Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States government for the relocation of Native Americans who held original Indian title to their land as an independent nation-state. The concept of an Indian territory was an outcome of the U.S. federal government's 18th- and 19th-century policy of Indian removal. After the American Civil War (1861–1865), the policy of the U.S. government was one of assimilation.

| Indian Territory | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unorganized territory of independent Indian nations of the United States | |||||||||||

| 1834–1907 | |||||||||||

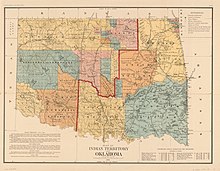

The Oklahoma (west of the red line) and Indian Territories (east of the red line) in 1890 | |||||||||||

| Capital | Tahlonteeskee (Cherokee) 1828–1839 Tahlequah (Cherokee) 1839–1906 Wewoka (Seminole) 1849–1906 Tishomingo (Chickasaw) 1852–1906 Okmulkee (Creek) 1868–1906 Pawhuska (Osage) 1872–1906 Tuskahoma (Choctaw) 1885–1906 | ||||||||||

| • Type | Devolved independent tribal governments | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

| 30 June 1834 | |||||||||||

• The 'Old Settlers' first arrivals | 1802 | ||||||||||

• Platte Purchase | 1836 | ||||||||||

• Kansas–Nebraska Act | May 30, 1854 | ||||||||||

• Name Oklahoma created | September 21, 1865 | ||||||||||

• Oklahoma Territory separated | May 2, 1890 | ||||||||||

• Annexation and Oklahoma statehood | 16 November 1907 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of |

| ||||||||||

Indian Territory later came to refer to an unorganized territory whose general borders were initially set by the Nonintercourse Act of 1834, and was the successor to the remainder of the Missouri Territory after Missouri received statehood. The borders of Indian Territory were reduced in size as various Organic Acts were passed by Congress to create organized territories of the United States. The 1906 Oklahoma Enabling Act created the single state of Oklahoma by combining Oklahoma Territory and Indian Territory, annexing and ending the existence of an unorganized independent Indian Territory as such, and formally incorporating the tribes and residents into the United States.

Before Oklahoma statehood, Indian Territory from 1890 onward comprised the territorial holdings of the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, Seminole, and other displaced Eastern American tribes. Indian reservations remain within the boundaries of U.S. states, but are largely exempt from state jurisdiction. The term "Indian country" is used to signify lands under the control of Native nations, including Indian reservations, trust lands on Oklahoma Tribal Statistical Area, or, more casually, to describe anywhere large numbers of Native Americans live.

Description and geography

editIndian Territory, also known as the Indian Territories and the Indian Country, was land in the United States reserved for the forced resettlement of Native Americans. As such, it was not a traditional territory for the tribes settled upon it.[1] The general borders were set by the Indian Intercourse Act of 1834. The territory was located in the Central United States.

While Congress passed several Organic Acts that provided a path for statehood for much of the original Indian Country, Congress never passed an Organic Act for the Indian Territory. Indian Territory was never an organized territory of the United States. In general, tribes could not sell land to non-Indians (Johnson v. McIntosh). Treaties with the tribes restricted entry of non-Indians into tribal areas; Indian tribes were largely self-governing, were suzerain nations, with established tribal governments and well established cultures. The region never had a formal government until after the American Civil War.

After the Civil War, the Southern Treaty Commission re-wrote treaties with tribes that sided with the Confederacy, reducing the territory of the Five Civilized Tribes and providing land to resettle Plains Indians and tribes of the Midwestern United States.[2] These re-written treaties included provisions for a territorial legislature with proportional representation from various tribes.

In time, the Indian Territory was reduced to what is now Oklahoma. The Organic Act of 1890 reduced Indian Territory to the lands occupied by the Five Civilized Tribes and the Tribes of the Quapaw Indian Agency (at the borders of Kansas and Missouri). The remaining western portion of the former Indian Territory became the Oklahoma Territory.

The Oklahoma Organic Act applied the laws of Nebraska to the organized Oklahoma Territory, and the laws of Arkansas to the still unorganized Indian Territory, since for years the federal U.S. District Court on the eastern borderline in Ft. Smith, Arkansas had criminal and civil jurisdiction over the territory.

History

editIndian Reserve and the Louisiana Purchase

editThe concept of an Indian territory is the successor to the British Indian Reserve, a British American territory established by the Royal Proclamation of 1763 that set aside land for use by the Native American tribes. The proclamation limited the settlement of Europeans to lands east of the Appalachian Mountains. The territory remained active until the Treaty of Paris that ended the American Revolutionary War, and the land was ceded to the United States. The Indian Reserve was slowly reduced in size via treaties with the American colonists, and after the British defeat in the Revolutionary War, the Reserve was ignored by European American settlers who slowly expanded westward.

