It has been suggested that this article be split into articles titled Trindade (island), Martim Vaz and Trindade and Martim Vaz (geography). (discuss) (December 2023) |

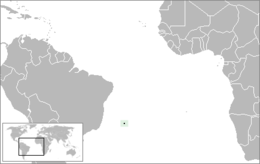

Trindade and Martim Vaz[3] (Portuguese: Trindade e Martim Vaz, pronounced [tɾĩˈdadʒi i mɐʁˈtʃĩ ˈvas]) is an archipelago located in the South Atlantic Ocean about 1,100 kilometres (680 miles) east off the coast of the Brazilian state of Espírito Santo, of which it forms a part. The archipelago has a total area of 10.4 square kilometres (4.0 square miles) and a navy-supported research station of up to 8 persons.[2][4] The archipelago consists of five islands and several rocks and stacks; Trindade is the largest island, with an area of 10.1 square kilometres (3.9 square miles); about 49 kilometres (30 miles) east of it are the tiny Martim Vaz islets, with a total area of 0.3 square kilometres (30.0 hectares).

Rocky cliffs of Trindade Island | |

| |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Atlantic Ocean |

| Coordinates | 20°31′30″S 29°19′30″W / 20.52500°S 29.32500°W |

| Archipelago | Arquipélago de Trindade e Martim Vaz |

| Total islands | 5 |

| Major islands | Trindade; Martim Vaz |

| Area | 10.4 km2 (4.0 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 620 m (2030 ft) |

| Highest point | Pico do Desejado[1] |

| Administration | |

| Region | Southeast |

| State | Espírito Santo |

| Administration | 1st Naval District of the Brazilian Navy |

| Demographics | |

| Population | Research station for up to 8 persons[2] |

| Additional information | |

| Time zone |

|

| Official website | Brazilian Navy First Naval District |

The islands are of volcanic origin and have rugged terrain. They are largely barren, except for the southern part of Trindade. They were discovered in 1502 by Portuguese explorer Estêvão da Gama and stayed Portuguese until they became part of Brazil at its independence in 1822. From 1895 to 1896, Trindade was occupied by the United Kingdom until an agreement with Brazil was reached. During the period of British occupation, Trindade was known as South Trinidad.

The islands are situated some 2,100 kilometres (1,300 miles) southwest of Ascension Island and 2,550 kilometres (1,580 miles) west of Saint Helena, and the distance to the west coast of Africa is 4,270 kilometres (2,650 miles).

Due the introduction of invasive species such as sheep, etc. the island's biodiversity has heavily deteriorated since the second half of the 20th century, with many indigenous species becoming endangered.[5]

Geography

editThe individual islands with their respective locations are given in the following:

- Ilha da Trindade (Portuguese for "Trinity Island") (20°31′30″S 29°19′30″W / 20.52500°S 29.32500°W)

- Ilhas de Martim Vaz (20°30′00″S 28°51′00″W / 20.50000°S 28.85000°W)

- Ilha do Norte ("North Island"), 300 metres (980 feet) north-northwest of Ilha da Racha, 75 metres (246 feet) high. (20°30′00″S 28°51′00″W / 20.50000°S 28.85000°W)

- Ilha da Racha ("Crack Island") or Ilha Martim Vaz, the largest, 175 metres (574 feet) high near the northwest end. The shores are strewn with boulders. (20°30′18″S 29°20′42″W / 20.50500°S 29.34500°W)

- Rochedo da Agulha ("Needle Rock"), a flat circular rock 200 metres (660 feet) northwest of Ilha da Racha, is 60 metres (200 feet) high.

- Ilha do Sul ("South Island"), 1,600 metres (5,200 feet) south of Ilha da Racha, is a rocky pinnacle. Ilha do Sul is the easternmost point of Brazil. (20°31′00″S 28°51′00″W / 20.51667°S 28.85000°W)

Trindade

editTrindade is a mountainous, desiccated volcanic island. The highest summit is Pico Desejado, near the center, 620 metres (2,030 feet) high. Nearby to the northwest are Pico da Trindade (590 m (1,940 ft)) and Pico Bonifácio (570 m (1,870 ft)). Pico Monumento, a remarkable peak in the form of a slightly inclined cylinder, rises from the west coast to 270 m (890 ft). Until around 1850, between 75 and 85% of the island was covered by a forest of Colubrina glandulosa trees, 15m in height and 40 cm trunk diameter. The introduction of non-native animals (like goats, pigs, sheep, etc.), and the indiscriminate cutting of trees, led to total extirpation of the forest, causing heavy erosion on the island, with a loss of about 1 to 2 meters of fertile soils. The effect of this devastation impaired the flow of water streams, with the depletion of several springs.

There is a small settlement in the north on the shore of a cove called Enseada dos Portugueses, supporting a garrison of the Brazilian Navy, 32 strong.

