Elamite, also known as Hatamtite and formerly as Scythic, Median, Amardian, Anshanian and Susian, is an extinct language that was spoken by the ancient Elamites. It was recorded in what is now southwestern Iran from 2600 BC to 330 BC.[1] Elamite is generally thought to have no demonstrable relatives and is usually considered a language isolate. The lack of established relatives makes its interpretation difficult.[2]

| Elamite | |

|---|---|

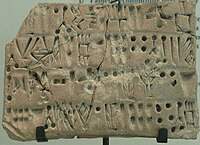

Tablet in Proto-Elamite script | |

| Native to | Elam |

| Region | Western Asia, Iran |

| Era | c. 2800–300 BC (Later unwritten forms might have survived until 1000 AD?) |

Early form | language of Proto-Elamite?

|

| Linear Elamite, Elamite cuneiform | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | elx |

| ISO 639-3 | elx |

elx | |

| Glottolog | elam1244 |

A sizeable number of Elamite lexemes are known from the Achaemenid royal inscriptions – trilingual inscriptions of the Achaemenid Empire, in which Elamite was written using Elamite cuneiform (circa 5th century BC), which is fully deciphered. An important dictionary of the Elamite language, the Elamisches Wörterbuch was published in 1987 by W. Hinz and H. Koch.[3][4] The Linear Elamite script however, one of the scripts used to write the Elamite language circa 2000 BC, has remained elusive until recently.[5][6]

Writing system

editThe following scripts are known or assumed to have encoded Elamite:[7]

- Proto-Elamite script is the oldest known writing system from Iran. It was used during a brief period of time (c. 3100–2900 BC); clay tablets with Proto-Elamite writing have been found at different sites across Iran. It is thought to have developed from early cuneiform (proto-cuneiform) and consists of more than 1,000 signs. It is thought to be largely logographic and is not deciphered.

- Linear Elamite is attested in a few monumental inscriptions. It has been described either as a syllabic or logosyllabic writing system. At least part of the script has been deciphered and it has been argued to have developed from Proto-Elamite, although the exact nature of the relationship between the two is disputed (see the main article). Linear Elamite was used for a very brief period of time during the last quarter of the third millennium BC.

Later, Elamite cuneiform, adapted from Akkadian cuneiform, was used from c. 2500 on.[8] Elamite cuneiform was largely a syllabary of some 130 glyphs at any one time and retained only a few logograms from Akkadian but, over time, the number of logograms increased. The complete corpus of Elamite cuneiform consists of about 20,000 tablets and fragments. The majority belong to the Achaemenid era, and contain primarily economic records.

Linguistic typology

editElamite is an agglutinative language,[9] and its grammar was characterized by an extensive and pervasive nominal class system. Animate nouns have separate markers for first, second and third person. It can be said to display a kind of Suffixaufnahme in that the nominal class markers of the head are also attached to any modifiers, including adjectives, noun adjuncts, possessor nouns and even entire clauses.

History

editThe history of Elamite is periodised as follows:

- Old Elamite (c. 2600–1500 BC)

- Middle Elamite (c. 1500–1000 BC)

- Neo-Elamite (1000–550 BC)

- Achaemenid Elamite (550–330 BC)

- Late Elamite?

- Khuzi? (Unknown – 1000 AD)

Middle Elamite is considered the “classical” period of Elamite, but the best attested variety is Achaemenid Elamite,[10] which was widely used by the Achaemenid Persian state for official inscriptions as well as administrative records and displays significant Old Persian influence.

Persepolis Administrative Archives were found at Persepolis in 1930s, and they are mostly in Elamite; the remains of more than 10,000 of these cuneiform documents have been uncovered. In comparison, Aramaic is represented by only 1,000 or so original records.[11] These documents represent administrative activity and flow of data in Persepolis over more than fifty consecutive years (509 to 457 BC).

Documents from the Old Elamite and early Neo-Elamite stages are rather scarce.

Neo-Elamite can be regarded as a transition between Middle and Achaemenid Elamite, with respect to language structure.

