The "Fish" Cheer/I-Feel-Like-I'm-Fixin'-to-Die Rag

"I-Feel-Like-I'm-Fixin'-to-Die Rag" is a song by the American psychedelic rock band Country Joe and the Fish, written by Country Joe McDonald, and first released as the opening track on the extended play Rag Baby Talking Issue No. 1, in October 1965. "I-Feel-Like-I'm-Fixin'-to-Die Rag"'s dark humor and satire made it one of the most recognized protest songs against the Vietnam War. Critics cite the composition as a classic of the counterculture era.

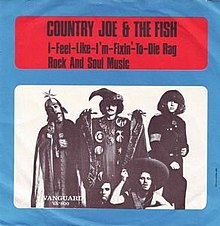

| "The 'Fish' Cheer/I-Feel-Like-I'm-Fixin'-to-Die Rag" | |

|---|---|

1968 Swedish picture sleeve | |

| Song by Country Joe and the Fish | |

| from the album I-Feel-Like-I'm-Fixin'-to-Die | |

| Released | November 1967 |

| Genre | Folk rock[1][2] |

| Length | 3:44 |

| Label | Vanguard |

| Songwriter(s) | Country Joe McDonald |

| Producer(s) | Samuel Charters |

The song was usually preceded by "The Fish Cheer", a cheer spelling out "F-I-S-H". An altered version of the cheer that was performed in live performances, known as "The Fuck Cheer", resulted in a television ban for Country Joe and the Fish in 1968, for the vulgarity, but was applauded by concert-goers.

"I-Feel-Like-I'm-Fixin'-to-Die Rag" saw a more commercial release on the group's second album, I Feel Like I'm Fixin' to Die, which was distributed in November 1967. Released as a single in 1969, this version reached number one on Tio i Topp in Sweden. The song was a favorite among the hippie culture, and was featured in McDonald's set list at the Woodstock Festival in 1969. Decades later, McDonald had a lawsuit filed against him for allegedly infringing on the copyright of Kid Ory's tune, "Muskrat Ramble". McDonald denied these allegations and the suit was later dismissed.

History

editComposition and Rag Baby

editAlthough the song achieved national notoriety when it was included on Country Joe and the Fish's second album, I Feel Like I'm Fixin' to Die, it was first composed and distributed two years prior.[3] In 1965, Country Joe McDonald founded and edited for a local counterculture magazine in Berkeley, California, which he called Rag Baby – a Bay Area adaptation of the folk magazine Broadside. McDonald published four editions of the magazine, and sought to incorporate musical influences to support Rag Baby's left-wing message.[4] To accommodate the issue, McDonald was inspired to distribute a "talking issue" of the magazine, an extended play called Rag Baby Talking Issue No. 1. In June 1965, an early incarnation of Country Joe and the Fish recorded an acoustic version of "I-Feel-Like-I'm-Fixin'-to-Die Rag", the later debut album track, "Superbird", and two other songs by local folk musician, Peter Krug at Arhoolie Records Studios, under the guidance of record producer Chris Strachwitz.[5] According to McDonald, the rag was written in under 30 minutes with a conscious purpose of reflecting on the escalation of the Vietnam War, while he composed another song, "Who Am I", which was also relating to the US's increasing armed involvement.[6] About 100 copies of the EP were pressed on McDonald's independent label and, were sold at Sproul Plaza in UC Berkeley, during a Teach-in, and in underground stores that stocked Rag Baby.[4]

The song's lyrics implicitly blame American politicians, high-level military officers, and industry corporations on starting the Vietnam War. McDonald composed "I-Feel-Like-I'm-Fixin'-to-Die Rag" in the summer of 1965, just as the U.S.'s military involvement was increasing, and was intensively opposed by the young generation.[6] It expresses discontent towards the process of conscription, through the use of dark humor, and culminating in a reflection of casualties of the war, as hinted in the satirical invitation to "be the first one on your block, to have your boy come home in a box". In addition, the song features a signature chorus:

And it's one, two, three, what are we fighting for?

Don't ask me I don't give a damn

Next stop is Vietnam.

