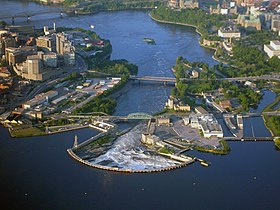

The Chaudière Falls, also known as the Kana:tso or Akikodjiwan Falls, are a set of cascades and waterfall in the centre of the Ottawa-Gatineau metropolitan area in Canada where the Ottawa River narrows between a rocky escarpment on both sides of the river. The location is just west of the Chaudière Bridge and Booth-Eddy streets corridor, northwest of the Canadian War Museum at LeBreton Flats and adjacent to the historic industrial E. B. Eddy complex. The islands surrounding the Chaudière Falls, counter-clockwise, are Chaudière Island (immediately to the South & East of the falls), Albert Island (to the South), little Coffin Island was just south of Albert Island but is now submerged, Victoria Island and Amelia Island, (which was separated from Victoria Island in 1836 by Government timber slide; now fused to Victoria Island), Philemon Island (to the North) was originally called the Peninsular Village by the Wrights but became an island when the timber slide was built in 1829 [1][2][3](some maps identify it as Wright Island, but that is incorrect) it is now fused to south shore of City of Gatineau, and Russell Island, now submerged, was at the head of the Falls before the Ring dam was built.[4] The falls are about 60 metres (200 ft) wide and drop 15 metres (49 ft). The area around the falls was once heavily industrialized, especially in the 19th century, driving growth of the surrounding cities.[5]

| Chaudière Falls | |

|---|---|

| |

Chaudière Falls in June 2006, at summer water levels | |

| |

| Location | Ottawa-Gatineau, Ontario and Quebec, Canada |

| Coordinates | 45°25′14″N 75°43′20″W / 45.42056°N 75.72222°W |

| Total height | 15 metres (49.2 ft) |

| Total width | 60 metres (197 ft) |

| Watercourse | Ottawa River |

The damming of the river and the presence of industry have greatly altered the lands surrounding the waterfall, and the fall's appearance. This is especially true in the summer when the Ottawa River is low, and the falls all but disappear because the water is diverted to power stations owned and operated by Portage Power, an affiliate of Hydro Ottawa.[6] Inaccessible for generations, the Falls and hydro facilities are now publicly accessible since the opening of Chaudiere Falls park in 2017, designed by architect Douglas Cardinal.[7] Other properties adjacent to the Falls are slated for development by public and private interests, including an Indigenous welcome centre on Victoria Island, led by the National Capital Commission (NCC) with regional First Nation representatives, and Zibi, a private mixed-use redevelopment project.

Naming

editThe "Chaudière" name was given to the falls by Samuel de Champlain, an early French explorer who noted in a 1613 journal entry that the Indigenous word for the falls was Asticou meaning boiler, but 'Asticou' is now thought to be a misprint as the Algonquin (Anishinaabemowin) word for boiler/cauldron is Akikok, and an Algonquin name for the location is Akikodjiwan.[8] The European name comes from the French Chutes de la Chaudière, meaning "Cauldron Falls", historically translated as "Kettle Falls". The shape of the falls before its development resembled a large kettle, better known to today's English speakers as a cauldron.

William S. Hunter Jr. suggested a different origin for the name in 1855: "The Word Chaudiere is the literal translation into French of the Indian word Kanajo (The Kettle), and is . . . vastly suggestive, for the chasm into which the waters of the Ottawa (Ottawa River) discharge themselves is not unlike a kettle in shape, while the seething and frothing of the surface, in its continual whirl, assists in completing the resemblance," though Hunter himself provides no reference, historical or otherwise, to contradict de Champlain's account of the naming of the falls.[9]

From a 1909 publication, sourced on the Canadian National Museum of History's website: "While waiting thus for their prey to break cover, from up or down the river, they devoted their spare time to various occupations. To the oki, whose thunderous voice was heard in the roar of the falls, they made sacrifices of tobacco; while the Mohawks and Onondagas each gave a name to that cauldron of seething water which is known to us as The Big Kettle. The Mohawks called it Tsitkanajoh, or the Floating Kettle, while the Onondagas named it Katsidagweh niyoh or Chief Council Fire. It is possible that our Big Kettle may be a modified or corrupted translation of the Mohawk term."[10]

Akikodjiwan is the name given to the falls by some Anishinaabe peoples of this area. For Anishinaabe who gathered and traded along portage routes surrounding the Falls, the waterfall's whirlpool was the bowl of a great peace pipe, and its mists were smoke rising to the Creator.[11]

