The legal system of India consists of civil law, common law, customary law, religious law and corporate law within the legal framework inherited from the colonial era and various legislation first introduced by the British are still in effect in modified forms today. Since the drafting of the Indian Constitution, Indian laws also adhere to the United Nations guidelines on human rights law and the environmental law. Personal law is fairly complex, with each religion adhering to its own specific laws. In most states, registering of marriages and divorces is not compulsory. Separate laws govern Hindus including Sikhs, Jains and Buddhist, Muslims, Christians, and followers of other religions. The exception to this rule is in the state of Goa, where a uniform civil code is in place, in which all religions have a common law regarding marriages, divorces, and adoption. On February 7, 2024, the Indian state of Uttarakhand also incorporated a uniform civil code. In the first major reformist judgment for the 2010s, the Supreme Court of India banned the Islamic practice of "Triple Talaq" (a husband divorcing his wife by pronouncing the word "Talaq" thrice).[1] The landmark Supreme Court of India judgment was welcomed by women's rights activists across India.[2]

As of August 2024[update], there are about 891 Central laws as per the online repository hosted by the Legislative Department, Ministry of Law and Justice, Government of India.[3] Further, there are many State laws for each state, which can also be accessed from the same repository.

History

editAncient India represented a distinct tradition of law, and had a historically independent thought of legal theory and practice. The Dharmaśāstras played an important role. The Arthashastra, dating from 400 BC and the Manusmriti, from 100 AD, were influential treatises in India, texts that were considered authoritative legal guidance.[4] Manu's central philosophy was tolerance and pluralism, and was cited across Southeast Asia.[5]

Early in this period, which culminated in the creation of the Gupta Empire, relations with ancient Greece and Rome were not infrequent. The appearance of similar fundamental institutions of international law in various parts of the world show that they are inherent in international society, irrespective of culture and tradition.[6] Inter-State relations in the pre-Islamic period resulted in clear-cut rules of warfare of a high humanitarian standard, in rules of neutrality, of treaty law, of customary law embodied in religious charters, in exchange of embassies of a temporary or semi-permanent character.[7]

After the Muslim conquest in the Indian subcontinent, Islamic Sharia law spread with the establishment of Delhi Sultanate, Bengal Sultanate and Gujarat Sultanate.[8] The Corps of Forty also played a major role by establishing some Turkish law in India.[9]

In the 17th century, when the Mughal Empire became the world's largest economy, its sixth ruler, Aurangzeb, compiled the Fatawa-e-Alamgiri with several Arab and Iraqi Islamic scholars, which served as the main governing body in most parts of South Asia.[10][11]

With the advent of the British Raj, there was a break in tradition, and Hindu and Islamic law were abolished in favour of British common law.[12] The first royal charter for the East India Company in the 1600s granted them the ability to make laws in order to better govern its “official representatives” in India. This was a power that grew rapidly with the increase in the East India Company's influence and power over India, giving the East India Company a wider and more powerful judicial authority and jurisdiction. During the eighteenth century, the East India Company wanted a more amicable ruling system where they would not have only English Common Law dictating the laws of a state that was not English yet. They opted to have a set of laws and courts in both the interior and exterior governments where the exterior, also known as the Presidencies, was ruled by English Law, staffed by English judges and lawyers, and dealt with Englishmen. The interior, the Mofussil, dealt with native law such as Hindu and Muslim personal law, Company Regulations, and Islamic criminal law.[13] This caused issues later in history when people who were not with the East India Company and were not native to India committed crimes in India. It was not easy to find out which law systems they should be subject to. In terms of Mofussil courts, Europeans still had an advantage over Indians since they could bring suit against Indians in any mofussil court but Indians would have to go to the Supreme Court to bring suit to Europeans.[14] This was financially and logistically very hard, causing a lot of dismay in Indians. Europeans often used this system to abuse and exploit Indians in criminal and civil litigation. This system was ended in 1793 by the Bengal Government, which prohibited all Europeans from living more than ten miles from Calcutta unless they agreed to be subject to Mofussil courts.

