Heparanase, also known as HPSE, is an enzyme that acts both at the cell-surface and within the extracellular matrix to degrade polymeric heparan sulfate molecules into shorter chain length oligosaccharides.[5][6]

Synthesis and structure

editThe protein is originally synthesised in an inactive 65 kDa proheparanase form in the golgi apparatus and transferred to late endosomes/lysosomes for transport to the cell-surface. In the lysosome it is proteolytically processed into its active form. Proteolytic processing results in the production of three products,

- a linker peptide

- an 8 kDa proheparanase fragment and

- a 50 kDa proheparanase fragment

The 8 kDa and 50 kDa fragments form a heterodimer and it is this heterodimer that constitutes the active heparanase molecule.[7] The linker protein is so called because prior to its excision it physically links the 8 kDa and 50 kDa proheparanase fragments. Complete excision of the linker peptide appears to be a prerequisite to the complete activation of the heparanase enzyme.

Crystal structures of both proheparanase and mature heparanase are available, showing that the linker peptide forms a large helical domain which blocks heparan sulfate molecules from interacting with heparanase.[8] Removal of the linker reveals an extended cleft on the enzyme surface, which contains the heparanase active site.[9]

Function

editHeparanase has endoglycosidase activity and cleaves polymeric heparan sulfate molecules at sites which are internal within the polymeric chain.[10] The enzyme degrades the heparan sulfate scaffold of the basement membrane and extracellular matrix. It is also associated with the inflammatory process, by allowing the extravasation of activated T lymphocytes.[11] In ocular surface physiology this activity functions as an off/on switch for the prosecretory mitogen lacritin. Lacritin binds the cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycan syndecan-1 only in the presence of active heparanase. Heparanase partially or completely cleaves heparan sulfate to expose a binding site in the N-terminal 50 amino acids of syndecan-1.[12]

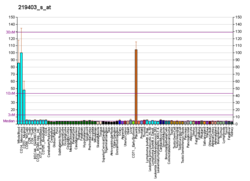

Clinical significance

editThe successful penetration of the endothelial cell layer that lines the interior surface of blood vessels is an important process in the formation of blood borne tumour metastases. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans are major constituents of this layer and it has been shown that increased metastatic potential corresponds with increased heparanase activity for a number of cell lines.[13][14] Due to the contribution of heparanase activity to metastasis and also to angiogenesis, the inhibition of heparanase activity it is considered to be a potential target for anti-cancer therapies.[15][16]

Heparanase has been shown to promote arterial thrombosis and stent thrombosis in mouse models due to the cleavage of anti-coagulant heparan sulfate proteoglycans.[17]

References

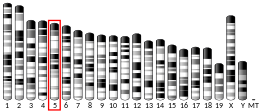

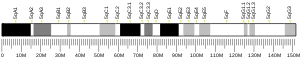

edit- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000173083 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000035273 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Vlodavsky I, Friedmann Y, Elkin M, Aingorn H, Atzmon R, Ishai-Michaeli R, Bitan M, Pappo O, Peretz T, Michal I, Spector L, Pecker I (July 1999). "Mammalian heparanase: gene cloning, expression and function in tumor progression and metastasis". Nature Medicine. 5 (7): 793–802. doi:10.1038/10518. PMID 10395325. S2CID 38895589.

- ^ Hulett MD, Freeman C, Hamdorf BJ, Baker RT, Harris MJ, Parish CR (July 1999). "Cloning of mammalian heparanase, an important enzyme in tumor invasion and metastasis". Nature Medicine. 5 (7): 803–9. doi:10.1038/10525. PMID 10395326. S2CID 20125382.

- ^ Vlodavsky I, Ilan N, Naggi A, Casu B (2007). "Heparanase: structure, biological functions, and inhibition by heparin-derived mimetics of heparan sulfate". Curr. Pharm. Des. 13 (20): 2057–2073. doi:10.2174/138161207781039742. PMID 17627539.

- ^ Wu L, Jiang J, Jin Y, Kallemeijn WW, Kuo CL, Artola M, Dai W, van Elk C, van Eijk M, van der Marel GA, Codée JDC, Florea BI, Aerts JMFG, Overkleeft HS, Davies GJ (2017). "Activity-based probes for functional interrogation of retaining β-glucuronidases" (PDF). Nat. Chem. Biol. 13 (8): 867–873. doi:10.1038/nchembio.2395. PMID 28581485.

