Ioannina (Greek: Ιωάννινα Ioánnina [i.oˈa.ni.na] ), often called Yannena (Γιάννενα Yánnena [ˈʝa.ne.na]) within Greece, is the capital and largest city of the Ioannina regional unit and of Epirus, an administrative region in northwestern Greece. According to the 2021 census, the city population was 64,896 while the municipality had 113,978 inhabitants. It lies at an elevation of approximately 500 metres (1,640 feet) above sea level, on the western shore of Lake Pamvotis (Παμβώτις). Ioannina is located 410 km (255 mi) northwest of Athens, 260 kilometres (162 miles) southwest of Thessaloniki and 80 km (50 miles) east of the port of Igoumenitsa on the Ionian Sea.

Ioannina

Ιωάννινα | |

|---|---|

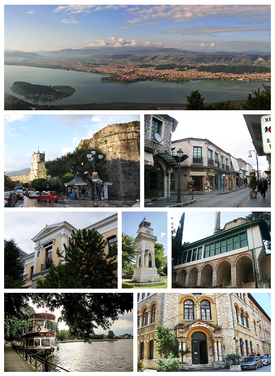

Clockwise from top: Panoramic view of Lake Pamvotis and the city of Ioannina from Mitsikeli, Old Town, Municipal Clock Tower of Ioannina, Municipal Ethnographic Museum of Ioannina, Kaplaneios School, Ferry to the Island, Post Office, and the Castle of Ioannina. | |

| Coordinates: 39°39′49″N 20°51′08″E / 39.66361°N 20.85222°E | |

| Country | Greece |

| Administrative region | Epirus |

| Regional unit | Ioannina |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Thomas Begkas[1] (since 2023) |

| Area | |

• Municipality | 403.32 km2 (155.72 sq mi) |

| • Municipal unit | 47.44 km2 (18.32 sq mi) |

| • Community | 17.355 km2 (6.701 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 480 m (1,570 ft) |

| Population (2021)[2] | |

• Municipality | 113,978 |

| • Density | 280/km2 (730/sq mi) |

| • Municipal unit | 81,627 |

| • Municipal unit density | 1,700/km2 (4,500/sq mi) |

| • Community | 64,896 |

| • Community density | 3,700/km2 (9,700/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Yanniote (Gianniote)/ Ioannite (formal) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal code | 45x xx |

| Area code(s) | 26510 |

| Vehicle registration | ΙΝ |

| Website | ioannina |

The city's foundation has traditionally been ascribed to the Byzantine Emperor Justinian in the 6th century AD, but modern archaeological research has uncovered evidence of Hellenistic settlements. Ioannina flourished in the late Byzantine period (13th–15th centuries). It became part of the Despotate of Epirus following the Fourth Crusade and many wealthy Byzantine families fled there following the 1204 sack of Constantinople, with the city experiencing great prosperity and considerable autonomy, despite the political turmoil. Ioannina surrendered to the Ottomans in 1430 and until 1868 it was the administrative center of the Pashalik of Yanina. In the period between the 18th and 19th centuries, the city was a major center of the modern Greek Enlightenment.[3][4][5][6] Ioannina was ceded to Greece in 1913 following the Balkan Wars.

The city is also characterized by various green areas and parks, including Molos (Lake Front), Litharitsia Park, Pirsinella Park (Giannotiko Saloni), Suburban Forest. There are two hospitals, the General Hospital of Ioannina "G. Hatzikosta", and the University Hospital of Ioannina. It is also the seat of the University of Ioannina. The city's emblem consists of the portrait of the Byzantine Emperor Justinian crowned by a stylized depiction of the nearby ancient theater of Dodona.

Name

editThe city's formal name, Ioannina, is probably a corruption of Agioannina or Agioanneia, 'place of St. John', and is said to be linked to the establishment of a monastery dedicated to Saint John the Baptist, around which the later settlement (in the area of the current Ioannina Castle) grew.[7][8]

According to another theory, the city was named after Ioannina, the daughter of Belisarius, general of the emperor Justinian.[9][10]

There are two forms of the name in Greek, Ioannina being the formal and historical name, while the colloquial and much more commonly used Υannena or Υannina (Greek: Γιάννενα, Γιάννινα) represents the vernacular tradition of Demotic Greek. The demotic form also corresponds to those in the neighboring languages (e.g., Albanian: Janina or Janinë, Aromanian: Ianina, Enina or Enãna, Macedonian: Јанина, Turkish: Yanya).

History

editAntiquity and early Middle Ages

editThe first indications of human presence in Ioannina basin are dated back to the Paleolithic period (24,000 years ago) as testified by findings in the cavern of Kastritsa.[11] During classical antiquity the basin was inhabited by the Molossians and four of their settlements have been identified there. Despite the extensive destruction suffered in Molossia during the Roman conquest of 167 BC, settlement continued in the basin albeit no longer in an urban pattern.[12]

The exact time of Ioannina's foundation is unknown, but it is commonly identified with an unnamed new, "well-fortified" city, recorded by the historian Procopius as having been built by the Byzantine emperor Justinian I for the inhabitants of ancient Euroia.[13][14] This view is not supported, however, by any concrete archaeological evidence.[15] Early 21st-century excavations have brought to light fortifications dating to the Hellenistic period, the course of which was largely followed by later reconstruction of the fortress in the Byzantine and Ottoman periods. The identification of the site with one of the ancient cities of Epirus has not yet been possible.[15][16]

It is not until 879 that the name Ioannina appears for the first time, in the acts of the Fourth Council of Constantinople, which refer to one Zacharias, Bishop of Ioannine, a suffragan of Naupaktos.[14] After the Byzantine conquest of Bulgaria, in 1020 Emperor Basil II subordinated the local bishopric to the Archbishopric of Ohrid.[14] The Greek archaeologist K. Tsoures dated the Byzantine city walls and the northeastern citadel of the Ioannina Castle to the 10th century, with additions in the late 11th century, including the south-eastern citadel, traditionally ascribed to the short-lived occupation of the city by the Normans under the leadership of Bohemond of Taranto in 1082.[15][17] In a chrysobull to the Venetians in 1198, the city is listed as part of its own province (provincia Joanninorum or Joaninon).[18] In the treaty of partition of the Byzantine lands after the Fourth Crusade, Ioannina was promised to the Venetians, but in the event, it became part of the new state of Epirus, founded by Michael I Komnenos Doukas.[18]

Late Middle Ages (1204–1430)

editUnder Michael I, the city was enlarged and fortified anew.[18] The Metropolitan of Naupaktos, John Apokaukos, reports how the city was but a "small town", until Michael gathered refugees who had fled Constantinople and other parts of the Empire that fell to the crusaders of the Fourth Crusade, and settled them there, transforming the city into a fortress and "ark of salvation". Despite frictions with local inhabitants who tried in 1232 to expel the refugees, the latter were eventually successfully settled and Ioannina gained in both population and economic and political importance.[19][20] In the aftermath of the Battle of Pelagonia in 1259, much of Epirus was occupied by the Empire of Nicaea, and Ioannina was placed under siege. Soon, however, the Epirote ruler Michael II Komnenos Doukas, aided by his younger son John I Doukas, managed to recover their capital of Arta and relieve Ioannina, evicting the Nicaeans from Epirus.[18][21] In c. 1275 or c. 1285, John I Doukas, now ruler of Thessaly, launched a raid against the city and its environs, and a few years later an army from the restored Byzantine Empire unsuccessfully laid siege to the city.[18][22][23] Following the assassination in 1318 of the last native ruler, Thomas I Komnenos Doukas, by his nephew Nicholas Orsini, the city refused to accept the latter and turned to the Byzantines for assistance. On this occasion, Emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos elevated the city to a metropolitan bishopric, and in 1319 issued a chrysobull conceding wide-ranging autonomy and various privileges and exemptions on its inhabitants.[18][24] A Jewish community is also attested in the city in 1319.[25] In the Epirote revolt of 1337–1338 against Byzantine rule, the city remained loyal to Emperor Andronikos III Palaiologos.[18] Soon afterwards Ioannina fell to the Serb ruler Stephen Dushan and remained part of the Serbian Empire until 1356, when Dushan's half-brother Simeon Uroš was evicted by Nikephoros II Orsini. The attempt of Nikephoros to restore the Epirote state was short-lived as he was killed in the Battle of Achelous against Albanian tribes.,[26][27] but Ioannina was not captured. It thus served as a place of refuge for many Greeks of the region of Vagenetia.[28][29] In 1366–67 Simeon Uroš, having recovered Epirus and Thessaly, appointed his son-in-law Thomas II Preljubović as the new overlord of Ioannina. Thomas proved a deeply unpopular ruler, but he nonetheless repelled successive attempts by Albanian chieftains including a surprise attack in 1379, whose failure the Ioannites attributed to intervention by their patron saint, Michael.[30][31]