In the early 1830s, there were motions within the House of Commons, during the debates for the renewal of the East India Company's royal charter, for a special “Select Committee” to be made to look into the East India Company's objectives and operations in India. The motions were brought to the attention of the House of Commons because there were concerns about the East India Company's effectiveness in the administration of justice and law-making. The general consensus coming out of the Select Committee was that the law in India required reform since the East India Company's current system had conflicting laws and had religious laws that did not bode well with unity. The East India Company's charter of 1833 radically changed the structure of law-making in India with regard to the legislatures, it replaced the legislatures of each region with an all-India Legislative Council that had wide jurisdiction and general legislative power.[15] This stripped the law-making authority of the Presidencies which had conflicting laws and made the law more unitary in nature. The council passed all-India laws as well as an Indian Law Commission. The progenitor of this codification was a British lawyer by the name of Thomas Macaulay who became the first Law Member, the head of the All-India Legislative Council, and the first head of the Law Commission.[16] He had gone before parliament in July 1883 to make his case as to why India's government needed reformation and, according to the minutes from the meeting, he believed that Europeans provided the grounds for representative institutions but said that “in India, you cannot have representative institutions” since they do not know “what good governance is” and the “British must be the ones to show them”.[17] Macaulay then set his sights on being the one to codify Indian law and set sail to India by the end of 1883. By the end of 1884, Macaulay and the All-India Legislative Council had officially begun the process of the codification of Indian Law.[18] This is when India's laws became more attuned with British Common Law, which came from rulings in British legal cases, and is what Judges used to decide cases.[19] This meant that India had limited, on the way to becoming zero, usage of Hindu or Islamic Laws while the law of the colonizers became the predominant form of litigation. This was seemingly problematic as it did not take into concern the pre-existing Islamic and Hindu Laws that governed their societies for a long time. However, acceptance of this new code of laws was wide in India.

As a result, the present judicial system of the country derives largely from the British system and has few, if any, connections to Indian legal institutions of the pre-British era.[20]

Constitutional and administrative law

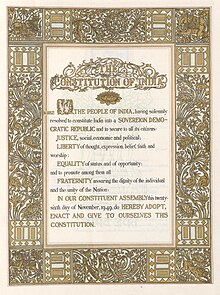

editThe Constitution of India, which came into effect on 26 January 1950 is the lengthiest written constitution in the world.[21] Although its administrative provisions are to a large extent based on the Government of India Act 1935, it also contains various other provisions that were drawn from other constitutions in the world at the time of its creation.[21] It provides details of the administration of both the Union and the States, and codifies the relations between the Federal Government and the State Governments.[22] Also incorporated into the text are a chapter on the fundamental rights of citizens, as well as a chapter on directive principles of state policy.[23]

The constitution prescribes a federal structure of government, with a clearly defined separation of legislative and executive powers between the Federation and the States.[24] Each State Government has the freedom to draft its own laws on subjects classified as state subjects.[25] Laws passed by the Parliament of India and other pre-existing central laws on subjects classified as central subjects are binding on all citizens. However, the Constitution also has certain unitary features, such as vesting power of amendment solely in the Federal Government,[26] the absence of dual citizenship,[27] and the overriding authority assumed by the Federal Government in times of emergency.[28]

Criminal law

editThe Indian Penal Code formulated by the British during the British Raj in 1860, forms the backbone of criminal law in India. This law was later repealed and replaced by Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS). The Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 governs the procedural aspects of the criminal law.[29]

Jury trials were abolished by the government in 1960 on the grounds they would be susceptible to media and public influence. This decision was based on an 8-1 acquittal of Kawas Nanavati in K. M. Nanavati vs. State of Maharashtra, which was overturned by higher courts.

In February 2011, the Supreme Court of India ruled that criminal defendants have a constitutional right to counsel.[30]

Capital punishment in India is legal. Renuka Shinde and Seema Mohan Gavit, who were guilty of kidnapping and killing at least 13 children under 6 years, are currently lodged in Yerwada Central Jail. They were also the first women in India to be given capital punishment. The last execution was conducted on 20 March 2020, where the death sentence was awarded to the convicts—Pawan Gupta, Akshay Singh Thakur, Vinay Sharma, and Mukesh Singh—by a trial court, a decision which was upheld by Delhi High Court and Supreme Court as well.[31]

Contract law

editThe main contract law in India is codified in the Indian Contract Act, which came into effect on 1 September 1872 and extends to all India. It governs entrance into contract, and effects of breach of contract. Indian Contract law is popularly known as mercantile law of India. Originally Indian Sales of Goods Act and Partnership Act were part of Indian Contract act, but due to needed amendment these acts were separated from Contract Act. The Contract act occupies the most important place in legal agreements in India.