The Elamite language may have remained in widespread use after the Achaemenid period. Several rulers of Elymais bore the Elamite name Kamnaskires in the 2nd and 1st centuries BC. The Acts of the Apostles (c. 80–90 AD) mentions the language as if it was still current. There are no later direct references, but Elamite may be the local language in which, according to the Talmud, the Book of Esther was recited annually to the Jews of Susa in the Sasanian period (224–642 AD). Between the 8th and 13th centuries AD, various Arabic authors refer to a language called Khuzi or Xūz spoken in Khuzistan, which was unlike any other Iranian language known to those writers. It is possible that it was "a late variant of Elamite".[12]

The last original report on the Xūz language was written circa 988 AD by Al-Muqaddasi, characterizing the Khuzi as bilingual in Arabic and Persian but also speaking an "incomprehensible" language at the town of Ramhormoz. The town had recently become prosperous again after the foundation of a market, and as it received an influx of foreigners and being a "Khuzi" was stigmatized at the time, the language probably died in the 11th century.[13] Later authors only mention the language when citing previous work.

Phonology

editBecause of the limitations of the language's scripts, its phonology is not well understood.

Its consonants included at least stops /p/, /t/ and /k/, sibilants /s/, /ʃ/ and /z/ (with an uncertain pronunciation), nasals /m/ and /n/, liquids /l/ and /r/ and fricative /h/, which was lost in late Neo-Elamite. Some peculiarities of the spelling have been interpreted as suggesting that there was a contrast between two series of stops (/p/, /t/, /k/ as opposed to /b/, /d/, /ɡ/), but in general, such a distinction was not consistently indicated by written Elamite.[14]

Elamite had at least the vowels /a/, /i/, and /u/ and may also have had /e/, which was not generally expressed unambiguously.[15]

Roots were generally CV, (C)VC, (C)VCV or, more rarely, CVCCV[16] (the first C was usually a nasal).

Morphology

editElamite is agglutinative but with fewer morphemes per word than, for example, Sumerian or Hurrian and Urartian. It is mostly suffixing.

Nouns

editThe Elamite nominal system is thoroughly pervaded by a noun class distinction, which combines a gender distinction between animate and inanimate with a personal class distinction, corresponding to the three persons of verbal inflection (first, second, third, plural).

The suffixes that express that system are as follows:[16]

Animate:

- 1st person singular: -k

- 2nd person singular: -t

- 3rd person singular: -r or -Ø

- 3rd person plural: -p

Inanimate:

- -∅, -me, -n, -t[17]

The animate third-person suffix -r can serve as a nominalizing suffix and indicate nomen agentis or just members of a class. The inanimate third-person singular suffix -me forms abstracts.

Some examples of the use of the noun class suffixes above are the following:

- sunki-k “a king (first person)” i.e. “I, a king”

- sunki-r “a king (third person)”

- nap-Ø or nap-ir “a god (third person)”

- sunki-p “kings”

- nap-ip “gods”

- sunki-me “kingdom, kingship”

- hal-Ø “town, land”

- siya-n “temple”

- hala-t “mud brick”.

Modifiers follow their (nominal) heads. In noun phrases and pronoun phrases, the suffixes referring to the head are appended to the modifier, regardless of whether the modifier is another noun (such as a possessor) or an adjective. Sometimes the suffix is preserved on the head as well:

- u šak X-k(i) = “I, the son of X”

- X šak Y-r(i) = “X, the son of Y”

- u sunki-k Hatamti-k = “I, the king of Elam”

- sunki Hatamti-p (or, sometimes, sunki-p Hatamti-p) = “the kings of Elam”

- temti riša-r = “great lord” (lit. “lord great”)

- riša-r nap-ip-ir = “greatest of the gods” (lit. "great of the gods")

- nap-ir u-ri = “my god” (lit. “god of me”)

- hiya-n nap-ir u-ri-me = “the throne hall of my god”

- takki-me puhu nika-me-me = “the life of our children”

- sunki-p uri-p u-p(e) = ”kings, my predecessors” (lit. “kings, predecessors of me”)

This system, in which the noun class suffixes function as derivational morphemes as well as agreement markers and indirectly as subordinating morphemes, is best seen in Middle Elamite. It was, to a great extent, broken down in Achaemenid Elamite, where possession and, sometimes, attributive relationships are uniformly expressed with the “genitive case” suffix -na appended to the modifier: e.g. šak X-na “son of X”. The suffix -na, which probably originated from the inanimate agreement suffix -n followed by the nominalizing particle -a (see below), appeared already in Neo-Elamite.[18]

