Fort Hunter Liggett is a United States Army post in Jolon, California, in southern Monterey County, California. The fort, named in 1941 after General Hunter Liggett, is primarily used as a training facility, where activities such as field maneuvers and live fire exercises are performed. It is roughly 25 miles northwest of Camp Roberts, California.

| Fort Hunter Liggett | |

|---|---|

| Monterey County, California, USA | |

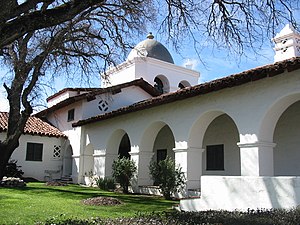

A public hotel within Fort Hunter Liggett | |

| Coordinates | 35°57′08″N 121°13′50″W / 35.952226°N 121.23065°W[1] |

| Type | Training Reservation/military base |

| Site information | |

| Owner | |

| Controlled by | IMCOM-Readiness |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Active, in use |

| Website | home |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1940 |

| In use | 1940–Present |

| Garrison information | |

| Current commander | Col. Stephen S. Trotter |

| Garrison | 80th Division (IT) 91st Training Division (Operations) |

Geography

editThe Salinas Valley is the fort's northern border, the Santa Lucia Mountains bound it on the east, Los Padres National Forest on the west and the Monterey and San Luis Obispo County line on the south. The fort originally comprised 200,000 acres (81,000 hectares), but even at its present size of 167,000 acres (68,000 hectares), it is the largest United States Army Reserve post.

Some of the land, 52 acres (21 hectares), was given to Mission San Antonio de Padua, bringing its size to 85 acres (34 hectares). Additionally, land has been traded between the United States Forest Service, which owns the adjacent Los Padres National Forest, and the Army. Junipero Serra Peak is to the north and Bald Mountain to the south. The fort also contains the headwaters of the Nacimiento River and San Antonio River. The opening helicopter scene of We Were Soldiers was filmed at the old Bailey Bridge spanning the Nacimiento River.

There is an historic hotel on the Post known as The Hacienda (Milpitas Ranchhouse) which serves the general public and can be used as guest housing by military personnel, and as available, to the public. The "west wing" of The Hacienda has also served as the Installation Commander's Quarters during various periods. A short distance past the old main gate, there is a road to the southwest which goes to what is known as the "Primitive Campgrounds". There are some camper trailers there, and some water spigots around the site. There is also a central restroom on the site and a store. Near that area is a lot that has several used FEMA trailers stored.

Nacimiento-Fergusson Road, which runs through the fort, is the only road that connects the Salinas Valley with Highway 1 between Cambria and Pacific Grove. However, in January 2021, several landslides have destroyed the road. Reopening is not anticipated until 2023 or 2024.

Climate

editUnder the Köppen Climate Classification, "dry-summer subtropical" climates are often referred to as "Mediterranean". This climate zone has an average temperature above 10 °C (50 °F) in their warmest months, and an average in the coldest between 18 and −3 °C (64 and 27 °F). Summers tend to be dry with less than one-third that of the wettest winter month, and with less than 30 mm (1.2 in) of precipitation in a summer month[2]

| Climate data for Fort Hunter Liggett, CA | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 58 (14) |

62 (17) |

66 (19) |

73 (23) |

78 (26) |

87 (31) |

94 (34) |

93 (34) |

89 (32) |

80 (27) |

69 (21) |

60 (16) |

76 (24) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 33 (1) |

36 (2) |

38 (3) |

41 (5) |

45 (7) |

49 (9) |

53 (12) |

52 (11) |

50 (10) |

44 (7) |

37 (3) |

33 (1) |

43 (6) |

| Average precipitation inches (cm) | 2 (5.1) |

2 (5.1) |

1.9 (4.8) |

1.2 (3.0) |

0.3 (0.76) |

0 (0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0 (0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.3 (0.76) |

1.2 (3.0) |

2.1 (5.3) |

11.1 (28) |

| Source: Weatherbase [3] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

editFort Hunter Liggett | |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | Monterey |

| Area | |

• Total | 2.810 sq mi (7.28 km2) |

| • Land | 2.779 sq mi (7.20 km2) |

| • Water | 0.031 sq mi (0.08 km2) |

| Elevation | 1,037 ft (316 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 250 |

| • Density | 89/sq mi (34/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (PDT) |

| GNIS feature ID | 2805235[5] |

The United States Census Bureau has designated Fort Hunter Liggett as a separate census-designated place (CDP) for statistical purposes, covering the fort's permanent residential population. It was first listed as a CDP in the 2020 census[6] with a population of 250.[7]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 250 | — | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[8] 1850–1870[9][10] 1880-1890[11] 1900[12] 1910[13] 1920[14] 1930[15] 1940[16] 1950[17] 1960[18] 1970[19] 1980[20] 1990[21] 2000[22] 2010[23] | |||