- ^ Wu L, Viola CM, Brzozowski AM, Davies GJ (2015). "Structural characterization of human heparanase reveals insights into substrate recognition". Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 22 (12): 1016–1022. doi:10.1038/nsmb.3136. PMC 5008439. PMID 26575439.

- ^ Pikas DS, Li JP, Vlodavsky I, Lindahl U (1998). "Substrate specificity of heparanases from human hepatoma and platelets". J. Biol. Chem. 273 (30): 18770–7. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.30.18770. PMID 9668050.

- ^ Irony-Tur-Sinai, Michal; Vlodavsky, Israel; Ben-Sasson, Shmuel A; Pinto, Florence; Sicsic, Camille; Brenner, Talma (2003-01-15). "A synthetic heparin-mimicking polyanionic compound inhibits central nervous system inflammation". Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 206 (1): 49–57. doi:10.1016/S0022-510X(02)00318-0. ISSN 0022-510X. PMID 12480085. S2CID 46339755.

- ^ Ma P, Beck SL, Raab RW, McKown RL, Coffman GL, Utani A, Chirico WJ, Rapraeger AC, Laurie GW (September 2006). "Heparanase deglycanation of syndecan-1 is required for binding of the epithelial-restricted prosecretory mitogen lacritin". The Journal of Cell Biology. 174 (7): 1097–106. doi:10.1083/jcb.200511134. PMC 1666580. PMID 16982797.

- ^ Nakajima M, Irimura T, Nicolson GL (1988). "Heparanases and tumor metastasis". J. Cell. Biochem. 36 (2): 157–167. doi:10.1002/jcb.240360207. PMID 3281960. S2CID 9743270.

- ^ Vlodavsky I, Goldshmidt O, Zcharia E, Atzmon R, Rangini-Guatta Z, Elkin M, Peretz T, Friedmann Y (2003). "Mammalian heparanase: involvement in cancer metastasis, angiogenesis and normal development". Seminars in Cancer Biology. 12 (2): 121–9. doi:10.1006/scbi.2001.0420. PMID 12027584.

- ^ Yang, Jian-min; Wang, Hui-ju; Du, Ling; Han, Xiao-mei; Ye, Zai-yuan; Fang, Yong; Tao, Hou-quan; Zhao, Zhong-sheng; Zhou, Yong-lie (2009-01-25). "Screening and identification of novel B cell epitopes in human heparanase and their anti-invasion property for hepatocellular carcinoma". Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 58 (9): 1387–1396. doi:10.1007/s00262-008-0651-x. ISSN 0340-7004. PMC 11030199. PMID 19169879. S2CID 19074169.

- ^ Zhang, JUN; Yang, Jianmin; Han, Xiaomei; Zhao, Zhongsheng; Du, Ling; Yu, Tong; Wang, Huiju (2012). "Overexpression of heparanase multiple antigenic peptide 2 is associated with poor prognosis in gastric cancer: Potential for therapy". Oncology Letters. 4 (1): 178–182. doi:10.3892/ol.2012.703. PMC 3398369. PMID 22807984. Retrieved 2016-03-29.

- ^ Baker AB, Gibson WJ, Kolachalama VB, Golomb M, Indolfi L, Spruell C, Zcharia E, Vlodavsky I, Edelman ER (2012). "Heparanase regulates thrombosis in vascular injury and stent-induced flow disturbance". J Am Coll Cardiol. 59 (17): 1551–60. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.11.057. PMC 4191917. PMID 22516446.

Further reading

edit- Zcharia E, Metzger S, Chajek-Shaul T, Friedmann Y, Pappo O, Aviv A, Elkin M, Pecker I, Peretz T, Vlodavsky I (2002). "Molecular properties and involvement of heparanase in cancer progression and mammary gland morphogenesis". Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia. 6 (3): 311–22. doi:10.1023/A:1011375624902. PMID 11547900. S2CID 13292455.

- Vlodavsky I, Abboud-Jarrous G, Elkin M, Naggi A, Casu B, Sasisekharan R, Ilan N (2006). "The impact of heparanese and heparin on cancer metastasis and angiogenesis". Pathophysiol. Haemost. Thromb. 35 (1–2): 116–27. doi:10.1159/000093553. PMID 16855356. S2CID 25204783.

- van den Hoven MJ, Rops AL, Vlodavsky I, Levidiotis V, Berden JH, van der Vlag J (2007). "Heparanase in glomerular diseases". Kidney Int. 72 (5): 543–8. doi:10.1038/sj.ki.5002337. PMID 17519955.

