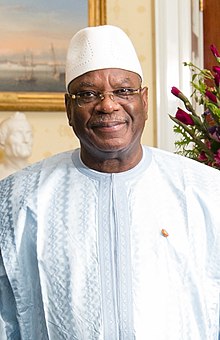

Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta (French: [ibʁa.im bubakaʁ ke.ita]; 29 January 1945 – 16 January 2022), often known by his initials IBK, was a Malian politician who served as the president of Mali from September 2013 to August 2020, when he was forced to resign in the 2020 Malian coup d'état. He served as Mali's prime minister from February 1994 to February 2000 and as president of the National Assembly of Mali from September 2002[1][2] to September 2007.[3]

Keïta founded the centre-left political party Rally for Mali (RPM) in 2001.[4] After a number of unsuccessful campaigns, he was elected president in the 2013 presidential election and reelected in 2018. He was deposed by mutinous elements of the Malian Armed Forces on 18 August 2020 and officially resigned the following day.[5]

Early life and education

editKeïta was born in Koutiala, in what was then French Sudan.[1][2] His great-grandfather reportedly fought on the French side during World War I and was killed at the Battle of Verdun.[6] He is a relative of Mali's founding father Modibo Keïta and he is a descendant of the Keita princes of the Empire of Mali. Keïta studied at the Lycée Janson-de-Sailly in Paris and Lycée Askia-Mohamed in Bamako, continuing his education at the University of Dakar, the University of Paris I and the Institut d'Histoire des Relations Internationales Contemporaines (IHRIC; Institute of the Modern History of International Relations).[7][8] He graduated with a master's degree in history and postgraduate degrees in political science and international relations.[9]

After his studies, he was a researcher at the CNRS and taught Third World politics at the University of Paris I.[10] Returning to Mali in 1986, he became a technical consultant for the European Development Fund, putting together the first small-scale development program for the European Union's aid activities in Mali.[8] He went on to become Mali director for the French chapter of Terre des hommes, an international NGO aiding children in the developing world.[10]

Early political career

editUpon the founding of the Alliance for Democracy in Mali (ADEMA-PASJ), Keïta became its Secretary for African and International Relations at its constitutive congress, held on 25–26 May 1991.[11] He was the deputy director of ADEMA candidate Alpha Oumar Konaré's successful presidential campaign in 1992. The new president named Keïta as his senior diplomatic adviser and spokesman in June 1992, and then in November 1992 Konaré appointed Keïta as Ambassador to Côte d'Ivoire, Gabon, Burkina Faso and Niger.[1][2]

In November 1993, Keïta was appointed to the Malian government as Minister of External Affairs, Malians Abroad, and African Integration. On 4 February 1994, President Konaré named him prime minister, a position he held until February 2000.[1][2] At ADEMA's first ordinary congress, held in September 1994, Keïta was elected as the president of ADEMA.[12] Following presidential and parliamentary elections held in 1997, he resigned from his post as prime minister on 13 September 1997[13] and was promptly reappointed by Konaré, with a new government appointed on 16 September.[14] Keïta was re-elected as ADEMA president in October 1999,[15] and in November 1999, he was named vice-president of the Socialist International.[1]

Disagreements within ADEMA forced him to resign as prime minister on 14 February 2000, and then from the leadership of the party in October 2000. He then founded his own party, the Rally for Mali (RPM), which he has led since its creation was announced on 30 June 2001.[1][16] He stood as a candidate in the 2002 presidential election, receiving the strong backing of many Muslim leaders and associations. Despite this support, some people doubted that Keïta's policies were particularly compatible with Islam, pointing to the creation of casinos and lotteries while he was Prime Minister.[17] In the first round of the election, held on 28 April, he received about 21% of the vote and took third place, behind Amadou Toumani Touré and Soumaïla Cissé.[18] He denounced the election as fraudulent, alleging that he was deliberately and falsely excluded from the second round, and along with other candidates sought the invalidation of results.[19][20] On 9 May the Constitutional Court ruled that the second round should proceed with Touré and Cissé as the top two candidates, despite acknowledging significant irregularities and disqualifying a quarter of the votes because of the irregularities.[21][22] According to the Constitutional Court, Keïta won 21.03% of the vote, only about 4,000 votes less than Cissé.[18][22] On the same day, Keïta announced the support of his Espoir 2002 alliance for Touré in the second round;[21][22] regarding the Court's ruling, he described himself as "a law-abiding person" and said that the Court had followed the law.[22] The second round was won by Touré.[23]