History

editPre-contact Indigenous trade and travel

editPrior to European contact and colonization, the area surrounding the Chaudière Falls and islands was a significant meeting place between peoples in the region. Hunting grounds and temporary or semi-permanent settlements dotted the banks of the Ottawa River (Kichi Sipi), as rivers and waterways were used as highways,[12] thanks to innovations such as the canoe. Water levels around the Chaudiere Falls would fluctuate 28 feet (8.5 m) throughout the year, depending on rain and snow melts, and would flood the islands and large swaths of land throughout the watershed. The primary inhabitants of the region were the Algonquin Anishinaabe, who carved complex networks of portage routes to circumvent waterfalls and other natural landmarks.

Exploration and the fur trade

editSamuel de Champlain is the first recorded European to label the falls, chaudière, (which the English for a time would call 'Big Kettle')[13] during his 1613 voyage along the Ottawa River. Champlain describes in his journal on June 14, 1613:

- "At one place the water falls with such violence upon a rock, that, in the course of time, there has been hollowed out in it a wide and deep basin, so that the water flows round and round there and makes, in the middle, great whirlpools. Hence, the savages call it Asticou, which means kettle. This waterfall makes such a noise that it can be heard for more than two leagues off.[14]"

- "After having carried their canoes to the foot of the falls, they assembled at one place where one of them with a wooden plate takes up a collection, and each one of them places in this plate a piece of tobacco… the plate is placed in the middle of the group, and all dance about it, singing in their fashion; then one of the chiefs makes a speech, pointing out that for a long time they have been accustomed to making this offering, and that by this means they are protected from their enemies…the speaker takes the plate and throws the tobacco into the middle of la chaudière [kettle] and they make a great cry all together."[15] As a medicine plant, the use of tobacco in this Indigenous ceremony signifies that the falls were made a sacred offering.

In the days of the fur trade, the Chaudière Falls were an obstacle along the Ottawa River trade route. Canoes were portaged around the falls at the place now known as Hull.

European colonization

editThe arrival of Philemon Wright to this area in 1800 marked the start of the development of the city of Hull. In 1827, the region's first bridge, Union Bridge was built close to the falls.[16] When the logging industry began in this area and farther upstream, the falls were again an obstacle for log driving. In 1829, Ruggles Wright (son of Philemon Wright) built the first timber slide, allowing logs and timber rafts to bypass the falls along the north shore, along what is now known as rue Laurier[17] in Gatineau. In 1836, George Buchannan built a slide for cribs between Victoria and Chaudière Islands (on the south side of the river) which later became a major tourist attraction where King Edward VII (then Prince Albert of Wales) in 1860, and the future George V in 1901 both experienced the thrill of "shooting the slides".[18]

Also in the 19th century, some of Canada's largest sawmills were located near the falls. Notable lumber barons in this area were Henry Franklin Bronson and John Rudolphus Booth.

Since then, all the islands and shores at the Chaudière Falls have been developed and the river's flow and drop have long been harnessed to operate paper mills and power stations. In 1910, the ring dam that diverts water to the power stations was built.[19] The E. B. Eddy Company operated a matchmaking business, and a variety of pulp and paper mills, later acquired by Montreal-based Domtar Inc. in 1998. Operations ceased in 2007,[20] the majority of the private properties put up for sale, and transfer to Hydro Ottawa and Hydro-Québec to operate run-of-the-river hydro-electric generating stations at the falls.

Victoria Island

editVictoria Island (45°25′16″N 75°42′44″W / 45.421151°N 75.712228°W) is located in Ontario between Ottawa and Gatineau on the Ottawa River, where it narrows near the Canadian War Museum at LeBreton Flats. The island is accessible via the Chaudière Bridge, which connects Ottawa's Booth Street to Rue Eddy in Gatineau; the Portage Bridge connecting the two cities passes over. The island had been used by First Nations people for centuries, who named the area Asinabka (Place of Glare Rock). According to archaeological evidence, this site was the centre of convergence for trade and spiritual and cultural exchange. Its position—at the meeting place of three rivers and perched on a rocky point overlooking fast-moving water—gave it special meaning.[21] It is currently part of an area administered by the National Capital Commission.