After Thomas' murder in 1384, the citizens of Ioannina offered their city to Esau de' Buondelmonti, who married Thomas' widow, Maria. Esau recalled those exiled under Thomas and restored the properties confiscated by him. In 1389, Ioannina was besieged by Gjin Bua Shpata, and only with the aid of an Ottoman army was Esau able to repel the Albanians. Despite the ongoing Ottoman expansion and the conflicts between Turks and Albanians in the vicinity of Ioannina, Esau managed to secure a period of peace for the city, especially following his second marriage to Shpata's daughter Irene in c. 1396. Following Esau's death in 1411, the Ioannites invited the Count palatine of Cephalonia and Zakynthos, Carlo I Tocco, who had already been expanding his domains into Epirus for the last decade, as their new ruler. By 1416 Carlo I Tocco had managed to capture Arta as well, thereby reuniting the core of the old Epirote realm, and received recognition from both the Ottomans and the Byzantine emperor. Ioannina became the summer capital of the Tocco domains, and Carlo I died there in July 1429.[32] Carlo I's army, as well as the army of the city of Ioannina itself both before and during Carlo I's rule, was composed primarily of Albanians.[33] His oldest bastard son, Ercole, called on the Ottomans for aid against the legitimate heir, Carlo II Tocco. In 1430 an Ottoman army, fresh from the capture of Thessalonica, appeared before Ioannina. The city surrendered after the Ottoman commander, Sinan Pasha, promised to spare the city and respect its autonomy.[34]

Ottoman period (1430–1913)

editUnder Ottoman rule, Ioannina remained an administrative centre, as the seat of the Sanjak of Ioannina, and experienced a period of relative stability and prosperity.[8] The first Ottoman tax registers for the city dates to 1564, and records 50 Muslim households and 1,250 Christian ones; another register from 15 years later mentions Jews as well.[8]

In 1611 the city suffered a serious setback as a result of a peasant revolt led by Dionysius the Philosopher, the Metropolitan of Larissa. The Greek inhabitants of the city were unaware of the intent of the fighting as previous successes of Dionysius had depended on the element of surprise. Much confusion ensued as Turks and Christians ended up indiscriminately fighting friend and foe alike. The revolt ended in the abolition of all privileges granted to the Christian inhabitants, who were driven away from the castle area and had to settle around it. From then onwards, Turks and Jews were to be established in the castle area. The School of the Despots at the Church of the Taxiarchs, that had been operating since 1204, was closed. Aslan Pasha also destroyed the monastery of St. John the Baptist within the city walls in 1618 erected in its place the Aslan Pasha Mosque, today housing the Municipal Ethnographic Museum of Ioannina.[35] The Ottoman reprisals in the wake of the revolt included the confiscation of many timars previously granted to Christian sipahis; this began a wave of conversions to Islam by the local gentry, who became the so-called Tourkoyanniotes (Τoυρκογιαννιώτες).[8] The Ottoman traveller Evliya Çelebi, who visited the city in c. 1670, counted 37 quarters, of which 18 Muslim, 14 Christian, 4 Jewish and 1 Gypsy. He estimated the population at 4,000 hearths.[8]

Center of Greek Enlightenment (17th–18th centuries)

editDespite the repression and conversions in the 17th century, and the prominence of the Muslim population in the city's affairs, Ioannina retained its Christian majority throughout Ottoman rule, and the Greek language retained a dominant position; Turkish was spoken by the Ottoman officials and the garrison, and the Albanian inhabitants used Albanian, but the lingua franca and native language of most inhabitants was Greek, including among the Tourkoyanniotes, and was sometimes used by the Ottoman authorities themselves.[8]

The city also soon recovered from the financial effects of the revolt. In the late 17th century Ioannina was a thriving city with respect to population and commercial activity. Evliya Çelebi mentions the presence of 1,900 shops and workshops. The great economic prosperity of the city was followed by remarkable cultural activity. During the 17th and 18th centuries, many important schools were established.[36] Its inhabitants continued their commercial and handicraft activities which allowed them to trade with important European commercial centers, such as Venice and Livorno, where merchants from Ioannina established commercial and banking houses. The Ioannite diaspora was also culturally active: Nikolaos Glykys (in 1670), Nikolaos Sarros (in 1687) and Dimitrios Theodosiou (in 1755) established private printing presses in Venice, responsible for over 1,600 editions of books for circulation in the Ottoman-ruled Greek lands, and Ioannina was the centre through which these books were channeled into Greece.[37] These were significant historical, theological as well as scientific works, including an algebra book funded by the Zosimades brothers, books for use in the schools of Ioannina such as the Arithmetica of Balanos Vasilopoulos, as well as medical books. At the same time these merchants and entrepreneurs maintained close economic and intellectual relations with their birthplace and founded charity and education establishments. These merchants were to be major national benefactors.

Thus the Epiphaniou School was founded in 1647 by a Greek merchant of Ioannite origin resident in Venice, Epiphaneios Igoumenos.[38] The Gioumeios School was founded in 1676 by a benefaction from another wealthy Ioannite Greek from Venice, Emmanuel Goumas. It was renamed Balaneios by its rector, Balanos Vasilopoulos, in 1725. Here worked several notable personalities of the Greek Enlightenment, such as Bessarion Makris, the priests Georgios Sougdouris (1685/7–1725) and Anastasios Papavasileiou (1715–?), the monk Methodios Anthrakites, his student Ioannis Vilaras and Kosmas Balanos. The Balaneios taught philosophy, theology and mathematics. It suffered financially from the dissolution of the Republic of Venice by the French and finally stopped operation in 1820. The school's library, which hosted several manuscripts and epigrams, was also burned the same year following the capture of Ioannina by the troops the Sultan had sent against Ali Pasha.[39] The Maroutses family, also active in Venice, founded the Maroutsaia School, which opened in 1742 and its first director Eugenios Voulgaris championed the study of the physical sciences (physics and chemistry) as well as philosophy and Greek. The Maroutsaia also suffered after the fall of Venice and closed in 1797 to be reopened as the Kaplaneios School thanks to a benefaction from an Ioannite living in Russia, Zoes Kaplanes. Its schoolmaster, Athanasios Psalidas had been a student of Methodios Anthrakites and had also studied in Vienna and in Russia. Psalidas established an important library of thousands of volumes in several languages and laboratories for the study of experimental physics and chemistry that aroused the interest and suspicion of Ali Pasha. The Kaplaneios was burned down along with most of the rest of the city after the entry of the Sultan's armies in 1820. These schools took over the long tradition of the Byzantine era, giving a significant boost to the Greek Enlightenment. "During the 18th century", Neophytos Doukas wrote with some exaggeration, "every author of the Greek world, was either from Ioannina or was a graduate of one of the city's schools."[40]

Ali Pasha's rule (1788–1822)

editIn 1788 the city became the center of the territory ruled by Ali Pasha, an area that included the entire northwestern part of Greece, southern parts of Albania, Thessaly as well as parts of Euboea and the Peloponnese. The Ottoman-Albanian lord Ali Pasha was one of the most influential personalities of the region in the 18th and 19th centuries. Born in Tepelenë, he maintained diplomatic relations with the most important European leaders of the time and his court became a point of attraction for many of those restless minds who would become major figures of the Greek Revolution (Georgios Karaiskakis, Odysseas Androutsos, Markos Botsaris and others). During this time, however, Ali Pasha committed a number of atrocities against the Greek population of Ioannina, culminating in the sewing up of local women in sacks and drowning them in the nearby lake,[41] this period of his rule coincides with the greatest economic and intellectual prosperity of the city. As a couplet has it "The city was first in arms, money and letters".