In the July 2002 parliamentary election, Keïta was elected to a seat in the National Assembly from Commune IV in Bamako District[1][2][24] in the first round.[2][24] He was then elected as President of the National Assembly on 16 September 2002,[1][23][25][26] receiving broad support, including the backing of ADEMA.[25] He received 115 votes from the 138 participating deputies;[25][26] the only other candidate, Noumoutié Sogoba of African Solidarity for Democracy and Independence (SADI), received eight votes, while 15 deputies abstained.[25]

Keïta was also elected as President of the Executive Committee of the African Parliamentary Union on 24 October 2002 at its Khartoum Conference.[1]

He ran for president again, as the candidate of the Rally for Mali, in the April 2007 election, having been designated as the party's candidate on 28 January 2007.[27] Touré won the election by a landslide, while Keita took second place and 19.15% of the vote.[28] As part of the Front for Democracy and the Republic (FDR), a coalition that included Keita as well as three other presidential candidates, Keita disputed the results and sought the annulment of the election, alleging fraud.[29] On 19 May, he said that the FDR would abide by the decision of the Constitutional Court to confirm Touré's victory.[30]

In the July 2007 parliamentary election, Keïta ran for re-election to the National Assembly from Commune IV in Bamako, where 17 lists competed for the two available seats,[31] on an RPM list together with Abdramane Sylla.[32] Keïta's list received 31.52% of the vote in the first round, held on 1 July,[24][32] slightly ahead of the list of independent candidate Moussa Mara, which received 30.70%.[32] In the second round on 22 July, Keïta's list narrowly prevailed, winning 51.59% of the vote according to provisional results.[33] He was not a candidate for re-election as President of the National Assembly at the opening of the new National Assembly on 3 September; the position was won by ADEMA President Dioncounda Traoré.[3][34]

Keïta was a member of the Pan-African Parliament from Mali.[35] As of 2007–2008, he was a member of the Commission of Foreign Affairs, Malians Living Abroad, and African Integration in the National Assembly.[36] In addition to serving in the National Assembly, Keïta was a member of the Parliament of the Economic Community of West African States.[37]

President of Mali

editKeïta again ran for president in the July–August 2013 presidential election and was considered a front-runner.[38][39] He won the election in a second round of voting, defeating Soumaïla Cissé, and was sworn in by the Supreme Court of Mali as president on 4 September 2013.[40]

Keïta had vowed to prioritize ability rather than political considerations when appointing ministers, and on 5 September 2013 he appointed a technocrat, banking official Oumar Tatam Ly, as prime minister.[41] After Oumar Tatam Ly's resignation, Keïta appointed Moussa Mara (5 April 2014 to 9 January 2015) and Modibo Keita (9 January 2015 to 7 April 2017). Upon Keita's resignation, Soumeylou Boubéye Maïga was appointed prime minister (31 December 2017 – 18 April 2019) but resigned on 18 April 2019 amid public protests following the Ogossagou massacre.[42] Keita named Boubou Cissé as Maïga's replacement on 22 April.[43]

Throughout his presidency, Keïta worked tirelessly to strengthen democracy and seek peace with the rebels and bring stability in Mali as the Mali War continued onward. He was unwavering in his determination for national dialogue and reconciliation with parties across the country whilst leading efforts against insurgents and terrorists during his presidency. Another challenge during his tenure in office was the infrastructure since income was low is undiversified and vulnerable to commodity fluctuations. As the president of Mali poverty would decrease from 94% to 80.50% when his presidency ended in the 2020 Malian coup d'état. The cause for this was a 50 million dollar agreement with the World Bank to protect poor Malians and to boost the Country’s recovery from crisis. The agreement with the world bank will support emergency recovery programs in the country’s Sustainable Recovery Plan, including strengthening social safety net protection for poor and vulnerable families, deepening controls on budget and transparency, and restoring financial sustainability and investment capacity in the power and water irrigation sectors. These activities are part of a broader policy reform agenda being carried out by the Mali Government.

