This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2024) |

How to Marry a Millionaire is a 1953 American romantic comedy film directed by Jean Negulesco and written and produced by Nunnally Johnson. The screenplay was based on the plays The Greeks Had a Word for It (1930) by Zoe Akins and Loco (1946) by Dale Eunson and Katherine Albert.[citation needed]

| How to Marry a Millionaire | |

|---|---|

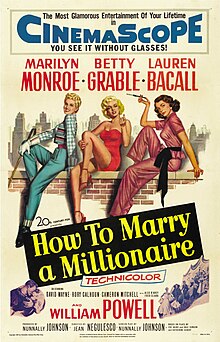

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Jean Negulesco |

| Screenplay by | Nunnally Johnson |

| Based on | The Greeks Had a Word for It by Zoe Akins Loco by Dale Eunson Katherine Albert |

| Produced by | Nunnally Johnson |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Joseph MacDonald |

| Edited by | Louis R. Loeffler |

| Music by |

|

Production company | |

| Distributed by | 20th Century-Fox |

Release date |

|

Running time | 95 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1.9 million[1] |

| Box office | $8 million[2] |

It stars Betty Grable, Marilyn Monroe, and Lauren Bacall as three fashionable Manhattan models, along with William Powell, David Wayne, Rory Calhoun, and Cameron Mitchell as their wealthy marks.

Produced and distributed by 20th Century-Fox, How to Marry a Millionaire was the studio's first film to be shot in the new CinemaScope wide-screen sound process, although it was the second CinemaScope film released by Fox after the biblical epic film The Robe (also 1953). It was also the first color and CinemaScope film ever shown on prime-time network television (though panned-and-scanned) when it was presented as the first film on NBC's Saturday Night at the Movies on September 23, 1961.[3]

The soundtrack to How to Marry a Millionaire was released on CD by Film Score Monthly on March 15, 2001.[citation needed]

Plot

editResourceful Schatze Page, spunky Loco Dempsey, and ditzy Pola Debevoise are three women on a mission: each wants to marry a millionaire. To accomplish this task, they rent a luxurious Sutton Place penthouse in New York City from Freddie Denmark (who is avoiding the IRS by living in Europe) and together hatch a plot to court the city's elite. On the day they move in, Loco arrives with Tom Brookman, who purchases her groceries for her because she "forgot her pocketbook". Tom shows interest in Schatze but she dismisses him, stating that "The first rule is, gentlemen callers have got to wear a necktie" and, instead, sets her sights on the charming, classy, rich widower J.D. Hanley. While courting the older J.D., she fends off Tom, who eventually wins her over. After every date, she insists she never wants to see him again.

Meanwhile, Loco meets grumpy businessman Walter Brewster. He is married, but she agrees to accompany him to his lodge in Maine, thinking it is a convention hall of the Elks Club. Just as Loco discovers her mistake, she comes down with the measles and is quarantined. Upon recovering, while Brewster is now bedridden with measles, she begins seeing the forest ranger, Eben Salem. Loco mistakenly believes Salem is a wealthy landowner instead of a civil servant overseeing acres of forestlands. She is disappointed, telling off Brewster on the drive back to New York.

Pola is myopic but hates wearing glasses in the presence of men. She falls for a phony oil tycoon, J. Stewart Merrill, unaware that he is a crooked speculator. When she takes a plane from LaGuardia Airport to meet him in Atlantic City, she ends up on the wrong plane to Kansas City. On the plane, she encounters the mysterious Freddie Denmark again, having unknowingly met him when he entered his apartment to retrieve his tax documents as proof that his crooked accountant stole his money and left him in trouble with the IRS. Freddie also wears glasses and encourages Pola to wear hers as well. They fall quickly in love and get married.

Loco and Pola are reunited with Schatze just before her wedding to J.D. Hanley. Schatze is unable to go through with the marriage and confesses to J.D. that she loves Tom. He agrees to call off the ceremony. Tom is among the wedding guests and the two reconcile and marry. Afterwards, the three happy couples end up at a greasy spoon diner. Schatze jokingly asks Eben and Freddie about their financial prospects, which are slim. When she finally gets around to Tom, he casually admits a net worth of around $200 million, which no one takes seriously. He then calls for the check, pulls out an enormous wad of money, and pays with a $1,000 bill, telling the chef to keep the change. The three astonished women faint, and the men drink a toast to their unconscious wives.

Cast

edit- Betty Grable as Loco Dempsey

- Marilyn Monroe as Pola Debevoise

- Lauren Bacall as Schatze Page

- David Wayne as Freddie Denmark

- Rory Calhoun as Eben Salem

- Cameron Mitchell as Tom Brookman

- Alex D'Arcy as J. Stewart Merrill

- Fred Clark as Waldo Brewster

- William Powell as J. D. Hanley

Production

editNunnally Johnson, who adapted the screenplay from two different plays, produced the picture.[4]

20th Century-Fox started production on The Robe before it began How to Marry a Millionaire. Although the latter was completed first, the studio chose to present The Robe as its first CinemaScope picture in late September or early October 1953 because it felt the family-friendly The Robe would attract a larger audience to its new widescreen process.[5]

The film's cinematography was by Joseph MacDonald. The costume design was by Travilla.[6]

Portrayal of New York

editBetween scenes, the cinematography has some iconic color views of mid-20th century New York City: Rockefeller Center, Central Park, the United Nations Building, and Brooklyn Bridge in the opening sequence following the credits. Other iconic views include the Empire State Building, the lights of Times Square at night and the George Washington Bridge.