The island contains an Indigenous business, "Aboriginal Experiences", which offers the history of the First Nations people, a tour, traditional dance, a cafe, and a First Nations craft workshop, all in a wood-pole-fence enclosed area.[22] In 2012, it was selected as the site of Attawapiskat Chief Theresa Spence's protest, due to its proximity to Parliament Hill and its significance to Aboriginal peoples.[23]

Inspired by Algonquin chief and elder William Commanda's vision for Asinabka (the traditional Algonquin Anishinabe name Commanda held for the site), and of a Circle of All Nations and the 8th Fire Prophecy, world-renowned architect Douglas Cardinal has designed plans for an aboriginal healing and international peacekeeping centre on the site. Although there is general consensus for the developments on Victoria Island, while some dispute Commanda's vision for the other islands and falls, his full vision is documented in a presentation he made to the City of Ottawa in 2010[24] and is also more extensively documented on the Asinabka.com website.[25]

Victoria Island contains the following buildings: Aboriginal Experiences Centre, the Ottawa Electric Railway Company Steam Plant, the Bronson Company Office, No. 4 Generating Station, the Wilson Carbide Mill and Ottawa Hydro Generating Station #2.

On October 3, 2018, the National Capital Commission (NCC) announced that it would be closing down all access to the island, including its businesses, for remediation work from December 2018 to Spring 2020.[26] A second remediation phase is proposed to be undertaken between 2020 and 2025.

Zibi development project

editZibi is a 34 acres (14 ha) mixed-use development started by Windmill Development Group, later joined by a larger development company, DREAM Unlimited Corporation, and then spun off from Windmill with a new company named Theia Partners, that includes residential, commercial, retail, office and hotel spaces, being built on the northern riverbank in Gatineau, and on Chaudiere and Albert Islands in Ottawa. The 15-year redevelopment will repurpose the existing E. B. Eddy buildings and build new developments adjacent to the Falls. It will be home to approximately 3,500 residents when completed.[27] The redevelopment is opposed by groups and individuals hoping to restore the site to a natural state and return the unceded area to Algonquin stewardship.[28]

Windmill named the project "Zibi", the Algonquin Anishinabe word for river,[29] following a public naming competition. Patrick Henry, who entered the winning suggestion, declined the prize and asked that the money go to a canoe trip involving Kitigan Zibi youth instead, but the youth then asked that they not accept the money. Speaking personally, the then-Chief of Kitigan Zibi Gilbert Whiteduck confirmed having had several respectful discussions with the company representatives but stated they did not consult with Algonquin Elders, nor follow proper protocols.[30] The company alleges the name was chosen to celebrate the significant waterways in the region, and bring attention to the Algonquin Nation's traditional territory in Eastern Ontario and Western Quebec.

Since 2015, the First Nation partners of the project are the Algonquins of Pikwàkanagàn First Nation, and the Algonquins of Ontario (AOO), representing 10 communities, including Pikwakanagan. The AOO is the only named Algonquin Aboriginal Interest in the City of Ottawa's official plan (section 5.6).[31] In April 2017, two more communities signed Letters of Intent with the development, Long Point First Nation and Timiskaming First Nation.[32] These communities are working with the developers towards tangible benefits such as long-term employment and job training, investment opportunities, residential and commercial ownership, public art, and tangible recognition of Algonquin Anishinabe traditional territory.[33][34] According to Windmill, they have made efforts since 2013 to change the traditional relationship between First Nation communities and private development, and have engaged sincerely and meaningfully with all Algonquin Anishinabe communities[35] in Ontario and Quebec, and several tribal Councils.

All but one of the ten status Algonquin communities opposed the Zibi project,[36] although as noted above, two of those communities shifted their position.[37][38] "Free The Falls"[39] formed to support the Ontario Municipal Board appeal of the city's rezoning of the site as well as to support the Asinabka vision. Chaudière and Albert Islands to their natural state, and is collecting signatures on a petition to that end.[40] This non-Indigenous group views it as an example of cultural appropriation, "red-washed commercial exploitation", and a violation of Indigenous Rights as per the UNDRIP. They disagree with the development because they believe that the islands around the falls have been a sacred religious site for millennia, and would prefer to see all islands turned into public parkland and Indigenous site as per the 1950s NCC plans, the Asinabka vision led by the late Algonquin leader William Commanda,[41] and the AFN resolution of December 2015. Other notable project opponents include Indigenous architect Douglas Cardinal[42] and author John Ralston Saul.[43]

For Algonquin communities that are partners to the project, non-Indigenous interventions in Zibi have been an issue in advancing economically in the region. Chief Kirby Whiteduck of Pikwakanagan stated that "The Algonquin people don't need to be saved from the Zibi project".[44] Others such as Albert Dumont from Kitigan Zibi reproach the project's leadership for being non-Indigenous.[45] Discussions with several other Algonquin communities are ongoing with the developers.

