"In Flanders Fields" is a war poem in the form of a rondeau, written during the First World War by Canadian physician Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae. He was inspired to write it on May 3, 1915, after presiding over the funeral of friend and fellow soldier Lieutenant Alexis Helmer, who died in the Second Battle of Ypres. According to legend, fellow soldiers retrieved the poem after McCrae, initially dissatisfied with his work, discarded it. "In Flanders Fields" was first published on December 8 of that year in the London magazine Punch. Flanders Fields is a common English name of the World War I battlefields in Belgium and France.

| In Flanders Fields | |

|---|---|

| by John McCrae | |

| First published in | Punch |

| Form | Rondeau |

| Publication date | December 8, 1915 |

It is one of the most quoted poems from the war. As a result of its immediate popularity, parts of the poem were used in efforts and appeals to recruit soldiers and raise money selling war bonds. Its references to the red poppies that grew over the graves of fallen soldiers resulted in the remembrance poppy becoming one of the world's most recognized memorial symbols for soldiers who have died in conflict. The poem and poppy are prominent Remembrance Day symbols throughout the Commonwealth of Nations, particularly in Canada, where "In Flanders Fields" is one of the nation's best-known literary works. The poem is also widely known in the United States, where it is associated with Veterans Day and Memorial Day.

Background

editJohn McCrae was a poet and physician from Guelph, Ontario. He developed an interest in poetry at a young age and wrote throughout his life.[1] His earliest works were published in the mid-1890s in Canadian magazines and newspapers.[2] McCrae's poetry often focused on death and the peace that followed.[3]

At the age of 41, McCrae enrolled with the Canadian Expeditionary Force following the outbreak of the First World War. He had the option of joining the medical corps because of his training and age but he volunteered instead to join a fighting unit as a gunner and medical officer.[4] It was his second tour of duty in the Canadian military; he had previously fought with a volunteer force in the Second Boer War.[5] He considered himself a soldier first; his father was a military leader in Guelph and McCrae grew up believing in the duty of fighting for his country and empire.[6]

McCrae fought in the Second Battle of Ypres in the Flanders region of Belgium, where the German army launched one of the first chemical attacks in the history of war. They attacked French positions north of the Canadians with chlorine gas on April 22, 1915, but were unable to break through the Canadian line, which held for over two weeks. In a letter written to his mother, McCrae described the battle as a "nightmare",

For seventeen days and seventeen nights none of us have had our clothes off, nor our boots even, except occasionally. In all that time while I was awake, gunfire and rifle fire never ceased for sixty seconds ... And behind it all was the constant background of the sights of the dead, the wounded, the maimed, and a terrible anxiety lest the line should give way.

— McCrae[7]

Alexis Helmer, a close friend, was killed during the battle on May 2. McCrae performed the burial service himself, where he noticed how poppies quickly grew around the graves of those who died at Ypres. The next day, he composed the poem while sitting in the back of an ambulance at an Advanced Dressing Station outside Ypres.[8] This place has since become known as the John McCrae Memorial Site.

Poem

editIn Flanders Fields and Other Poems, a 1919 collection of McCrae's works, contains two versions of the poem: a printed text as below and a handwritten copy where the first line ends with "grow" instead of "blow", as discussed under Publication:[9]

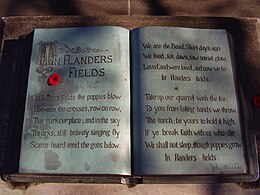

In Flanders Fields

In Flanders fields, the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie,

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

As with his earlier poems, "In Flanders Fields" continues McCrae's preoccupation with death and how it stands as the transition between the struggle of life and the peace that follows.[10] It is written from the point of view of the dead. It speaks of their sacrifice and serves as their command to the living to press on.[11] As with many of the most popular works of the First World War, it was written early in the conflict, before the romanticism of war turned to bitterness and disillusion for soldiers and civilians alike.[12]

An article by Veteran's Administration Canada provides this account of the writing of In Flanders Fields:[13]

The day before he wrote his famous poem, one of McCrae's closest friends was killed in the fighting and buried in a makeshift grave with a simple wooden cross. Wild poppies were already beginning to bloom between the crosses marking the many graves. Unable to help his friend or any of the others who had died, John McCrae gave them a voice through his poem. It was the second last poem he was to write.