And it's five, six, seven, open up the pearly gates,

Well there ain't no time to wonder why,

Whoopie! We're all gonna die![7]

The album version concludes with the uttering of several light machine guns firing and a final explosion, evoking the dropping of another atomic bomb.[8]

Album version and "The Fuck Cheer"

editAfter a brief stint performing as a duo in Berkeley, McDonald and Barry Melton recruited more members and eventually signed a recording contract with Vanguard Records in December 1966.[9] Inspired by the live performances of Bob Dylan and The Paul Butterfield Blues Band, the group became fully intertwined in electric rock, and recorded a new electrified version of "I-Feel-Like-I'm-Fixin'-to-Die Rag" in Sierra Sound Laboratories, in February 1967.[10][11] Initially, the song was going to be featured on Country Joe and the Fish's debut album, Electric Music for the Mind and Body, but record producer Sam Charters insisted that the track remain off the record. When the controversial composition "Superbird" was not banned from airplay, "I-Feel-Like-I'm-Fixin'-to-Die Rag" was placed as the opening to their second album, I Feel Like I'm Fixin' to Die.[12][13]

The song was a popular attraction in the band's live performance. The song began with a "Fish Cheer", in which the band spells out the word "F-I-S-H" in the manner of cheerleaders at American football games ("Give me an F", etc.).[7] In the summer of 1968, the first instance of the slightly altered version known as "The Fuck Cheer" appeared in New York City at the Shaefer Summer Music Festival, among a crowd of nearly 10,000. Drummer Gary "Chicken" Hirsh suggested that the opening chorus spell out "fuck", which was positively received by younger listeners, and led to unexpected radio exposure of the album version on both alternative radio stations and AM radio.[14] Although Hirsh has never explained why he made the change, writer James E. Perone has speculated in his book Songs of the Vietnam Conflict that it was a "rebellious counterculture political act demonstrating free speech rights in the mid-1960s".[15] However, executives from The Ed Sullivan Show were present at the concert, and barred Country Joe and the Fish from their scheduled appearance and any future performances on the show.[5]

This version of "I-Feel-Like-I'm-Fixin'-to-Die Rag" was issued as a single in Sweden through Vanguard Records in 1968.[16] It was backed by "Rock And Soul Music", another original by the band which had appeared on their third album Together in August 1968.[16][17][18] Although this release failed to chart, the group saw critical success in Sweden following a tour there during the autumn of 1968.[19] This led Vanguard to re-release the single in April 1969 after which it charted on Tio i Topp.[20] It entered that chart at a position of number seven on April 12, 1969, before peaking at number one on May 17, 1969, staying at the top for four weeks.[21] It exited the chart at a position of number 13 on June 28.[22] Following this, it also charted on sales chart Kvällstoppen on May 20 at a position of number 16 before peaking at number four on June 3.[23] It exited the chart on July 1, having spent seven weeks on the chart.[23] The single was imported to Denmark, where it reached number three.[24] Following the success of the song in Sweden, Vanguard released in as a single across Europe and in Japan throughout 1969 and 1970, though it failed to chart in those territories.[16]

Woodstock performance

editOn August 16, 1969, the second day of the Woodstock Festival, McDonald made an unexpected solo performance of "The Fuck Cheer" at the conclusion of his set list, after Quill. McDonald was augmented with a Yamaha FG 150 guitar that he found and holstered with a rope.[25] According to McDonald, "I went on with my guitar and it was like 'Here is this guy who's going to sing' but no one paid any attention. I played 'Janis' and 'Tennessee Stud' and then I walked off the stage. I asked my tour manager if he thought it would be OK if I went back on and did the cheer and he said yeah. So I went "Give me an F!", and they all yelled "F!"[26] The audience receptively responded by cheering the "F-U-C-K" chant along with McDonald. The performance was featured on the Woodstock film, which included sing-a-long lyrical subtitles of "The Fuck Cheer".[27] Country Joe and the Fish also performed on the third day of the festival, and also concluded their set with the cheer and "Fixin'-to-Die Rag".