When the French scholar François Pouqueville visited the city during the early years of the 19th century, he counted 3,200 homes (2,000 Christian, 1,000 Muslim, 200 Jewish).[8] The efforts of Ali Pasha to break away from the Sublime Porte alarmed the Ottoman government, and in 1820 (the year before the Greek War of Independence began) he was declared guilty of treason and Ioannina was besieged by Turkish troops. Ali Pasha was assassinated in 1822 in the monastery of St Panteleimon on the island of the lake, where he took refuge while waiting to be pardoned by Sultan Mahmud II.[42]

Last Ottoman century (1822–1913)

editThe Zosimaia was the first significant educational foundation established after the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence (1828). It was financed by a benefaction from the Zosimas brothers and began operating in 1828 and fully probably from 1833.[43] It was a School of Liberal Arts (Greek, Philosophy and Foreign Languages). The mansion of Angeliki Papazoglou became the Papazogleios school for girls as an endowment following her death; it operated until 1905.

In 1869, a great part of Ioannina was destroyed by fire. The marketplace was soon reconstructed according to the plans of the German architect Holz, thanks to the personal interest of Ahmet Rashim Pasha, the local governor. Communities of people from Ioannina living abroad were active in financing the construction of most of the city's churches, schools and other elegant buildings of charitable establishments. The first bank of the Ottoman Empire, the Ottoman Bank, opened its first branch in Greece[clarification needed] in Ioannina, which shows the power of the city in world trade in the 19th century. As the 19th century came to a close, signs of national agitation emerged among some parts of the city' s population. In 1877 for example, Albanian leaders sent a memorandum to the Ottoman government demanding, among other things, the establishment of Albanian language schools and various Muslim Albanians of the Vilayet formed in Ioannina a committee which aimed at defending Albanian rights, but it was inactive in general.[44][45][46][47] The Greek population of the region authorized a committee to present to European governments their wish for union with Greece; as a result Dimitrios Chasiotis published a memorandum in Paris in 1879.[48]

According to the Ottoman censuses of 1881–1893, the city and its environs (the central kaza of the Sanjak of Ioannina), had a population comprising 4,759 Muslims, 77,258 Greek Orthodox (including both Greek and Albanian speakers), 3,334 Jews and 207 of foreign nationality.[8] While a number of Turkish-language schools were established at the time, Greek-language education retained its prominent position. Even the city's prominent Muslim families preferred to send their children to well-established Greek institutions, notably the Zosimaia. As a result, the dominance of the Greek language in the city continued: the minutes of the city council were kept in Greek, and the official newspaper, Vilayet, established in 1868, was bilingual in Turkish and Greek.[8]

By 1908 an Albanian association was already active in Ioannina with the goal of removing the Albanian schools and churches of Ioaninna from the Greek's Patriarchate sphere of influence.[49]

During the Ottoman period (turcokracy) the religious-linguistic minority of "Turco-yanniotes" (Τουρκογιαννιώτες) existed in Ioannina and neighbouring areas. These were islamized "Yaniotes" (= people from Ioannina), who spoke Greek. There is a limited number of texts written with Greek alphabet in their idiom.[50]

Modern period (since 1913)

editIoannina was incorporated into the Greek state on 21 February 1913 after the Battle of Bizani in the First Balkan War. The day the city came under the control of the Greek forces, aviator Christos Adamidis, a native of the city, landed his Maurice Farman MF.7 biplane in the Town Hall square, to the adulation of an enthusiastic crowd.[51]

Following the Asia Minor Catastrophe (1922) and the Treaty of Lausanne, the Muslim population was exchanged with Greek refugees from Asia Minor. A small Muslim community of Albanian origin continued to live in Ioannina after the exchange, which in 1940 counted 20 families and had decreased to 8 individuals in 1973.[52]

In 1940 during World War II the capture of the city became one of the major objectives of the Italian Army. Nevertheless, the Greek defense in Kalpaki pushed back the invading Italians.[53] In April 1941 Ioannina was intensively bombed by the German forces even during the negotiations that led to the capitulation of the Greek army.[54] During the subsequent Axis occupation of Greece, the city's Jewish community was rounded up by the Germans in 1944 and mostly perished in the concentration camps.[8] On 3 October 1943, the German army murdered in reprisal nearly 100 people in the village of Lingiades, 13 kilometres distant from Ioaninna, in what is known as the Lingiades massacre.

The University of Ioannina was founded in 1970; until then, higher education faculties in the city had been part of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki.[55]

Jewish community

editAccording to the local Greek scholar Panayiotis Aravantinos, a synagogue destroyed in the 18th century bore an inscription which dated its foundation in the late 9th century AD.[56] The existing synagogue was built in 1829 and is known as the Old Synagogue. It is located in the old fortified part of the city known as "Kastro", at 16 Ioustinianou street. Its architecture is typical of the Ottoman era, a large building made of stone. The interior of the synagogue is laid out in the Romaniote way: the bimah (where the Torah scrolls are read out during service) is on a raised dais on the western wall, the Aron haKodesh (where the Torah scrolls are kept) is on the eastern wall and at the middle there is a wide interior aisle. The names of the Ioanniote Jews who were killed in the Holocaust are engraved in stone on the walls of the synagogue.

There was a Romaniote Jewish community living in Ioannina before World War II, in addition to a very small number of Sephardi. Many emigrated to New York, founding a congregation in 1906 and the Kehila Kedosha Janina synagogue in 1927.

According to Rae Dalven,[citation needed] 1,950 Jews were living in Ioannina in April 1941. Of these, 1,870 were deported by the Nazis to concentration camps on 25 March 1944, during the final months of German occupation.[57] Almost all of the people deported were murdered on or shortly after 11 April 1944, when the train carrying them reached Auschwitz-Birkenau. Only 181 Ioannina Jews are known to have survived the war, including 112 who survived Auschwitz and 69 who fled to join the resistance leader Napoleon Zervas and the National Republican Greek League (EDES). Approximately 164 of these survivors eventually returned to Ioannina.[58]

As of 2008, the remaining community has shrunk to about 50 mostly elderly people.[59][60] The Kehila Kedosha Yashan Synagogue remains locked, only opened for visitors on request. Emigrant Romaniotes return every summer and open the old synagogue. The last time a Bar Mitzvah (the Jewish ritual for celebrating the coming of age of a child) was held in the synagogue was in 2000, and was an exceptional event for the community.[61] A monument dedicated to the thousands of Greek Jews who perished during the Holocaust was constructed in the city in a 13th-century Jewish cemetery. In 2003 the memorial was vandalized by unknown anti-Semites.[62] The Jewish cemetery too was repeatedly vandalized in 2009.[63] As a response to the vandalisms, citizens of the city formed an initiative for the protection of the cemetery and organized rallies.[64]

In the municipal election of 2019, independent candidate Moses Elisaf, a 65-year-old doctor, was elected mayor of the city, the first Jewish elected mayor in Greece. Elisaf won 50.3 percent of the vote. Elisaf received 17,789 votes, 235 more than his runoff opponent.[65][66][67]

Geography

editIoannina lies at an elevation of approximately 500 metres (1,640 feet) above sea level, on the western shore of Lake Pamvotis (Παμβώτις). It is located within the Ioannina municipality, and is the capital of Ioannina regional unit and the region of Epirus. Ioannina is located 436 km (271 mi) northwest of Athens, 290 kilometres (180 miles) southwest of Thessaloniki and 90 km (56 miles) east of the port of Igoumenitsa in the Ionian Sea.

