McKensen, Ruth Stellhorn 1932. “Four Great Libraries of Medieval Baghdad.” Library Quarterly 2 (January): 279–99.

- Morelon, Régis; Rashed, Roshdi (1996). Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science. Vol. 3. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415124102.

- George Saliba (2007), Islamic science and the making of the European Renaissance, MIT Press

- Zaimeche, Salah (2002). "A cursory review of Muslim observatories" (PDF). Manchester: Foundation for Science, Technology and Civilisation.