Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, written by herself is an autobiography by Harriet Jacobs, a mother and fugitive slave, published in 1861 by L. Maria Child, who edited the book for its author. Jacobs used the pseudonym Linda Brent. The book documents Jacobs' life as a slave and how she gained freedom for herself and for her children. Jacobs contributed to the genre of slave narrative by using the techniques of sentimental novels "to address race and gender issues."[1] She explores the struggles and sexual abuse that female slaves faced as well as their efforts to practice motherhood and protect their children when their children might be sold away.

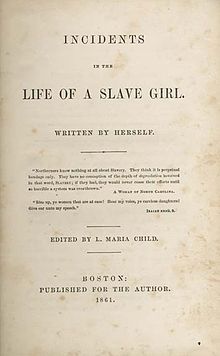

Frontispiece of the first edition | |

| Author | Harriet Jacobs |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Slave narrative |

| Set in | North Carolina and New York City, 1813–1842 |

| Publisher | Thayer & Eldridge |

Publication date | 1861 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print: hardback |

| 305.567092 | |

| LC Class | E444.J17 A3 |

| Text | Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl at Wikisource |

In the book, Jacobs addresses White Northern women who fail to comprehend the evils of slavery. She makes direct appeals to their humanity to expand their knowledge and influence their thoughts about slavery as an institution.

Jacobs composed Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl after her escape to New York, while living and working at Idlewild, the home of writer and publisher Nathaniel Parker Willis.[2]

Historical context

editBiographical background

editHarriet Jacobs was born into slavery in Edenton, North Carolina in 1813. When she was a child, her mistress taught her to read and write, skills that were extremely rare among slaves. At twelve years old, she fell into the hands of an abusive owner who harassed her sexually. When he threatened to sell her children, she hid in a tiny crawlspace under the roof of her grandmother's house. After staying there for seven years, spending much of her time reading the Bible and also newspapers,[4] she finally managed to escape to New York in 1842.

Her brother, John S. Jacobs, who had also managed to escape from slavery, became more and more involved with the abolitionists led by William Lloyd Garrison, going on several anti-slavery lecturing tours from 1847 onwards.[5] In 1849/50, Harriet Jacobs helped her brother running the Anti-Slavery Office and Reading Room in Rochester, New York, being in close contact with abolitionists and feminists like Frederick Douglass and Amy and Isaac Post. During that time she had the opportunity to read abolitionist literature and become acquainted with anti-slavery theory. In her autobiography she describes the effects of this period in her life: "The more my mind had become enlightened, the more difficult it was for me to consider myself an article of property."[6] Urged by her brother and by Amy Post, she started to write her autobiography in 1853, finishing the manuscript in 1858. During that time she was working as a nanny for the children of N. P. Willis. Still, she didn't find a publisher until 1860, when Thayer & Eldridge agreed to publish her manuscript and initiated her contact with Lydia Maria Child, who became the editor of the book, which was finally published in January 1861.

Abolitionist and African-American literature

editWhen Jacobs started working on Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl in 1853, many works by abolitionist and African-American writers were already in print. In 1831 William Lloyd Garrison had started the publication of his weekly The Liberator.

In 1845, Frederick Douglass had published his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Written by Himself, which became a bestseller and paved the way for subsequent slave narratives.[7]

The White abolitionist Harriet Beecher Stowe published Uncle Tom's Cabin in 1852, artfully combining the genres of slave narratives and sentimental novels.[8] Although a work of fiction, Stowe based her novel on several accounts by eyewitnesses.

