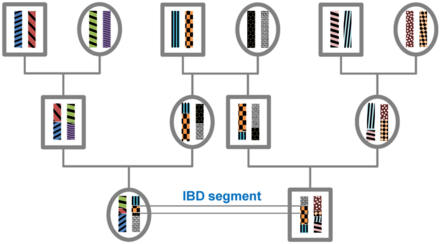

A DNA segment is identical by state (IBS) in two or more individuals if they have identical nucleotide sequences in this segment. An IBS segment is identical by descent (IBD) in two or more individuals if they have inherited it from a common ancestor without recombination, that is, the segment has the same ancestral origin in these individuals. DNA segments that are IBD are IBS per definition, but segments that are not IBD can still be IBS due to the same mutations in different individuals or recombinations that do not alter the segment.[citation needed]

Theory

editAll individuals in a finite population are related if traced back long enough and will, therefore, share segments of their genomes IBD. During meiosis segments of IBD are broken up by recombination. Therefore, the expected length of an IBD segment depends on the number of generations since the most recent common ancestor at the locus of the segment. The length of IBD segments that result from a common ancestor n generations in the past (therefore involving 2n meiosis) is exponentially distributed with mean 1/(2n) Morgans (M).[1] The expected number of IBD segments decreases with the number of generations since the common ancestor at this locus. For a specific DNA segment, the probability of being IBD decreases as 2−2n since in each meiosis the probability of transmitting this segment is 1/2.[2]

Applications

editIdentified IBD segments can be used for a wide range of purposes. As noted above the amount (length and number) of IBD sharing depends on the familial relationships between the tested individuals. Therefore, one application of IBD segment detection is to quantify relatedness.[3][4][5][6] Measurement of relatedness can be used in forensic genetics,[7] but can also increase information in genetic linkage mapping[3][8] and help to decrease bias by undocumented relationships in standard association studies.[6][9] Another application of IBD is genotype imputation and haplotype phase inference.[10][11][12] Long shared segments of IBD, which are broken up by short regions may be indicative for phasing errors.[5][13]: SI

IBD mapping

editIBD mapping[3] is similar to linkage analysis, but can be performed without a known pedigree on a cohort of unrelated individuals. IBD mapping can be seen as a new form of association analysis that increases the power to map genes or genomic regions containing multiple rare disease susceptibility variants.[6][14]

Using simulated data, Browning and Thompson showed that IBD mapping has higher power than association testing when multiple rare variants within a gene contribute to disease susceptibility.[14] Via IBD mapping, genome-wide significant regions in isolated populations as well as outbred populations were found while standard association tests failed.[11][15] Houwen et al. used IBD sharing to identify the chromosomal location of a gene responsible for benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis in an isolated fishing population.[16] Kenny et al. also used an isolated population to fine-map a signal found by a genome-wide association study (GWAS) of plasma plant sterol (PPS) levels, a surrogate measure of cholesterol absorption from the intestine.[17] Francks et al. was able to identify a potential susceptibility locus for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder with genotype data of case-control samples.[18] Lin et al. found a genome-wide significant linkage signal in a dataset of multiple sclerosis patients.[19] Letouzé et al. used IBD mapping to look for founder mutations in cancer samples.[20]

IBD in population genetics

editDetection of natural selection in the human genome is also possible via detected IBD segments. Selection will usually tend to increase the number of IBD segments among individuals in a population. By scanning for regions with excess IBD sharing, regions in the human genome that have been under strong, very recent selection can be identified.[21][22]