Labour law

editIndian labour law are among the most comprehensive in the world. They have been criticised by the World Bank,[32] primarily on the grounds of the inflexibility that results from government needing to approve dismissals. In practice, there is a large informal sector of workers, between 80 or 90 per cent of the labour force, to whom labour rights are not actually available and laws are not enforced.

Company law

editThe current Indian company law was updated and recodified in the Companies Act 2013.

Tort law

editTort law in India is primarily governed by judicial precedent as in other common law jurisdictions, supplemented by statutes governing damages, civil procedure, and codifying common law torts. As in other common law jurisdictions, a tort is breach of a non-contractual duty which has caused damage to the plaintiff giving rise to a civil cause of action and for which remedy is available. If a remedy does not exist, a tort has not been committed since the rationale of tort law is to provide a remedy to the person who has been wronged.

While Indian tort law is generally derived from English law, there are certain differences between the two systems. Indian tort law uniquely includes remedies for constitutional torts, which are actions by the government that infringe upon rights enshrined in the Constitution, as well as a system of absolute liability for businesses engaged in hazardous activity.

As tort law is similar in nature across common law jurisdictions, courts have readily referred to case law from other common law jurisdictions such as the UK,[33] Australia,[34] and Canada[35] in addition to domestic precedent. However, attention is given to local norms and conditions, as well as India's distinct constitutional framework in applying foreign precedent. The legislature have also created statutes to provide for certain social conditions. Similar to other common law countries,[36] aspects of tort law have been codified.[37]

Certain conduct which gives rise to a cause of action under tort law is additionally criminalised by the Indian Penal Code[38] or other criminal legislation. Where a tort also constitutes a criminal offence, its prosecution by the state does not preclude the aggrieved party from seeking a remedy under tort law. The overlap between the two areas of law is a result of the distinct purposes each serves and the nature of the remedies each provides. Tort law aims to hold a tortfeasor accountable and consequently tort actions are brought directly by the aggrieved party in order to seek damages, whereas criminal law aims to punish and deter conduct deemed to be against the interests of society and criminal actions are thus brought by the state and penalties include imprisonment, fines, or execution.

In India, as in the majority of common law jurisdictions, the standard of proof in tort cases is the balance of probabilities as opposed to the reasonable doubt standard used in criminal cases or the preponderance of the evidence standard used in American tort litigation, although the latter is extremely similar in practice to the balance of probabilities standard. Similar to the constitutional presumption of innocence in Indian criminal law, the burden of proof is on the plaintiff in tort actions in India. India,[39] like the majority of common law jurisdictions in Asia [40][41] and Africa,[42] does not permit the use of juries in civil or criminal trials, in direct contrast to America and the Canadian common law provinces which retain civil juries as well as to jurisdictions like England and Wales or New Zealand[43] which permit juries in a limited set of tort actions.

Property law

editTax law

editIndian tax law involves several different taxes levied by different governments. Income Tax is levied by the Central Government under the Income Tax Act 1961. Customs and excise duties are also levied by the Central government. Sales tax is levied under VAT legislation at the state level. Since a new tax reform in the form of GST was levied through constitutional amendment and came into existence since 1 July 2017 which took the place of excise duties and VAT.

The authority to levy a tax is derived from the Constitution of India which allocates the power to levy various taxes between the Centre and the State. An important restriction on this power is Article 265 of the Constitution which states that "No tax shall be levied or collected except by the authority of law."[44] Therefore, each tax levied or collected has to be backed by an accompanying law, passed either by the Parliament or the State Legislature. In 2010–11, the gross tax collection amounted to ₹ 7.92 billion (Long scale), with direct tax and indirect tax contributing 56% and 44% respectively.[45]