- Maruyama K, Sugano S (1994). "Oligo-capping: a simple method to replace the cap structure of eukaryotic mRNAs with oligoribonucleotides". Gene. 138 (1–2): 171–4. doi:10.1016/0378-1119(94)90802-8. PMID 8125298.

- Suzuki Y, Yoshitomo-Nakagawa K, Maruyama K, Suyama A, Sugano S (1997). "Construction and characterization of a full length-enriched and a 5'-end-enriched cDNA library". Gene. 200 (1–2): 149–56. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(97)00411-3. PMID 9373149.

- Vlodavsky I, Friedmann Y, Elkin M, Aingorn H, Atzmon R, Ishai-Michaeli R, Bitan M, Pappo O, Peretz T, Michal I, Spector L, Pecker I (1999). "Mammalian heparanase: gene cloning, expression and function in tumor progression and metastasis". Nat. Med. 5 (7): 793–802. doi:10.1038/10518. PMID 10395325. S2CID 38895589.

- Hulett MD, Freeman C, Hamdorf BJ, Baker RT, Harris MJ, Parish CR (1999). "Cloning of mammalian heparanase, an important enzyme in tumor invasion and metastasis". Nat. Med. 5 (7): 803–9. doi:10.1038/10525. PMID 10395326. S2CID 20125382.

- Kussie PH, Hulmes JD, Ludwig DL, Patel S, Navarro EC, Seddon AP, Giorgio NA, Bohlen P (1999). "Cloning and functional expression of a human heparanase gene". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 261 (1): 183–7. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1999.0962. PMID 10405343.

- Toyoshima M, Nakajima M (1999). "Human heparanase. Purification, characterization, cloning, and expression". J. Biol. Chem. 274 (34): 24153–60. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.34.24153. PMID 10446189.

- Dempsey LA, Plummer TB, Coombes SL, Platt JL (2000). "Heparanase expression in invasive trophoblasts and acute vascular damage". Glycobiology. 10 (5): 467–75. doi:10.1093/glycob/10.5.467. PMID 10764835.

- Dong J, Kukula AK, Toyoshima M, Nakajima M (2000). "Genomic organization and chromosome localization of the newly identified human heparanase gene". Gene. 253 (2): 171–8. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(00)00251-1. PMID 10940554.

- Hulett MD, Hornby JR, Ohms SJ, Zuegg J, Freeman C, Gready JE, Parish CR (2001). "Identification of active-site residues of the pro-metastatic endoglycosidase heparanase". Biochemistry. 39 (51): 15659–67. doi:10.1021/bi002080p. PMID 11123890.

- Ginath S, Menczer J, Friedmann Y, Aingorn H, Aviv A, Tajima K, Dantes A, Glezerman M, Vlodavsky I, Amsterdam A (2001). "Expression of heparanase, Mdm2, and erbB2 in ovarian cancer". Int. J. Oncol. 18 (6): 1133–44. doi:10.3892/ijo.18.6.1133. PMID 11351242.

- Koliopanos A, Friess H, Kleeff J, Shi X, Liao Q, Pecker I, Vlodavsky I, Zimmermann A, Büchler MW (2001). "Heparanase expression in primary and metastatic pancreatic cancer". Cancer Res. 61 (12): 4655–9. PMID 11406531.

- Sasaki M, Ito T, Kashima M, Fukui S, Izumiyama N, Watanabe A, Sano M, Fujiwara Y, Miura M (2002). "Erythromycin and clarithromycin modulation of growth factor-induced expression of heparanase mRNA on human lung cancer cells in vitro". Mediators Inflamm. 10 (5): 259–67. doi:10.1080/09629350120093731. PMC 1781717. PMID 11759110.

- Jiang P, Kumar A, Parrillo JE, Dempsey LA, Platt JL, Prinz RA, Xu X (2002). "Cloning and characterization of the human heparanase-1 (HPR1) gene promoter: role of GA-binding protein and Sp1 in regulating HPR1 basal promoter activity". J. Biol. Chem. 277 (11): 8989–98. doi:10.1074/jbc.M105682200. PMID 11779847.

- Nadav L, Eldor A, Yacoby-Zeevi O, Zamir E, Pecker I, Ilan N, Geiger B, Vlodavsky I, Katz BZ (2003). "Activation, processing and trafficking of extracellular heparanase by primary human fibroblasts". J. Cell Sci. 115 (Pt 10): 2179–87. doi:10.1242/jcs.115.10.2179. PMID 11973358.