The personal pronouns distinguish nominative and accusative case forms. They are as follows:[19]

| Singular | Plural | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | Accusative | Nominative | Accusative | |

| 1st person | u | un | nika/nuku | nukun |

| 2nd person | ni/nu | nun | num/numi | numun |

| 3rd person | i/hi | ir/in | ap/appi | appin |

| Inanimate | i/in | |||

In general, no special possessive pronouns are needed in view of the construction with the noun class suffixes. Nevertheless, a set of separate third-person animate possessives -e (sing.) / appi-e (plur.) is occasionally used already in Middle Elamite: puhu-e “her children”, hiš-api-e “their name”.[19] The relative pronouns are akka “who” and appa “what, which”.[19]

Verbs

editThe verb base can be simple (ta- “put”) or “reduplicated” (beti > bepti “rebel”). The pure verb base can function as a verbal noun, or “infinitive”.[22]

The verb distinguishes three forms functioning as finite verbs, known as “conjugations”.[23] Conjugation I is the only one with special endings characteristic of finite verbs as such, as shown below. Its use is mostly associated with active voice, transitivity (or verbs of motion), neutral aspect and past tense meaning. Conjugations II and III can be regarded as periphrastic constructions with participles; they are formed by the addition of the nominal personal class suffixes to a passive perfective participle in -k and to an active imperfective participle in -n, respectively.[22] Accordingly, conjugation II expresses a perfective aspect, hence usually past tense, and an intransitive or passive voice, whereas conjugation III expresses an imperfective non-past action.

The Middle Elamite conjugation I is formed with the following suffixes:[23]

| singular | plural | |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person | -h | -hu |

| 2nd person | -t | -h-t |

| 3rd person | -š | -h-š |

- Examples: kulla-h ”I prayed”, hap-t ”you heard”, hutta-š “he did”, kulla-hu “we prayed”, hutta-h-t “you (plur.) did”, hutta-h-š “they did”.

In Achaemenid Elamite, the loss of the /h/ reduces the transparency of the Conjugation I endings and leads to the merger of the singular and plural except in the first person; in addition, the first-person plural changes from -hu to -ut.

The participles can be exemplified as follows: perfective participle hutta-k “done”, kulla-k “something prayed”, i.e. “a prayer”; imperfective participle hutta-n “doing” or “who will do”, also serving as a non-past infinitive. The corresponding conjugations (conjugation II and III) are:

| perfective (= conj. II) |

imperfective (= conj. III) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | singular | hutta-k-k | hutta-n-k |

| 2nd person | singular | hutta-k-t | hutta-n-t |

| 3rd person | singular | hutta-k-r | hutta-n-r |

| plural | hutta-k-p | hutta-n-p | |

In Achaemenid Elamite, the Conjugation 2 endings are somewhat changed:[24]

| 1st person | singular | hutta-k-ut |

|---|---|---|

| 2nd person | singular | hutta-k-t |

| 3rd person | singular | hutta-k (hardly ever attested in predicative use) |

| plural | hutta-p |

There is also a periphrastic construction with an auxiliary verb ma- following either Conjugation II and III stems (i.e. the perfective and imperfective participles), or nomina agentis in -r, or a verb base directly. In Achaemenid Elamite, only the third option exists. There is no consensus on the exact meaning of the periphrastic forms with ma-, but durative, intensive or volitional interpretations have been suggested.[25]

The optative is expressed by the addition of the suffix -ni to Conjugations I and II.[25]

The imperative is identical to the second person of Conjugation I in Middle Elamite. In Achaemenid Elamite, it is the third person that coincides with the imperative.[22]

The prohibitative is formed by the particle anu/ani preceding Conjugation III.[22]

Verbal forms can be converted into the heads of subordinate clauses through the addition of the nominalising suffix -a, much as in Sumerian: siyan in-me kuši-hš(i)-me-a “the temple which they did not build”. -ti/-ta can be suffixed to verbs, chiefly of conjugation I, expressing possibly a meaning of anteriority (perfect and pluperfect tense).[26]

The negative particle is in-; it takes nominal class suffixes that agree with the subject of attention (which may or may not coincide with the grammatical subject): first-person singular in-ki, third-person singular animate in-ri, third-person singular inanimate in-ni/in-me. In Achaemenid Elamite, the inanimate form in-ni has been generalized to all persons, and concord has been lost.