In addition to that, IBD segments can be useful for measuring and identifying other influences on population structure.[6][23][24][25][26] Gusev et al. showed that IBD segments can be used with additional modeling to estimate demographic history including bottlenecks and admixture.[24] Using similar models Palamara et al. and Carmi et al. reconstructed the demographic history of Ashkenazi Jewish and Kenyan Maasai individuals.[25][26][27] Botigué et al. investigated differences in African ancestry among European populations.[28] Ralph and Coop used IBD detection to quantify the common ancestry of different European populations[29] and Gravel et al. similarly tried to draw conclusions of the genetic history of populations in the Americas.[30] Ringbauer et al. utilized geographic structure of IBD segments to estimate dispersal within Eastern Europe during the last centuries.[31] Using the 1000 Genomes data Hochreiter found differences in IBD sharing between African, Asian and European populations as well as IBD segments that are shared with ancient genomes like the Neanderthal or Denisova.[13]

Methods and software

editPrograms for the detection of IBD segments in unrelated individuals:

- RAPID: Ultra-fast Identity by Descent Detection in Biobank-Scale Cohorts using Positional Burrows–Wheeler Transform [32]

- Parente: identifies IBD segments between pairs of individuals in unphased genotype data[33]

- BEAGLE/fastIBD: finds segments of IBD between pairs of individuals in genome-wide SNP data[34]

- BEAGLE/RefinedIBD: finds IBD segments in pairs of individuals using a hashing method and evaluates their significance via a likelihood ratio[35]

- IBDseq: detects pairwise IBD segments in sequencing data[36]

- GERMLINE: discovers in linear-time IBD segments in pairs of individuals[5]

- DASH: builds upon pairwise IBD segments to infer clusters of individuals likely to be sharing a single haplotype[15]

- PLINK: is a tool set for whole genome association and population-based linkage analyses including a method for pairwise IBD segment detection[6]

- Relate: estimates the probability of IBD between pairs of individuals at a specific locus using SNPs[3]

- MCMC_IBDfinder: is based on Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) for finding IBD segments in multiple individuals[37]

- IBD-Groupon: detects group-wise IBD segments based on pairwise IBD relationships[38]

- HapFABIA: identifies very short IBD segments characterized by rare variants in large sequencing data simultaneously in multiple individuals[13]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Browning, S. R. (2008). "Estimation of Pairwise Identity by Descent from Dense Genetic Marker Data in a Population Sample of Haplotypes". Genetics. 178 (4): 2123–2132. doi:10.1534/genetics.107.084624. PMC 2323802. PMID 18430938.

- ^ Thompson, E. A. (2008). "The IBD process along four chromosomes". Theoretical Population Biology. 73 (3): 369–373. doi:10.1016/j.tpb.2007.11.011. PMC 2518088. PMID 18282591.

- ^ a b c d Albrechtsen, A.; Sand Korneliussen, T.; Moltke, I.; Van Overseem Hansen, T.; Nielsen, F. C.; Nielsen, R. (2009). "Relatedness mapping and tracts of relatedness for genome-wide data in the presence of linkage disequilibrium". Genetic Epidemiology. 33 (3): 266–274. doi:10.1002/gepi.20378. PMID 19025785. S2CID 12029712.

- ^ Browning, S. R.; Browning, B. L. (2010). "High-Resolution Detection of Identity by Descent in Unrelated Individuals". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 86 (4): 526–539. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.02.021. PMC 2850444. PMID 20303063.

- ^ a b c Gusev, A.; Lowe, J. K.; Stoffel, M.; Daly, M. J.; Altshuler, D.; Breslow, J. L.; Friedman, J. M.; Pe'Er, I. (2008). "Whole population, genome-wide mapping of hidden relatedness". Genome Research. 19 (2): 318–326. doi:10.1101/gr.081398.108. PMC 2652213. PMID 18971310.

- ^ a b c d e Purcell, S.; Neale, B.; Todd-Brown, K.; Thomas, L.; Ferreira, M. A. R.; Bender, D.; Maller, J.; Sklar, P.; De Bakker, P. I. W.; Daly, M. J.; Sham, P. C. (2007). "PLINK: A Tool Set for Whole-Genome Association and Population-Based Linkage Analyses". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 81 (3): 559–575. doi:10.1086/519795. PMC 1950838. PMID 17701901.