However, the relationship between Black and White abolitionist writers was not without problems. Garrison supplied a preface to Douglass's Narrative that would later be analyzed as latently racist,[9] and the relationship between the two male abolitionists deteriorated when Garrison was less than supportive to the idea of Douglass starting his own newspaper.[10] That Stowe's book became an instant bestseller was in part due to the fact that she shared her readers' racist mindset, explicitly stating that Black people were intellectually inferior and modeling the character of her protagonist, Uncle Tom, accordingly.[11] When Jacobs suggested to Stowe that Stowe transform her story into a book, Jacobs perceived Stowe's reaction as a racist insult, which she analyzed in a letter to her White friend Amy Post.[12]

Cult of True Womanhood

editIn the antebellum period, the Cult of True Womanhood was prevalent among upper and middle-class White women. This set of ideals, as described by Barbara Welter, asserted that all women possessed (or should possess) the virtues of piety, purity, domesticity, and submissiveness.[13] Venetria K. Patton explains that Jacobs and Harriet E. Wilson, who wrote Our Nig, reconfigured the genres of slave narrative and sentimental novel, claiming the titles of "woman and mother" for Black females, and suggesting that society's definition of womanhood was too narrow.[1] They argued and "remodeled" Stowe's descriptions of Black maternity.[14]

They also showed that the institution of slavery made it impossible for African-American women to control their virtue, as they were subject to the social and economic power of men.[15] Jacobs showed that enslaved women had a different experience of motherhood but had strong feelings as mothers despite the constraints of their position.[16]

Jacobs was clearly aware of the womanly virtues, as she referred to them as a means to appeal to female abolitionists to spur them into action to help protect enslaved Black women and their children. In the narrative, she explains life events that prevent Linda Brent from practicing these values, although she wants to. For example, as she cannot have a home of her own for her family, she cannot practice domestic virtues.

Character list

editLinda Brent is Harriet Jacobs, the narrator and protagonist.

Aunt Martha is Molly Horniblow, Linda's maternal grandmother. After briefly talking of her earliest childhood, her parents and her brother, Jacobs begins her book with the history of her grandmother. At the end of the book, Jacobs relates the death of her grandmother in 1853, soon after Jacobs had obtained her legal freedom, using the very last sentence to mention the "tender memories of my good old grandmother." Molly Horniblow obtained her freedom in 1828, when Jacobs was about 15 years old, because friends of hers bought her with the money she had earned by working at night.

Benjamin is Joseph Horniblow, Aunt Martha's youngest child and Linda's uncle. Chapter 4, The Slave Who Dared to Feel like a Man, is largely dedicated to his story: Being only a few years older than Linda, "he seemed more like my brother than my uncle".[17] Linda and Benjamin share the longing for freedom. When his master attempts to whip him, he throws him to the ground and then runs away to avoid the punishment of a public whipping. He is caught, paraded in chains through Edenton, and put into jail. Although his mother entreats him to ask forgiveness of his master, he proudly refuses and is finally sold to New Orleans. Later, his brother Mark (called Philipp in the book), unexpectedly meets him in New York, learning that he has escaped again, but is in a very poor physical condition and without support. After that meeting, the family never heard from him again. Linda and her brother see him as a hero. Both of them would later name their son for him.[18]

William is John S. Jacobs, Linda's brother, to whom she is close.

Benny is Joseph Jacobs, Linda's son.

Ellen is Louisa Matilda Jacobs, Linda's daughter.

Dr. Flint is Dr. James Norcom, Linda's master and tormentor. J. F. Yellin, after researching his surviving private letters and notes, writes about his personality: "Norcom was a loving and dominating husband and father. In his serious and sophisticated interest in medicine, his commitment as a physician, and his educated discourse, he appears unlike the villain Jacobs portrays. But his humorlessness, his egoism, his insistently controlling relationships with his wife and children ... suggest the portrait Jacobs draws. This impression is supported by ... his unforgiving fury against those he viewed as enemies. It is underscored by his admitted passionate responses to women."[19]

Mrs. Flint is Mary "Maria" Norcom, Linda's mistress and Dr. Flint's wife.

Emily Flint is Mary Matilda Norcom, Dr. Flint's daughter and Linda's legal owner.

Mr. Sands is Samuel Tredwell Sawyer, Linda's White sexual partner and the father of her children, Benny and Ellen.

Mr. Bruce is Nathaniel Parker Willis.

