Palenquero (sometimes spelled Palenkero) or Palenque (Palenquero: Lengua) is a Spanish-based creole language spoken in Colombia. It is believed to be a mixture of Kikongo (a language spoken in central Africa in the current countries of Congo, DRC, Gabon, and Angola, former member states of Kongo) and Spanish. However, there is not sufficient evidence to indicate that Palenquero is strictly the result of a two-language contact. It could also have absorbed elements of local indigenous languages.[4]

| Palenquero | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Colombia |

| Region | San Basilio de Palenque |

| Ethnicity | 6,637 (2018)[1] |

Native speakers | 2,788 (2005)[2] |

Spanish Creole

| |

| Latin (Spanish alphabet) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | The Colombian constitution recognizes minority languages as "official in their territories."[3] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | pln |

| Glottolog | pale1260 |

| ELP | Palenquero |

| Linguasphere | 51-AAC-bc |

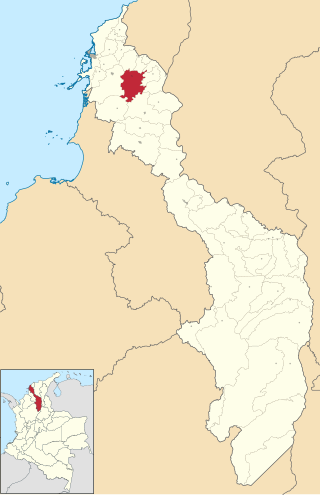

Map highlighting Mahates municipality, where Palenque is located | |

Palenquero is considered to be the only surviving Spanish-based creole language in Latin America.[5] In 2018 more than 6,600 people spoke this language.[1]

It is primarily spoken in the village of San Basilio de Palenque, which is southeast of Cartagena, and in some neighbourhoods of Barranquilla.[6]

History

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2018) |

The formation of Palenquero is recorded from the 17th century with the dilution of the Spanish language and the increase of maroon activity.[7] Existing records dating from the era of Cartagena’s slave trade allude to the pidgin from which Palenquero evolved. As illustrated in the ethnographic text of De Instauranda Aethiopum Salute (1627), the priest Alonso de Sandoval refers to the ‘corruption of our Spanish language’ commonly spoken amongst African slaves.[7] Palenquero's origins are unclear; it was not referred to in print until 1772.[7]

Palenque de San Basilio

editPalenque de San Basilio or San Basilio de Palenque is the village from which Palenquero originated from and in which it is most commonly spoken in the 21st century.

The village was formed in the early 17th century to the south of Cartagena by fugitive slaves who escaped from surrounding districts, under the leadership of Benkos Biohó.[6] The dissolution of the Spanish language intensified as maroons settled in armed fortified territories. The Palenqueros maintained their physical distance from ethnic Europeans as a form of anti-colonial resistance but they likely intermarried with indigenous women. They developed a creole based mostly on their own African languages and Spanish.

In the early 20th century, residents of this area were noted as having been bilingual in both Palenquero and Spanish. A 1913 document noted that residents of Palenque de San Basilio had a 'guttural dialect that some believe to be the very African language, if not in all its purity at least with some variations'.[8]

Decline

editFor almost two decades in the 21st century, Palenquero has been classified as an endangered language. Although it is spoken in parallel with Spanish, the latter has dominated the regular linguistic activity of Palenque de San Basilio. Some 53% of residents are unable to speak Palenquero.

The decline of Palenquero can be traced to the establishment of sugar and banana plantations. Many natives left the village in order to find work either in the Panama Canal or the Department of Magdalena.[6] There they came into contact with other languages. In the 20th century, with the introduction of a standard Spanish educational system, Spanish became the supra regional prescriptive speech, and Palenquero was often criticized and mocked.[9]

Racial discrimination against people of ethnic African descent added to the decline of Palenquero. Some parents did not feel comfortable continuing to teach their children the language.[10]

Revitalization

editWith its legacy of cultural resistance, Palenquero has survived since the early 17th century despite the many challenges. In recent years, scholars and activists have encouraged teaching and use of Palenquero, and native speakers are encouraged.[11] Three major events have contributed to the revived interest in the Palenquero creole:

Antonio Cervantes

editAntonio Cervantes, also known as Kid Pambelé, is an internationally recognized boxing champion born in Palenque de San Basilio. After he won the 1972 world Jr. Welterweight championship, local residents took pride in both the village and Palenquero as a language. As result, Palenque de San Basilio attracted interest by many journalists and politicians.[9] It has continued to attract cultural and foreign attention.