Central Board of Direct Taxes

editThe Central Board of Direct Taxes (CBDT) is a part of the Department of Revenue in the Ministry of Finance, Government of India.[46] The CBDT provides essential inputs for policy and planning of direct taxes in India and is also responsible for administration of the direct tax laws through Income Tax Department. The CBDT is a statutory authority functioning under the Central Board of Revenue Act, 1963. It is India's official FATF unit. The Central Board of Revenue as the department apex body charged with the administration of taxes came into existence as a result of the Central Board of Revenue Act, 1924. Initially the Board was in charge of both direct and indirect taxes. However, when the administration of taxes became too unwieldy for one Board to handle, the Board was split up into two, namely the Central Board of Direct Taxes and Central Board of Excise and Customs with effect from 1 January 1964. This bifurcation was brought about by constitution of the two Boards u/s 3 of the Central Boards of Revenue Act, 1963.

Income Tax Act of 1961

editThe major tax enactment is the Income Tax Act of 1961 passed by the Parliament, which establishes and governs the taxation of the incomes of individuals and corporations.[47] This Act imposes a tax on income under the following five heads:[48]

- Income from house and property,[49]

- Income from business and profession,

- Income from salaries,

- Income in the form of Capital gains,[50] and

- Income from other sources

However, this Act may soon be repealed and be replaced with a new Act consolidating the law relating to Income Tax and Wealth Tax, the new proposed legislation is called the Direct Taxes Code (to become the Direct Taxes Code, Act 2010). Act was referred to Parliamentary standing committee which has submitted its recommendations. Act was expected to be implemented with changes from the Financial Year 2013–14 but was never enacted.[51]

Goods and Services Tax

editGoods and Services Tax (India) is a comprehensive indirect tax on manufacture, sale and consumption of goods and services throughout India to replace taxes levied by the central and state governments. It was introduced as The Constitution (One Hundred and First Amendment) Act 2016, following the passage of Constitution 101st Amendment Bill. The GST is governed by GST Council and its chairman is Nirmala Sitaraman, Finance Minister of India.

This method allows GST - registered businesses to claim tax credit to the value of GST they paid on purchase of goods or services as part of their normal commercial activity. Administrative responsibility would generally rest with a single authority to levy tax on goods and services. Exports would be considered as zero-rated supply and imports would be levied the same taxes as domestic goods and services adhering to the destination principle in addition to the Customs Duty which will not be subsumed in the GST.

Introduction of Goods and Services Tax (GST) is a significant step in the reform of indirect taxation in India. Amalgamating several Central and State taxes into a single tax would mitigate cascading or double taxation, facilitating a common national market. The simplicity of the tax should lead to easier administration and enforcement. From the consumer point of view, the biggest advantage would be in terms of a reduction in the overall tax burden on goods, which is currently estimated at 25%-30%, free movement of goods from one state to another without stopping at state borders for hours for payment of state tax or entry tax and reduction in paperwork to a large extent.

GST came into effect on 1 July 2017.

Trust law

editTrust law in India is mainly codified in the Indian Trusts Act of 1882, which came into force on 1 March 1882. It extends to the whole of India except for the state of Jammu and Kashmir and Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Indian law follows principles of English law in most areas of law, but the law of trusts is a notable exception. Indian law does not recognize "double ownership", and a beneficiary of trust property is not the equitable owner of the property in Indian law.

Family law – personal law

editFamily laws in India are different when Warren Hastings in 1772 created provisions prescribing Hindu law for Hindus and Islamic law for Muslims, for litigation relating to personal matters.[52] However, after independence, efforts have been made to modernise various aspects of personal law and bring about uniformity among various religions. Recent reform has affected custody and guardianship laws, adoption laws, succession laws, and laws concerning domestic violence and child marriage.

Hindu Law

editAs far as Hindus are concerned Hindu Law is a specific branch of law. Though the attempt made by the first parliament after independence did not succeed in bringing forth a Hindu Code comprising the entire field of Hindu family law, laws could be enacted touching upon all major areas that affect family life among Hindus in India.[53] Jains, Sikhs and Buddhists are also covered by Hindu law.