The second Mrs. Bruce is Cornelia Grinnel Willis.

Overview

editChapters 1 and 2 describe the narrator's childhood and the story of her grandmother until she got her freedom. The narrator's story is then continued in chapters 4 to 7, which tell of the longing for freedom she shares with her uncle Benjamin and her brother William, Benjamin's escape, the sexual harassment by Dr. Flint, the jealousy of his wife, and the lover who she is forbidden to marry. Chapters 10 and 11 tell of her affair with Mr. Sands and the birth of her first child. Chapters 14 to 21 tell of the birth of her second child, her removal from the town to Flint's plantation, her flight and her concealment in her grandmother's garret. The nearly seven years she had to spend in that narrow place are described in chapters 22 to 28, the last chapters of which concentrate on the fate of family members during that time: the escape of her brother William (chapter 26), the plans made for the children (27), and the cruel treatment and death of her aunt Nancy (28). Her dramatic escape to Philadelphia is the subject of chapters 29 and 30. Chapters 31 to 36 describe her short stay in Philadelphia, her reunion with the children, her new work as nanny for the Bruce family, and her flight to Boston when she is threatened with recapture by Flint. Chapter 35 focusses on her experiences with northern racism. Her journey to England with Mr. Bruce and his baby Mary is the subject of chapter 37. Finally, chapters 38 to 41 deal with renewed threats of recapture, which are made much more serious by the Fugitive Slave Law, the "confession" of her affair with Mr. Sands to her daughter, her stay with Isaac and Amy Post in Rochester, the final attempt of her legal owner to capture her, the obtaining of her legal freedom, and the death of her grandmother.

The other chapters are dedicated to special subjects: Chapter 3 describes the hiring out and selling of slaves on New Year's Day, chapter 8 is called "What Slaves Are Taught to Think of the North", chapter 9 gives various examples of cruel treatment of slaves, chapter 12 describes the narrator's experience of the anti-Black violence in the wake of Nat Turner's Rebellion, and chapter 13 is called "The Church And Slavery".

Publication history

editEarly publication attempts

editIn May 1858, Harriet Jacobs sailed to England, hoping to find a publisher there. She carried good letters of introduction, but wasn't able to get her manuscript into print. The reasons for her failure are not clear. Yellin supposes that her contacts among the British abolitionists feared that the story of her liaison with Sawyer would be too much for Victorian Britain's prudery. Disheartened, Jacobs returned to her work at Idlewild and made no further efforts to publish her book until the fall of 1859.[20]

On October 16, 1859, the anti-slavery activist John Brown tried to incite a slave rebellion at Harper's Ferry. Brown, who was executed in December, was considered a martyr and hero by many abolitionists, among them Harriet Jacobs, who added a tribute to Brown as the final chapter to her manuscript. She then sent the manuscript to publishers Phillips and Samson in Boston. They were ready to publish it under the condition that either Nathaniel Parker Willis or Harriet Beecher Stowe would supply a preface. Jacobs was unwilling to ask Willis, who held pro-slavery views, but she asked Stowe, who declined. Soon after, the publishers failed, thus frustrating Jacobs's second attempt to get her story printed.[21]

Lydia Maria Child as the book's editor

editJacobs now contacted Thayer and Eldridge, who had recently published a sympathizing biography of John Brown.[22] Thayer and Eldridge demanded a preface by Lydia Maria Child. Jacobs confessed to Amy Post, that after suffering another rejection from Stowe, she could hardly bring herself to asking another famous writer, but she "resolved to make my last effort".[23]

Jacobs met Child in Boston, and Child not only agreed to write a preface, but also to become the editor of the book. Child then re-arranged the material according to a more chronological order. She also suggested dropping the final chapter on Brown and adding more information on the anti-black violence which occurred in Edenton after Nat Turner's 1831 rebellion. She kept contact with Jacobs via mail, but the two women failed to meet a second time during the editing process, because with Cornelia Willis passing through a dangerous pregnancy and premature birth Jacobs was not able to leave Idlewild.[24]

After the book had been stereotyped, Thayer and Eldridge, too, failed. Jacobs succeeded in buying the stereotype plates and to get the book printed and bound.[25]

In January 1861, nearly four years after she had finished the manuscript, Jacobs's Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl finally appeared before the public. The next month, her brother John S. published his own, much shorter memoir, entitled A True Tale of Slavery, in London. Both siblings relate in their respective narratives their own experiences, experiences made together, and episodes in the life of the other sibling.