Copyright lawsuit

editIn 2001, the heirs of New Orleans jazz trombonist Kid Ory launched a lawsuit against Country Joe McDonald, claiming that the music of "I-Feel-Like-I'm-Fixin'-to-Die Rag" constituted plagiarism of "Muskrat Ramble", a number by Ory,[28][29] recorded by Louis Armstrong and His Hot Five in 1926. In 2005, a court dismissed the suit, holding that the Ory estate had waited too long to make the claim. If the action had been successful, Country Joe McDonald would have been required to pay $150,000 for each live performance of the song in the three years since the lawsuit was filed. McDonald would have also been barred from ever performing the song again without the possibility of further damages.[28]

Charts

edit| Chart (1969) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Denmark (Tipparaden)[24] | 3 |

| Sweden (Kvällstoppen)[23] | 4 |

| Sweden (Tio i Topp)[22] | 1 |

Covers and features

editPete Seeger covered the song in 1970. There were initially plans to release his version as a single, and indeed some copies were sent out to DJs, but according to Seeger, distributors refused to handle it, and it was never officially released. It eventually found its way onto the Internet.[30] It was also included as a bonus track on a reissue of his 1969 album Young vs. Old.[31]

McDonald performed part of the song while playing a folksinging hippie named "Joaquin" in the Tales of the City TV miniseries.[32]

McDonald has said that American prisoner of war Phillip N. Butler told him that the song was regularly broadcast into Hỏa Lò Prison (the "Hanoi Hilton"), in North Vietnam, to the POWs by their captors, and Butler told him that the song actually boosted their morale as they hummed along.[33]

Eugene Chadbourne released two different rewritten versions. The first was in 1986, on his album Corpses of Foreign Wars, and was about the Iran-Iraq War.[34] The second, about the Gulf War, was entitled "Feel Like I'm Fixin' to Die (Iraq)," on his 1991 7" single Oil of Hate. In the liner notes of the latter, he reveals that he also did versions about Grenada and Panama, and adds, "Stay tuned for further developments from the race that can't quit fighting!"[35]

The Passion Killers, comprising several members of the band Chumbawamba, covered the song with modified lyrics on their 1991 single, "Whoopee! We're All Gonna Die!", as a protest against the first Gulf War.[36][37]

Japanese band Omoide Hatoba included a 40-second-long cover on their 1992 album Black Hawaii, with the title reading "I-Feel-Like-I'm-Fix-in-to-Die Rag." Sung by Public Bath Records' David Hopkins, it consists of the intro (on brass instruments), first verse (rap-style drums and vocals), chorus (switching back to brass, with vocals), and the chorus starting to repeat when Seiichi Yamamoto cuts it off by shouting "Next!"

Swedish rock singer Svante Karlsson covered it in 2003 on his album Autograph. This version features a solo performed by legendary guitarist Albert Lee.

Bruno Blum changed the lyrics from the Vietnam-oriented original to an Iran-oriented parody and recorded it as "I-Feel-Like-I'm-Fixin'-to-Die Rag (Revisited)" released on his 2017 Rock n roll de luxe album.

The song has been featured in the films Woodstock (1970), More American Graffiti (1979), Purple Haze (1982), My Science Project (1985), and Hamburger Hill (1987), and the HBO miniseries Generation Kill (2008). It was also featured in the TV show The Wonder Years, in the season 2 episode, titled "Walk Out" (1989).

It was referenced on the 2008 edition of the AP United States History exam.[38]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Unterberger, Richie. "Great Moments in Folk Rock: Lists of Author Favorites". www.richieunterberger.com. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ Buckley, Peter (2003). The Rough Guide to Rock. Rough Guides. p. 234. ISBN 978-1-84353-105-0.

- ^ Selvin, Joel. "Country Joe McDonald Biography". ci.berkeley.ca.us. Retrieved June 24, 2015.

- ^ a b Collectors Items: The First Three EP's (CD booklet). One Way Records. 1994.

- ^ a b Belmont, Bill. "A History". well.com. Retrieved June 26, 2015.

- ^ a b McDonald, Country Joe. "How I Wrote the Rag". countryjoe.com. Retrieved June 26, 2015.

- ^ a b Gilliland, John (1969). "Show 42 - The Acid Test: Psychedelics and a sub-culture emerge in San Francisco" (audio). Pop Chronicles. University of North Texas Libraries.