- ^ Ian W. Evett; Bruce S. Weir (January 1998). Interpreting DNA Evidence: Statistical Genetics for Forensic Scientists. Sinauer Associates, Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-87893-155-2.

- ^ Leutenegger, A.; Prum, B.; Genin, E.; Verny, C.; Lemainque, A.; Clergetdarpoux, F.; Thompson, E. (2003). "Estimation of the Inbreeding Coefficient through Use of Genomic Data". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 73 (3): 516–523. doi:10.1086/378207. PMC 1180677. PMID 12900793.

- ^ Voight, B. F.; Pritchard, J. K. (2005). "Confounding from Cryptic Relatedness in Case-Control Association Studies". PLOS Genetics. 1 (3): e32. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0010032. PMC 1200427. PMID 16151517.

- ^ Kong, A.; Masson, G.; Frigge, M. L.; Gylfason, A.; Zusmanovich, P.; Thorleifsson, G.; Olason, P. I.; Ingason, A.; Steinberg, S.; Rafnar, T.; Sulem, P.; Mouy, M.; Jonsson, F.; Thorsteinsdottir, U.; Gudbjartsson, D. F.; Stefansson, H.; Stefansson, K. (2008). "Detection of sharing by descent, long-range phasing and haplotype imputation". Nature Genetics. 40 (9): 1068–1075. doi:10.1038/ng.216. PMC 4540081. PMID 19165921.

- ^ a b Gusev, A.; Shah, M. J.; Kenny, E. E.; Ramachandran, A.; Lowe, J. K.; Salit, J.; Lee, C. C.; Levandowsky, E. C.; Weaver, T. N.; Doan, Q. C.; Peckham, H. E.; McLaughlin, S. F.; Lyons, M. R.; Sheth, V. N.; Stoffel, M.; De La Vega, F. M.; Friedman, J. M.; Breslow, J. L.; Pe'Er, I. (2011). "Low-Pass Genome-Wide Sequencing and Variant Inference Using Identity-by-Descent in an Isolated Human Population". Genetics. 190 (2): 679–689. doi:10.1534/genetics.111.134874. PMC 3276614. PMID 22135348.

- ^ Browning, B. L.; Browning, S. R. (2009). "A Unified Approach to Genotype Imputation and Haplotype-Phase Inference for Large Data Sets of Trios and Unrelated Individuals". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 84 (2): 210–223. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.01.005. PMC 2668004. PMID 19200528.

- ^ a b c Hochreiter, S. (2013). "HapFABIA: Identification of very short segments of identity by descent characterized by rare variants in large sequencing data". Nucleic Acids Research. 41 (22): e202. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt1013. PMC 3905877. PMID 24174545.

- ^ a b Browning, S. R.; Thompson, E. A. (2012). "Detecting Rare Variant Associations by Identity-by-Descent Mapping in Case-Control Studies". Genetics. 190 (4): 1521–1531. doi:10.1534/genetics.111.136937. PMC 3316661. PMID 22267498.

- ^ a b Gusev, A.; Kenny, E. E.; Lowe, J. K.; Salit, J.; Saxena, R.; Kathiresan, S.; Altshuler, D. M.; Friedman, J. M.; Breslow, J. L.; Pe'Er, I. (2011). "DASH: A Method for Identical-by-Descent Haplotype Mapping Uncovers Association with Recent Variation". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 88 (6): 706–717. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.04.023. PMC 3113343. PMID 21620352.

- ^ Houwen, R. H. J.; Baharloo, S.; Blankenship, K.; Raeymaekers, P.; Juyn, J.; Sandkuijl, L. A.; Freimer, N. B. (1994). "Genome screening by searching for shared segments: Mapping a gene for benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis". Nature Genetics. 8 (4): 380–386. doi:10.1038/ng1294-380. hdl:1765/55192. PMID 7894490. S2CID 8131209.