Syntax

editNominal heads are normally followed by their modifiers, but there are occasional inversions. Word order is subject–object–verb (SOV), with indirect objects preceding direct objects, but it becomes more flexible in Achaemenid Elamite.[27] There are often resumptive pronouns before the verb – often long sequences, especially in Middle Elamite (ap u in duni-h "to-them I it gave").[28]

The language uses postpositions such as -ma "in" and -na "of", but spatial and temporal relationships are generally expressed in Middle Elamite by means of "directional words" originating as nouns or verbs. They can precede or follow the governed nouns and tend to exhibit noun class agreement with whatever noun is described by the prepositional phrase: i-r pat-r u-r ta-t-ni "may you place him under me", lit. "him inferior of-me place-you-may". In Achaemenid Elamite, postpositions become more common and partly displace that type of construction.[27]

A common conjunction is ak "and, or". Achaemenid Elamite also uses a number of subordinating conjunctions such as anka "if, when" and sap "as, when". Subordinate clauses usually precede the verb of the main clause. In Middle Elamite, the most common way to construct a relative clause is to attach a nominal class suffix to the clause-final verb, optionally followed by the relativizing suffix -a: thus, lika-me i-r hani-š-r(i) "whose reign he loves", or optionally lika-me i-r hani-š-r-a. The alternative construction by means of the relative pronouns akka "who" and appa "which" is uncommon in Middle Elamite, but gradually becomes dominant at the expense of the nominal class suffix construction in Achaemenid Elamite.[29]

Language samples

editMiddle Elamite (Šutruk-Nahhunte I, 1200–1160 BC; EKI 18, IRS 33):

Transliteration:

(1) ú DIŠšu-ut-ru-uk-dnah-hu-un-te ša-ak DIŠhal-lu-du-uš-din-šu-ši-

(2) -na-ak-gi-ik su-un-ki-ik an-za-an šu-šu-un-ka4 e-ri-en-

(3) -tu4-um ti-pu-uh a-ak hi-ya-an din-šu-ši-na-ak na-pír

(4) ú-ri-me a-ha-an ha-li-ih-ma hu-ut-tak ha-li-ku-me

(5) din-šu-ši-na-ak na-pír ú-ri in li-na te-la-ak-ni

Transcription:

U Šutruk-Nahhunte, šak Halluduš-Inšušinak-(i)k, sunki-k Anzan Šušun-k(a). Erientum tipu-h ak hiya-n Inšušinak nap-(i)r u-r(i)-me ahan hali-h-ma. hutta-k hali-k u-me Inšušinak nap-(i)r u-r(i) in lina tela-k-ni.

Translation:

I, Šutruk-Nahhunte, son of Halluduš-Inšušinak, king of Anshan and Susa. I moulded bricks and made the throne hall of my god Inšušinak with them. May my work come as an offering to my god Inšušinak.

Achaemenid Elamite (Xerxes I, 486–465 BC; XPa):

Transliteration:

(01) [sect 01] dna-ap ir-šá-ir-ra du-ra-mas-da ak-ka4 AŠmu-ru-un

(02) hi pè-iš-tá ak-ka4 dki-ik hu-ip-pè pè-iš-tá ak-ka4 DIŠ

(03) LÚ.MEŠ-ir-ra ir pè-iš-tá ak-ka4 ši-ia-ti-iš pè-iš-tá DIŠ

(04) LÚ.MEŠ-ra-na ak-ka4 DIŠik-še-ir-iš-šá DIŠEŠŠANA ir hu-ut-taš-

(05) tá ki-ir ir-še-ki-ip-in-na DIŠEŠŠANA ki-ir ir-še-ki-ip-

(06) in-na pír-ra-ma-ut-tá-ra-na-um

Transcription:

Nap irša-r(a) Auramasda, akka muru-n hi pe-š-ta, akka kik hupe pe-š-ta, akka ruh-(i)r(a) ir pe-š-ta, akka šiatiš pe-š-ta ruh-r(a)-na, akka Ikšerša sunki ir hutta-š-ta kir iršeki-p-na sunki, kir iršeki-p-na piramataram.

Translation:

A great god is Ahura Mazda, who created this earth, who created that sky, who created man, who created happiness of man, who made Xerxes king, one king of many, one lord of many.

Relations to other language families

editElamite is regarded by the vast majority of linguists as a language isolate,[30][31] as it has no demonstrable relationship to the neighbouring Semitic languages, Indo-European languages, or to Sumerian, despite having adopted the Sumerian-Akkadian cuneiform script.