The archipelago is the main nesting site of the green sea turtle in Brazil. There are also large numbers of breeding seabirds, including the endemic subspecies of the Great frigatebird (Fregata minor nicolli) and Lesser frigatebird (F. ariel trinitatis), and it is the only Atlantic breeding site for the Trindade petrel.[6] Humpback whales have been confirmed to use the Trindade island as a nursery.[7]

History

edit16th to 18th century

editThe Trindade and Martim Vaz Islands were discovered in 1502 by Portuguese navigators led by Estêvão da Gama, and along with Brazil, became part of the Portuguese Empire.

Many visitors have been to Martim Vaz, the most famous of whom was the English astronomer Edmund Halley, who took possession of the island on behalf of the British Monarchy in 1700.[8] Wild goats and hogs, descendants of ones set free by Halley, were still found on Martim Vaz in 1939.[9]

HMS Rattlesnake, a 198-ton, 12-gun cutter-rigged sloop, was wrecked on Trindade on 21 October 1781, shortly after Commander Philippe d'Auvergne had taken over command. Rattlesnake had been ordered to survey the island to ascertain whether it would make a useful base for outward-bound Indiamen. She anchored, but that evening the wind increased and by seven o’clock she was dragging. Two hours later the first cable parted and Commander d’Auvergne club-hauled his way out, setting main and fore sails, and using the remaining anchor cable as a spring. This successfully put Rattlesnake’s head to seaward. The remaining cable was then cut, and the sloop wore round and stood out to sea. However the ground now shallowed quite rapidly and suddenly Rattlesnake struck a submerged rock. She started filling with water, so, in order to preserve the lives of the crew, d'Auvergne ran her ashore. Commodore Johnstone on board HMS Jupiter had previously wished to colonise the island and claim it for Britain, so d'Auvergne agreed to stay on the tiny island with 30 sailors, 20 captured French sailors, one French woman, some animals and supplies. They were resupplied by another ship in January 1782, then they appear to have been forgotten, as they lived on the tiny island for a year until HMS Bristol and a convoy of Indiamen, which fortuitously called there, rescued them in late December 1782.[10]: 40–45

Johnstone had made a naval base in Trindade, so Portugal reacted. They sent the 64-gun Nossa Senhora dos Prazeres, commanded by Captain of sea and war José de Melo, with 150 soldiers and artillery, but the British had already abandoned the Island.[8]

Captain La Pérouse stopped there at the outset of his 1785 voyage to the Pacific.

19th to 20th century

editIn 1839, the Ross expedition made a brief stop on Trindade, as chronicled by Robert McCormick. He described Pico Monumento as the "Nine Pin Rock".[11]

In 1889, Edward Frederick Knight went treasure hunting on the island. He was unsuccessful but he wrote a detailed description of the island and his expedition, titled The Cruise of the Alerte.

In 1893 another Franco-American, James Harden-Hickey, claimed the island and declared himself as James I, Prince of Trinidad.[12][13][14] According to James Harden-Hickey's plans, Trinidad, after being recognized as an independent country, would become a military dictatorship and have him as dictator.[15] He designed postage stamps, a national flag, and a coat of arms; established a chivalric order, the "Cross of Trinidad"; bought a schooner to transport colonists; appointed M. le Comte de la Boissiere as secretary of state; opened a consular office at 217 West 36th Street in New York City; and even issued government bonds to finance construction of infrastructure on the island. Despite his plans, his idea was ridiculed or ignored by the world.[16][17][18][19][20][21]

In July 1895, the British again tried to take possession of this strategic position in the Atlantic.[15] The British planned to use the island as a cable station.[15] However, Brazilian diplomatic efforts, along with Portuguese support[citation needed], reinstated Trindade Island to Brazilian sovereignty.

In order to clearly demonstrate sovereignty over the island, now part of the State of Espírito Santo and the municipality of Vitória, a landmark was built on 24 January 1897. Nowadays, Brazilian presence is marked by a permanent Brazilian Navy base on the main island.

In July 1910 the ship Terra Nova carrying the last expedition of Captain Robert Falcon Scott to the Antarctic arrived at the island, at the time uninhabited. Some members of the Scott's expedition explored the island with scientific purposes, and a description of it is included in The Worst Journey in the World, by Apsley Cherry-Garrard, one of the members of the expedition.

In August 1914, the Imperial German Navy established a supply base for its warships off Trindade. On 14 September 1914, the Royal Navy auxiliary cruiser HMS Carmania fought the German SMS Cap Trafalgar off Trindade in the Battle of Trindade. Carmania sank Cap Trafalgar, but sustained severe damage herself.[22]

21st Century

editTrindade was a port passing mark for the 2022 Golden Globe Race, a single-handed round-the-world yacht race.[23] In March 2023, plastic rocks called plastistone were found on Trindade.[24]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Ilha da Trindade - Infográficos e mapas Folha de S.Paulo. Retrieved on 6 June 2009.