The municipality Ioannina has an area of 403.322 km2, the municipal unit Ioannina has an area of 47.440 km2, and the community Ioannina (the city proper) has an area of 17.335 km2.[68]

Districts

editThe present municipality Ioannina was formed at the 2011 local government reform by the merger of the following 6 former municipalities, that became municipal units (constituent communities in brackets):[69]

- Ioannina (Ioannina, Exochi, Marmara, Neochoropoulo, Stavraki)

- Anatoli (Anatoli, Bafra, Neokaisareia)

- Bizani (Ampeleia, Bizani, Asvestochori, Kontsika, Kosmira, Manoliasa, Pedini)

- Ioannina Island (Greek: Nisos Ioanninon)

- Pamvotida (Katsikas, Anatoliki, Vasiliki, Dafnoula, Drosochori, Iliokali, Kastritsa, Koutselio, Krapsi, Longades, Mouzakaioi, Platania, Platanas, Charokopi)

- Perama (Perama, Amfithea, Kranoula, Krya, Kryovrysi, Ligkiades, Mazia, Perivleptos, Spothoi)

Climate

editIoannina has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Csa) or a humid subtropical climate (Cfa) in the Köppen climate classification, with somewhat wetter summers than nearby coastal areas, tempered by its inland location and elevation. Summers are typically hot and moderately dry, while winters are wet and colder than on the coast with frequent frosts and occasional snowfall. Ioannina is the wettest city in mainland Greece with over 50,000 inhabitants.[citation needed] The absolute maximum temperature ever recorded was 42.4 °C (108 °F), while the absolute minimum ever recorded was −13 °C (9 °F).[70]

| Climate data for Ioannina (475 m; 1956–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 9.0 (48.2) |

10.4 (50.7) |

13.7 (56.7) |

17.5 (63.5) |

23.0 (73.4) |

27.7 (81.9) |

31.0 (87.8) |

31.0 (87.8) |

26.1 (79.0) |

20.6 (69.1) |

14.7 (58.5) |

10.0 (50.0) |

20.0 (68.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.7 (40.5) |

6.1 (43.0) |

8.8 (47.8) |

12.4 (54.3) |

17.4 (63.3) |

21.9 (71.4) |

24.8 (76.6) |

24.3 (75.7) |

20.1 (68.2) |

14.9 (58.8) |

9.7 (49.5) |

5.9 (42.6) |

14.3 (57.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 0.2 (32.4) |

1.0 (33.8) |

3.2 (37.8) |

6.1 (43.0) |

9.8 (49.6) |

13.0 (55.4) |

15.2 (59.4) |

15.3 (59.5) |

12.2 (54.0) |

8.6 (47.5) |

4.8 (40.6) |

1.7 (35.1) |

7.5 (45.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 122.5 (4.82) |

112.5 (4.43) |

94.9 (3.74) |

76.5 (3.01) |

66.9 (2.63) |

44.1 (1.74) |

31.7 (1.25) |

30.2 (1.19) |

62.4 (2.46) |

107.5 (4.23) |

168.8 (6.65) |

171.3 (6.74) |

1,089.3 (42.89) |

| Average precipitation days | 13.3 | 12.4 | 12.8 | 12.6 | 11.0 | 6.9 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 6.5 | 9.7 | 13.7 | 15.2 | 123.7 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76.9 | 73.7 | 69.5 | 67.9 | 65.9 | 59.1 | 52.4 | 54.4 | 63.6 | 70.8 | 79.8 | 81.5 | 68.0 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 95.3 | 107.9 | 143.4 | 165.2 | 225.2 | 296.0 | 320.7 | 296.0 | 208.2 | 160.4 | 98.1 | 75.2 | 2,191.6 |

| Source: Greek National Weather Service[71] | |||||||||||||

Demography

editAccording to the 2021 census the resident population fell by 4.2%. Men constitute 48.9% and women 51.1% of the total population.[72]

| Year | Town | Municipal unit | Municipality | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1913[73] | 16,804 | – | – | ||

| 1920[74] | 20,765 | – | – | ||

| 1928[75] | 20,485 | – | – | ||

| 1940[76] | 21,887 | – | – | ||

| 1951[77] | 32,315 | – | – | ||

| 1961[78] | 34,997 | – | – | ||

| 1971[79] | 40,130 | – | – | ||

| 1981[80] | 44,829 | – | – | ||

| 1991[81] | 56,699 | – | – | ||

| 2001[82] | 67,384 | – | 75,550 | ||

| 2011 | 65,574 | 80,371 | 112,486[72] | 53,975 | 58,511 |

| 2021 | 64,896 | 81,627 | 113,978[72] | 54,951 | 59,027 |

Landmarks and sights

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2017) |

Isle of Lake Pamvotis

editOne of the most notable attractions of Ioannina is the inhabited island of Lake Pamvotis which is simply referred to as Island of Ioannina. The island is a short ferry trip from the mainland and can be reached on small motorboats running on varying frequencies depending on the season. The monastery of St Panteleimon, where Ali Pasha spent his last days waiting for a pardon from the Sultan, is now a museum housing everyday artefacts and relics of his period.[83] There are six monasteries on the island: the monastery of St Nicholas (Ntiliou) or Strategopoulou (11th century), the Monastery of St Nicholas (Spanou) or Philanthropinon (1292), St John the Baptist (1506), Eleousis (1570), St Panteleimon (17th century), and of the Transfiguration of Christ (1851). The monasteries of Strategopoulou and Philanthropinon also functioned as colleges. Alexios Spanos, the monks Proklos and Comnenos, and the Apsarades brothers Theophanis and Nektarios are among those that taught there.[35] The school continued its activities until 1758, when it was superseded by the newer collegial institutions within the city. The island's winding streets are also home to many gift-shops, tavernas, churches and bakeries.

Ioannina Castle

editAt the south-eastern edge of the town on a rocky peninsula of Lake Pamvotis, the castle was the administrative heart of the Despotate of Epirus, and the Ottoman vilayet. The castle was in constant use until the late Ottoman period and the fortifications underwent several modifications throughout the centuries. The most extensive alterations where conducted during the rule of Ali Pasha and were completed in 1815.[84] Several monuments such as the Byzantine baths, the Ottoman baths, the Ottoman library, and the Soufari Sarai are found within the castle's walls.[85] There are two citadels in the castle. The south-eastern citadel, which bears the name Its Kale (Ιτς Καλέ, from Turkish Iç Kale, 'inner fortress')[citation needed] is where the Fethiye Mosque, the tomb of Ali Pasha, and the Byzantine Museum are located.[86] The north-eastern citadel is dominated by the Aslan Pasha Mosque and also contains a few other monuments dating from the Ottoman period.[86] The old Jewish Synagogue of Ioannina is within the walls of the castle and is one of the oldest and largest buildings of its type surviving in Greece.[87][86]

The city

editSeveral religious and secular monuments survive from the Ottoman period. In addition to the two mosques surviving within the walls of the castle, two further mosques are preserved outside the walls. The Mosque and Madrassa of Veli Pasha are in the centre of the city,[88] and Kaloutsiani Mosque can be found in the area of the city with the same name.[89] The now derelict "House of the Archbishop", near the football stadium, is the only old mansion that survived the fire of 1820.[90] Some of the notable landmarks in the city centre also date from the late Ottoman period. The municipal clock tower of Ioannina, designed by local architect Periklis Meliritos, was erected in 1905 to celebrate the Jubilee of sultan Abdul Hamid II. The adjacent building houses the VIII Division headquarters. It dates from the late 19th century.[91][92] Some neoclassical buildings such the post office, the old Zosimaia School, the Papazogleios Weaving School, and the former Commercial School date from the late Ottoman period as do a few arcades in the old commercial centre of the city like Stoa Louli and Stoa Liampei.[93] The churches of the Assumption of the Virgin at Perivleptos, Saint Nicholas of Kopanon and Saint Marina were rebuilt in the 1850s by funds from Nikolaos Zosimas and his brothers on the foundations of previous churches that perished in the great fire of 1820. The Cathedral of St Athanasius was completed in 1933. It was built on the foundations of the previous Orthodox cathedral which was destroyed in the fires of 1820. It is a three-aisled basilica.