Muslim law

editIndian Muslims' personal laws are based upon the Sharia, which is thus partially applied in India,[54] and laws and legal judgements adapting and adjusting Sharia for Indian society. The portion of the fiqh applicable to Indian Muslims as personal law is termed Mohammedan law. Despite being largely uncodified, Mohammedan law has the same legal status as other codified statutes.[55] The development of the law is largely on the basis of judicial precedent, which in recent times has been subject to review by the courts.[55] The concept of the judicial precedent and of 'review by the courts' is a key component of the British common law upon which Indian law is based. The contribution of Justice V.R. Krishna Iyer in the matter of interpretation of the statutory as well as personal law is significant.

Sunni Law:

- Quran

- Sunna or Ahdis (Tradition of the Prophet)

- Ijma (Unanimous Decision of the Jurists)

- Qiyas ( Analogical deduction)

As per Shia Law:

Usooli Shia

- Quran

- Tradition (only those that have come from the family of the Prophet)

- Ijma (only those confirmed by Imams)

- Reasons

Akhbari Shia

- Tradition (only those that have come from the family of the Prophet)

Polygamy is a subject of debate from long time. It has been abolished in many Islamic countries, but still holds its legal validity in the secular country of India. Supreme court asked the central government for its views, to which it replied that polygamy should be done away with.[56][57][58]

Christian Law

editFor Christians, a distinct branch of law known as Christian Law, mostly based on specific statutes, applies.

Christian law of Succession and Divorce in India have undergone changes in recent years. The Indian Divorce (Amendment) Act of 2001 has brought in considerable changes in the grounds available for divorce. By now Christian law in India has emerged as a separate branch of law. It covers the entire spectrum of family law so far as it concerns Christians in India. Christian law, to a great extent is based on English law but there are laws that originated on the strength of customary practices and precedents.

Christian family law has now distinct sub branches like laws on marriage, divorce, restitution, judicial separation, succession, adoption, guardianship, maintenance, custody of minor children and relevance of canon law and all that regulates familial relationship.

Parsi law

editThe Parsi law[59] is the law governing the Parsi Zoroastrian community.

Nationality law

editNationality law or citizenship law is mainly codified in the Constitution of India and the Citizenship Act of 1955. Although the Constitution of India bars multiple citizenship, the Parliament of India passed on 7 January 2004, a law creating a new form of very limited dual nationality called Overseas Citizenship of India. Overseas citizens of India have no form of political rights or participation in the government, however, and there are no plans to issue to overseas citizens any form of Indian passport.

Law enforcement

editLaw enforcement in India is undertaken by numerous law enforcement agencies. Like many federal structures, the nature of the Constitution of India mandates law and order as a subject of the state, therefore the bulk of the policing lies with the respective states and territories of India.

At the federal level, the many agencies are part of the Union Ministry of Home Affairs, and support the states in their duties. Larger cities also operate metropolitan police forces, under respective state governments. All senior police officers in the state police forces, as well as those in the federal agencies, are members of the Indian Police Service (IPS) and Indian Revenue Service (IRS), two of the several kinds of civil services. They are recruited by the Union Public Service Commission.

Police Force

editThe federal police are controlled by the central Government of India. The majority of federal law enforcement agencies are controlled by the Ministry of Home Affairs. The head of each of the federal law enforcement agencies is always an Indian Police Service officer (IPS). The constitution assigns responsibility for maintaining law and order to the states and territories, and almost all routine policing—including apprehension of criminals—is carried out by state-level police forces. The constitution also permits the central government to participate in police operations and organization by authorizing the maintenance of the Indian Police Service.

Law reforms

editGovernment usually appoints Law Commission panels to study and make non-binding recommendations for the law reform. In first 65 years 1,301 obsolete laws were repealed, including 1029 old laws in 1950 by Jawaharlal Nehru and 272 old laws in 2004 by Atal Bihari Vajpayee. After that 1,824 such laws were repealed by Narendra Modi government between May 2014 to December 2017, taking the total to 3,125.[60]

Subordinate legislation in India

editSubordinate, delegated or secondary legislation covers rules, regulations, by-laws, sub-rules, orders, and notification.[61][62]

See also

editReferences

editCitations

edit- ^ Wu, Huizhong (23 August 2017). "Triple talaq: India's top court bans Islamic practice of instant divorce". CNN. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- ^ Safi, Michael; Amrit Dhillon (22 August 2017). "India court bans Islamic instant divorce in huge win for women's rights". The Guardian. Delhi. Archived from the original on 16 November 2017. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- ^ "India Code: Browsing DSpace". www.indiacode.nic.in. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ Glenn 2000, p. 255

- ^ Glenn 2000, p. 276

- ^ Alexander, C.H. (July 1952). "International Law in India". The International and Comparative Law Quarterly. 1 (3): 289–300. doi:10.1093/iclqaj/1.Pt3.289. ISSN 0020-5893.