- ^ Kenny, E. E.; Gusev, A.; Riegel, K.; Lutjohann, D.; Lowe, J. K.; Salit, J.; Maller, J. B.; Stoffel, M.; Daly, M. J.; Altshuler, D. M.; Friedman, J. M.; Breslow, J. L.; Pe'Er, I.; Sehayek, E. (2009). "Systematic haplotype analysis resolves a complex plasma plant sterol locus on the Micronesian Island of Kosrae". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (33): 13886–13891. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10613886K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0907336106. PMC 2728990. PMID 19667188.

- ^ Francks, C.; Tozzi, F.; Farmer, A.; Vincent, J. B.; Rujescu, D.; St Clair, D.; Muglia, P. (2008). "Population-based linkage analysis of schizophrenia and bipolar case–control cohorts identifies a potential susceptibility locus on 19q13". Molecular Psychiatry. 15 (3): 319–325. doi:10.1038/mp.2008.100. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0012-C935-9. PMID 18794890.

- ^ Lin, R.; Charlesworth, J.; Stankovich, J.; Perreau, V. M.; Brown, M. A.; Anzgene, B. V.; Taylor, B. V. (2013). Toland, Amanda Ewart (ed.). "Identity-by-Descent Mapping to Detect Rare Variants Conferring Susceptibility to Multiple Sclerosis". PLOS ONE. 8 (3): e56379. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...856379L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0056379. PMC 3589405. PMID 23472070.

- ^ Letouzé, E.; Sow, A.; Petel, F.; Rosati, R.; Figueiredo, B. C.; Burnichon, N.; Gimenez-Roqueplo, A. P.; Lalli, E.; De Reyniès, A. L. (2012). Mailund, Thomas (ed.). "Identity by Descent Mapping of Founder Mutations in Cancer Using High-Resolution Tumor SNP Data". PLOS ONE. 7 (5): e35897. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...735897L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0035897. PMC 3342326. PMID 22567117.

- ^ Albrechtsen, A.; Moltke, I.; Nielsen, R. (2010). "Natural Selection and the Distribution of Identity-by-Descent in the Human Genome". Genetics. 186 (1): 295–308. doi:10.1534/genetics.110.113977. PMC 2940294. PMID 20592267.

- ^ Han, L.; Abney, M. (2011). "Identity by descent estimation with dense genome-wide genotype data". Genetic Epidemiology. 35 (6): 557–567. doi:10.1002/gepi.20606. PMC 3587128. PMID 21769932.

- ^ Cockerham, C. C.; Weir, B. S. (1983). "Variance of actual inbreeding". Theoretical Population Biology. 23 (1): 85–109. doi:10.1016/0040-5809(83)90006-0. PMID 6857551.

- ^ a b Gusev, A.; Palamara, P. F.; Aponte, G.; Zhuang, Z.; Darvasi, A.; Gregersen, P.; Pe'Er, I. (2011). "The Architecture of Long-Range Haplotypes Shared within and across Populations". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 29 (2): 473–486. doi:10.1093/molbev/msr133. PMC 3350316. PMID 21984068.

- ^ a b Palamara, P. F.; Lencz, T.; Darvasi, A.; Pe’Er, I. (2012). "Length Distributions of Identity by Descent Reveal Fine-Scale Demographic History". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 91 (5): 809–822. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.08.030. PMC 3487132. PMID 23103233.

- ^ a b Palamara, P. F.; Pe'Er, I. (2013). "Inference of historical migration rates via haplotype sharing". Bioinformatics. 29 (13): i180–i188. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btt239. PMC 3694674. PMID 23812983.

- ^ Carmi, S.; Palamara, P. F.; Vacic, V.; Lencz, T.; Darvasi, A.; Pe'Er, I. (2013). "The Variance of Identity-by-Descent Sharing in the Wright-Fisher Model". Genetics. 193 (3): 911–928. arXiv:1206.4745. doi:10.1534/genetics.112.147215. PMC 3584006. PMID 23267057.