At the time of the American Revolutionary War, many Native American tribes had long-standing relationships with the British, and were loyal to Great Britain, but they had a less-developed relationship with the American colonists. After the defeat of the British in the war, the Americans twice invaded the Ohio Country and were twice defeated. They finally defeated the Indian Western Confederacy at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794, and imposed the Treaty of Greenville, which ceded most of what is now Ohio, part of present-day Indiana, and the lands that include present-day Chicago and Detroit, to the United States federal government.

The period after the American Revolutionary War was one of rapid western expansion. The areas occupied by Native Americans in the United States were called Indian country. They were distinguished from "unorganized territory" because the areas were established by treaty.

In 1803, the United States agreed to purchase France's claim to French Louisiana for a total of $15 million (less than 3 cents per acre).[3]

President Thomas Jefferson doubted the legality of the purchase. Robert R. Livingston, the chief negotiator of the purchase, however, believed that the 3rd article of the treaty of the Louisiana Purchase would be acceptable to Congress. The 3rd article stated, in part:[4]

the inhabitants of the ceded territory shall be incorporated in the Union of the United States, and admitted as soon as possible, according to the principles of the Federal Constitution, to the enjoyment of all the rights, advantages, and immunities of citizens of the United States; and in the meantime they shall be maintained and protected in the free enjoyment of their liberty, property, and the religion which they profess.

— 8 Stat. at L. 202

This committed the U.S. government to "the ultimate, but not to the immediate, admission" of the territory as multiple states, and "postponed its incorporation into the Union to the pleasure of Congress".[4]

After the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, President Thomas Jefferson and his successors viewed much of the land west of the Mississippi River as a place to resettle the Native Americans, so that white settlers would be free to live in the lands east of the river. Indian removal became the official policy of the United States government with the passage of the 1830 Indian Removal Act, formulated by President Andrew Jackson.

When Louisiana became a state in 1812, the remaining territory was renamed Missouri Territory to avoid confusion. Arkansaw Territory, which included the present State of Arkansas plus much of the state of Oklahoma, was created out of the southern part of Missouri Territory in 1819. During negotiations with the Choctaw in 1820 for the Treaty of Doak's Stand, Andrew Jackson ceded more of Arkansas Territory to the Choctaw than he realized, from what is now Oklahoma into Arkansas, east of Ft. Smith, Arkansas.[5] The General Survey Act of 1824 allowed a survey that established the western border of Arkansas Territory 45 miles west of Ft. Smith. But this was part of the negotiated lands of Lovely's Purchase where the Cherokee, Choctaw, Creek and other tribes had been settling, and these indian nations objected strongly. In 1828 a new survey redefined the western Arkansas border just west of Ft. Smith.[6] After these redefinitions, the "Indian zone" would cover the present states of Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska and part of Iowa.[7]

Relocation and treaties

editBefore the 1871 Indian Appropriations Act, much of what was called Indian Territory was a large area in the central part of the United States whose boundaries were set by treaties between the US Government and various indigenous tribes. After 1871, the Federal Government dealt with Indian Tribes through statute; the 1871 Indian Appropriations Act also stated that "hereafter no Indian nation or tribe within the territory of the United States shall be acknowledged or recognized as an independent nation, tribe, or power with whom the United States may contract by treaty: Provided, further, That nothing herein contained shall be construed to invalidate or impair the obligation of any treaty heretofore lawfully made and ratified with any such Indian nation or tribe".[8][9][10][11]

The Indian Appropriations Act also made it a federal crime to commit murder, manslaughter, rape, assault with intent to kill, arson, burglary, or larceny within any Territory of the United States. The Supreme Court affirmed the action in 1886 in United States v. Kagama, which affirmed that the U.S. government has plenary power over Native American tribes within its borders using the rationalization that "The power of the general government over these remnants of a race once powerful ... is necessary to their protection as well as to the safety of those among whom they dwell".[12] While the federal government of the United States had previously recognized the Indian Tribes as semi-independent, "it has the right and authority, instead of controlling them by treaties, to govern them by acts of Congress, they being within the geographical limit of the United States ... The Indians [Native Americans] owe no allegiance to a State within which their reservation may be established, and the State gives them no protection."[13]

Reductions of area

editWhite settlers continued to flood into Indian country. As the population increased, the homesteaders could petition Congress for creation of a territory. This would initiate an Organic Act, which established a three-part territorial government. The governor and judiciary were appointed by the President of the United States, while the legislature was elected by citizens residing in the territory. One elected representative was allowed a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. The federal government took responsibility for territorial affairs. Later, the inhabitants of the territory could apply for admission as a full state. No such action was taken for the so-called Indian Territory, so that area was not treated as a legal territory.[7]

The reduction of the land area of Indian Territory (or Indian Country, as defined in the Indian Intercourse Act of 1834), the successor of Missouri Territory began almost immediately after its creation with:

- Wisconsin Territory formed in 1836 from lands east of the Mississippi and between the Mississippi and Missouri rivers. Wisconsin became a state in 1848

- Iowa Territory (land between the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers) was split from Wisconsin Territory in 1838 and became a state in 1846.