When taking office in 2013 the MLNA had ended ceasefire after government forces opened fire on unarmed protesters. Following the attack the MLNA launched an attack on the Malian government. Another ceasefire was agreed upon on 20 February 2015 between the Malian government and the northern rebels. In March 2020, Malian authorities recorded the country's first coronavirus infections, in two nationals who had recently arrived from France. Experts fear the country is particularly exposed to an outbreak because of its jihadist conflict, which first broke out in the north in 2012 and has since engulfed the centre. Thousands of soldiers and civilians have died in the Mali war. On 18 March, President Keita suspended flights from affected countries, closed schools and banned large public gatherings. However planned elections in March–April, which had already been postponed several times for the poor security situation in the country, went ahead as planned.

2020 coup

editAn opposition movement coalesced against Keïta's presidency and its acquiescence to the presence of French troops in the country. This movement gained international visibility through mass demonstrations organized by the June 5 Movement – Rally of Patriotic Forces (M5-RFP), continuing throughout 2020 despite the coronavirus pandemic and police repression.[44] On 18 August 2020, Keïta and Cissé were arrested by mutinying soldiers in a coup d'état.[45] The next day, Keïta dissolved parliament and announced his resignation, saying he wanted "no blood to be spilled" to keep him in power.[46][47] He was released from custody on 27 August according to a junta spokesman.[48]

Personal life and death

editKeïta was married to Keïta Aminata Maiga, who was the First Lady of Mali while Keïta was in office as President, and had four children.[49] His son Karim is a member of the National Assembly and married to a daughter of Issaka Sidibé, President of the National Assembly.[50]

He died in his home in Bamako on 16 January 2022, thirteen days before his 77th birthday.[51]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i National Assembly page for Keïta Archived 9 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b c d e f Candidate profile[usurped], Bamanet.net, 20 April 2007 (in French).

- ^ a b "L'EFFET "IBK"" Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, L'Essor, number 16,026, 4 September 2007 (in French).

- ^ National Political Bureau of the RPM[permanent dead link] (in French).

- ^ "Mali's Keita resigns as president after military coup". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ Van Eyssen, Benita (11 November 2018). "The 'Black Army' that marched in from Africa". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- ^ Heath-Brown, Nick (7 February 2017). The Statesman's Yearbook 2016: The Politics, Cultures and Economies of the World. Springer. p. 809. ISBN 978-1-349-57823-8.

- ^ a b "Profile: Ibrahim Boubacar Keita, Mali's overthrown president". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ "Mali's ex-President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita dies at 76". Associated Press. 16 January 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ a b "Political Trajectory of Mali's Ex-President IBK". Africanews. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ "Membres du conseil exécutif de l'Adéma-PASJ élus au congrès constitutif du 25 et 26 Mai 1991.", ADEMA website (in French).

- ^ "Membres du conseil exécutif de l'Adéma-PASJ élus au premier congrès ordinaire de Septembre 1994.", ADEMA website (in French).

- ^ "Mali: Prime Minister Keita resigns", Radio France Internationale (nl.newsbank.com), 14 September 1997.

- ^ "Mali: President Konare forms new cabinet", RTM radio, Bamako (nl.newsbank.com), 17 September 1997.

- ^ "DIRECTION NATIONALE: Comité exécutif 1999 - 2000", ADEMA website (in French).

- ^ "L'ancien Premier ministre, Ibrahim Boubacar Keita, crée son parti" Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Afrique Express, number 231, 2 July 2001 (in French).

- ^ "Mali's Muslim leaders back ex-premier", BBC News, 26 April 2002.

- ^ a b "1er tour de l'élection présidentielle au Mali : Verdict de la Cour Constitutionnelle"[permanent dead link], L'Essor, 9 May 2002 (in French).

- ^ Joan Baxter, "Mali court reviews 'vote-rigging'", BBC News, 7 May 2002.

- ^ "MALI: Malians await court's decision", IRIN, 7 May 2002.

- ^ a b "Mali: Constitutional Court affirms second round", IRIN, 10 May 2002.

- ^ a b c d "Mali's opposition backs general", BBC News, 10 May 2002.

- ^ a b 2002 timeline Archived 4 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine on the official site of the Malian presidency.