An Elamo-Dravidian family connecting Elamite with the Brahui language of Pakistan and Dravidian languages of India was suggested in 1967 by Igor M. Diakonoff[32] and later, in 1974, defended by David McAlpin and others.[33][34] In 2012, Southworth proposed that Elamite forms the "Zagrosian family" along with Brahui and, further down the cladogram, the remaining Dravidian languages; this family would have originated in Southwest Asia (southern Iran) and was widely distributed in South Asia and parts of eastern West Asia before the Indo-Aryan migration.[35] Recent discoveries regarding early population migration based on ancient DNA analysis have revived interest in the possible connection between proto-Elamite and proto-Dravidian.[36][37][38][39] A critical reassessment of the Elamo-Dravidian hypothesis has been published by Filippo Pedron in 2023.[40]

Václav Blažek proposed a relation with the Semitic languages.[41]

In 2002 George Starostin published a lexicostatistic analysis finding Elamite to be approximately equidistant from Nostratic and Semitic.[42]

None of these ideas have been accepted by mainstream historical linguists.[30]

History of the study

editThe study of Elamite language goes back to the first publications of Achaemenid royal inscriptions in Europe in the first half of the 19th century CE. A great step forward was the publication of the Elamite version of the Bisotun inscription in the name of Darius I, entrusted by Henry Rawlinson to Edwin Norris and appeared in 1855. At that time, Elamite was believed to be Scythic, whose Indoeuropean affiliation was not still established. The first grammar was published by Jules Oppert in 1879. The first to use the glottonym Elamite is considered to be Archibald Henry Sayce in 1874, even if already in 1850 Isidore Löwenstern advanced this identification. The publication of pre-Achaemenid inscriptions from Susa is due along the first three decades of the 20th century by father Vincent Scheil. Then in 1933 the Persepolis Fortification Tablets were discovered, being the first administrative corpus in this language, even if published by Richard T. Hallock much later (1969). Another administrative corpus was discovered in the 1970s at Tall-i Malyan, the ancient city of Anshan, and published in 1984 by Matthew W. Stolper. In the meantime (1967), the Middle Elamite inscriptions from Chogha Zanbil were published by father Marie-Joseph Steve. In the fourth quarter of the 20th century the French school was led by François Vallat, with relevant studies by Françoise Grillot(-Susini) and Florence Malbran-Labat, while the American school of scholars, inaugurated by George G. Cameron and Herbert H. Paper, focused on the administrative corpora with Stolper. Elamite studies have been revived in the 2000s by Wouter F.M. Henkelman with several contributions and a monograph focused on the Persepolis Fortification tablets. Elamite language is currently taught in three universities in Europe, by Henkelman at the École pratique des hautes études, Gian Pietro Basello at the University of Naples "L'Orientale" and Jan Tavernier at the UCLouvain.[43]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Stolper 2004, pp. 60–64

- ^ Gragg 2009, p. 316

- ^ Hinz & Koch 1987a

- ^ Hinz & Koch 1987b

- ^ Desset, François (2018). "Linear Elamite writing". The Elamite World: 397. doi:10.4324/9781315658032-21. ISBN 978-1-315-65803-2. in Álvarez-Mon, Basello & Wicks 2018, pp. 405–406

- ^ Desset, François (2022). "The Decipherment of Linear Elamite". Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und vorderasiatische Archäologie: 11–60. doi:10.1515/za-2022-0003. ISSN 1613-1150.

- ^ Stolper 2004, p. 65

- ^ Stolper 2004, pp. 65–66

- ^ Stolper 2004, p. 60

- ^ Gragg 2009, p. 316

- ^ Persepolis Fortification Archive. Oriental Institute – The University of Chicago

- ^ Tavernier, Jan. The Elamite Language. in Álvarez-Mon, Basello & Wicks 2018, pp. 421–422

- ^ van Bladel 2021

- ^ Stolper 2004, p. 70

- ^ Stolper 2004, p. 72

- ^ a b Stolper 2004, p. 73

- ^ Apart from the productive use of -me to form abstract nouns, the meaning (if any) of the difference between the various inanimate suffixes is unclear.