- ^ Viswanatha, S.T., International Law in Ancient India, 1925

- ^ A. Schimmel, Islam in the Indian Subcontinent, Leiden, 1980

- ^ Embree, Ainslie (1988). Encyclopedia of Asian history. Asia Society. p. 149.

- ^ Jackson, Roy (2010). Mawlana Mawdudi and Political Islam: Authority and the Islamic State. Routledge. ISBN 9781136950360.

- ^ Chapra, Muhammad Umer (2014). Morality and Justice in Islamic Economics and Finance. Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 62–63. ISBN 9781783475728.

- ^ Glenn 2000, p. 273

- ^ Elizabeth, Kolsky. “Codification and the Rule of Colonial Difference: Criminal Procedure in British India.” (Law and History Review 23, no. 3, 2005), 631–83. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30042900.

- ^ Jain, M.P. (Journal of the Indian Law Institute 15, no. 3, 1973): 525–30. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43950226.

- ^ Kolsky, Elizabeth. “Codification and the Rule of Colonial Difference: Criminal Procedure in British India.” Law and History Review 23, no. 3 (2005): 631–83. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30042900.

- ^ Kolsky. “Codification and the Rule of Colonial Difference: Criminal Procedure in British India.”

- ^ Hansard. “East-India Company’s Charter.” EAST-INDIA COMPANY’S CHARTER. (Hansard, 10 July 1833), Accessed November 8, 2023. https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1833/jul/10/east-india-companys-charter.

- ^ Barry Wright. “Macaulay’s Indian Penal Code: Historical Context and Originating Principles.” (2016). https://carleton.ca/history/wp-content/uploads/Extract-from-Wright-for-Mar-11-talk.pdf

- ^ Patrick H. Glenn. Legal traditions of the World Sustainable Diversity in law. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- ^ Jain 2006, p. 2

- ^ a b Basu 2007, p. 41

- ^ Basu 2007, p. 42

- ^ Basu 2007, p. 43

- ^ Basu 2007, p. 53

- ^ "Laws of India". Archived from the original on 4 January 2019. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ^ Basu 2007, p. 50

- ^ Basu 2007, p. 59

- ^ Basu 2007, p. 63

- ^ "NANI PALKHIVALA - LAW RESOURCE INDIA". Archived from the original on 13 October 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ^ Dwyer Arce (28 February 2011). "India Supreme Court finds constitutional right to counsel". JURIST – Paper Chase. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- ^ [1]

- ^ "India Country Overview 2008". World Bank. 2008. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ See J. Kuppanna Chetty, Ambati Ramayya Chetty and Co. v Collector of Anantapur and Ors 1965 (2) ALT 261 at [39].

- ^ See Rattan Lal Mehta v Rajinder Kapoor [1996] ACJ 372 at [10].

- ^ See Rattan v Rajinder (1996) ACJ 372 at [8], [11], and [13].

- ^ See Defamation Act 1952 of UK and Civil Liability Act 2002 (NSW) of Australia

- ^ See Motor Vehicle Act 1988

- ^ Defamation and certain areas of negligence are criminalised in the Indian Penal Code, Act No. 45 of 1860

- ^ Jean-Louis Halpérin [in French] (25 March 2011). "Lay Justice in India" (PDF). École Normale Supérieure. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 May 2014. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- ^ George P. Landow. "Lee Kuan Yew's Opposition to Trial by Jury".

- ^ "'Judiciary', Singapore - A Country Study".

- ^ Jearey, J. (1961). Trial by Jury and Trial with the Aid of Assessors in the Superior Courts of British African Territories: II. Journal of African Law, 5(1), 36-47. doi:10.1017/S0021855300002941)

- ^ "section 16, Senior Courts Act 2016 No 48". Parliamentary Counsel Office.