Culture

editMuseums and galleries

editSome of the most important museums of the city are within the walls of the castle. The Municipal Ethnographic Museum is hosted in Aslan Pasha Mosque in the north-east citadel. It is divided into three departments, each one representing one of the main communities that inhabited the city: Greek, Muslim, and Jewish.[94] The Byzantine Museum is in the south-eastern citadel of the castle. The museum opened in 1995 in order to preserve and present artefacts of the wider region of Epirus covering the period from the 4th to the 19th century.[95] The newest addition to the city's museum, the silversmithing museum, is also in the south-eastern citadel. It is housed in the western bastion of the citadel and outlines the history of the art of silversmithing in Epirus.[96] Outside the walls of the castle, close to the town centre, one will find the Archaeological Museum of Ioannina. It is in the Litharitsia fortress area. It includes archaeological exhibits documenting the human habitation of Epirus from prehistoric times through the late Roman Period, with special emphasis placed on finds from the Dodona sanctuary.[97] The Municipal Art Gallery of Ioannina (Dimotiki Pinakothiki) is housed in the Pyrsinella neoclassical building dating from around 1890. The gallery's collection displays major modern works of painters and sculptors, collected through purchases and donations from various collectors and artists. This includes about 500 works, paintings, drawings, prints, pictures and sculptures.[98] The Pavlos Vrellis Greek History Museum is 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) south of the city. It is a wax museum which covers events and personalities from Greek history as well as the history of the region and is the result of the personal work of Pavlos Vrellis.[99]

Exhibitions

editA digital art exhibition, Plásmata II, was organised by the Onassis Cultural Center in the lakeside of Pamvotis, in the summer of 2023.[100] More than 100,000 people visited the exhibition.[101] It is a new entry for the city and future actions in every area with the help of Onassis Cultural Center.[102]

Education

editThe University of Ioannina (Greek: Πανεπιστήμιο Ιωαννίνων, Panepistimio Ioanninon) is a university five kilometres southwest of Ioannina. The university was founded in 1964, as a charter of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and became an independent university in 1970. Today, the university is one of the leading academic institutions in Greece.[103][104][105][106][107]

As of 2017, there was a student population of 25,000 enrolled at the university (21,900 at the undergraduate level and 3,200 at the postgraduate level) and 580 faculty members, while teaching is further supplemented by 171 teaching fellows and 132 laboratory staff. The university administrative services are staffed with 420 employees.[108][109]

Local products

edit- Ioannina is known throughout Greece for its silverwork, with a number of shops selling silver jewelry, bronzeware, and decorative items (serving trays, recreations of shields and swords.)

- Hookahs (nargiles, ναργιλές) are sold to tourists as novelty items and vary in size from small (three inches in height) to quite large (4–5 ft (1–2 m) tall).

Cuisine

editMedia

edit- Epirus TV1

- Ipirotikos Agon, a locally published newspaper

- Proinos Logos, a locally published newspaper

Technology hub development

editBeginning in the early 2020s, Ioannina has started to evolve into a significant technology hub. The city has attracted technology companies, which have helped to bolster Ioannina's technological capacity and contributed to a new economic trajectory for the city, driving development in this sector.[112]

Additionally, the prefecture has been actively fostering partnerships between Greek and German companies in a bid to further strengthen the local economy and tech ecosystem. A Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) was signed with the Greek-German Chamber, outlining the recovery plan for the region, a move that has been seen as a significant step in boosting technological development in Ioannina.[113]

Consulates

editThe city hosts consulates from the following countries:

Ioannina compromise

editAn informal meeting of the foreign ministers of the states of the European Union took place in Ioannina on 27 March 1994, resulting in the Ioannina compromise.

Notable people from Ioannina

edit- Michael Apsaras, 14th century, Greek noble.

- Simon Strategopoulos 15th-century, noble and governor of Ioannina.[114]

- Epifanios Igoumenos (1568–1648), scholar.[115]

- Nikolaos Glykys (1619–1693), merchant and book publisher.[116]

- Nikolaos Sarros (1617–1697), book publisher, owner of one of the first Greek printing-houses in Venice[117]

- Bessarion Makris (1635–1699), scholar.

- Georgios Sougdouris (1645/7–1725), scholar.

- Methodios Anthrakites (1660–1736), scholar.

- Balanos Vasilopoulos (1694–1760), scholar.

- Dimitrios Theodosiou (-1782), book publisher.[118]

- Zosimades brothers, benefactors, founders of the Zosimaia School.

- Maroutsis family, traders and benefactors.[38]

- Kyra Frosini (1772–1800), socialite and heroine.

- Lambros Photiadis (1752–1805), scholar.

- Zois Kaplanis (1736-1806), merchant, founder of the Kaplaneios School

- Kosmas Balanos (1731–1808), scholar.

- Grigorios Paliouritis (1778–1816), scholar.[119]

- Ioannis Vilaras (1771–1823), poet and scholar.

- Athanasios Psalidas (1767–1829), scholar, of the main contributors of the Modern Greek Enlightenment.

- Georgios Hadjikonstas (1753–1845), benefactor.[120]

- Vasileios Goudas (1779–1845), fighter of the Greek War of Independence.

- Athanasios Tsakalov (1790–1851), one of the three founders of Filiki Eteria.

- Michael Christaris (1773–1851), scholar.[121]

- Elisabeth Kastrisogia (1800–1863), benefactor.[122]

- Georgios Stavros (1787–1869), benefactor, founder of the National Bank of Greece.

- Leonidas Palaskas (1819–1880), Hellenic navy officer.

- Reshid Akif Pasha (1863-1920), Ottoman statesman.

- Georgios Hatzis (Pelleren) (1881–1930), author and journalist.

- Josef Elijia (1901–1931), Jewish Greek poet.[123]

- Patriarch Nicholas V of Alexandria (1876–1939)[124]

- Wehib Pasha (1877–1940), Ottoman general.

- Christos Adamidis (1885–1949), pioneer aviator and Hellenic Army General.

- Mid'hat Frashëri (1880–1949), politician and writer.

- Mehmet Esat Bülkat (1862–1952), Ottoman general.

- İzzettin Çalışlar (1882–1951), officer of the Ottoman Army.

- Abdülhalik Renda (1881-1957), Chairman of the Turkish National Assembly.

- Markos Avgeris (1884–1973), poet.

- Amalia Bakas (1897–1979), singer.[125]

- Dimitrios Hatzis (1913–1981), novelist.[126]

- Dimosthenis Kokkinos (1926–1991), Poet and author.

- Fatma Hikmet İşmen (1918-2006), engineer.

- Pavlos Vrellis (1922–2010), sculptor.

- Dinos Constantinides (1929–2021), classical music composer.

- Takis Mousafiris (1936–2021), Greek composer and songwriter[127]

- Matsas family, Romaniote Jewish family; most known Minos Matsas

- Hierotheos (Vlachos), theologian.

- Moses Elisaf (1954–2023), mayor from 2019 to 2023.

- Vana Barba, actress.

- Marios Oikonomou, international football player, played for PAS Giannina, AEK Athens and Italian clubs like Cagliari, Bologna, Bari, SPAL.

- Georgios Dasios played for PAS Giannina and became the Director of the club.[128]

- Stefanos Ntouskos (b. 1997), gold medal in the Men's single sculls, at the 2020 Summer Olympics.

- Amanda Tenfjord (b. 1997), singer and songwriter, Greek representative at Eurovision 2022

- Polychronis Tsigkas (b. 2000), Greek-Cypriot professional basketball player

Sports

editSport clubs

editIoannina is home to a major sports team called PAS Giannina. It's an inspiration for many of old as well as new supporters of the whole region of Epirus, even outside Ioannina. Rowing is also very popular in Ioannina; the lake hosted several international events and serves as the venue for part of the annual Greek Rowing Championships.

| Club | Founded | Sports | Achievements |

|---|---|---|---|

| NO Ioanninon | 1954 | Rowing | Long-time champions in Greece |

| Spartakos AO | 1984 | Olympic weightlifting, Judo, Track and field, Basketball | Long-time champions in Greece in weightlifting |

| PAS Giannina | 1966 | Football | Long-time presence in A Ethniki |

| AGS Giannena | 1963 | Basketball, Volleyball, Track and field | Earlier presence in A1 Ethniki volleyball |

| AE Giannena F.C. | 2004 | Football | Earlier presence in Gamma Ethniki |

| Giannena AS | 2014 | Volleyball | Presence in A2 Ethniki volleyball |

| Ioannina B.C. | 2015 | Basketball | Presence in B Ethniki |

| VIKOS FALCONS | 2021 | Basketball | Presence in B Ethniki |

Sport complex

edit| Club | Founded | Sports | Clubs: |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zosimades Stadium | 1952 | Football | PAS Giannina |

| Panepirotan | 2002 | Basketball, Volleyball, Track and field | PAS Giannina, AO Velissarios FC[129]AE Giannena |

Transport

edit- Ioannina is served by Ioannina National Airport.

