The Hüdavendigâr Vilayet (Ottoman Turkish: ولايت خداوندگار, romanized: Vilâyet-i Hüdavendigâr)[3] or Bursa Vilayet after its administrative centre, was a first-level administrative division (vilayet) of the Ottoman Empire. At the beginning of the 20th century it reportedly had an area of 26,248 square miles (67,980 km2).[4]

| ولايت خداوندگار Vilâyet-i Hüdâvendigâr | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vilayet of the Ottoman Empire | |||||||||

| 1867–1922 | |||||||||

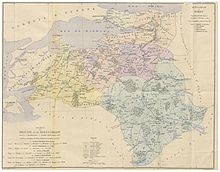

The Hüdavendigâr Vilayet in 1895 | |||||||||

| Capital | Bursa[1] | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| • Coordinates | 40°11′N 29°3′E / 40.183°N 29.050°E | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| 1867 | |||||||||

• Disestablished | 1922 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Economy

editAs of 1920, the British had described the vilayet as being "one of the most prosperous in Anatolia." The northern and western regions were mainly occupied by Christians. Highlands were populated by Turkish immigrants from Europe. The area near the Sea of Marmara was considered the most fertile area, with a large portion of the vilayet being "marshy and fever-stricken, especially between Bursa and Panderma." The Hüdavendigâr Vilayet produced wheat, barley, maize, beans, and seeds in the northern and western regions. Throughout the region, opium, tobacco and cotton was also produced. The area around Lake Iznik produced rice. The Balıkhisar area produced "some of the finest fruit grown in Turkey."[5] Barley is also of large production in the highlands and is exported to England.[5]

Silk production was considered the most valuable of the region during the 20th century. The vilayet had schools devoted to silk production. The region had obtained silkworm seed from France. Bursa was the heart of silk production.[5] The silk was mainly exported, sometimes as thread or cocoons. In the mid 19th-century, a disease spread through the silkworm, causing a decline in production. As of 1920, the disease was eradicated and business was steady. Cotton production remained steady, and towels and robes were common items produced from cotton.[6] Velvet and felt were also produced. Felt was used for saddles and other equestrian related goods. The area also made tanned leather and carpet. The city of Kütahya created tiling and pottery. Soap and flour was also produced in the vilayet.[7]

Lignite was being mined in the area between Kirmasti (today Mustafakemalpaşa) and Mihaliç (today Karacabey). Towards the end of World War 1, the region was exporting approximately 300 tons of lignite monthly to Istanbul.[8] Chromite, mercury, marble, fuller's earth, and antimony were also plentiful in the region in the early 20th century.[9][10][11]

Environmental history

editThe region was described as having "beautiful forests" in the 1920s, estimating 23,000 square kilometers. The area of Ainegeul was described by the British as having the "richest" timber. Gediz had a large oak population. The vilayet in general had tree populations consisting of fir, oak, elm, chestnut, beech, and hornbeam.[12]

Administrative divisions

editSanjaks of the Vilayet:[13]

- Sanjak of Bursa (Bursa, Gemlik, Pazarköy, Mihalıç, Mudanya, Kirmastı, Atranos)

- Sanjak of Ertuğrul (Bilecik, Söğüt, İnegöl, Yenişehir)

- Sanjak of Kütahya; belonged to Hüdavendigar Vilayet from 1867, became an independent Sanjak on 4 April 1915 after the Second Constitutional Era.[14] (Kütahya, Eskişehir (Became a sanjak centre on 14 April 1910 in Hudâvendigar Vilayet with kazas of Mahmudiye and Seyitgazi),[15] became an independent sanjak on 4 April 1915[16]), Uşak, Simav, Gediz)

- Sanjak of Karahisar-ı Sahip (Became an independent sanjak on 4 April 1915; Afyonkarahisar, Sandıklı, Aziziye, Bolvadin,[17] Dinar (It was part of Sandıklı till 1908), Çivril (It was part of Sandıklı till 1908, then Dinar between 1908 and 1910))

- Sanjak of Karesi (Balıkesir, Edremit, Erdek, Ayvalık, Balya, Bandırma, Burhaniye, Sındırgı, Gönen)

References

edit- ^ First encyclopaedia of Islam: 1913-1936, p. 768, at Google Books By M. Th Houtsma

- ^ "1914 Census Statistics" (PDF). Turkish General Staff. pp. 605–606. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ^ Salname-yi Vilâyet-i Hüdavendigâr ("Yearbook of the Vilayet of Hüdavendigar"), Hüdavendigar vilâyet matbaası, [Bursa], 1296 [1878]. in the website of Hathi Trust Digital Library.

- ^ Asia by A. H. Keane, page 459

- ^ a b c Prothero, G.W. (1920). Anatolia. London: H.M. Stationery Office.

- ^ Prothero, G.W. (1920). Anatolia. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p. 109.

- ^ Prothero, G.W. (1920). Anatolia. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p. 110.

- ^ Prothero, G.W. (1920). Anatolia. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p. 101.

- ^ Prothero, G.W. (1920). Anatolia. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p. 103.

- ^ Prothero, G.W. (1920). Anatolia. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p. 106.

- ^ Prothero, G.W. (1920). Anatolia. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p. 107.

- ^ Prothero, G.W. (1920). Anatolia. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p. 97.

- ^ Hudâvendigar Vilayeti | Tarih ve Medeniyet

- ^ "History of Kütahya". Kütahya Special Provincial Administration. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2013.

- ^ "Administrative Apprehensions in the Ottoman Provinces: The Civil-Administrative Demands and Attempts for Change in the Uşak District (1908-1919)" (PDF) (in Turkish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-06-02.

- ^ "Eskisehir Rehberi" (PDF) (in Turkish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-05-12. Retrieved 2015-05-19.

- ^ "VĠLÂYET SÂLNÂMELERĠNDE AFYONKARAHĠSAR" [AFYONKARAHİSAR IN PROVINCIAL YEARNAMES] (PDF) (in Turkish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-26. Retrieved 2015-05-19.

External links

edit- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Media related to Vilayet of Hüdavendigâr at Wikimedia Commons