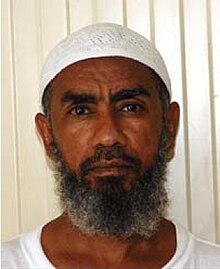

Ibrahim Ahmed Mahmoud al Qosi (Arabic: إبراهيم أحمد محمود القوصي) (born July 1960) is a Sudanese militant and paymaster for al-Qaeda.[3] Qosi was held from January 2002 in extrajudicial detention in the United States Guantanamo Bay detainment camps, in Cuba.[4] His Guantanamo Internment Serial Number is 54.

| Ibrahim Ahmed Mahmoud al Qosi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | July 1960 (age 64)[1][2] Atbara, Sudan |

| Detained at | Guantanamo (2002–2012) |

| Other name(s) | Abu Khubaib al-Sudani |

| ISN | 54 |

| Charge(s) | One of the ten captives to originally face charges before a military commission |

| Status | Guilty plea on July 7, 2010, repatriated to Sudan in 2012, rejoined al-Qaeda in 2014 |

Ibrahim Ahmed Mahmoud al Qosi was held at Guantanamo for approximately ten years and six months; he was charged with low-level support of al-Qaeda.[5] After pleading guilty in a plea bargain in 2010, in the first trial under the military commissions,[6] and serving a short sentence, Qosi was transferred to Sudan by the Obama administration in July 2012. He was to be held in custody and participate in Sudan's re-integration program for former detainees before being allowed to return to his hometown.

Some years after his release, Al Qosi moved to Yemen and joined Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), appearing in video releases by the group and reportedly taking a leadership role in it.[7][8]

In November 2019, the Rewards for Justice Program offered $4 million for information leading to the identification or location of Al Qosi.[9]

Background

editIbrahim Al Qosi was born in 1960 in Atbara, Sudan. He has a brother named Abdullah. He is married to one of Abdullah Tabarak's daughters and has two daughters.[10][11]

In 1990, Qosi was recruited by Sudanese jihadists and later traveled to Afghanistan via the United Arab Emirates and Pakistan, where he trained at a training camp outside of Khost. Two years later, he returned to Khartoum and worked in currency trading. In 1995, he went to Chechnya via Syria, Azerbaijan and Dagestan, where he fought in the First Chechen War as a mortar operator. A year later, he went back to Afghanistan where he aided in the fight against the Northern Alliance from 1998 to 2001. However, he was captured by the Pakistani authorities while trying to cross the Afghan-Pakistani borders on 15 December 2001 near Parachinar, Pakistan. Then he was detained in a prison in Peshawar until 27 December, before being held in US custody at a Kandahar detention facility. Later on, he was transferred to Guantanamo on 13 January 2002.[12]

Qosi was the first captive to face charges before a Guantanamo military commission.[11] He was not accused of being a member of al Qaeda's leadership, only of simple support tasks, like cooking. After pleading guilty in a plea bargain, he was sentenced in July 2010. He was transferred to Sudan in July 2012 after completing a shortened sentence, and was to participate in Sudan's re-integration program for former detainees.

Official status reviews

editOriginally the Bush presidency asserted that captives apprehended in the "war on terror" were not covered by the Geneva Conventions, and could be held indefinitely, without charge, and without an open and transparent review of the justifications for their detention.[13] In 2004, the United States Supreme Court ruled, in Rasul v. Bush, that Guantanamo captives were entitled to being informed of the allegations justifying their detention, and were entitled to try to refute them.

Office for the Administrative Review of Detained Enemy Combatants

editFollowing the Supreme Court's ruling the Department of Defense set up the Office for the Administrative Review of Detained Enemy Combatants.[13] A summary of evidence memo listing allegations justifying his detention was prepared for his Combatant Status Review Tribunal on September 4, 2004.[14]

Scholars at the Brookings Institution, led by Benjamin Wittes, listed the captives still held in Guantanamo in December 2008, according to whether their detention was justified by certain common allegations:[15]

- Ibrahim Ahmed Mahmoud al Qosi was listed as one of the captives who had faced charges before a military commission.[15]