In her book, Harriet Jacobs doesn't mention the town or even the state, where she was held as a slave, and changes all personal names, given names as well as family names, with the only exception of the Post couple, whose names are given correctly. However, John Jacobs (called "William" in his sister's book) mentions Edenton as his birthplace and uses the correct given names, but abbreviates most family names. So Dr. Norcom is "Dr. Flint" in Harriet's book, but "Dr. N-" in John's. An author's name is not given on the title page, but the "Preface by the author" is signed "Linda Brent" and the narrator is called by that name throughout the story.

Themes

editResistance

editA turning point in the youth of Frederick Douglass, according to his autobiographies, was the fight against his brutal master. In Jacobs's autobiography there are two slaves who dare to resist their masters physically, although such an act of resistance normally is punished most cruelly: Her uncle Joseph (called "Benjamin" in the book) throws his master to the ground when he attempts to whip him, and then runs away to avoid the punishment of a public whipping.[26] Her brother John (called "William") is still a boy, when the son of his master tries to bind and whip him. John puts up a fight and wins. Although the "young master" is hurt, John gets away with it.[27] Other slaves mentioned in the book, women as well as men, resist by running away, although some have to pay dearly for that. Jacobs's uncle Joseph is caught, paraded in chains through Edenton and put in jail, where his health suffers so much that he has to be sold for a very low price.[28] Jacobs also tells of another fugitive who is killed by the slave catchers.

While physical resistance is less of an option for enslaved women, they still have many ways of resisting. Molly Horniblow, Jacobs's beloved grandmother, should have been set free at the death of her owner in 1827. But Dr. Norcom, Jacobs's abusive master and the son-in-law and executor of the will of Molly Horniblow's owner, wants to cheat her out of her freedom, citing debts which have to be settled by selling the deceased's human property. Norcom tells the enslaved woman that he wants to sell her privately in order to save her the shame of being sold at public auction, but Molly Horniblow insists on suffering that very shame. The auction turns out according to Molly Horniblow's plans: A friend of hers offers the ridiculously low price of $50,[29] and nobody among the sympathizing White people of Edenton is willing to offer more. Soon after, Jacobs's grandmother is set free.

Both Harriet Jacobs and her brother John frustrate the threats of their master by simply choosing what was meant as a threat: When Dr. Norcom throws John into the jail, which regularly serves as the place to guard slaves that are to be sold, John sends a slave trader to his master telling him he wants to be sold.[30] When Norcom tells Harriet to choose between becoming his concubine and going to the plantation, she chooses the latter, knowing that plantation slaves are even worse off than town slaves.[31]

Harriet Jacobs also knows to fight back with words: On various occasions, she doesn't follow the pattern of submissive behavior that is expected of a slave, protesting when her master beats her and when he forbids her to marry the man she loves,[32] and even telling him that his demand of a sexual relationship is against the law of God.[33]

Pro-slavery propaganda and cruel reality

editJacobs's employer, N. P. Willis, was the founding editor of the Home Journal. Some years before she started working on her book, he had published an anonymous[34] story called "The Night Funeral of a Slave"[35] about a Northerner who witnesses a funeral of an old slave which he interprets as a sign for the love between the master and his slaves. The story ends with the conclusion drawn by the northern narrator, "that the negroes of the south are the happiest and most contented people on the face of the earth". In 1849, that story was republished by Frederick Douglass, in order to criticize pro-slavery Northerners.[36]