UNESCO Heritage of Humanity

editIn 2005, Palenque was declared by the United Nations to be a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity. The recognition has led to appreciation for Palenquero culture. Films, documentaries and music festivals have brought more attention to the community.[9] These type of cultural programs have successfully appealed to Colombian youth, who otherwise were not interested in Palenquero.

Academic Interest

editBeginning in 1992, the educational system in Palenque de San Basilio started reintroducing Palenquero in the curriculum. Children resumed learning Palenquero, as it was introduced in preschool, and they continued to learn it in advancing grades. Parents and grandparents were encouraged to use the language at home, and classes were opened for adults. A fully equipped cultural centre was constructed to promote the language and culture.[9]

Additionally, academic research, conferences and activism have increased the desirability of Palenquero. There is new energy to continue to pass it down generations.

Language distinctions

editThis section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (August 2024) |

Grammar

editSimilar to several other creole languages, Palenquero grammar lacks inflectional morphology. Nouns, adjectives, verbs and determiners are almost always invariant.[12]

Gender

editGrammatical gender is non-existent, and adjectives derived from Spanish default to the masculine form: lengua africano ‘African language’.[12]

Plurality

editPlurality is marked with the particle ma. (for example: ma posá is "houses"). This particle is believed to derive from Kikongo, a Bantu language, and is the sole Kikongo-derived inflection present in Palenquero.[13] The younger speakers of Palenquero utilize ma for plurality more so than the speakers that came before them.

This particle is usually dropped with cardinal numbers greater than two: ma ndo baka "two cows" but tresi año "13 years".[12]

| Number | Person | Nominative | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | 1st | í | uncertain |

| yo | yo | ||

| 2nd | bo | vos | |

| 3rd | ele | ele | |

| Plural | 1st | suto | nosotros |

| 2nd | utere | ustedes | |

| enu (formerly archaic) | African origin | ||

| 3rd | ané | Bantu origin |

Verbs

editCopula

editPalenquero has four copulas: e, ta, jue, and senda. E roughly corresponds to ser in Spanish and is used for permanent states, and ta is similar to the Spanish estar in that it used for temporary states and locatives. Jue is used as a copula for nouns and senda is only found with predicative nouns and adjectives referring to permanent states.[14]

Examples:[15]

- Bo é mamá mí nu (You are not my mother)

- Mujé mí jue negra i yo jue negro (My wife is black and I am black)

- I tan sendá dotó (I will be a doctor)

- Ese mujé ta ngolo (That woman is fat)

Vocabulary

editSome 300 words of African origin have been identified in Palenquero,[16] with many believed to originate in the Kikongo language. A comprehensive list and proposed etymologies are provided in Moñino and Schwegler's "Palenque, Cartagena y Afro-Caribe: historia y lengua" (2002). Many of the words that come from African origin, include plant, animal, insect and landscape names.[6] Another handful of words are believed to originate from Portuguese (for example: mai 'mother'; ten 'has'; ele 'he/she'; bae 'go').

| Palenque | Spanish | English |

|---|---|---|

| burú | dinero | money |

| ngombe | ganado | cattle |

| ngubá | cacahuete | peanut |

| posá | casa. Compare posada | house |

| tambore | tambor | drum |

| mai | madre. Compare mãe. | mother |

| bumbilo | basura | garbage |

| chepa | ropa | clothing |

| chitiá | hablar | to speak |

| ngaina | gallina | chicken |

| tabaco | tabaco | tobacco |

| hemano | hermano | brother |

| onde | donde | where |

| pueta | puerta | door |

| ngolo | gordo | fat |

| flo | flor | flower |

| moná | niño | child |

| ceddo | cerdo | pig |

| cateyano | castellano | Spanish |

| foratero | forastero | outsider |

| kusa | cosa | thing, stuff |

| cuagro | barrio | neighborhood |

Sample

edit| Palenquero | Spanish |

|---|---|

| Tatá suto lo que ta riba cielo, santificaro sendá nombre si, miní a reino sí, asé ño voluntá sí, aí tiela cumo a cielo. Nda suto agué pan ri to ma ría, peddona ma fata suto, asina cumo suto a se peddoná, lo que se fatá suto. Nu rejá sujo caí andí tentación nu, librá suto ri má. Amén. |