Publication

editCyril Allinson was a sergeant major in McCrae's unit. While delivering the brigade's mail, he watched McCrae as he worked on the poem, noting that McCrae's eyes periodically returned to Helmer's grave as he wrote. When handed the notepad, Allinson read the poem and was so moved he immediately committed it to memory. He described it as being "almost an exact description of the scene in front of us both".[14] According to legend, McCrae was not satisfied with his work. It is said he crumpled the paper and threw it away.[15] It was retrieved by a fellow member of his unit, either Edward Morrison or J. M. Elder,[16] or Allinson.[15] McCrae was convinced to submit the poem for publication.[17] An early copy of the poem is found in the diary of Clare Gass, who was serving with McCrae as a battlefield nurse, in an entry dated October 30, 1915—nearly six weeks before the poem's first publication in the magazine Punch on December 8, 1915.[18]

Another story of the poem's origin claimed that Helmer's funeral was held on the morning of May 2, after which McCrae wrote the poem in 20 minutes. A third claim, by Morrison, was that McCrae worked on the poem as time allowed between arrivals of wounded soldiers in need of medical attention.[19] Regardless of its true origin, McCrae worked on the poem for months before considering it ready for publication.[20] He submitted it to The Spectator in London but it was rejected. It was then sent to Punch, where it was published on December 8, 1915.[17] It was published anonymously, but Punch attributed the poem to McCrae in its year-end index.[21]

The word that ends the first line of the poem has been disputed. According to Allinson, the poem began with "In Flanders Fields the poppies grow" when first written.[14] McCrae ended the second-to-last line with "grow", Punch received permission to change the wording of the opening line to end with "blow". McCrae used either word when making handwritten copies for friends and family.[22][23] Questions over how the first line should end have endured since publication. Most recently, the Bank of Canada was inundated with queries and complaints from those who believed the first line should end with "grow", when a design for the ten-dollar bill was released in 2001, with the first stanza of "In Flanders Fields", ending the first line with "blow".[24]

Popularity

editAccording to historian Paul Fussell, "In Flanders Fields" was the most popular poem of its era.[25] McCrae received numerous letters and telegrams praising his work when he was revealed as the author.[26] The poem was republished throughout the world, rapidly becoming synonymous with the sacrifice of the soldiers who died in the First World War.[11] It was translated into numerous languages, so many that McCrae himself quipped that "it needs only Chinese now, surely".[27] Its appeal was nearly universal. Soldiers took encouragement from it as a statement of their duty to those who died while people on the home front viewed it as defining the cause for which their brothers and sons were fighting.[28]

It was often used for propaganda, particularly in Canada by the Unionist Party during the 1917 federal election amidst the Conscription Crisis. French Canadians in Quebec were strongly opposed to the possibility of conscription but English Canadians voted overwhelmingly to support Prime Minister Robert Borden and the Unionist government. "In Flanders Fields" was said to have done more to "make this Dominion persevere in the duty of fighting for the world's ultimate peace than all the political speeches of the recent campaign".[29] McCrae, a staunch supporter of the empire and the war effort, was pleased with the effect his poem had on the election. He stated in a letter: "I hope I stabbed a [French] Canadian with my vote".[29]

The poem was a popular motivational tool in Great Britain, where it was used to encourage soldiers fighting against Germany, and in the United States where it was reprinted across the country. It was one of the most quoted works during the war,[12] used in many places as part of campaigns to sell war bonds, during recruiting efforts and to criticize pacifists and those who sought to profit from the war.[30] At least 55 composers in the United States set the poem "In Flanders Fields" to music by 1920, including Charles Ives, Arthur Foote, and John Philip Sousa.[31] The setting by Ives, which premiered in early 1917, is perhaps the earliest American setting.[32] Fussell criticized the poem in his work The Great War and Modern Memory (1975).[25] He noted the distinction between the pastoral tone of the first nine lines and the "recruiting-poster rhetoric" of the third stanza. Describing it as "vicious" and "stupid", Fussell called the final lines a "propaganda argument against a negotiated peace".[33]

Legacy

editMcCrae was moved to the medical corps and stationed in Boulogne, France, in June 1915 where he was promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel and placed in charge of medicine at the Number 3 Canadian General Hospital.[34] He was promoted to the acting rank of colonel on January 13, 1918, and named Consulting Physician to the British Armies in France. The years of war had worn McCrae down; he contracted pneumonia that day and later came down with cerebral meningitis. On January 28, 1918, he died at the military hospital in Wimereux and was buried there with full military honours.[35] A book of his works, featuring "In Flanders Fields", was published the following year.[36]

"In Flanders Fields" is very popular in Canada, where it is a staple of Remembrance Day ceremonies and may be the best-known literary piece among English Canadians.[36] It has an official French adaptation, entitled "Au champ d'honneur", written by Jean Pariseau and used by the Canadian government in French and bilingual ceremonies.[37] With an excerpted appearance on the ten-dollar bill from 2001 to 2013, the Royal Canadian Mint has released poppy-themed quarters on several occasions. A version minted in 2004 featured a red poppy in the centre and is considered the first multi-coloured circulation coin in the world.[38] To mark the poem's centennial in 2015, a coloured and uncoloured poppy quarter and a "toonie" ($2 coin) were issued as circulation coins, as well as other collector coins.[39][40] Among its uses in popular culture, the lines "to you from failing hands we throw / the torch, be yours to hold it high" has served as a motto for the Montreal Canadiens hockey club since 1940.[41]