- ^ Article 265 of the Indian Constitution (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 9 September 2014, retrieved 18 April 2009

- ^ "Economic growth boosts India's tax collection". Deccan Herald. Archived from the original on 28 December 2012. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ^ "Income Tax India". Archived from the original on 18 January 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ Indian Income Tax Act, 1961, archived from the original on 15 June 2013, retrieved 18 April 2009

- ^ Section 14 of Income Tax Act, archived from the original on 11 March 2009, retrieved 18 April 2009

- ^ "Treatment of income from different sources". www.incometaxindia.gov.in. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ "Treatment of income from different sources". incometaxindia.gov.in. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ "Direct Taxes Code Bill: Government keen on early enactment". The Times of India. 16 March 2012. Archived from the original on 7 July 2012.

- ^ Jain 2006, p. 530

- ^ Kalra, Kush (2013). Be Your Own Layer - Book for Layman. Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. ISBN 978-93-82652-07-6.

- ^ Fyzee 2008, p. 1

- ^ a b Fyzee 2008, p. 65

- ^ "Polygamy no longer progressive, SC told", The Hindu, 8 October 2016

- ^ "Centre opposes triple talaq, polygamy among Muslims in Supreme Court", The Financial Express, 7 October 2016, archived from the original on 10 October 2016, retrieved 8 October 2016

- ^ "Muslim women welcome govt's triple talaq stand", The Times of India, 8 October 2016, archived from the original on 28 November 2018, retrieved 8 October 2016

- ^ "Parsi Law".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Lok Sabha passes 2 bills to repeal 245 archaic laws Archived 25 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine, The Economic Times, 19 December 2017.

- ^ Kakkar, Jhalak (15 November 2012). "Parliamentary Scrutiny of Executive Rule Making" (PDF). PRS Legislative Research. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ Abraham, Arvind Kurian (16 May 2019). "Delegated Legislation: The Blindspot of the Parliament". The Wire. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ V. K. Babu Prakash (2018). "Legislative Procedures On Law, Rules And Delegated Legislation In The Indian Parliament And The State Of Kerala." The Parliamentarian 2018: Issue Three. pp. 222–225.

- ^ "The General Clauses Act, 1897" (PDF).

"National portal of India : Law & Justice".

Sources

edit- Shukla, V.N. (2013). VN Shukla's Constitution of India (12th ed.). Lucknow: Eastern Book Company. ISBN 978-93-5028-982-2.

- Basu, Durga Das (2007). Commentary on the Constitution of India (8th ed.). Nagpur: Wadhwa & Co. ISBN 978-81-8038-479-0.

- Fyzee, Asaf A.A. (2008). Outlines of Muhammadan Law (5th ed.). Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-569169-6.

- Glenn, H. Patrick (2000). Legal Traditions of the World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-876575-4.

- Jain, M.P. (2006). Outlines of Indian Legal and Constitutional History (6th ed.). Nagpur: Wadhwa & Co. ISBN 978-81-8038-264-2.

- Kane, P.V. History of Dharmaśāstra

- Shourie, A. (2012). World of Fatwas or the Sharia in action. Harpercollins India. ISBN 978-9350293423.

- Shourie, Arun (2002). Courts and their judgments: Premises, prerequisites, consequences. New Delhi: Rupa. ISBN 978-8171675579.

- Glenn, H. Patrick. Legal traditions of the World Sustainable Diversity in law. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Hansard, Historic. “East-India Company’s Charter.” EAST-INDIA COMPANY’S CHARTER. (Hansard, 10 July 1833), (HC Deb 10 July 1833 vol 19 cc479-550), Accessed November 8, 2023. https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1833/jul/10/east-india-companys-charter.

- Jain, M.P. Journal of the Indian Law Institute 15, no. 3 (1973): 525–30. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43950226.

- Kolsky, Elizabeth. “Codification and the Rule of Colonial Difference: Criminal Procedure in British India.” Law and History Review 23, no. 3 (2005): 631–83. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30042900.

- Wright, Barry. “Macaulay’s Indian Penal Code: Historical Context and Originating Principles.” (2016). https://carleton.ca/history/wp-content/uploads/Extract-from-Wright-for-Mar-11-talk.pdf