- ^ Stolper 2004, p. 74

- ^ a b c Stolper 2004, p. 75

- ^ "The Darius Seal". British Museum. Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- ^ Darius' seal: photo – Livius.

- ^ a b c d Stolper 2004, p. 81

- ^ a b Stolper 2004, p. 78

- ^ Stolper 2004, p. 79

- ^ a b Stolper 2004, p. 80

- ^ Stolper 2004, p. 82

- ^ a b Stolper 2004, p. 84

- ^ Stolper 2004, p. 87

- ^ Stolper 2004, p. 88

- ^ a b Blench & Spriggs 1997, p. 125

- ^

- Woodard 2008, pp. 3

- Gnanadesikan 2009

- Tavernier 2020, p. 164

- ^ Дьяконов 1967

- ^

- ^

- Khačikjan 1998, p. 3

- van Bladel 2021, p. 448

- ^ Southworth 2011

- ^ Joseph 2017

- ^ McAlpin 1981, p. 1

- ^ Zvelebil 1985: I admit that this [reconstruction] is somewhat farfetched. but so is a number of McAlpin's reconstructions. [...] There is no obvious systematic relationship between the morphologies of Elamite and Dravidian, apparent at first sight. Only after a hypothetical reinterpretation, three morphological patterns emerge as cognate systems: the basic cases, the personal pronouns, and the appellative endings. [...] I am also convinced that much additional work is to be done and many changes will be made to remove the genetic cognation in question from the realm of hypothesis and establish it as a fact acceptable to all.

- ^ Krishnamurti 2003, pp. 44–45: Many of the rules formulated by McAlpin lack intrinsic phonetic/phonological motivation and appear ad hoc, invented to fit the proposed correspondences: e.g. Proto-Elamo-Dravidian *i, *e > Ø Elamite, when followed by t, n, which are again followed by a; but these remain undisturbed in Dravidian (1974: 93). How does a language develop that kind of sound change? This rule was dropped a few years later, because the etymologies were abandoned (see 1979: 184). [...] We need more cognates of an atypical kind to rule out the possibility of chance.

- ^ Pedron 2023

- ^ Blench 2006, p. 96

- ^ Starostin 2002

- ^ Basello, Gian Pietro (2004). "Elam between Assyriology and Iranian Studies". In Panaino, Antonio (ed.). Melammu Symposia IV (PDF). Università di Bologna & IsIAO. pp. 1–40. ISBN 978-8884831071.

Bibliography

editIntroductions and overviews

edit- Álvarez-Mon, Javier; Basello, Gian Pietro; Wicks, Jasmina, eds. (2018). The Elamite World. London/New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781315658032.

- van Bladel, Kevin (2021). "The Language Of The Xūz And The Fate Of Elamite". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 31 (3): 447–462. doi:10.1017/S1356186321000092.

- Blench, Roger; Spriggs, Matthew, eds. (1997). Theoretical and Methodological Orientations. Archaeology and Language. Vol. 1. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415117609.

- Gragg, Gene B. (2009). "Elamite". In Brown, Edward Keith; Ogilvie, Sarah (eds.). Concise encyclopedia of languages of the world. Amsterdam/Oxford: Elsevier. pp. 316–317. ISBN 978-0-08-087774-7.

- Gnanadesikan, Amalia Elisabeth (2009). The writing revolution: cuneiform to the internet. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-405-15406-2.

- Potts, Daniel T. (1999). The archaeology of Elam: formation and transformation of an ancient Iranian state. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511489617..

- Basello, Gian Pietro (2011). "Elamite as Administrative Language: From Susa to Persepolis". In Álvarez-Mon, Javier; Garrison, Mark B. (eds.). Elam and Persia. University Park: Penn State University Press. pp. 61–88. doi:10.1515/9781575066127-008. ISBN 9781575066127. JSTOR 10.5325/j.ctv18r6qxh.

Dictionaries

edit- Hinz, Walther; Koch, Heidemarie (1987a). Elamisches Wörterbuch (in German). Vol. 1. Berlin: Reimer. ISBN 3-496-00923-3.

- Hinz, Walther; Koch, Heidemarie (1987b). Elamisches Wörterbuch (in German). Vol. 2. Berlin: Reimer. ISBN 3-496-00923-3.

Grammars

edit- Дьяконов, Игорь Михайлович (1967). Языки древней Передней Азии [The Languages of Ancient Asia Minor] (in Russian). Moskow: Наука.