- The A2 motorway (Egnatia Odos), part of the E90, passes by Ioannina. It links the west coast port of Igoumenitsa with the borders.

- Air Sea Lines flew from Lake Pamvotis to Corfu with seaplanes. Air Sea Lines has suspended flights from Corfu to Ioannina since 2007.

- Long-distance buses (KTEL) travel daily to Athens (6–6.5 hours) and Thessaloniki (3 hours).

In popular culture

edit- "Yanina" figures prominently in Alexandre Dumas' novel The Count of Monte Cristo.

- Villagers of Ioannina City is a folk rock band from Ioannina, formed in 2007.

International relations

editTwin towns – sister cities

editIoannina is twinned with:

See also

edit- Epirus

- Maroutsaia School

- Uprising in Yanina

- Zagori, region and municipality near Ioannina

- List of mayors of Ioannina

- Timeline of Ioannina

Citations

edit- ^ "Municipality of Ioannina, Municipal elections – October 2023". Ministry of Interior.

- ^ "Αποτελέσματα Απογραφής Πληθυσμού - Κατοικιών 2021, Μόνιμος Πληθυσμός κατά οικισμό" [Results of the 2021 Population - Housing Census, Permanent population by settlement] (in Greek). Hellenic Statistical Authority. 29 March 2024.

- ^ Sakellariou M. V. Epirus, 4000 years of Greek history and civilization Archived 30 September 2023 at the Wayback Machine. Ekdotikē Athēnōn, 1997, ISBN 978-960-213-371-2 p. 268

- ^ Fleming Katherine Elizabeth. The Muslim Bonaparte: diplomacy and orientalism in Ali Pasha's Greece. Princeton University Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0-691-00194-4. p. 63-66

- ^ The Era of Enlightenment (late 7th century – 1821) Archived 26 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Εθνικό Kέντρο Bιβλίου, p. 13

- ^ Υπουργείο Εσωτερικών, Αποκέντρωσης και Ηλεκρονικής Διακυβέρνησης Περιφέρεια Ηπείρου Archived 29 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine: "Στη δεκαετία του 1790 ο νεοελληνικός διαφωτισμός έφθασε στο κορύφωμά του. ΦορέαA_1του πνεύματος στα Ιωάννινα είναι ο Αθανάσιος ΨαλίδαA_."

- ^ Osswald, Brendan (2008). "From Lieux de Pouvoir to Lieux de Mémoire: The Monuments of the Medieval Castle of Ioannina through the Centuries". In Hálfdanarson, Gudmundur (ed.). Discrimination and tolerance in historical perspective. Pisa: PLUS-Pisa University Press. p. 188. ISBN 978-88-8492-558-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Anastassiadou 2002, pp. 282–283.

- ^ Charisis, Ch. (2019). "Το όνομα των Ιωαννίνων" [The name of the Ioannina]. Volume of Proceedings of the 3rd Panepirot Conference (in Greek). Janina: Society for Continental Studies and Foundation for Ionian and Adriatic Studies. Archived from the original on 30 September 2023. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- ^ "Πώς και από ποιον προήλθε το όνομα των Ιωαννίνων" [How and from whom came the name of Ioannina]. Ελευθερία (in Greek). January 2019. Archived from the original on 11 May 2022. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ Galanidou, N.; Tzedakis, P. C.; Lawson, I. T.; Frogley, M. R. (2000). "A revised chronological and palaeoenvironmental framework for the Kastritsa rockshelter, northwest Greece". Antiquity. 74 (284): 349–355. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00059421. S2CID 128085232.

- ^ Pliakou, G. (2013). "The Basin of Ioannina after the Roman Conquest. The Evidence of the Excavation Coins". In Liampi, K.; Papaevangelou-Genakos, C.; Zachos, K.; Dousougli, A.; Iakovidou, A. (eds.). Numismatic History and Economy in Epirus During Antiquity (in Greek). Athens: Proceedings of the 1st International conference: Numismatic History and Economy in Epirus During Antiquity (University of Ioannina, 3–7 October 2007). pp. 449–462.

- ^ Gregory 1991, p. 1006.

- ^ a b c Soustal & Koder 1981, p. 165.

- ^ a b c Κάστρο Ιωαννίνων: Περιγραφή (in Greek). Greek Ministry of Culture. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ Papadopoulou 2014, p. 4.

- ^ Soustal & Koder 1981, pp. 165–166.

- ^ a b c d e f g Soustal & Koder 1981, p. 166.

- ^ Osswald, Brendan (2007). "The Ethnic Composition of Medieval Epirus". In Ellis, Steven; Klusáková, Lud'a (eds.). Imagining Frontiers: Contesting Identities. Pisa: Edizioni Plus – Pisa University Press. p. 132.

- ^ Nicol, Donald MacGillivray (1976). "Refugees, Mixed Population and Local Patriotism in Epiros and Western Macedonia after the Fourth Crusade". XVe Congrès international d'études byzantines (Athènes, 1976), Rapports et corapports I. Athens. pp. 20–21.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Fine 1994, p. 163.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 235.

- ^ Nicol 1984, pp. 38–42.

- ^ Nicol 1984, pp. 83–89.

- ^ Soustal & Koder 1981, p. 167.

- ^ Soustal & Koder 1981, pp. 70, 166.

- ^ Nicol 1984, pp. 123–138.

- ^ Soustal & Koder 1981, pp. 70–71, 166.

- ^ Nicol 1984, pp. 139–143.

- ^ Soustal & Koder 1981, pp. 71, 166.

- ^ Nicol 1984, pp. 143–146.

- ^ Soustal & Koder 1981, pp. 72–73, 166.

- ^ Osswald, Brendan (2007). The Ethnic Composition of Medieval Epirus. S.G.Ellis; L.Klusakova. Imagining frontiers, contesting identities. Pisa University Press. pp. 133–136. ISBN 978-88-8492-466-7.

Carlo Tocco, once he obtained the submission of Albanian clans, had no reason to expel them. His army, from the beginning of his conquests, was composed mainly of Albanians. So was the army of Ioannina before he ruled the city.

- ^ Soustal & Koder 1981, p. 75, 166.

- ^ a b Γεώργιος Ι. Σουλιώτης Γιάννινα (Οδηγός Δημοτικού Μουσείου και Πόλεως 1975

- ^ Π. Αραβαντινού, Βιογραφική Συλλογή Λογίων της Τουρκοκρατίας, Εκδόσεις Ε.Η.Μ., 1960.

- ^ Sakellariou 1997, p. 261.

- ^ a b Sakellariou 1997, p. 268.

- ^ Bruce, Merry (2004). Encyclopedia of modern Greek literature. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-313-30813-0. Archived from the original on 30 September 2023. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

...were destroyed in this vast act of arson by Ali

- ^ S. Mpettis, Enlightenment. Contribution and study of the Epirote enlightment. Epirotiki Estia, 1967, pg. 497–499.

- ^ Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière Hammond. Collected Studies: Alexander and his successors in Macedonia Archived 29 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine. A. M. Hakkert, 1993, p. 404.

- ^ "Ιστορία της πολιορκίας των Ιωαννίνων 1820-1822" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 October 2022. Retrieved 28 October 2022.

- ^ Κώστας Βλάχος Η., "Ζωσιμαία Σχολή Ιωαννίνων" from the archives of the Zosimaia.

- ^ Somel, Selçuk Akşin (2001). The modernization of public education in the Ottoman Empire, 1839–1908: Islamization, autocracy, and discipline. BRILL. p. 209. ISBN 978-90-04-11903-1.

- ^ Skendi, Stavro (1967). The Albanian national awakening, 1878–1912. Princeton University Press. p. 41.