- ^ Botigue, L. R.; Henn, B. M.; Gravel, S.; Maples, B. K.; Gignoux, C. R.; Corona, E.; Atzmon, G.; Burns, E.; Ostrer, H.; Flores, C.; Bertranpetit, J.; Comas, D.; Bustamante, C. D. (2013). "Gene flow from North Africa contributes to differential human genetic diversity in southern Europe". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (29): 11791–11796. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11011791B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1306223110. PMC 3718088. PMID 23733930.

- ^ Ralph, P.; Coop, G. (2013). Tyler-Smith, Chris (ed.). "The Geography of Recent Genetic Ancestry across Europe". PLOS Biology. 11 (5): e1001555. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001555. PMC 3646727. PMID 23667324.

- ^ Gravel, S.; Zakharia, F.; Moreno-Estrada, A.; Byrnes, J. K.; Muzzio, M.; Rodriguez-Flores, J. L.; Kenny, E. E.; Gignoux, C. R.; Maples, B. K.; Guiblet, W.; Dutil, J.; Via, M.; Sandoval, K.; Bedoya, G.; 1000 Genomes, T. K.; Oleksyk, A.; Ruiz-Linares, E. G.; Burchard, J. C.; Martinez-Cruzado, C. D.; Bustamante, C. D. (2013). Williams, Scott M (ed.). "Reconstructing Native American Migrations from Whole-Genome and Whole-Exome Data". PLOS Genetics. 9 (12): e1004023. arXiv:1306.4021. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004023. PMC 3873240. PMID 24385924.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Ringbauer, Harald; Coop, Graham; Barton, Nicholas H. (2017-03-01). "Inferring Recent Demography from Isolation by Distance of Long Shared Sequence Blocks". Genetics. 205 (3): 1335–1351. doi:10.1534/genetics.116.196220. ISSN 0016-6731. PMC 5340342. PMID 28108588.

- ^ Naseri A, Liu X, Zhang S, Zhi D. Ultra-fast Identity by Descent Detection in Biobank-Scale Cohorts using Positional Burrows–Wheeler Transform BioRxiv 2017.

- ^ Rodriguez JM, Batzoglou S, Bercovici S. An accurate method for inferring relatedness in large datasets of unphased genotypes via an embedded likelihood-ratio test. RECOMB 2013, LNBI 7821:212-229.

- ^ Browning, B. L.; Browning, S. R. (2011). "A Fast, Powerful Method for Detecting Identity by Descent". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 88 (2): 173–182. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.01.010. PMC 3035716. PMID 21310274.

- ^ Browning, B. L.; Browning, S. R. (2013). "Improving the Accuracy and Efficiency of Identity-by-Descent Detection in Population Data". Genetics. 194 (2): 459–471. doi:10.1534/genetics.113.150029. PMC 3664855. PMID 23535385.

- ^ Browning, B. L.; Browning, S. R. (2013). "Detecting Identity by Descent and Estimating Genotype Error Rates in Sequence Data". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 93 (5): 840–851. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.09.014. PMC 3824133. PMID 24207118.

- ^ Moltke, I.; Albrechtsen, A.; Hansen, T. V. O.; Nielsen, F. C.; Nielsen, R. (2011). "A method for detecting IBD regions simultaneously in multiple individuals--with applications to disease genetics". Genome Research. 21 (7): 1168–1180. doi:10.1101/gr.115360.110. PMC 3129259. PMID 21493780.

- ^ He, D. (2013). "IBD-Groupon: An efficient method for detecting group-wise identity-by-descent regions simultaneously in multiple individuals based on pairwise IBD relationships". Bioinformatics. 29 (13): i162–i170. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btt237. PMC 3694672. PMID 23812980.