In her autobiography, Jacobs includes a chapter about the death and funeral of her aunt Betty (called "Nancy" in the book), commenting that "Northern travellers ... might have described this tribute of respect to the humble dead as ... a touching proof of the attachment between slaveholders and their servants",[37] but adding that the slaves might have told that imaginative traveler "a different story": The funeral had not been paid for by aunt Betty's owner, but by her brother, Jacobs's uncle Mark (called "Philipp" in the book), and Jacobs herself could neither say farewell to her dying aunt nor attend the funeral, because she would have been immediately returned to her "tormentor". Jacobs also gives the reason for her aunt's childlessness and early death: Dr. and Mrs. Norcom did not allow her enough rest, but required her services by day and night. Venetria K. Patton describes the relationship between Mrs. Norcom and Aunt Betty as a "parasitic one",[38] because Mary Horniblow, who would later become Mrs. Norcom, and aunt Betty had been "foster-sisters",[39] both being nursed by Jacobs's grandmother who had to wean her own daughter Betty early in order to have enough milk for the child of her mistress by whom Betty would eventually be "slowly murdered".[40]

Church and slavery

editAt some places, Jacobs describes religious slaves. Her grandmother teaches her grandchildren to accept their status as slaves as God's will,[41] and her prayers are mentioned at several points of the story, including Jacobs's last farewell to her before boarding the ship to freedom, when the old woman prays fervently for a successful escape.[42] While Jacobs enjoys an uneasy freedom living with her grandmother after her first pregnancy, an old enslaved man approaches her and asks her to teach him, so that he can read the Bible, stating "I only wants to read dis book, dat I may know how to live, den I hab no fear 'bout dying."[43] Jacobs also tells that during her stay in England in 1845/46 she found her way back to the religion of her upbringing: "Grace entered my heart, and I knelt at the communion table, I trust, in true humility of soul."[44]

However, she is very critical regarding the religion of the slaveholders, stating "there is a great difference between Christianity and religion at the south."[45] She describes "the contemptuous manner in which the communion [was] administered to colored people".[46] She also tells of a Methodist class leader, who in civil life is the town constable, performing the "Christian office" – as Jacobs calls it in bitter irony – of whipping slaves for a fee of 50 cents. She also criticizes "the buying and selling of slaves, by professed ministers of the gospel."[44]

Jacobs's distinction between "Christianity and religion at the south" has a parallel in Frederick Douglass's Narrative, where he distinguishes the "slaveholding religion" from "Christianity proper", between which he sees the "widest, possible difference", stating, "I love the pure, peaceable, and impartial Christianity of Christ: I therefore hate the corrupt, slaveholding, women-whipping, cradle-plundering, partial and hypocritical Christianity of this land."[47]

Incidents as a feminist book

editAccording to Yellin, Incidents has a "radical feminist content."[48] Yellin states that Incidents is linked to the then popular genre of the seduction novel. That genre, examples of which include Charlotte Temple (1791) and The Quadroons, written in 1842 by M. Lydia Child, who would later become the editor of Incidents, features the story of a virtuous, but helpless woman seduced by a man. Her failure to adhere to the standard of sexual behavior set by the "white patriarchy",[49] "inevitably" leads to her "self-destruction and death". Although Jacobs describes her sexual transgression (i.e. the liaison with Sawyer) in terms of guilt and sin, she also sees it as a "mistaken tactic in the struggle for freedom". Most important, the book does not end with self-destruction, but with liberty.[50]

According to Yellin, "a central pattern in Incidents shows white women betraying allegiances of race and class to assert their stronger allegiance to the sisterhood of all women": When Jacobs goes into hiding, a White woman who is herself a slaveholder hides her in her own house for a month, and when she is threatened with recapture, her female employer's plan to rescue her involves entrusting her own baby to Jacobs.[51]

Jacobs presents herself as struggling to build a home for herself and her children. "This endorsement of domestic values links Incidents to what has been called 'woman's fiction'",[49] in which a heroine overcomes hardships by finding the necessary resources inside herself. But unlike "woman's fiction", "Incidents is an attempt to move women to political action", thus stepping out of the domestic sphere at that time commonly held to be the proper sphere for women and joining the public sphere.[52]