- ^ I Feel Like I'm Fixin' to Die (CD booklet). Ace Vanguard Masters. 2013.

- ^ "Country Joe McDonald". countryjoe.com. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- ^ Breznikar, Klemen (February 15, 2015). "Country Joe and the Fish interview with Joe McDonald". It's Psychedelic Baby! Magazine. Archived from the original on September 16, 2016. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie (2003). Eight Miles High: Folk-rock's Flight from Haight-Ashbury to Woodstock. Backbeat Books. p. 27. ISBN 978-0879307431.

- ^ Eder, Bruce. "Country Joe and the Fish – Biography". allmusic.com. Retrieved June 29, 2015.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie. "I Feel Like I'm Fixin' to Die – Review". allmusic.com. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ Eder, Bruce. "Gary "Chicken" Hirsh – Biography". allmusic.com. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ Perone, James E. (2001). Songs of the Vietnam Conflict. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 40. ISBN 978-0313315282.

- ^ a b c Helander, Brock (1999). The Rockin' '60s: The People who Made the Music. Schirmer Books. p. 87. ISBN 9780028648736.

- ^ Oberman, Michael (2020). Fast Forward, Play, and Rewind. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 124.

- ^ "AllMusic Review by William Ruhlmann". AllMusic. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ Hallberg, Eric; Henningsson, Ulf (1998). Eric Hallberg, Ulf Henningsson presenterar Tio i topp med de utslagna på försök: 1961 - 74. Premium Publishing. p. 95. ISBN 919727125X.

- ^ Hallberg, Eric; Henningsson, Ulf (1998). Eric Hallberg, Ulf Henningsson presenterar Tio i topp med de utslagna på försök: 1961 - 74. Premium Publishing. p. 95. ISBN 919727125X.

- ^ Hallberg, Eric; Henningsson, Ulf (1998). Eric Hallberg, Ulf Henningsson presenterar Tio i topp med de utslagna på försök: 1961 - 74. Premium Publishing. pp. 468–469. ISBN 919727125X.

- ^ a b Hallberg, Eric; Henningsson, Ulf (1998). Eric Hallberg, Ulf Henningsson presenterar Tio i topp med de utslagna på försök: 1961 - 74. Premium Publishing. p. 469. ISBN 919727125X.

- ^ a b c Hallberg, Eric (1993). Eric Hallberg presenterar Kvällstoppen i P 3: Sveriges radios topplista över veckans 20 mest sålda skivor 10. 7. 1962 - 19. 8. 1975. Drift Musik. p. 230. ISBN 9163021404.

- ^ a b "Tipparaden - Uge 16". Danske Hitlister. April 14, 1969. Archived from the original on March 24, 2016. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ "Woodstock 1969-1999". countryjoe.com. Retrieved July 2, 2015.

- ^ Johnson, Phil (May 11, 1998). "Feel Like I'm Fixin' For a Comeback..." independent.co.uk. Retrieved July 2, 2015.

- ^ "Country Joe McDonald interview". hightimes.com. Archived from the original on July 4, 2015. Retrieved July 2, 2015.

- ^ a b "Country Joe Sued For Stealing Protest Song". Billboard. October 16, 2001.

- ^ "Country Joe McDonald Accused Of Ripping Off Jazz Great". MTV. Archived from the original on November 10, 2013.

- ^ "Country Joe McDonald, the "Suppressed" Seeger recording". countryjoe.com.

- ^ the omni recording corporation Archived February 3, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Armistead Maupin's Tales of the City (TV Mini-Series 1993)". IMDb.

- ^ Appy, Christian G. (2003). Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered from All Sides. New York: Penguin Books. p. 198. ISBN 067003214X.

- ^ "Eugene Chadbourne - Corpses of Foreign Wars". Discogs. Retrieved January 21, 2024.

- ^ Chadbourne, Eugene (1991). "Oil Of Hate". Discogs. Retrieved January 13, 2017.

- ^ "Country Joe McDonald, How I Wrote the Rag". countryjoe.com.

- ^ Chumbawamba Discography

- ^ "Repository" (PDF). apcentral.collegeboard.com.