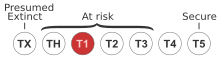

The Mission blue (Icaricia icarioides missionensis)[1] is a blue or lycaenid butterfly subspecies native to the San Francisco Bay Area of the United States. The butterfly has been declared as endangered by the US federal government.[2] It is a subspecies of Boisduval's blue (Icaricia icarioides).

| Mission blue butterfly | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Lepidoptera |

| Family: | Lycaenidae |

| Genus: | Icaricia |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | I. i. missionensis

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Icaricia icarioides missionensis (Hovanitz, 1937)

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Description

editIn the male Mission blue, the dorsal surface of the wings gradate from ice blue in the center to deep sky blue towards the outside of the wings. Photography tends to misregister the blue on the wings as purplish due to light scattering. The margins of the upper wing are black and sport "long, white, hair-like scales". The male butterfly also has small circular gray spots in the submargins on the ventral surface of the whitish ventral wing surface. In the post-median and submedian areas of the ventral surface black spots mark the upper and lower wing. The male's body is a dark-blue/brown color. In females the upper wings are dark brown, but otherwise mirror males.[3]

The larvae feed exclusively on the leaves of their hostplants, Lupinus albifrons, Lupinus formosus, and Lupinus variicolor.[2] The adult Mission blue nectars from a variety of flowers, many in the sunflower family.[4]

Range

editI. i. missionensis is federally endangered and found in only a few locations.[2] Its habitat is restricted to the San Francisco Bay Area, specifically six areas, the Twin Peaks area in San Francisco County, Fort Baker, a former military installation managed by the National Park Service (NPS), in Marin County, the San Bruno Mountain area in San Mateo County, the Marin Headlands, in Golden Gate National Recreation Area (another NPS entity), Laurelwood Park and Sugarloaf Open Space in the city of San Mateo, and Skyline Ridge, also in San Mateo County.[5] San Bruno Mountain hosts the largest population of Mission blues, a butterfly commonly found around elevations of 700 feet. The coastal scrubland and grassland the Mission blue requires is found only in and around the Golden Gate of San Francisco.[6] The butterfly depends solely on three species of perennial lupine for its reproduction, the varied lupine, silver lupine, and the summer lupine. The Mission blue requires the lupine to lay their eggs and nourish the larvae. Without these species, it cannot reproduce and thus cannot survive.[7] Thus, the Mission blue's habitat parallels that of the lupine species.

Ironically, the same harmful toxins which have led to the eradication of several lupines from rangeland are responsible for the protection of the Mission blue larvae, as predators are deterred by the bitter taste. Two of the areas inhabited by the Mission blue are within the confines of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. Golden Gate staff are working to ease the invasive species problem that has helped reduce the Mission blue to the endangered species list. They work to remove non-native plants and replant the area with lupine seed along with continual monitoring of the butterfly and its host plant.[8]

Much of the area that the Mission blue once inhabited has been destroyed. The coastal sage and chaparral and the native grassland habitats have seen unnatural human development in much of the region. The San Mateo County town of Brisbane lies in what may once have been the prime habitat for the butterfly. Near Brisbane, an industrial park and rock quarry have proved damaging to the Mission blue habitat. Generally, the most negative impact is that of residential and industrial development. Aside from development, other human activities have negatively affected the butterfly's habitat. Those activities include cultivation and grazing as well as the oft human assisted abundance of invasive exotic species. Some of the more impactful exotics include the European gorse and pampas grass.[7] In the Golden Gate Recreation Area, thoroughwort is a particular invasive species which is taking over habitat once occupied by the Mission blue's lifeblood, the three species of lupine.[8] Of the threats facing the Mission blue, habitat loss due to human intervention and exotic, invasive species are the two most critical.

Residential and industrial development continually threaten Mission blue habitat, such as the 1997-2001 seismic retrofitting of the Golden Gate Bridge. Despite costing an additional US$1.2 million to comply with environmental standards, the construction project still claimed about 1,500 m2 of butterfly habitat through "incidental take", an exception provided under California law. Through a type of habitat conservation popular since a 1983 amendment to the Endangered Species Act, the incidental take is offset by off-site mitigation and restoration. In this case, the San Francisco Highway and Transportation District in cooperation with the National Park Service funded a $450,000 off-site restoration plan. The main aspect of this plan was to establish about 8 ha of Mission blue habitat in the area of the bridge project.[9]

The Mission blue was first collected in the Mission District of San Francisco in 1937. Today, a small colony occurs on Twin Peaks; the subspecies has also been found in Fort Baker, which is in Marin County. However, the majority of today's Mission blue colonies is found on San Bruno Mountain. Besides those on the mountain, other colonies have been found in San Mateo County. Those colonies have been located at elevations of 690 to 1,180 feet (210 to 360 m). Some colonies have been found in the "fog belt" of the coastal mountain range. The Mission blue colonies in the area prefer coastal chaparral and coastal grasslands which are the predominant biomes where they are found.[3]