Jacobs discusses "the painful personal subject" of her sexual history "in order to politicize it, to insist that the forbidden topic of sexual abuse of slave women be included in public discussions of the slavery question." In telling of her daughter's acceptance of her sexual history, she "shows black women overcoming the divisive sexual ideology of the white patriarchy".[53]

Reception

edit19th century

editThe book was promoted via the abolitionist networks and was well received by the critics. Jacobs arranged for a publication in Great Britain, which appeared in the first months of 1862, soon followed by a pirated edition.[54] "Incidents was immediately acknowledged as a contribution to Afro-American letters."[55]

The publication did not cause contempt as Jacobs had feared. On the contrary, Jacobs gained respect. Although she had used a pseudonym, in abolitionist circles she was regularly introduced with words like "Mrs. Jacobs, the author of Linda", thereby conceding her the honorific "Mrs." which normally was reserved for married women.[56] The London Daily News wrote in 1862, that Linda Brent was a true "heroine", giving an example "of endurance and persistency in the struggle for liberty" and "moral rectitude".[57]

Incidents "may well have influenced" Iola Leroy, or Shadows Uplifted, an 1892 novel by Black author Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, "which in turn helped shape the writings of Zora Neale Hurston and other foremothers of black women writing today."[55]

Still, Incidents was not republished, and "by the twentieth century both Jacobs and her book were forgotten".[58]

20th and 21st centuries

editThe new interest in women and minority issues that came with the American civil rights movement also led to the rediscovery of Incidents. The first new editions began to appear at the end of the 1960s.[59]

Prior to Jean Fagan Yellin's research in the 1980s, the accepted academic opinion, voiced by such historians as John Blassingame, was that Incidents was a fictional novel written by Lydia Maria Child. However, Yellin found and used a variety of historical documents, including from the Amy Post papers at the University of Rochester, state and local historical societies, and the Horniblow and Norcom papers at the North Carolina state archives, to establish both that Harriet Jacobs was the true author of Incidents, and that the narrative was her autobiography, not a work of fiction. Her edition of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl was published in 1987 with the endorsement of Professor John Blassingame.[60]

In 2004, Yellin published an exhaustive biography (394 pages) entitled Harriet Jacobs: A Life.

In a New York Times review of Yellin's 2004 biography, David S. Reynolds states that Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl "and Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave are commonly viewed as the two most important slave narratives."[61]

In the "Acknowledgments" of his bestselling 2016 novel, The Underground Railroad, Colson Whitehead mentions Jacobs: "Frederick Douglass and Harriet Jacobs, obviously." The heroine of the novel, Cora, has to hide in a place in the attic of a house in Jacobs's native North Carolina, where like Jacobs she is not able to stand, but like her can observe the outside life through a hole that "had been carved from the inside, the work of a previous occupant" (p. 185).[62]

In 2017 Jacobs was the subject of an episode of the Futility Closet Podcast, where her experience living in a crawlspace was compared with the wartime experience of Patrick Fowler.[63]

According to a 2017 article in Forbes magazine, a 2013 translation of Incidents by Yuki Horikoshi became a bestseller in Japan.[64]

The garret

editThe space of the garret, in which Jacobs confined herself for seven years, has been taken up as a metaphor in Black critical thought, most notably by theorist Katherine McKittrick. In her text Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle, McKittrick argues that the garret "highlights how geography is transformed by Jacobs into a usable and paradoxical space."[65] When she initially enters her "loophole of retreat," Jacobs states that "[its] continued darkness was oppressive…without one gleam of light…[and] with no object for my eye to rest upon." However, once she bores holes through the space with a gimlet, Jacobs creates for herself an oppositional perspective on the workings of the plantation—she comes to inhabit what McKittrick terms a "disembodied master-eye, seeing from nowhere."[66] The garret offers Jacobs an alternate way of seeing, allowing her to reimagine freedom while shielding her from the hypervisibility to which Black people—especially Black women—are always already subject.