- Ibrahim Ahmed Mahmoud al Qosi was listed as one of the captives who "The military alleges ... are members of Al Qaeda."[15]

- Ibrahim Ahmed Mahmoud al Qosi was listed as one of the captives who "The military alleges ... traveled to Afghanistan for jihad."[15]

- Ibrahim Ahmed Mahmoud al Qosi was listed as one of the captives who "The military alleges ... took military or terrorist training in Afghanistan."[15]

- Ibrahim Ahmed Mahmoud al Qosi was listed as one of the captives who "The military alleges ... fought for the Taliban."[15]

- Ibrahim Ahmed Mahmoud al Qosi was listed as one of the captives who "The military alleges ... were at Tora Bora."[15]

- Ibrahim Ahmed Mahmoud al Qosi was listed as one of the captives who was an "al Qaeda operative".[15]

- Ibrahim Ahmed Mahmoud al Qosi was listed as one of the captives "who have been charged before military commissions and are alleged Al Qaeda operatives."[15]

- Ibrahim Ahmed Mahmoud al Qosi was listed as one of the "82 detainees [who] made no statement to CSRT or ARB tribunals or made statements that do not bear materially on the military's allegations against them."[15]

Habeas petition

editA petition of habeas corpus was filed on Al Qosi's behalf.[16] Following the United States Supreme Court's ruling in Rasul v. Bush (2004) that detainees had the right under habeas corpus to an impartial tribunal to challenge their detention, more than 200 captives had habeas corpus petitions filed on their behalf. Congress passed the Detainee Treatment Act of 2005 (DTA) and the Military Commissions Act of 2006 (MCA) at the request of the Bush administration, which suspend their access to the US civilian justice system and shift all responsibility to military tribunals.

In September 2007, the Department of Defense published the unclassified dossiers arising from the Combatant Status Review Tribunals of 179 captives.[17] The Department of Defense withheld the unclassified documents from Al Qosi's tribunal without explanation.

On June 12, 2008, in its landmark ruling in the Boumediene v. Bush habeas corpus petition, the United States Supreme Court determined that the MCA was unconstitutional for attempting to deprive the captives' of their constitutional right to habeas corpus. It ruled that detainees could access the US federal courts directly.

Formerly secret Joint Task Force Guantanamo assessment

editOn April 25, 2011, whistleblower organization WikiLeaks published formerly secret assessments drafted by Joint Task Force Guantanamo analysts.[18][19] Al-Qosi's assessment was eleven pages long, and was drafted on November 15, 2007.[20] It was signed by camp commandant Mark H. Buzby. The report noted that al-Qosi had been "compliant and non-hostile to the guard force and staff."

Charged before military commissions

editOn February 24, 2004, al Qosi was named in documents for the first military commissions to be held for detainees.[21] The United States alleged that he joined al-Qaeda in 1989 and worked as a driver and bodyguard for Osama bin Laden, as well as working as a quartermaster for al-Qaeda. He was also alleged to have been the treasurer of a business which was an al-Qaida front.

He was indicted along with Ali Hamza Ahmed Sulayman al Bahlul. The indictment allowed the detainees to consult with military defense lawyers assigned by the government to prepare their defenses. Al Qosi was charged with conspiracy to commit war crimes, including attacking civilians, murder, destruction of property, and terrorism.

Lieutenant Colonel Sharon Shaffer USAF (Judge Advocates Group) was appointed al Qosi's defense lawyer on February 6, 2004.[22]

On August 27, 2004, Shaffer complained that the prosecution was not providing her with the information she needed for her defense of al Qosi. She said that al Qosi had informed her that the quality of translation at his military commission was insufficient for him to understand what was happening.[23] She told the tribunal that she had to resign as al Qosi's attorney.

According to the Voice of America, Chief Prosecutor Colonel Robert L. Swann assured the commission that: "...all resources will be devoted to obtaining the most accurate translations possible."[23]

On November 9, 2004, legal action against Qosi was suspended,[24] The US District Court Justice James Robertson had ruled, in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, that the military commissions violated international agreements to which the United States was a signatory, including part of the Geneva Conventions. This ruling applied to all four of the detainees who had been charged by the military commission.