- ^ Trencsényi, Balázs; Kopeček, Michal (2006). Discourses of collective identity in Central and Southeast Europe (1770–1945): texts and commentaries. Late Enlightenment – Emergence of the Modern National Idea. Vol. 1. Central European University Press. p. 348. ISBN 978-963-7326-52-3. Archived from the original on 30 September 2023. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

- ^ Skoulidas, Ilias (2001). The Relations Between the Greeks and the Albanians During the 19th Century: Political Aspirations and Visions (1875-1897). Didaktorika.gr (Doctoral Dissertation). Πανεπιστήμιο Ιωαννίνων. Σχολή Φιλοσοφική. Τμήμα Ιστορίας και Αρχαιολογίας. Τομέας Ιστορίας Νεώτερων χρόνων. p. 92. doi:10.12681/eadd/12856. hdl:10442/hedi/12856. Archived from the original on 15 December 2021. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

δεν μπορούμε να μιλάμε για οργανωμένη Επιτροπή, αλλά, ενδεχομένως, για Τόσκηδες, προσηλωμένους στην αλβανική εθνική ιδέα, που είχαν παρόμοιες σκέψεις και ιδέες για το μέλλον των Αλβανών και όχι μια συγκεκριμένη πολιτική οργάνωση' δεν μπορεί να θεωρηθεί τυχαίο ότι η Επιτροπή δεν εξέδωσε κανένα έγγραφο ή σφραγίδα ή πολιτική απόφαση.

- ^ Sakellariou 1997, p. 293.

- ^ Bartl, Peter (1995). Shqiptarët [Albanians] (in Albanian) (2nd ed.). Tiranë: Botimer IDK (published 2017). p. 124. ISBN 978-99943-982-87.

- ^ "Kotzageorgis Phokion P, "Pour une définition de la culture ottomane : le cas des Tourkoyanniotes", Études Balkaniques-Cahiers Pierre Belon, 2009/1 (n° 16), p. 17-32". Archived from the original on 11 December 2018. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ Nedialkov, Dimitar (2004). The genesis of air power. Pensoft. ISBN 978-954-642-211-8.

Greek aviation saw action in Epirus until the capture of Jannina on 21 February 1913. On that day, Lt Adamidis landed his Maurice Farman on the Town Hall square, to the adulation of an enthusiastic crowd.

- ^ Foss, Arthur (1978). Epirus. Faber. p. 56. "The population exchange between Greece and Turkey which followed removed all those of Turkish origin so that, by 1940, only some twenty Muslim families of Albanian origin were left. In 1973, only eight Muslim remained, living together in an ancient house in the centre of Ioannina. The local authorities, we are told, had refused to allow them to use one of the remaining mosques for worship, their estates remain sequestered and a long battle for what they regard as their rights has so far come to nothing. Although Albanian, they could hope for no sympathy from the present regime in Albania and there was nowhere else for them to go."

- ^ Sakellariou 1997, p. 391.

- ^ Sakellariou 1997, p. 400.

- ^ Sakellariou 1997, p. 418.

- ^ Ellis, Steven G.; Klusáková, Lud'a (2007). Imagining frontiers, contesting identities. Edizioni Plus. p. 148. ISBN 978-88-8492-466-7.

- ^ Liz Elsby; Kathryn Berman. "'For That, It Deserves a Prize' – The Story of a Two-Thousand Year Old Jewish Community in Ioannina, Greece: An Interview with Survivor Artemis Batis Miron". The International School for Holocaust Studies, Yad Vashem. Archived from the original on 24 September 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Rae Dalven, The Jews of Ioannina, Cadmus Press, Philadelphia, 1990; p. 47.

- ^ "The Holocaust in Ioannina", Kehila Kedosha Janina Synagogue and Museum Archived 8 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine retrieved 5 January 2009

- ^ Raptis, Alekos and Tzallas, Thumios, Deportation of Jews of Ioannina, Kehila Kedosha Janina Synagogue and Museum, 28 July 2005 Archived 26 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine URL accessed 5 January 2009

- ^ "Ioannina, Greece". Edwardvictor.com. Archived from the original on 8 November 2006. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ "Greek Government Must Denounce Anti-Semitic Attack on Holocaust Memorial". Archived from the original on 6 January 2014.

- ^ "DESECRATION OF THE JEWISH CEMETERY OF IOANNINA". Kis.gr. Archived from the original on 22 August 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ "Ioannina Greeks to rally against cemetery vandalism". 13 December 2009. Archived from the original on 16 December 2018. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ "Ένας Ρωμανιώτης κέρδισε στα Γιάννενα". 3 June 2019. Archived from the original on 4 June 2019. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ^ "Doctor thought to be 1st Jewish person voted mayor in Greece". Associated Press. 3 June 2019. Archived from the original on 4 April 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ^ "Greek Jewish Communities Congratulate Country's First Jewish mayor, Moses Elisaf". 3 June 2019. Archived from the original on 8 June 2019. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ^ "Population & housing census 2001 (incl. area and average elevation)" (PDF) (in Greek). National Statistical Service of Greece. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2015.

- ^ "ΦΕΚ B 1292/2010, Kallikratis reform municipalities" (in Greek). Government Gazette. Archived from the original on 10 October 2021. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ "Greek National Weather Service". Archived from the original on 2 March 2013. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ "EMY-Εθνική Μετεωρολογική Υπηρεσία". Hnms.gr. Archived from the original on 2 March 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ a b c "Census Results 2022" (PDF). Hellenic Statistical Authority. p. 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ "Population census 1913" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ "Population census 1920" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ "Population census 1928" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ "Population census 1940" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ "Population census 1951" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ "Population census 1961" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ "Population census 1971" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ^ (in Greek and French) "Population – housing census results of April 5, 1981 Archived 8 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine", p. 299 (p. 299 of pdf), from Hellenic Statistical Authority Archived 6 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Archived 8 January 2018. Retrieved 2018-01-08.

- ^ (in Greek) "De facto population of Greece in the census of March 17, 1991 Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine", p. 108 (p. 110 of pdf), from Hellenic Statistical Authority Archived 6 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Archived 20 August 2017. Retrieved 2018-01-08.

- ^ "Census of permanent population, March 18, 2001 Archived 21 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine", p. 170 (p. 172 of pdf), from Hellenic Statistical Authority Archived 6 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Archived 29 July 2017. Retrieved 2018-01-08.

- ^ "Μουσείο Αλή Πασά και επαναστατικής περιόδου". Museumalipasha.gr. Archived from the original on 7 December 2017. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ^ "Υπουργείο Πολιτισμού και Αθλητισμού | Κάστρο Ιωαννίνων". Odysseus.culture.gr. Ministry of Culture and Sport. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ^ "ODYSSEAS – Ministry of Culture and Sports". Odysseus.culture.gr. Ministry of Culture and Sports. Archived from the original on 3 December 2017. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ^ a b c "Υπουργείο Πολιτισμού και Αθλητισμού | Κάστρο Ιωαννίνων". Odysseus.culture.gr. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ^ "Jewish Synagogue | Travel Ioannina". Travelioannina.com. Tourism Department of Ioannina municipality. Archived from the original on 7 December 2017. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ^ "Mosque and Madrassa of Veli Pasha". Travelioannina.com/. Tourism Department of Ioannina municipality. Archived from the original on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ^ "Mosque of Kaloutsiani". Travelioannina.com. Tourism Department of Ioannina municipality. Archived from the original on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ^ "House of Archbishop (Hussein Bey)". Travelioannina.com. Tourism Department of Ioannina municipality. Archived from the original on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ^ "The Clock Tower | Travel Ioannina". Travelioannina.com. Tourism Department of Ioannina municipality. Archived from the original on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ^ "The Building of the VIII Merarchia | Travel Ioannina". Travelioannina.com. Tourism Department of Ioannina municipality. Archived from the original on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ^ "Architecture | Travel Ioannina". Travelioannina.com. Archived from the original on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ^ "Municipal Ethnographic Museum of Ioannina | Travel Ioannina". Travelioannina.com. Archived from the original on 8 December 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ "Υπουργείο Πολιτισμού και Αθλητισμού | Βυζαντινό Μουσείο Ιωαννίνων". Odysseus.culture.gr. Archived from the original on 9 January 2020. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ "The Silversmithing Museum". Piop.gr. Archived from the original on 8 December 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ "Αρχαιολογικό Μουσείο Ιωαννίνων". Amio.gr. Archived from the original on 8 December 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ "Municipal Artworks Gallery of Ioannina | Travel Ioannina". Travelioannina.com. Archived from the original on 8 December 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ Kosmas, Georgios. "ΜΟΥΣΕΙΟ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΗΣ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑΣ – ΚΕΡΙΝΑ ΟΜΟΙΩΜΑΤΑ – ΠΑΥΛΟΣ ΒΡΕΛΛΗΣ". Vrellis.gr. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ "Plásmata II: Ioannina". Archived from the original on 28 June 2023. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ^ "100.000+ Thank you to Ioannina". Archived from the original on 16 July 2023. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ^ "Μόνιμη σχέση με τα Ιωάννινα, σχεδιάζει το Ίδρυμα Ωνάση". 16 June 2023. Archived from the original on 15 July 2023. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ^ Top 500 (401 to 500) – The Times Higher Education World University Rankings 2011–2016 [1] Archived 6 October 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "CWTS Leiden Ranking 2013 – University of Ioannina". Centre for Science and Technology Studies of Leiden University. Archived from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ UniversityRankings.ch (SERI) 2015 – University of Ioannina [2] Archived 30 September 2023 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 3 February 2016.