- ^ a b "PROGRAMA DE PESQUISAS CIENTÍFICAS NA ILHA DA TRINDADE". CIRM (in Portuguese). 2017-06-30. Retrieved 2021-12-29.

- ^ National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency Web: http://geonames.nga.mil/namesgaz/

- ^ "Conheça o Arquipélago de Trindade e Martim Vaz". Mar Sem Fim. 8 February 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ "Islands off the coast of eastern Brazil - Ecoregions - WWF". World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 2021-12-29.

- ^ Fund, W. 2014. Trinidade-Martin Vaz Islands tropical forests

- ^ Siciliano S., Heissler L.V., Ilha B.E., Wickert C.J., Moura F. de J., Moreno B.I., 2016, Humpback whales off Trindade Island, Brazil: the last piece of the puzzle is in place?, SC66-b-SH-02, International Whaling Commission scientific reports, Retrieved on August 11, 2016

- ^ a b Donato, Hernâni (1996). Dicionário das Batalhas Brasileiras (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Instituição Brasileira de Difusão Cultural. p. 88. ISBN 8534800340. OCLC 36768251.

- ^ National Geographic Magazine annotated map of Atlantic Ocean, dated July 1939

- ^ Ashelford, Jane (2008). In the English Service: The Life of Philippe D'Auvergne. Jersey Heritage Trust. ISBN 978-0955250880.

- ^ M'Cormick, Robert; Franklin, John (1884). Voyages of discovery in the Arctic and Antarctic seas and round the world [microform] : being personal narratives of attempts to reach the North and South Poles, and of an open-boat expedition up the Wellington Channel in search of Sir John Franklin and Her Majesty's ships "Erebus" and "Terror", in Her Majesty's boat "Forlorn Hope", under the command of the author to which are added an autobiography, appendix, portraits, maps and numerous illustrations. Canadiana.org. London : S. Low, Marston, Searle, and Rivington. ISBN 978-0-665-09223-7.

- ^ "To Be Prince of Trinidad: He Is Baron Harden-Hickey", New York Tribune, 5 November 1893, p 1

- ^ Bryk, William, "News & Columns", New York Press, v 15 no 50 (December 10, 2002) Archived April 30, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Principality of Trinidad: John H. Flagler's Son-in-Law Is Its Sovereign, Self-Proclaimed as James I", New York Times, June 10, 1894, p 23

- ^ a b c Bryk (2002) Archived 2006-04-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Trinidad's Prince Awake: An Appeal to Washington Against Brazil and Great Britain", New York Times, August 1, 1895, p 1

- ^ "Grand Chancellor of Trinidad: Significant Phases in the Ascent of Male Comte de la Boissiere to His Elevated Diplomatic Post", New York Times, August 2, 1895, p 9

- ^ "Trinidad's Case in Washington: Courteously, the Chancellor Would Permit Britain's Cable Station and Use It, but There Is Graver Trouble", New York Times, August 7, 1895, p 1

- ^ "Trinidad's Diplomat in Action: M. de la Boissiere Asks that His Sovereign's Land Be Recognized as a Neutral Principality", New York Times, August 9, 1895, p 5

- ^ "Trinidad's Prince at Work: Grand Chancellor de la Boissiere Tells How the War Between Great Britain and Brazil Will Be Averted", New York Times, Jan 24, 1896, p 9

- ^ Flags of the World - Trindade and Martins Vaz Islands (Brazil) (sic)

- ^ Cooper, James; Arnold Kludas; Joachim Pein (1989). The Hamburg South America Line. Kendal: The World Ship Society. pp. 13–14, 64. ISBN 0-905617-50-9.

- ^ The Route from Les Sables D'Olonne, France, and Return, accessed 2022-09-29

- ^ "A Strange Plastic Rock Has Ominously Invaded 5 Continents". Popular Mechanics. 2024-01-02. Retrieved 2024-01-04.

Further reading

edit- Alves, RJV; da Silva, NG; Aguirre-Muñoz, A (2011). "Return of endemic plant populations on Trindade Island, Brazil, with comments on the fauna" (PDF). In Veitch, CR; Clout, MN; Towns, DR (eds.). Island invasives: eradication and management : proceedings of the International Conference on Island Invasives. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. pp. 259–263. OCLC 770307954. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2014-12-02.

- Olson, Storrs L. (1981). "Natural history of vertebrates on the Brazilian islands of the mid South Atlantic". National Geography Society Research Reports. 13: 481–492. hdl:10088/12766.

External links

edit- "Trindade". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- "Martin Vaz". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- TRINDADE(Spanish)