In 2005, a three-judge appeals panel overturned Robertson's ruling, setting the commissions back in motion. In Hamdan v. Rumsfeld (2006), the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the president lacked the constitutional authority to establish military the military commissions, and that only Congress could do so. Congress subsequently passed the Military Commissions Act of 2006, which included provisions to suspend the access of detainees to habeas corpus in the US courts.

On February 9, 2008, al Qosi and Ali Hamza Suleiman Al Bahlul were charged before the congressionally authorized Guantanamo military commissions authorized by the Military Commissions Act of 2006.[25][26]

Phoning home

editIbrahim al Qosi was among those who was granted access to telephone privileges.

On May 22, 2008, Lieutenant Colonel Nancy Paul, the presiding officer of his commission ordered that Ibrahim al Qosi be permitted his first phone call home.[27][28] While it was reported that the phone call was made, this was in error. Qosi had declined to leave his cell to meet with Commander Suzanne Lachelier, his assigned legal counsel, and the Camp's security rules do not permit her going to his cell to talk to him—so they have never discussed his case. During a preliminary hearing, Ibrahim Al Qosi told Paul he does not want to be represented by an American lawyer. He said that he had been unable to hire the lawyer of his choice because he had been isolated in Guantanamo, and had been unable to contact his family since his detention.

Later that day, Commander Pauline Storum, a Guantanamo spokesman, reported that the call had been completed, and that he had spoken with his family for an hour.[27][29][30]

On May 23, 2008, Storum sent an apology by e-mail to reporters to retract her claim the phone call had been completed.[29][30]

I misspoke when I confirmed that al Qosi's call was complete. In clarifying the current status of the detainee phone program, I misunderstood the information I was given, and inaccurately conveyed that al Qosi's call was completed.

I apologize for the error.

Ibrahim al-Qosi's appointed counsel, Suzanne Lachelier, told Carol Rosenberg, of the Miami Herald, that she was surprised to learn, through press reports, that the call had been completed.[29] She said she had only begun to initiate the co-ordination with the Red Cross to arrange for his family to be set up to receive the call when she learned the call had already been completed. According to Rosenberg:

The original statement Thursday struck some observers as extraordinary -- for both its speed and the coordination between the separate bureaucracies of the prison camp and the war court.

The Department of Defense had until July 1, 2008, to arrange the phone call.[30]

The US Supreme Court ruled in Boumediene v. Bush (2008) that the Military Commissions Act of 2006 was unconstitutional, as it suspended the right of habeas corpus of detainees. Military commissions were suspended.

July 2009 hearing

editOn July 15, 2009, al Qosi had his first hearing that year.[31] According to Carol Rosenberg, writing in the Lakeland Ledger, the electronic audio management equipment the court had been supplied with in 2008 initially failed to function properly. Rosenberg reported that al Qosi's defense team was concerned that the prosecution was imposing improper delays, and noted they had told the presiding officer.

Continuance

editThe Barack Obama presidency was granted a continuance on October 21, 2009.[32] Congress had amended the MCA, passing the Military Commissions Act of 2009, and the Department of Defense needed to create regulations to implement it. The military commissions for five other captives were granted continuances, until November 16, 2009. Ibrahim al Qosi did not attend this hearing.

New charges rejected, status determination scheduled

editOn December 3, 2009, Paul ruled that the charges against Al Qosi should be limited to crimes he was alleged to have committed in Afghanistan.[33][34] She ruled that crimes he was alleged to have committed when al Qaeda was based in Sudan were beyond the mandate of the military commission system.

Carol Rosenberg, writing in the Miami Herald, reported that Paul scheduled hearings for January 6, 2010, to determine whether Al Qosi met the eligibility criteria as an illegal enemy combatant as laid out in the Military Commissions Act of 2006. Only if he was classified under that status would the military commission have jurisdiction to try him.[35][36] Rosenberg described Paul as the first presiding officer of a military commission to address the changes that US Congress set in place when passing the Military Commissions Act of 2009.