Padre nuestro que estás en el cielo, santificado sea tu nombre. Venga a nosotros tu Reino. Hágase tu voluntad, así en la tierra como en el cielo. Danos hoy nuestro pan de cada día. perdona nuestras ofensas, como también nosotros perdonamos a los que nos ofenden. no nos dejes caer en la tentación, y líbranos del mal. Amén. |

See also

edit- Bozal Spanish – Extinct Spanish creole

References

edit- ^ a b DANE (6 November 2019). Población Negra, Afrocolombiana, Raizal y Palenquera: Resultados del Censo Nacional de Población y Vivienda 2018 (PDF) (in Spanish). DANE. Retrieved 2020-05-11 – via dane.gov.co.

- ^ Ministerio de Cultura (2010). Palenqueros, descendientes de la insurgencia anticolonial (PDF) (in Spanish). p. 2 – via mincultura.gov.co.

- ^ Title 1, Article 10. http://confinder.richmond.edu/admin/docs/colombia_const2.pdf Archived 2011-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Parkvall, Mikael; Jacobs, Bart (2020). "Palenquero Origins: A Tale of More than Two Languages". Diachronica. 37 (4): 540–576. doi:10.1075/dia.19019.par. S2CID 225778990.

- ^ Romero, Simon (2007-10-18). "San Basilio de Palenque Journal - A Language, Not Quite Spanish, With African Echoes - NYTimes.com". www.nytimes.com. Retrieved 2010-02-13.

- ^ a b c d Bickerton, Derek; Escalante, Aquilas (January 1970). "Palenquero: A Spanish-based creole of northern Colombia". Lingua. 24: 254–267. doi:10.1016/0024-3841(70)90080-x. ISSN 0024-3841.

- ^ a b c Dieck, Marianne (2011). "La época de formación de la lengua de Palenque: Datos históricos y lingüísticos" [The Formation Period of the Palenquero Language]. Forma y Función (in Spanish). 24 (1): 11–24. OCLC 859491443.

- ^ Lipski, John (2018). "Palenquero vs. Spanish negation: Separate but equal?". Lingua. 202: 44–57. doi:10.1016/j.lingua.2017.12.007. ISSN 0024-3841.

- ^ a b c d Lipski, John M. (2012). "Free at Last: From Bound Morpheme to Discourse Marker in Lengua ri Palenge (Palenquero Creole Spanish)". Anthropological Linguistics. 54 (2): 101–132. doi:10.1353/anl.2012.0007. ISSN 1944-6527. S2CID 143540760.

- ^ Hernández, Rubén; Guerrero, Clara; Palomino, Jesús (2008). "Palenque: historia libertaria, cultura y tradición". Grupo de Investigación Muntú.

- ^ Lipski, John M. (2020-06-03). "What you hear is (not always) what you get: Subjects and verbs among receptive Palenquero-Spanish bilinguals". Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism. 10 (3): 315–350. doi:10.1075/lab.17083.lip. ISSN 1879-9264. S2CID 149952479.

- ^ a b c d Mackenzie, Ian. "Palenquero".

- ^ McWhorter, John H. (2011-06-30). Linguistic Simplicity and Complexity: Why Do Languages Undress?. Walter de Gruyter. p. 92. ISBN 9781934078402.

- ^ Ledgeway, Adam; Maiden, Martin (2016-09-05). The Oxford Guide to the Romance Languages. Oxford University Press. p. 455. ISBN 9780191063251.

- ^ Moñino, Yves; Schwegler, Armin (2002-01-01). Palenque, Cartagena y Afro-Caribe: historia y lengua (in Spanish). Walter de Gruyter. p. 69. ISBN 9783110960228.

- ^ Moñino, Yves; Schwegler, Armin (2013-02-07). Palenque, Cartagena y Afro-Caribe: historia y lengua (in Spanish). Walter de Gruyter. p. 171. ISBN 9783110960228.

External links

edit- Colombian varieties of Spanish by Richard J. File-Muriel, Rafael Orozco (eds.), (2012)

- Misa andi lengua ri palenque - Katajena, mayo 21 ri 2000