2020 census

edit| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2020[24] | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 123 | 49.20% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 23 | 9.20% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 3 | 1.20% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 22 | 8.80% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 9 | 3.60% |

| Other Race alone (NH) | 8 | 3.20% |

| Mixed Race or Multi-Racial (NH) | 8 | 3.20% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 54 | 21.60% |

| Total | 250 | 100.00% |

History

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2011) |

In 1923, Newhall Land sold Rancho San Miguelito de Trinidad and Rancho El Piojo to William Randolph Hearst.[25] In 1925, Hearst's Piedmont Land and Cattle Company bought Rancho Milpitas and neighboring Rancho Los Ojitos (Little Springs) ) from the James Brown Cattle Company.[26] The Hacienda, now a hotel, was constructed during Hearst's ownership and was designed by the architect Julia Morgan. The government purchased Hearst's properties plus two-thirds of Rancho Pleyto. It added other private holdings as well.[27] This surrounded the small unincorporated town of Jolon, which remains today in a significantly diminished form from its heyday.

The post is about 25 miles (40 km) southwest of King City and about 86 miles (138 km) south of old Fort Ord on the Monterey Peninsula. In general, the installation is bounded on the north by the Salinas Valley, on the east by the foothills of the Santa Lucia Mountains, on the south by the Monterey/San Luis Obispo county line and on the west by approximately 55 miles (89 km) of Los Padres National Forest. The highest mountain in the area is Junipero Serra Peak. At 5,862 feet (1,787 m), it is visible toward the north and has a fairly good road leading to the summit. The peak was formerly known as Santa Lucia and local long-time residents still call it by that name. In winter it is sometimes cloaked with a white mantle of snow.[28]

The fort is named for Lt. Gen. Hunter Liggett, a commander and chief of staff under General John J. Pershing during World War I.[27]

Fort Hunter Liggett was under the authority of Camp Roberts, California, to the southeast, until 1952, when it became a sub-installation of Fort Ord. From the 1970s through the early 1990s, the post served two purposes — as a training area for the 7th Light Infantry Division (based at Fort Ord), and as the home for the Training and Experimentation Command (USACDEC) (usually abbreviated as CDEC and later as TEC). The mission of CDEC was to evaluate new Army and Marine Corps weapons systems by providing a simulated Soviet Mechanized Rifle Company to act as the "OPFOR", or Opposing Forces. By this method, the Sgt. York anti-aircraft gun was found to have serious flaws, while the Marine's Light Armored Vehicle was validated. As of October 2018[update], the command is officially designated as the U.S. Army Garrison Fort Hunter Liggett with Parks Reserve Forces Training Area (RFTA) (aka Camp Parks) located in Dublin, California as a sub-installation. [28]

Base Realignment and Closure impact

editIn its 2005 Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) recommendations, the Department of Defense recommended relocating the 91st Division from Parks Reserve Forces Training Area to Hunter Liggett. In 2007, the Army created the Combat Support Training Center at Fort Hunter Liggett and ramped up training from roughly 300,000 man-days per year (predominately during the summer), to over 850,000 per year, year-round. While training was centered around United States Army Reserve units preparing for deployment, such was provided to all Army components (Active, Reserve, and Guard), and to Air Force, Navy, Marines, and even foreign commands (the Japanese Ground Self-Defense Force trained there in late 2007). Exercises held that first year included Pacific Warrior and Global Medic, which involved over 6,000 troops at Hunter Liggett, and connections to other units in locations across the nation. The Army installation's garrison commander relocated from Camp Parks to Hunter Liggett in early 2007, with oversight for Camp Parks and Army units and housing that remain at former NAS Moffett Field and B.T. Collins Reserve Center in Sacramento.[29]

Significant training infrastructure improvements were made including several Tactical Training Bases (TTBs - analogous to Forward Operating Bases), a wired "shoot-house", improvements to the hardened landing strip capable of handling larger Air Force transport planes, and a 7-mile live-fire convoy course, the US Army's only such training area capable of handling 360-degree fire up to .50 caliber. A new US Army Reserve Center was constructed and the 91st Division moved into their new Headquarters building in May 2009. On 11 September 2010 the new HQ was designated as the Master Sergeant Robb G. Needham Army Reserve Center after the first 91st Division combat casualty since WWII.[30][non-primary source needed]

Filming location

editFort Hunter Liggett was used to film parts of the movie We Were Soldiers.[31] The post was also used in the filming of Clear and Present Danger, starring Harrison Ford.[citation needed]

The post is featured in Road Trip with Huell Howser Episode 147.[32]

Fires

editIn 2002, a small portion of Fort Hunter Liggett was scorched by a 2,000-acre fire that was started by a U.S. Forest Service employee's personal Jeep. The fire resulted from a "mechanical failure" in the vehicle, and the employee tried to put the fire out before it spread to brush. No injuries were reported but the fire did consume several outbuildings.[33] Following the ramp-up in training in 2007, two fires that year consumed 5,000 acres (an elevated boom struck an electrical wire, sparking the fire) and 2,000 acres (sparks from live fire catching dry vegetation near by).

In 2008, negligent campers left a fire smoldering at a Los Padres National Forest campsite immediately northeast of Hunter Liggett. The ensuing wildfire — subsequently called the "Indians Fire" after the campsite where it originated — consumed over 200,000 acres, 9,000 of which were on the northern end of the military installation. While battling the fire, over 3,000 firefighters from across the nation based at Fort Hunter Liggett near one of the newly established Tactical Training Bases.