Andrea Prasow, a senior counsel with Human Rights Watch, was critical of Paul for proceeding with the commission, although the government had not completed drafting the rules of procedure under the act.[37]

Guilty Plea

editOn July 7, 2010, al Qosi entered a guilty plea under a plea bargain deal, the details of which have not been publicly released. His sentencing was set for August 9, 2010.[6][38] On August 11, 2010, a military jury at Guantanamo recommended that al-Qosi serve 14 years in prison.[39]

Appeal dismissed

editOther individuals who, like al-Qosi, had pleaded guilty to "providing material support for terrorism", had their convictions overturned on appeal.[40] Appeals courts ruled that the charge was not a crime at the time the acts were committed. In 2014, Al-Qosi's military-appointed lawyer, Mary McCormick, attempted to have al-Qosi's conviction overturned, following the precedent of the over-turning the convictions of other men convicted of the same charge. The United States Court of Military Commission Review first declined to provide funds for McCormick to travel to Sudan to consult with al-Qosi, and then ruled that she could not prove she had an attorney–client relationship, on his behalf. Finally, the USCMCR ruled that since McCormick could not prove she had an attorney–client relationship she was not authorized to file motions on al-Qosi's behalf. On May 1, 2015, three judges of the DC Circuit Court of Appeals confirmed that McCormick could not prove she had an attorney–client relationship.

Steve Vladeck, a professor of law who specializes in security matters, described the decision by the USCMCR to withhold funds from McCormick so she could renew contact with al-Qosi because she could not document that she remained in contact with him as "somewhat circular".[40]

Repatriation

editWhen al Qosi was transferred to Sudan by the Obama administration on July 11, 2012, his lawyer Paul Reichler said al Qosi will enter a Sudan government "re-integration program:"[11]

One of the main reasons the United States was willing to return him to Sudan was the U.S. confidence in the government of Sudan's program and its confidence that Mr. al-Qosi would not represent any kind of threat to the United States. If they had considered him a threat, they would not have released him."[11]

al Qosi was held in Sudan's capital, Khartoum, during the initial period of his re-integration. He was eventually transferred to his home town of Afbara.[11] Nine other former Guantanamo detainees went through the reintegration program with no sign of recidivism.

Recidivism

editIn December 2015, al Qosi (as Sheikh Khubayb al Sudani) was featured in a video released by al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, which he reportedly joined in 2014. The footage showed him and other al-Qaeda veterans encouraging "individual jihad".[7]

He gave a 12-page interview on the life and legacy of Osama bin Laden in the AQAP magazine "Inspire" Spring 2016 issue (#15).[41]

In October 2021, Qosi threatened the United States with attacks and praised Nidal Hasan.[42]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Archived copy Archived 2022-01-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Ibrahim Ahmed Mahmoud al-Qosi – Rewards For Justice". Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ On Trial At Gitmo: Ibrahim Ahmed Mahmoud al Qosi Archived 2009-02-18 at the Wayback Machine, CBS News, August 24, 2004

- ^ "List of Individuals Detained by the Department of Defense at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba from January 2002 through May 15, 2006" (PDF). United States Department of Defense. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2006-05-15. Works related to List of Individuals Detained by the Department of Defense at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba from January 2002 through May 15, 2006 at Wikisource

- ^ Margot Williams (2008-11-03). "Guantanamo Docket: Ibrahim Ahmed Mahmoud al Qosi". New York Times. Archived from the original on 2017-02-04. Retrieved 2012-07-11.

- ^ a b "Al-Qosi Plea Is First Conviction In Broken Military Commissions Under Obama". ACLU. 2010-07-07. Archived from the original on 2015-03-14. Retrieved 2016-12-04.

- ^ a b Joscelyn, Thomas. "Ex-Guantanamo detainee now an al Qaeda leader in Yemen". Long War Journal. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- ^ "Freed Guantanamo detainees: Where are they now?". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 10 January 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- ^ "Wanted: Ibrahim Ahmed Mahmoud al-Qosi". Rewards for Justice. Archived from the original on 23 November 2019. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- ^ "Convicted al Qaida operative released from Guantánamo, repatriated to Sudan in plea deal - Guantánamo - MiamiHerald.com". Miami Herald. Archived from the original on 2012-07-11.