Katherine McKittrick reveals how theories of geography and spatial freedom produce alternative understandings and possibilities within Black feminist thought. By centering geography in her analysis, McKittrick portrays the ways in which gendered-racial-sexual domination is spatially organized. McKittrick writes, "Recognizing black women's knowledgeable positions as integral to physical, cartographic, and experiential geographies within and through dominant spatial models also creates an analytical space for black feminist geographies: black women's political, feminist, imaginary, and creative concerns that respatialize the geographic legacy of racism-sexism."[67]

In analyzing the hiding place of Harriet Jacobs (Linda Brent) – the space of her grandmother's garret – McKittrick illuminates the tensions that exist within this space and how it occupies contradictory positions. Not only is the space of the garret one of resistance and freedom for Brent, but it is also a space of confinement and concealment. That is, the garret operates as a prison and, simultaneously, as a space of liberation. For Brent, freedom in the garret takes the form of loss of speech, movement, and consciousness. McKittrick writes, "Brent's spatial options are painful; the garret serves as a disturbing, but meaningful, response to slavery." As McKittrick reveals, the geographies of slavery are about gendered-racial-sexual captivities – in these sense, the space of the garret is both one of captivity and protection for Brent.

References

edit- ^ a b Venetria K. Patton, Women in Chains: The Legacy of Slavery in Black Women's Fiction, Albany, New York: SUNY Press, 2000, pp. 53-55

- ^ Baker, Thomas N. Nathaniel Parker Willis and the Trials of Literary Fame. New York, Oxford University Press, 2001, p. 4. ISBN 0-19-512073-6

- ^ Journal of the Civil War Era.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs: A Life. New York 2004, p. 50.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs: A Life. New York 2004, p. 93.

- ^ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself, p. 299, retrieved February 3, 2020 Yellin uses this sentence as headline and motto of chapter 7, which covers her time in Rochester. Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs: A Life. New York 2004, p. 101.

- ^ Ibram X. Kendi, Stamped from the Beginning. The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America, New York: Nation Books 2016. ISBN 978-1-5685-8464-5, pp. 183–184.

- ^ Venetria K. Patton, Women in Chains: The Legacy of Slavery in Black Women's Fiction, Albany, New York: SUNY Press, 2000, p. 55.

- ^ By Black scholar I. X. Kendi, cf. Ibram X. Kendi, Stamped from the Beginning. The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America, New York: Nation Books 2016. ISBN 978-1-5685-8464-5, p. 184.

- ^ David W. Blight, Frederick Douglass. Prophet of Freedom. New York 2018, p. 188.

- ^ Ibram X. Kendi, Stamped from the Beginning. The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America, New York: Nation Books 2016. ISBN 978-1-5685-8464-5.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs: A Life. New York 2004, pp. 119–121.

- ^ Welter, Barbara. "The Cult of True Womanhood: 1820-1860," American Quarterly 18. (1966): 151-74.

- ^ Patton (2000), Women in Chains, p. 39

- ^ Larson, Jennifer. "Converting Passive Womanhood to Active Sisterhood: Agency, Power, and Subversion in Harriet Jacobs' 'Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl’," Women's Studies 35.8 (2006): 739-756. Web. October 29, 2014

- ^ Patton (2000), Women in Chains, p. 37

- ^ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself, p. 13, retrieved March 31, 2020

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs: A Life. New York 2004, pp. 20-21.

- ^ H.Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Ed. J.F.Yellin, Cambridge 2000. Note 2 to p. 83 on p. 295.

- ^ Yellin, Life 136–140

- ^ Yellin, Life 140

- ^ The Public Life of Capt. John Brown by James Redpath.