Hydroelectric power generation

editCentrale Hull 2

editCentrale Hull 2 is a 27 MW 4-turbine hydroelectric generating station on the Ottawa River on the Gatineau side of the Chaudière Falls (45°25′17″N 75°43′11″W / 45.42143°N 75.719728°W). It is owned by Hydro-Québec and is listed as a run-of-the-river dam and its commission date as 1920–1969.[46] Its reservoir capacity is 4 million cubic metres (140 million cubic feet).[47]

The station was originally built in 1912-1913 for the Gatineau Power Company by William Kennedy Jr. but did not begin operating until 1920, following World War I, when it had two turbines in operation. A third turbine was added in 1923. In 1965, Gatineau Power was sold to Hydro-Québec, which added a fourth turbine in 1968.[48]

Chaudière Falls Generating Stations

editHydro Ottawa operates two run-of-the-river hydroelectric generating stations without a dam. Generating Station 2 was built in 1891 and is leased from the National Capital Commission. Generating Station No. 4 was built in 1900 and is operated on land owned by the Government of Canada. The combined output is around 110 GWh per year [values not credible].[49]

The stations were refurbished in the 2000s, including a small capacity increase in 2007. Hydro Ottawa purchased the site around the falls from Domtar Corporation in 2012, including the ring dam and water rights.[50] A project started in 2015 and completed in 2017 increased the generating capacity of the stations from 29 to 58 MW.[19] This project buried new turbines below grade next to the falls, enabling public access, new viewing platforms and a park celebrating Algonquin and industrial heritages.[51]

See also

editReferences

edit- Bibliography

- Fodor's Travel (2008), Fodor's Canada, 29th Edition, Fodor's Travel, ISBN 978-1-4000-0734-9

- Haig, Robert (1975), Ottawa: City of the Big Ears, Ottawa: Haig and Haig Publishing Co., OCLC 9184321

- Mika, Nick & Helma (1982), Bytown: The Early Days of Ottawa, Belleville, Ont: Mika Publishing Company, ISBN 0-919303-60-9

- Woods, Shirley E. Jr. (1980), Ottawa: The Capital of Canada, Toronto: Doubleday Canada, ISBN 0-385-14722-8

- Notes

- ^ Geological Survey of Canada, Multicoloured Geological Map 714, 1901, 1 sheet, https://doi.org/10.4095/107537

- ^ http://geo-outaouais.blogspot.com/2014/06/; Released: 1901 01 01; GEOSCAN ID: 107537

- ^ Brault, Lucien. Hull 1800-1950. Ottawa: Les Éditions de l'Université d'Ottawa, 1950, p. 133

- ^ Map of the City of Ottawa, P. Ontario, and the City of Hull, P. Quebec, and their adjacent suburbs. Compiled by John A. Snow and Son. Provincial Land Surveyors and C.E.ng's. From Surveys and Official Records. Scale 660 feet to One Inch. [1895] Found on http://geo-outaouais.blogspot.com/2014/06/

- ^ "How the Ottawa River made Canada's capital what it is today". August 19, 2016.

- ^ "Chaudière Falls Expansion". energyottawa.com.

- ^ "Chaudière Falls". chaudierefalls.com.

- ^ Ottawa River Heritage Designation Committee. "A Background Study for Nomination of the Ottawa River Under the Canadian Heritage Rivers System" (PDF). Ottawa Riverkeeper. QLF Canada. p. Numbered 22 (but is 37 of the pdf).

- ^ Hunter Jr., William S (1855). Ottawa's Scenery in the Vicinity of Ottawa City, Canada. Ottawa, ON: Nabu Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-1272010157.

- ^ Sowter, T. W. Edwin (1909). "Algonkin and Huron occupation of the Ottawa Valley". The Ottawa Naturalist. Ottawa, Ontario. Vol. XXIII, No. 4: 61-68 & Vol. XXIII, No. 5:92-104

- ^ "Crawford Purchase". The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- ^ walker (June 28, 2018). "Mapping the Ottawa River, the "original Trans-Canada Highway"".

- ^ Haig 1975, p. 42.

- ^ Woods 1980, p. 6.

- ^ "About: The Falls". Free The Falls.