- ^ a b c d e

"Guantanamo prisoner returns home to Sudan after 10 years in custody". Washington Post. 2012-07-11. Archived from the original on July 12, 2012. Retrieved 2012-07-11.

A man who spent a decade as a prisoner in the U.S. detention facility for militants in Guantanamo Bay returned Wednesday to his native Sudan after completing a shortened sentence for aiding al-Qaida in Afghanistan.

- ^ "The Guantanamo Docket: Ibrahim Ahmed Mahmoud al Qosi". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 February 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- ^ a b

"U.S. military reviews 'enemy combatant' use". USA Today. 2007-10-11. Archived from the original on 2007-10-23.

Critics called it an overdue acknowledgment that the so-called Combatant Status Review Tribunals are unfairly geared toward labeling detainees the enemy, even when they pose little danger. Simply redoing the tribunals won't fix the problem, they said, because the system still allows coerced evidence and denies detainees legal representation.

- ^ OARDEC (2004-09-04). "Summary of Evidence for Combatant Status Review Tribunal -- Al Qosi, Ibrahim Ahmed Mahmoud" (PDF). United States Department of Defense. pp. 65–66. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-12-02. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Benjamin Wittes, Zaathira Wyne (2008-12-16). "The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: An Empirical Study" (PDF). The Brookings Institution. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-06-01. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- ^ Joyce Hens Green. "In re Guantanamo Detainee Cases -- Joyce Hens Green". United States Department of Justice. Archived from the original on 2007-10-05. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

- ^ OARDEC (August 8, 2007). "Index for CSRT Records Publicly Files in Guantanamo Detainee Cases" (PDF). United States Department of Defense. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2007-10-26. Retrieved 2007-09-29.

- ^

Christopher Hope; Robert Winnett; Holly Watt; Heidi Blake (2011-04-27). "WikiLeaks: Guantanamo Bay terrorist secrets revealed -- Guantanamo Bay has been used to incarcerate dozens of terrorists who have admitted plotting terrifying attacks against the West – while imprisoning more than 150 totally innocent people, top-secret files disclose". The Telegraph (UK). Archived from the original on 2012-07-15. Retrieved 2012-07-13.

The Daily Telegraph, along with other newspapers including The Washington Post, today exposes America's own analysis of almost ten years of controversial interrogations on the world's most dangerous terrorists. This newspaper has been shown thousands of pages of top-secret files obtained by the WikiLeaks website.

- ^ "WikiLeaks: The Guantánamo files database". The Telegraph (UK). 2011-04-27. Archived from the original on April 29, 2011. Retrieved 2012-07-10.

- ^ "Ibrahim Ahmed Mahmoud Al Qosi: Guantanamo Bay detainee file on Ibrahim Ahmed Mahmoud Al Qosi, US9SU-000054DP, passed to the Telegraph by Wikileaks". The Telegraph (UK). 2011-04-27. Archived from the original on 2015-04-11. Retrieved 2015-05-05.

Recommendation: Continued detention under DoD control

- ^ "2 Gitmo Prisoners To Stand Trial", CBS News, February 24, 2004

- ^ Two Guantanamo Detainees Assigned Legal Counsel Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine, US State Department, February 6, 2004

- ^ a b "Week of Hearings for Accused Terrorists Wraps Up in Guantanamo" Archived 2006-01-07 at the Wayback Machine, Voice of America, August 27, 2004

- ^ Guantánamo: Military commissions - Amnesty International observer’s notes, No. 3 -- Proceedings suspended following order by US federal judge Archived 2018-11-22 at the Wayback Machine, Amnesty International, November 9, 2004

- ^ Jane Sutton (February 9, 2008). "US military charges two more Guantanamo captives". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2008-03-06. Retrieved 2008-02-09.