Music

editA song extolling the virtues of New York follows the Gershwin-like music used for the title credits, after an elaborate five-minute pre-credit sequence showcasing a 70-piece orchestra conducted by Alfred Newman before the curtain goes up.[7]

The score for How To Marry a Millionaire was one of the first recorded for film in stereo. It was composed and directed by Alfred Newman, with incidental music by Cyril Mockridge, and orchestrated by Edward B. Powell.[8] The album was released on CD by Film Score Monthly on March 15, 2001[9] as part of their series Golden Age Classics.

The film's theatrical version begins with a nearly six-minute overture of Newman's symphonic piece "Street Scene", which he wrote in the style of George Gershwin. It is played on-screen by an 80-piece studio orchestra (billed as "The Twentieth Century Fox Symphony Orchestra"). Newman wrote the piece for the 1931 film Street Scene, which featured his first complete film score.

Release

editRelease and box office

editThe film premiered at the Fox Wilshire Theatre (now the Saban Theatre), in Beverly Hills, California on November 4, 1953.[10] It was a box office success, earning $8 million worldwide[2] and $7.5 million domestically, second that year only to The Robe.[11] It was the fourth highest-grossing film of 1953, whereas Monroe's previous feature, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, was seventh.

Critical response

editThe New York Times's Bosley Crowther wrote "the substance is still insufficient for the vast spread of screen which CinemaScope throws across the front of the theatre, and the impression it leaves is that of nonsense from a few people in a great big hall."[12]

On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 82% of 28 critics' reviews are positive, with an average rating of 7.2/10.[13]

Award nominations

edit| Award | Category | Subject | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards[14] | Best Costume Design – Color | Charles LeMaire and William Travilla | Nominated |

| British Academy Film Awards[15] | Best Film from any Source | How to Marry a Millionaire | Nominated |

| Writers Guild of America Awards[16] | Best Written American Comedy | Nunnally Johnson | Nominated |

Television adaptation

editIn 1957, the film was adapted into a sitcom also titled How to Marry a Millionaire. It starred Barbara Eden (as Loco Jones), Merry Anders (Michelle "Mike" Page), Lori Nelson (Greta Lindquist) and as Nelson's later replacement, Lisa Gaye as Gwen Kirby. It aired in syndication for two seasons.

Remake

editIn 2000, 20th Century Fox Television produced a made-for-TV remake, How to Marry a Billionaire: A Christmas Tale. It reversed the sex roles, and had three men looking to marry wealthy women. It starred John Stamos, Joshua Malina and Shemar Moore.

In 2007, Nicole Kidman bought the rights to How to Marry a Millionaire under her production company Blossom Films, intending to produce and possibly star in a remake.[17]

References

edit- ^ Solomon 1989, p. 248.

- ^ a b Solomon 1989, p. 89.

- ^ Gomery, Douglas; Pafort-Overduin, Clara (2011). Movie History: A Survey (2nd ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 246. ISBN 978-1-1368-3525-4.

- ^ "Facts about "How to Marry a Millionaire"". Classic Movie Hub. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ Churchwell, Sarah (December 27, 2005). The Many Lives of Marilyn Monroe. Picador. p. 57. ISBN 0-312-42565-1.

- ^ "How to Marry a Millionaire (1953): Cast & Crew". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ "How to Marry a Millionaire". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ^ "How to Marry a Millionaire (1953): Track List". Film Score Monthly. Retrieved October 13, 2014.

- ^ "How to Marry a Millionaire (1953)". soundtrackinfo.com. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- ^ Schwarz, Ted (2008). Marilyn Revealed: The Ambitious Life of an American Icon. Taylor Trade Publications. p. 390. ISBN 978-1-589-79342-2.

- ^ Lev, Peter (2006). Transforming the Screen, 1950-1959. University of California Press. p. 118. ISBN 0-520-24966-6.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (November 11, 1953). "THE SCREEN: TRIO OF STARS IN CINEMASCOPE; Monroe, Grable, Bacall Illustrate 'How to Marry a Millionaire' at Globe and Loew's State Their Rich Quarry Enacted by Fred Clark, Alex D'Arcy and William Powell". The New York Times. Retrieved July 17, 2023.

- ^ "How to Marry a Millionaire | Rotten Tomatoes". www.rottentomatoes.com. Retrieved September 18, 2024.

- ^ "Oscars Ceremonies: The 26th Academy Awards - 1954: Winners & Nominees - Costume Design (Color)". Oscars. October 4, 2014. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

- ^ "BAFTA Awards Search: 1955". bafta.org. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

- ^ "Writers Guild of America, USA: Awards for 1954". IMDb. Retrieved November 10, 2014.

- ^ Siegel, Tatiana. The Hollywood Reporter 2007-04-27

Bibliography

edit- Solomon, Aubrey (1989). Twentieth Century Fox: A Corporate and Financial History. The Scarecrow Filmmakers Series. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-4244-1.

External links

edit- How to Marry a Millionaire at IMDb

- How to Marry a Millionaire at AllMovie

- How to Marry a Millionaire at Rotten Tomatoes

- How to Marry a Millionaire at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- How to Marry a Millionaire at the TCM Movie Database

- Listing of CD and LP releases of music from the film, including "Street Scene"