- ^ Jacobs to Post, October 8, 1860, cf. Yellin, Life 140 and note on p. 314

- ^ Yellin, Life 140–142

- ^ Yellin, Life 142–143

- ^ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself, p. 33, retrieved February 3, 2020

- ^ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself, p. 30, retrieved February 3, 2020

- ^ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself, p. 38, retrieved February 3, 2020

- ^ According to the autobiography. According to the documentation of the sale the price was $52.25, Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs: A Life. New York 2004, p. 21.

- ^ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself, p. 95, retrieved February 3, 2020

- ^ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself, p. 129, retrieved February 3, 2020

- ^ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself, p. 61, retrieved February 3, 2020

- ^ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself, p. 115, retrieved February 3, 2020

- ^ It was signed "Viator" (Latin, "Traveller").

- ^ A reprint (from De Bow's Review, February 1856) is available online at http://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/moajrnl/acg1336.1-20.002/242.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs: A Life. New York 2004, p. 109

- ^ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself, p. 222, retrieved September 19, 2019

- ^ Venetria K. Patton, Women in Chains: The Legacy of Slavery in Black Women's Fiction, Albany, New York: SUNY Press, 2000, p. 61.

- ^ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself, pp. 220, 221, retrieved September 19, 2019

- ^ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself, p. 220, retrieved September 19, 2019

- ^ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself, p. 28, retrieved September 19, 2019

- ^ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself, pp. 235–236, retrieved September 19, 2019

- ^ When direct speech is used in the book, slaves sometimes use plantation dialect, but the main characters like Linda Brent, her brother, and even her illiterate grandmother use standard English. Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself, pp. 111–113, retrieved September 19, 2019

- ^ a b Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself, p. 278, retrieved September 19, 2019

- ^ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself, p. 115, retrieved March 6, 2020

- ^ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself, p. 115, retrieved March 6, 2020. The description itself is given on p. 103-104.

- ^ Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, p. 118, retrieved March 6, 2020

- ^ H.Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Ed. J.F.Yellin, Cambridge 2000, p. vii.

- ^ a b H.Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Ed. J.F.Yellin, Cambridge 2000, p. xxxiii.

- ^ H.Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Ed. J.F.Yellin, Cambridge 2000, p. xxxii.

- ^ H.Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Ed. J.F.Yellin, Cambridge 2000, p. xxxiv-xxxv.

- ^ H.Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Ed. J.F.Yellin, Cambridge 2000, p. xxxiv.

- ^ H.Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Ed. J.F.Yellin, Cambridge 2000, p. xvi.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs: A Life. New York 2004, pp. 151-152.

- ^ a b H.Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Ed. J.F.Yellin, Cambridge 2000, p. xxxi.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs: A Life. New York 2004, p. 161.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs: A Life. New York 2004, p. 152.

- ^ H.Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Ed. J.F.Yellin, Cambridge 2000, p. xxvii.

- ^ E.g. the edition by Mnemosyne Pub. Co., Miami, 1969, see Library of Congress Catalog.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin, Harriet Jacobs: A Life. New York 2004, pp. xv-xx; Yellin, Jean Fagan and others, eds., The Harriet Jacobs Family Papers, 2 vols. (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2008), p. xxiii.

- ^ David S. Reynolds (July 11, 2004). "To Be a Slave". the New York Times.

- ^ The parallel has been observed by Martin Ebel in a review for the Swiss Tages-Anzeiger, Wie Sklaven ihrem Schicksal entkamen. (in German).

- ^ "Futility Closet 138: Life in a Cupboard". January 23, 2017.

- ^ "Why A 19th Century American Slave Memoir Is Becoming A Bestseller In Japan's Bookstores". Forbes.com. November 15, 2017. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ^ McKittrick, Katherine (2006). Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle. University of Minnesota Press. p. xxviii.

- ^ McKittrick, Katherine (2006). Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle. University of Minnesota Press. p. 43.

- ^ McKittrick, Katherine (2006). Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle. University of Minnesota Press. p. 53.

External links

edit- Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl at Standard Ebooks

- Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Harriet Jacobs at DocSouth including Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself, her first published text, and some of her reports from her work with fugitives

- Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl public domain audiobook at LibriVox

- Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl audio edition – MP3 Streams.