- ^ a b c "Législatives au Mali: la mouvance présidentielle en tête au 1er tour" Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, AFP (Jeuneafrique.com), 6 July 2007 (in French).

- ^ a b c d Francis Kpatindé, "Retour triomphal pour Ibrahim Boubacar Keita"[permanent dead link], Jeune Afrique, 7 October 2002 (in French).

- ^ a b "Démission du gouvernement, Ahmed Mohamed Ag Hamani reconduit au poste de premier ministre" Archived 10 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Afrique Express, number 257, 17 October 2002 (in French).

- ^ "IBK investi par son parti candidat à l’élection présidentielle prochaine au Mali" Archived 5 August 2007 at archive.today, African Press Agency, 28 January 2007 (in French).

- ^ "Présidentielle au Mali: la Cour constitutionnelle valide la réélection de Touré" Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, AFP, 12 May 2007 (in French).

- ^ "Mali: l'opposition conteste la présidentielle sans attendre les résultats" Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, AFP, 1 May 2007 (in French).

- ^ "Mali opposition concedes Toure's re-election", Reuters, 21 May 2007.

- ^ B. S. Diarra, "Faut-il abattre IBK ?" Archived 20 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Aurore, 18 June 2007 (in French).

- ^ a b c "Commune IV : DUEL SINGULIER" Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, L'Essor, 19 July 2007 (in French).

- ^ M. Kéita, "2è tour des législatives à Bamako : AVANTAGE À L'ADEMA ET AU CNID" Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, L'Essor, number 15,996, 24 July 2007 (in French).

- ^ "Mali: Dioncounda Traoré élu président de l'Assemblée nationale" Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, AFP, 3 September 2007 (in French).

- ^ List of members of the Pan-African Parliament Archived 12 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Liste des députés membres de la commission Affaires Etrangères-Maliens de l'extérieur et Intégration Africaine" Archived 31 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine, National Assembly website (in French).

- ^ "Liste des députés Membres du Parlement de la CEDEAO" Archived 23 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, National Assembly website (in French).

- ^ R., A. (29 July 2013). "A relatively calm affair". The Economist. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- ^ "Voters defy threats as polls close in Mali". Al-Jazeera. 28 July 2013. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- ^ Tiemoko Diallo and Adama Diarra, "Mali's new president promises to bring peace, fight graft", Reuters, 4 September 2013.

- ^ "New Mali president names banker as first prime minister", Reuters, 6 September 2013.

- ^ Sahelien.com (30 December 2017). "Mali: Soumeylou Boubeye Maïga appointed Prime Minister | sahelien.com | English". Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ^ "Mali names new prime minister after ethnic massacre". Deutsche Welle. 22 April 2019. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ Thurston, Alex (18 August 2020). "An Apparent Military Coup in Mali: 10 Questions". Sahel Blog. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

The coup comes amid a summer of protests by the "June 5 Movement – Rally of Patriotic Forces" (French acronym M5-RFP), a Bamako-centric coalition of opposition politicians, civil society actors, and the prominent Imam Mahmoud Dicko. The M5-RFP's core demand has (had?) been for President Keïta to resign. This week, the M5-RFP had planned and begun to carry out a series of protest actions, to culminate in another mass protest on Friday. Today, images and videos circulated showing civilian protesters congregating in Bamako's Place de l'Indépendance, the locale for previous M5-RFP protests. Further images and videos showed the protesters welcoming and supporting the mutineers

- ^ Kelly, Jeremy (18 August 2020). "Mali PM and president under arrest, claim army mutineers". The Times. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ "Mali's Keita resigns after military mutiny". Archived from the original on 31 October 2020. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ Mali’s president announces resignation on state television

- ^ Diallo, Tiemoko; (writing) Prentice, Alessandra; (ed.) Chopra, Toby (27 August 2020). "Ousted Mali president Keita has been freed by coup leaders, says junta spokesman". Reuters. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

{{cite news}}:|last3=has generic name (help) - ^ Issouf Sanogo (13 August 2013). "Ibrahim Boubacar Keita, the man to unify troubled Mali". Africa Review. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- ^ "Ally of Mali's President Keita elected parliament speaker". Reuters. 22 January 2014. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- ^ Mali's ousted president Ibrahim Boubacar Keita dies, former minister says