- ^ "Ranking Web of Universities". Webometrics. Archived from the original on 30 July 2023. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

- ^ Lazaridis, Themis (2010). "Ranking university departments using the mean h-index". Scientometrics. 82 (2). Scientometrics (2010) 82:211–216, Springer: 211–216. doi:10.1007/s11192-009-0048-4. S2CID 10887922.

- ^ "Archived copy". www.statistics.gr. Archived from the original on 22 November 2015. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "University of Ioannina – History". University of Ioannina. Archived from the original on 4 February 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ "Views of Greece". Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- ^ Averbuck, Alexis; Hall, Rebecca; Hardy, Paula; Iatrou, Helen; Koronakis, Vangelis; Maric, Vesna; McNaughtan, Hugh; Ragozin, Leonid; Richmond, Simon (2023). Lonely Planet Greece. Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-83758-185-6.

- ^ "Ioannina is evolving into a science and technology hub". eKathimerini. Archived from the original on 11 June 2023.

- ^ "Greece signs MoU with the Greek-German Chamber for the recovery plan". Proto Thema. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022.

- ^ Nicol 1984, p. 177.

- ^ Kourmantzē-Panagiōtakou, Helenē (2007). Hē Neoellēnikē anagennēsē sta Giannena : apo ton paroiko emporo ston Ath. Psalida kai ton Iō. Vēlara, 17os-arches 19ou aiona (1. ekd. ed.). Athēna: Gutenberg. p. 26. ISBN 9789600111330. Archived from the original on 30 September 2023. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

Ένας άλλος Γιαννιώτης, ο Επιφάνειος Ηγούμενος, το 1647 κληροδοτεί ποσά για την ίδρυση δύο " νεωτεριστικών " Σχολών στα Ιωάννινα και την Αθήνα αντίστοιχα .

- ^ Mavrommatis], Konstantinos Sp. Staikos [kai] Triantaphyllos E. Sklavenitis; [translation David Hardy]; [photograph Socrates (2001). The publishing centres of the Greeks : from the Renaissance to the Neohellenic Enlightenment : catalogue of exhibition. Athens: National Book Centre of Greece. p. 12. ISBN 9789607894304. Archived from the original on 30 September 2023. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

The press owned by Nikolaos Glykys developed into the most productive centre of the Greek diaspora, and was also the longest-lived Greek press. Its founder was born in Ioannina in 1619 and moved to Venice in 1647,

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sakellariou 1997, p. 261:.

- ^ Myrto Georgopoulou-Verra; Zoe Mylona; et al. (1999). Holy Passion, sacred images : the interaction of Byzantine and western art in icon painting. Athens: Archaeological Receipts Fund. p. 104. ISBN 9789602142578. Archived from the original on 30 September 2023. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

... the third most important Greek press in Venice, owned by Demetrios and Panos Theodosiou from Ioannina. It operated from 1755 till 1824

- ^ Sakellariou 1997, p. 260.

- ^ Michaēl Stamatelatos, Phōteinē Vamva-Stamatelatou (2001). Epitomo geōgraphiko lexiko tēs Hellados. Hermes. p. 271. ISBN 9789603201335. Archived from the original on 30 September 2023. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

- ^ Polioudakis, Georgios (2008). Die Übersetzung deutscher Literatur ins Neugriechische vor der Griechischen Revolution von 1821 (1. Aufl. ed.). Frankfurt am Main: Lang, Peter Frankfurt. pp. 69–70. ISBN 9783631582121. Archived from the original on 30 September 2023. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

Dort wurde Christaris... und starb in 1851

- ^ Sakellariou 1997, p. 305.

- ^ Sakellariou 1997, p. 410.

- ^ "Πάπας και Πατριάρχης Αλεξανδρείας και πάσης γης Αιγύπτου Νικόλαος Ε' (Νικόλαος Ευαγγελίδης)". Archived from the original on 13 January 2022. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ Dorsett, Richard (22 March 2003). "Amalia Old Greek Songs in the New Land 1923–1950 (review)". Sing Out. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2011.

- ^ Χατζής Δημήτρης. EKEBI (in Greek). National Book Centre of Greece. Archived from the original on 10 March 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ^ "Πέθανε ο συνθέτης Τάκης Μουσαφίρης". Naftemporiki (in Greek). 11 March 2021. Archived from the original on 6 December 2021. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ "ΕΝΑΡΞΗ ΣΥΝΕΡΓΑΣΙΑΣ ΜΕ ΓΙΩΡΓΟ ΝΤΑΣΙΟ". 24 September 2019. Archived from the original on 24 September 2019. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ "Panepirotan Stadium". www.stadia.gr. Archived from the original on 29 December 2019. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ^ "Ψηφιακό Αρχείο Πρακτικών Συνεδριάσεων Δημοτικού Συμβουλίου και Δημαρχιακής Επιτροπής Ιωαννίνων". Archived from the original on 29 May 2023. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- ^ "Ιωάννινα-Αγία Νάπα: Μια αδελφοποίηση 26 ετών". 18 May 2023. Archived from the original on 29 May 2023. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- ^ "Limassol Twinned Cities". Limassol (Lemesos) Municipality. Archived from the original on 1 April 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- ^ "Ακόμα πιο κοντά το Ισραήλ "Αδελφοί Δήμοι" Γιάννινα και Kiryat Ono". Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- ^ "Από τη Δομπόλη και τη Ζωσιμαία ως τη Νίζνα". 11 March 2022. Archived from the original on 12 March 2022. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ "Ψηφιακό Αρχείο Πρακτικών Συνεδριάσεων Δημοτικού Συμβουλίου και Δημαρχιακής Επιτροπής Ιωαννίνων". Archived from the original on 29 May 2023. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- ^ "Ιωάννινα-Σβέρτε: αδελφοποίηση". 27 October 2022. Archived from the original on 28 October 2022. Retrieved 28 October 2022.

General sources

edit- Anastassiadou, Meropi (2002). "Yanya". In Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E. & Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume XI: W–Z. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 282–283. ISBN 978-90-04-12756-2.

- Dalven, Rae (1990), The Jews of Ioannina, Cadmus Press, ISBN 9780930685034.

- Fine, John V. A. Jr. (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08260-4.

- Gregory, T. E. (1991). "Ioannina". In Kazhdan, Alexander (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. p. 1006. ISBN 0-19-504652-8.

- Nicol, Donald M. (1984). The Despotate of Epiros, 1267–1479: A Contribution to the History of Greece in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-13089-9.

- Papadopoulou, Varvara N., ed. (2014). Μουσεία στο Κάστρο Ιωαννίνων, Παράλληλες Διαδρομές (in Greek). Hellenic Ministry of Culture, 8th Ephorate of Byzantine Antiquities.

- Sakellariou, M. V. (1997). Epirus, 4000 years of Greek history and civilization. Athens: Ekdotike Athenon. ISBN 978-960-213-371-2.

- Soustal, Peter; Koder, Johannes (1981). Tabula Imperii Byzantini, Band 3: Nikopolis und Kephallēnia (in German). Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. ISBN 978-3-7001-0399-8.

External links

editOfficial

edit- Municipality of Ioannina (in Greek)

Travel

edit- Ioannina – The Greek National Tourism Organization

- Ioannina travel guide

Historical

edit- "Here Their Stories Will Be Told..." The Valley of the Communities at Yad Vashem, Ioannina, at Yad Vashem website