Canada Post honoured the 50th anniversary of John McCrae's death with a stamp in 1968 and marked the centennial of his famous poem in 2015. Other Canadian stamps have featured the poppy, including ones in 1975, 2001, 2009,[42] 2013 and 2014. Other postal authorities have employed the poppy as a symbol of remembrance, including those of Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and the United Kingdom.[43]

McCrae's birthplace in Guelph, Ontario has been converted into a museum dedicated to his life and the war.[44] McCrae was named a National Historic Person in 1946, and his house was listed as a National Historic Site in 1966.[45][46]

In Belgium, the In Flanders Fields Museum in Ypres, named after the poem and devoted to the First World War, is situated in one of Flanders' largest tourist areas.[47] A monument commemorating the writing of the poem is located at Essex Farm Commonwealth War Graves Commission Cemetery, which is thought to have been the location of Helmer's burial and lies within the John McCrae Memorial Site.[48]

Despite its fame, "In Flanders Fields" is often ignored by academics teaching and discussing Canadian literature.[36] The poem is sometimes viewed as an anachronism; it spoke of glory and honour in a war that has since become synonymous with the futility of trench warfare and the slaughter produced by 20th-century weaponry.[30] Nancy Holmes, professor at the University of British Columbia, speculated that its patriotic nature and use as a tool for propaganda may have led literary critics to view it as a national symbol or anthem rather than a poem.[36]

Remembrance poppies

editThe red poppies that McCrae referred to had been associated with conflict since the Napoleonic Wars when a writer of that time first noted how the poppies grew over the graves of soldiers.[49] The damage done to the landscape in Flanders during the battle greatly increased the lime content in the surface soil, leaving the poppy as one of the few plants able to grow in the region.[50]

Inspired by "In Flanders Fields", American professor Moina Michael resolved at the war's conclusion in 1918 to wear a red poppy year-round to honour the soldiers who had died in the war. She also wrote a poem in response called "We Shall Keep the Faith".[51] She distributed silk poppies to her peers and campaigned to have them adopted as an official symbol of remembrance by the American Legion. Madame E. Guérin attended the 1920 convention where the Legion supported Michael's proposal and was inspired to sell poppies in her native France to raise money for the war's orphans.[52] In 1921, Guérin sent poppy sellers to London ahead of Armistice Day, attracting the attention of Field Marshal Douglas Haig. A co-founder of The Royal British Legion, Haig supported and encouraged the sale.[50] The practice quickly spread throughout the British Empire. The wearing of poppies in the days leading up to Remembrance Day remains popular in many areas of the Commonwealth of Nations, particularly United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa and in the days leading up to ANZAC Day in Australia and New Zealand.[52]

See also

editReferences

editFootnotes

- ^ Prescott 1985, p. 11

- ^ The early years, Veterans Affairs Canada, archived from the original on March 7, 2012, retrieved February 6, 2012

- ^ Prescott 1985, p. 21

- ^ Gillmor 2001, pp. 91–92

- ^ Prescott 1985, p. 31

- ^ Bassett 1984, p. 14

- ^ In Flanders Fields, Veterans Affairs Canada, archived from the original on October 7, 2012, retrieved February 6, 2012

- ^ Gillmor 2001, p. 93

- ^ McCrae, John (1919). In Flanders Fields and Other Poems. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. p. 3.

- ^ Prescott 1985, p. 106

- ^ a b "In Flanders Fields", The New York Times, December 18, 1921, retrieved February 7, 2012

- ^ a b Prescott 1985, pp. 105–106

- ^ "In memory of Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae". VAC. November 7, 2019. Retrieved December 11, 2019.

- ^ a b "Poem depicts war scenes", Regina Leader-Post, p. 13, November 12, 1968, retrieved February 7, 2012

- ^ a b "Forever there... In Flanders Fields", The Journal Opinion, p. 8, March 29, 2006, retrieved February 7, 2012

- ^ The Red Poppy, The Australian Army, archived from the original on February 26, 2012, retrieved February 7, 2012

- ^ a b Prescott 1985, p. 96

- ^ "Clare Gass Fonds". McGill Library Archival Catalogue. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- ^ Prescott 1985, pp. 95–96

- ^ Gillmor 2001, p. 94

- ^ Prescott 1985, p. 105

- ^ Brennan, Pat (November 10, 2009), "Guelph house commemorates Flanders' poet McCrae", Toronto Star, retrieved February 7, 2012

- ^ Dysert, Anna (November 11, 2015). "'In Flanders fields' at the Osler Library". De re medica : News from the Osler Library of the History of Medicine. Retrieved February 13, 2018.