Status

editThe Mission blue was added to the Federal Endangered Species List in 1976.[5] While the state of California has enacted an Endangered Species Act, it is quite specific about what affords its protection. Sec. 2062 of the California Endangered Species Act, under definitions, declares, "Endangered species" means a native species or subspecies of a bird, mammal, fish, amphibian, reptile, or plant which is in serious danger of becoming extinct." No provision is made for a state endangered listing in California for any insect. The Mission blue butterfly is not protected by state statute in California.[10]

Life cycle

editOnly one generation occurs per year. The butterfly lays its eggs on the leaves, buds, and seed pods of L. albifrons, L. formosus, and L. variicolor.[11] The eggs are usually laid on the upper side of new lupine leaves. Eggs generally hatch within 6 to 10 days and the first- and second-instar larvae feed on the mesophyll of the lupine plants.[5] The caterpillars, extremely small, feed for a short time and then crawl to the plant base, where they enter a dormant state, known as diapause, until the late winter or the following spring. Diapause usually begins about three weeks after eclosion and begins about the same time as the host plant shifts its energy to flower and seed production.[5] When the caterpillar comes out of its diapause and begins feeding, it occasionally sheds its skin to accommodate its growth.[11]

As the larvae feed and grow, native ants may gather and indicate the presence of larger Mission blue larvae. The ants often stand on the caterpillar and tap it with their antennae. In response, the caterpillar secretes honeydew. The ants eat honeydew and in return, through this symbiotic relationship, the ants likely ward off predators.

Once the caterpillar is fully grown, it leaves the larval stage and enters the pupal stage of development. The fully grown caterpillar forms a chrysalis after securing itself to a surface which is generally a lupine stem or leaf. It sheds its outer skin, revealing the chrysalid. This stage lasts about 10 days while the adult butterfly develops within the chrysalid. The butterfly can be sighted as early as late March in the summit of San Bruno Mountain or the Twin Peaks. They persist well into June when they can be seen perched on a lupine plant or feeding on coastal buckwheat flowers.[11] Day to day for the adult butterfly is mostly spent foraging for nectar, flying, mating, and for the females, laying eggs. Nearly equal time is spent between perching, feeding, and flying.[7] The adult Mission blue lives about a week; during this time, the females lay the eggs on the host plants. The complete Mission blue butterfly life cycle lasts one year.[5]

Host plants

edit-

The varied lupine, Lupinus variicolor

-

The silver lupine, Lupinus albifrons

-

The summer lupine, Lupinus formosus

Predators

editIn the 1983 study "Six Ecological Studies of Endangered Butterflies", R. A. Arnold found that about 35% of eggs collected in the field were being parasitized by an unknown encyrtid wasp. Other parasitic Hymenoptera have been taken from the eggs of various Icarioides species. As far as predator-prey relationships, rodents are probably the primary predator of both the larvae and pupae.[7]

Taxonomy

editThe trinomial name of the Mission blue is Icaricia icarioides missionensis, since it is a subspecies of Boisduval's blue (Icaricia icarioides). However, since that species used to be classified in the genus Plebejus, some authors use the trinomial name Plebejus icarioides missionensis.

Habitat conservation

editThe U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) has a number of habitat conservation programs in effect which includes lands traditionally inhabited by the Mission blue butterfly. A recovery plan, drawn up by the USFWS in 1984, outlined the need to protect Mission blue habitat and to repair habitat damaged by urbanization, off-highway vehicle traffic, and invasion by exotic, non-native plants.[7] An example of the type of work being done by governmental and citizen agencies can be found in the Marin Headlands at Golden Gate National Recreation Area. In addition, regular wildfires have opened new habitat conservation opportunities, as well as damaging existing ones.

References

edit- ^ "ITIS Standard Report Page: Plebejus icarioides missionensis". www.itis.gov. Retrieved 2019-06-19.

- ^ a b c Davison, Veronica. "Mission Blue Butterfly - Invertebrates, Endangered Species Accounts | Sacramento Fish & Wildlife Office". Sacramento Fish and Wildlife. Retrieved 2019-06-19.

- ^ a b Mission Blue Butterfly, Species Account, USFWS, Sacramento Office

- ^ Mission Blue Butterfly, Wildlife Field Guide, National Parks Labs

- ^ a b c d e Mission Blue Butterflies Archived 2006-10-06 at the Wayback Machine, Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy

- ^ "Mission Blue Butterfly". Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy. 2018-06-05. Retrieved 2019-06-19.

- ^ a b c d e The Biogeography of the Mission Blue butterfly Archived 2007-02-03 at the Wayback Machine, San Francisco State University, Department of Geography, Autumn 2000

- ^ a b Restoration after Solstice Fire Reduces Fuel and Improves Grassland Health (PDF). Golden Gate National Recreation Area. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-10-04. Retrieved 2006-10-15.

- ^ Giacomini, Mervin C. and Woelfel, John E. Golden Gate Update Archived 2006-10-11 at the Wayback Machine, Civil Engineering Magazine, Nov. 2000

- ^ California Endangered Species Act Archived 2006-10-06 at the Wayback Machine, CA Dept. of Fish and Game, Habitat Conservation Planning Branch

- ^ a b c Orsak, Larry J. Mission Blues, San Bruno Mountain Watch

External links

edit- Mission Blue Butterfly at the Butterfly Conservation Initiative Archived website

- Butterfly is safe, court rules, New York Times, May 15, 1985.