- Khačikjan, Margaret (1998). The Elamite Language. Documenta Asiana. Vol. IV. Rome: Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche Istituto per gli Studi Micenei ed Egeo-Anatolici. ISBN 88-87345-01-5.

- Paper, Herbert H. (1955). The phonology and morphology of Royal Achaemenid Elamite. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. LCCN 55-10983.

- Stolper, Matthew W. (2004). "Elamite". In Woodard, Roger D. (ed.). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World's Ancient Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 60–95. ISBN 978-0-521-56256-0.

- Republished in Woodard, Roger D., ed. (2008). The Ancient Languages of Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Aksum. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 60–95. ISBN 9780521684972.

- Tavernier, Jan (2020). "Elamite". In Hasselbach-Andee, Rebecca (ed.). A companion to ancient Near Eastern languages. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell. pp. 163–184. ISBN 9781119193296.

- Basello, Gian Pietro (2023). "An Introduction to Elamite Language". In Basello, Gian Pietro (ed.). Studies on Elamite & Mesopotamian Cuneiform Culture (PDF). Durham, NC: Lulu. pp. 7–47. ISBN 978-1-4476-3979-4.

Genetic affiliation

edit- Blench, Roger (2006). Archaeology, Language, and the African Past. African Archaeology Series. Lanham: Rowman AltaMira. ISBN 978-0-7591-0466-2. ISSN 2691-8773. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- Joseph, Tony (2017). Early Indians : the story of our ancestors and where we came from. New Delh: Juggernaut. ISBN 978-93-86228-98-7. OCLC 1112882321.

- Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju (2003). The Dravidian Languages. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139435338.

- McAlpin, David W. (1974). "Toward Proto-Elamo-Dravidian". Language. 50 (1): 89–101. doi:10.2307/412012. JSTOR 412012.

- McAlpin, David W. (1975). "Elamite and Dravidian, Further Evidence of Relationships". Current Anthropology. 16 (1). doi:10.1086/201521.

- McAlpin, David W. (1979). "Linguistic prehistory: the Dravidian situation". In Deshpande, Madhav M.; Hook, Peter Edwin (eds.). Aryan and Non-Aryan in India. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. pp. 175–190. doi:10.3998/mpub.19419. ISBN 978-0-472-90168-5. JSTOR 10.3998/mpub.19419.10.

- McAlpin, David W. (1981). "Proto-Elamo-Dravidian: The Evidence and Its Implications". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 71 (3): 1–155. doi:10.2307/1006352. JSTOR 1006352.

- Pedron, Filippo (2023). Elamite and Dravidian: A Reassessment. Thiruvananthapuram, India: International School of Dravidian Linguistics. ISBN 9788196007546.

- Southworth, Franklin (2011). "Rice in Dravidian and its linguistic implications". Rice. 4: 142–148. Bibcode:2011Rice....4..142S. doi:10.1007/s12284-011-9076-9.

- Starostin, George (2002). "On the genetic affiliation of the Elamite language". Mother Tongue. VII: 147–217. ISSN 1087-0326.

- Zvelebil, Kamil V. (1985). "Review of Proto-Elamo-Dravidian: The Evidence and Its Implications". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 105 (2): 364–372. doi:10.2307/601741. ISSN 0003-0279. JSTOR 601741.

External links

edit- Hinz, Walther; Koch, Heidemarie (1987). Elamisches Wörterbuch. Berlin: Reimer. ISBN 978-3-496-00923-8. Part 1: A–H, Part 2: I–Z.

- Ancient Scripts: Elamite

- Elamisch by Ernst Kausen (in German). An overview of Elamite.

- Elamite grammar, glossary, and a very comprehensive text corpus, by Enrique Quintana (in some respects, the author's views deviate from those generally accepted in the field) (in Spanish)

- Эламский язык, a detailed description by Igor Diakonov (in Russian)

- Persepolis Fortification Archive Archived 2011-08-23 at the Wayback Machine (requires Java)

- Achaemenid Royal Inscriptions project (the project is discontinued, but the texts, the translations and the glossaries remain accessible on the Internet Archive through the options "Corpus Catalogue" and "Browse Lexicon")

- On the genetic affiliation of the Elamite language by George Starostin (the Nostratic theory; also with glossary)

- Elamite and Dravidian: Further Evidence of Relationship by David McAlpin