- ^ "Flanders poppies blow up furor in Canada", Los Angeles Times, p. A38, February 11, 2001, retrieved February 11, 2012

- ^ a b Fussell 2009, p. 315

- ^ Ragner, Bernhard (January 30, 1938), "A tribute in Flanders Fields", The New York Times Magazine, p. 14, retrieved February 7, 2012

- ^ Bassett 1984, p. 50

- ^ Bassett 1984, p. 49

- ^ a b Prescott 1985, p. 125

- ^ a b Prescott 1985, p. 133

- ^ Ward, Jennifer A. (March 13, 2014). "American Musical Settings of "In Flanders Fields" and the Great War". Journal of Musicological Research. 33 (1–3): 96–129. doi:10.1080/01411896.2014.878566. S2CID 161990222.

- ^ In Flanders Fields (Song Collection), Library of Congress, retrieved February 20, 2012

- ^ Fussell 2009, pp. 314–315

- ^ Prescott 1985, p. 101

- ^ Bassett 1984, pp. 59–60

- ^ a b c d Holmes, Nancy (2005), ""In Flanders Fields" – Canada's Official Poem: Breaking Faith", Studies in Canadian Literature, 30 (1), University of New Brunswick, retrieved February 11, 2012

- ^ Le Canada pendant la Première Guerre mondiale et la route vers la crête de Vimy (in French), Veterans Affairs Canada, archived from the original on October 26, 2012, retrieved February 8, 2012

- ^ A symbol of remembrance, Royal Canadian Mint, archived from the original on September 18, 2012, retrieved February 11, 2012

- ^ Never forget with the 2015 Remembrance coins, Royal Canadian Mint order form, October 2015

- ^ Royal Canadian Mint Commemorates 100th Anniversary of In Flanders Fields with Silver Collector Coins Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Royal Canadian Mint news release, April 30, 2015

- ^ Last game at the Montreal Forum, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, retrieved February 11, 2012

- ^ "Lest We Forget". Canada Post. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ "In Flanders Fields stamp issue". Canada Post. April 29, 2015. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ Hill, Valerie (November 7, 1998), "Lest We Forget McCrae House keeps realities of war alive", Kitchener Record, retrieved February 20, 2012[dead link]

- ^ McCrae, Lieutenant-Colonel John National Historic Person, Parks Canada, 2012

- ^ McCrae House National Historic Site, Parks Canada, 2012

- ^ Nieuw streekbezoekerscentrum Ieper officieel geopend (in Dutch), Knack.be, February 5, 2012, archived from the original on February 7, 2012, retrieved February 13, 2012

- ^ "Ieper (Ypres) – Belgium – Nearby site: Essex Farm Cemetery, Boezinge – Lieutenant Colonel McCrae". www.ww1westernfront.gov.au. Department of Veterans' Affairs and Board of Studies, New South Wales. July 2013. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved April 8, 2016.

- ^ Remembrance Day: Lest we forget, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, November 10, 2010, retrieved February 8, 2012

- ^ a b "Where did the idea to sell poppies come from?", BBC News, November 10, 2006, retrieved February 8, 2012

- ^ Moina Michael, Digital Library of Georgia, retrieved February 8, 2012

- ^ a b Rahman, Rema (November 9, 2011), "Who, What, Why: Which countries wear poppies?", BBC News, retrieved February 8, 2012

Bibliography

- Bassett, John (1984), The Canadians: John McCrae, Markham, Ontario: Fitzhenry & Whiteside Limited, ISBN 0-88902-651-3

- Fussell, Paul (2009) [1975], The Great War and Modern Memory (Illustrated Edition), New York: Stirling Publishing, ISBN 978-0-19-513331-8

- Gillmor, Don (2001), Canada: A People's History, vol. two, Toronto, Ontario: McClelland & Stewart, ISBN 0-7710-3340-0

- McCrae, John (1919), In Flanders Fields and Other Poems, Arcturus Publishing (reprint 2008), ISBN 1-84193-994-3, retrieved February 7, 2012

- Prescott, John F. (1985), In Flanders Fields: The Story of John McCrae, Erin, Ontario: Boston Mills Press, ISBN 0-919783-07-4

External links

edit- In Flanders Fields And Other Poems at Faded Page (Canada)

- Royal Canadian Legion web page about John McCrae, "In Flanders Fields", and the custom of wearing poppies

- In Flanders Fields, choral piece by composer Bradley Nelson, commissioned by Fresno State Chamber Singers and Chico State Chamber Singers of California State University

- In Flander's fields by Lt. Col. John McCrae, M.D. and America's answer by R. W. Lillard, 1914–1918. Hamilton, Ont. : Commercial Engravers, 1918. 8 p. Accessed 4 January 2014, in PDF format.

- In Flanders Fields public domain audiobook at LibriVox

- Andrew Macphail Fonds McGill University Library & Archives.

- Clare Gass Fonds McGill University Library & Archives.