On August 13, 2016, the Chimney Fire started on the south side of Lake Nacimiento and burned northward onto the post. By the time the fire was contained, over 46,000 acres were burned of which several thousand were on the southwest part of the post.

The Dolan Fire reached Fort Hunter Liggett in September 2020, forcing an evacuation warning. The fire began in August near Limekiln State Park.[34]

Ecology

editThe fort covers hundreds of acres of grassland, chaparral and oak woodland. There are several vernal pools, a rare habitat type.[35] The entire world population of the rare Santa Lucia mint (Pogogyne clareana) occurs on Fort Hunter Liggett grounds.[36]

A herd of tule elk (Cervus canadensis nannodes) was established at Fort Hunter Liggett in December 1978 by translocation of 22 elk from the Tupman Tule Elk Reserve in Buttonwillow, California, and two additional elk bulls translocated were from San Luis National Wildlife Refuge in September 1979. However, severe poaching resulted in failure of the translocation, with 14 of 15 elk mortalities the result of illegal hunting.[37] The herd was re-established by the addition of 26 tule elk from the Owens Valley tule elk herd in December 1981, and the population reached 300-400 individual animals by 2002.[38]

Notes

edit- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Fort Hunter Liggett

- ^ "Hunter Liggett, California Köppen Climate Classification". Weatherbase. Retrieved 2014-07-20.

- ^ "Weatherbase.com". Weatherbase. 2013. Retrieved on May 1, 2013.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files - California". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ a b "Fort Hunter Liggett Census Designated Place". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ "2020 Geography Changes". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "Fort Hunter Liggett CDP, California". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 13, 2022.

- ^ "Decennial Census by Decade". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1870 Census of Population - Population of Civil Divisions less than Counties - California - Almeda County to Sutter County" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1870 Census of Population - Population of Civil Divisions less than Counties - California - Tehama County to Yuba County" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1890 Census of Population - Population of California by Minor Civil Divisions" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1900 Census of Population - Population of California by Counties and Minor Civil Divisions" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1910 Census of Population - Supplement for California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1920 Census of Population - Number of Inhabitants - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1930 Census of Population - Number and Distribution of Inhabitants - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1940 Census of Population - Number of Inhabitants - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1950 Census of Population - Number of Inhabitants - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1960 Census of Population - General population Characteristics - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1970 Census of Population - Number of Inhabitants - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1980 Census of Population - Number of Inhabitants - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1990 Census of Population - Population and Housing Unit Counts - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "2000 Census of Population - Population and Housing Unit Counts - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "2010 Census of Population - Population and Housing Unit Counts - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Fort Hunter Liggett CDP, California". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "HEARST BUYS SITE OF MISSION: 17 Miles of Conduits Constructed in 1792 on Acquired Tract". Stockton Independent. 1923-01-12. p. 4.

- ^ "Monterey County Historical Society, Local History Pages—Overview of Post-Hispanic Monterey County History". Archived from the original on 2006-05-22.

- ^ a b Raycraft, Susan; Beckett, Ann Keenan (2006). San Antonio Valley. Arcadia Publishing. p. 109. ISBN 9780738546681. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- ^ a b "The United States Army | Fort Hunter Liggett". www.liggett.army.mil. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- ^ "History of Combat Support Training Center". About CSTS. United States Army. 2008-10-08. Archived from the original on April 24, 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-16.

- ^ Hudson, Jason (12 January 2015). "Soldier Remembered at Fort Hunter Liggett". Golden Guidon. 91 st Training Division. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- ^ IMDB

- ^ "Fort Hunter Liggett – Road Trip with Huell Howser (147) – Huell Howser Archives at Chapman University".

- ^ Times Wire Report - July 13, 2002

- ^ "Dolan Fire breaches Fort Hunter Liggett, 3 firefighters injured". Paso Robles Daily News. 9 September 2020. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ "Cooperative Conservation America". Archived from the original on 2011-07-25. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- ^ "Center for Plant Conservation: P. clareana". Archived from the original on 2010-10-29. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- ^ Hanson, Michael T.; James M. Willison (1983). "The 1978 Relocation of Tule Elk to Fort Hunter Liggett - Reasons for Its Failure". Cal-Neva Wildlife Transactions: 42–49. Retrieved December 22, 2021.

- ^ "Fort Hunter Liggett Resources" (PDF). No. Winter. Techline. 2002. Retrieved December 22, 2021.

This article incorporates public domain content from United States government sources.

External links

edit- Fort Hunter Liggett homepage

- Global Security - Fort Hunter Liggett

- Howser, Huell (30 September 2009). "Fort Hunter Liggett – Road Trip (147)". California's Gold. Chapman University Huell Howser Archive. This video features many of the sites at Fort Hunter Liggett, and includes a brief interview with the Installation Commander, Col. Kevin Riedler.

- Martha Crusius (10 January 2007). "National Park Service Special Resource Study of Fort Hunter Liggett". National Park Service.