- ^ J. Treanor (February 8, 2008). "Charge Sheet: Ibrahim Ahmed Mahmoud Al Qosi" (PDF). Office of Military Commissions. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 26, 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- ^ a b

Carol Rosenberg (May 22, 2008). "Terror suspect phones Sudan to hire own lawyer". Miami Herald. Archived from the original on May 24, 2024. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

Within hours of a judge's order, an accused al Qaeda conspirator from Sudan got a call from home Thursday to consult with his family on how they might hire him a lawyer, at their own expense.

- ^ "Guantanamo judge orders military to allow detainee phone call home to Sudan". International Herald Tribune. May 22, 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- ^ a b c

Carol Rosenberg (May 24, 2008). "Guantánamo: Detainee didn't get call from home". Miami Herald. Archived from the original on May 24, 2024. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

A military spokesman "erred last week" by telling journalists that an alleged al Qaeda conspirator at Guantánamo received a Red Cross-assisted telephone call from home.

- ^ a b c Jane Sutton (May 24, 2008). "Guantanamo phone report was in error, U.S. says". Reuters. Archived from the original on February 17, 2012. Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- ^ a b

Carol Rosenberg (2009-07-15). "Pentagon Presses Ahead With War Court". The Ledger. p. A10. Archived from the original on 2011-06-14. Retrieved 2009-07-28.

The Sudanese captive's military lawyers struck a contrarian's note by arguing for a speedy trial in the case, invoking a "justice-delayed, justice-denied" argument on the grounds Qosi was among the first men taken to the prison camps when they opened in January 2002. President Barack Obama has ordered the prison camps emptied by Jan. 22.

- ^ "Delays granted in 2 Guantanamo war crimes cases". Associated Press. 2009-10-21. Archived from the original on 2024-05-24.

- ^ "Judge limits case against alleged bin Laden bodyguard to Afghanistan crimes". Dallas Morning News. 2009-12-04. Archived from the original on 2011-06-04.

- ^ Nancy Paul (2009-12-03). "United States of America v. Ihrahm Ahmed Mohmoud al Qosi -- Ruling: P-010 Government motion to amend charges" (PDF). Office of Military Commissions. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-02.

- ^ Carol Rosenberg (2009-12-03). "Guantánamo judge won't expand Sudanese captive's war crimes case". Miami Herald. Archived from the original on 2024-05-24.

- ^ Nancy Paul (2009-12-03). "United States of America v. Ihrahm Ahmed Mohmoud al Qosi -- Ruling: D-023 Defense motion for article 5 status determination, or, alternatively, dismissal for lack of personal Jurisdiction" (PDF). Office of Military Commissions. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-27.

- ^ Andrea Prasow (2009-12-08). "Falling Short: Justice in the New Military Commissions". The Jurist. Archived from the original on 2009-12-14.

- ^ Reuters (2010-07-08). "Guantanamo detainee Ibrahim Ahmed Mahmoud al Qosi pleads guilty". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2017-11-04. Retrieved 2017-09-01.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "Military jury recommends a 14-year sentence for bin Laden's driver". CNN. 2010-08-12. Archived from the original on 2012-11-08. Retrieved 2010-08-12.

- ^ a b Steve Vladeck (2015-05-01). "The Government (Sort of) Wins a Guantánamo Military Commission Appeal". Just Security. Archived from the original on 2015-05-05. Retrieved 2015-05-04.

- ^ "Inspire Magazine, issue #15" (PDF). Jihadology.net. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 August 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ "Senior Official Of Al-Qaeda In The Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) Ibrahim Al-Qousi Threatens U.S. With Attacks More Painful, Powerful Than 9/11". Archived from the original on 2021-10-10. Retrieved 2021-10-10.

External links

edit- "Bin Laden’s cook is moved to isolation in Gitmo", Al Arabiya, 10 October 2010

- "Military Commissions", Human Rights First blog

- Human Rights First; The Case of Ibrahim Ahmed Mahmoud al Qosi, Sudan, Human Rights First

- "Former bin Laden cook reaches secret sentencing deal with U.S. government", Washington Post, 9 August 2010

- "Bin Laden Cook Accepts Plea Deal at Guantánamo Trial" Andy Worthington, 8 July 2010

- "Sentencing of detainee stalls at Guantanamo", Washington Post, August 2010