- ^ Mika 1982.

- ^ "Rue Laurier". Rue Laurier.

- ^ Mika 1982, pp. 121, 122.

- ^ a b Willems, Steph (March 13, 2014). "Chaudiere Falls hydro generating station to expand". Ottawa West News EMC. p. 7.

- ^ "Domtar to close historic Gatineau mill, Ottawa plant". CBC News.

- ^ Canadian House of Commons. "Report to Canadians 2008" (PDF). Parliament of Canada. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 6, 2012. Retrieved October 26, 2011.

- ^ Fodor's Travel 2008.

- ^ "Idle No More protests continue as minister urges Theresa Spence to end strike". National Post. December 28, 2012. Retrieved May 14, 2016.

- ^ "A report on the vision for the Asinabka national indigenous centre". City of Ottawa. Retrieved September 22, 2017.

- ^ "Home page". Asinabka. Circle of All Nations.

- ^ Commission, National Capital (November 6, 2018). "NCC progressively closing Victoria Island for site remediation - National Capital Commission". National Capital Commission. Archived from the original on October 26, 2018. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- ^ "Home". Zibi. Retrieved December 12, 2018.

- ^ "Resolutions - Special Chiefs' Assembly of December 2015" (PDF). Assembly of First Nations. pp. 16–19 of PDF file.

- ^ "Welcome to 'Zibi': Windmill launches Albert, Chaudière islands development (with video)". Ottawa Citizen. February 25, 2015. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- ^ "Kitigan Zibi chief says he won't support Windmill development". Ottawa Citizen.

- ^ Planning, Infrastructure & Economic Development Dept (October 18, 2017). "Section 5 - Implementation". ottawa.ca. Retrieved December 12, 2018.

- ^ "2 Quebec Algonquin communities back controversial Zibi development". CBC. Retrieved September 22, 2017.

- ^ "Windmill vows jobs and collaboration with Algonquin on 'Zibi' development". Ottawa Citizen. May 21, 2015. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- ^ "Collaboration & Reconciliation – Zibi Dialogue". www.zibidialogue.com. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- ^ "Consultation & Consent – Zibi Dialogue". www.zibidialogue.com. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- ^ "Algonquin chiefs pass resolution to protect sacred land at Chaudière Falls". rabble.ca.

- ^ "Kitigan Zibi chief says he won't support Windmill development". Ottawa Citizen. Retrieved September 22, 2017.

- ^ "AFN Resolution re Akikodjiwan" (PDF). Paragraph "M": AFN. December 2015. p. 3.

- ^ "Free The Falls". freethefalls.ca.

- ^ "Petition to stop Zibi comes before more condos hit market". CBC News. November 2, 2015. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- ^ "The Legacy Vision of William Commanda for The Sacred Chaudiere Site and The Indigenous Centre at Victoria Island".

- ^ Cardinal, Douglas (August 19, 2016). "Douglas Cardinal: When condos speak louder than words, and the battle for Chaudière falls". Ottawa Citizen. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

Zibi, using the Algonquin word for River, is a red-washed commercial exploitation, which further insults, disrespects and abuses that which is sacred to us.

- ^ Spears, Tom (November 3, 2015). "Algonquins protest Windmill Development's Chaudière plan". Ottawa Citizen. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

I don't understand why land which was zoned park was so rapidly rezoned for condos and commerce in the centre of the national capital, and more important at the centre of William Commanda's dream.

- ^ "Kirby Whiteduck: The Algonquin people don't need to be saved from the Zibi project". Ottawa Citizen. August 14, 2015. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- ^ Dumont, Albert. "In Defence of Indigenous Spiritual Beliefs".

- ^ "Hydroelectric generating stations". Hydro-Québec. January 1, 2016. Retrieved May 14, 2016.

- ^ "Details". August 18, 2008. Archived from the original on May 31, 2016. Retrieved May 14, 2016.

- ^ "Architecture of Old Hull - Power Plant - History". Retrieved May 14, 2016.

- ^ "Generating Stations". Archived from the original on September 17, 2006. Retrieved September 21, 2006. [the citation does confirm the referenced value, but the numbers are not credible when compared to other power generating facilities; Niagara Falls, e.g., claims a lower output.

- ^ Porter, Kate (November 26, 2015). "Hydro Ottawa's new power plant to open view of Chaudière Falls". CBC. Retrieved July 20, 2016.

- ^ "Chaudière Falls". Retrieved December 12, 2018.