- Minnesota Territory was split from Iowa Territory in 1849 and part of the Minnesota Territory became the state of Minnesota in 1858

- Iowa Territory (land between the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers) was split from Wisconsin Territory in 1838 and became a state in 1846.

- Dakota Territory was organized in 1861 from the northern part of Indian Country and Minnesota Territory. The name refers to the Dakota branch of the Sioux tribes.

- North Dakota and South Dakota became separate states simultaneously in 1889.

- Present-day states of Montana and Wyoming were also part of the original Dakota Territory

Indian Country was reduced to the approximate boundaries of the current state of Oklahoma by the Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854, which created Kansas Territory and Nebraska Territory. The key boundaries of the territories were:

- 40° N the current Kansas–Nebraska border

- 37° N the current Kansas–Oklahoma (Indian Territory) border

Kansas became a state in 1861, and Nebraska became a state in 1867. In 1890 the Oklahoma Organic Act created Oklahoma Territory out of the western part of Indian Territory, in anticipation of admitting both Indian Territory and Oklahoma Territory as a future single State of Oklahoma.

Some in federal leadership, such as Secretary of State William H. Seward did not believe in the rights of Indians to continue their separate tribal governments, and vocally championed opening the area to white settlement while campaigning for Abraham Lincoln in 1860.[14] Some historians argued Seward's words steered many tribes, notably the Cherokee[15] and the Choctaw[16] into an alliance with the Confederate States.

Civil War and Reconstruction

editAt the beginning of the Civil War, Indian Territory had been essentially reduced to the boundaries of the present-day U.S. state of Oklahoma, and the primary residents of the territory were members of the Five Civilized Tribes or Plains tribes that had been relocated to the western part of the territory on land leased from the Five Civilized Tribes. In 1861, the U.S. abandoned Fort Washita, leaving the Chickasaw and Choctaw Nations defenseless against the Plains tribes. Later the same year, the Confederate States of America signed a Treaty with Choctaws and Chickasaws. Ultimately, the Five Civilized Tribes and other tribes that had been relocated to the area, signed treaties of friendship with the Confederacy.

During the Civil War, Congress gave the U.S. president the authority to, if a tribe was "in a state of actual hostility to the government of the United States... and, by proclamation, to declare all treaties with such tribe to be abrogated by such tribe"(25 USC Sec. 72). [17]

Members of the Five Civilized Tribes, and others who had relocated to the Oklahoma section of Indian Territory, fought primarily on the side of the Confederacy during the American Civil War in Indian territory. Brigadier General Stand Watie, a Confederate commander of the Cherokee Nation, became the last Confederate general to surrender in the American Civil War, near the community of Doaksville on June 23, 1865. The Reconstruction Treaties signed at the end of the Civil War fundamentally changed the relationship between the tribes and the U.S. government.

The Reconstruction era played out differently in Indian Territory and for Native Americans than for the rest of the country. In 1862, Congress passed a law that allowed the president, by proclamation, to cancel treaties with Indian Nations siding with the Confederacy (25 USC 72).[18] The United States House Committee on Territories (created in 1825) was examining the effectiveness of the policy of Indian removal, which was after the war considered to be of limited effectiveness. It was decided that a new policy of Assimilation would be implemented. To implement the new policy, the Southern Treaty Commission was created by Congress to write new treaties with the Tribes siding with the Confederacy.

After the Civil War the Southern Treaty Commission re-wrote treaties with tribes that sided with the Confederacy, reducing the territory of the Five Civilized Tribes and providing land to resettle Plains Native Americans and tribes of the mid-west.[19] General components of replacement treaties signed in 1866 include:[20]

- Abolition of slavery

- Amnesty for siding with Confederate States of America

- Agreement to legislation that Congress and the President "may deem necessary for the better administration of justice and the protection of the rights of person and property within the Indian territory."

- That the tribes grant right of way for rail roads authorized by Congress; A land patent, or "first-title deed" to alternate sections of land adjacent to rail roads would be granted to the rail road upon completion of each 20 mile section of track and water stations

- That within each county, a quarter section of land be held in trust for the establishment of seats of justice therein, and also as many quarter-sections as the said legislative councils may deem proper for the permanent endowment of schools

- Provision for each man, woman, and child to receive 160 acres of land as an allotment. (The allotment policy was later codified on a national basis through the passage of The Dawes Act, also called General Allotment Act, or Dawes Severalty Act of 1887)

- That a land patent, or "first-title deed" be issued as evidence of allotment, "issued by the President of the United States, and countersigned by the chief executive officer of the nation in which the land lies"

- That treaties and parts of treaties inconsistent with the replacement treaties to be null and void.

One component of assimilation would be the distribution of property held in-common by the tribe to individual members of the tribe.[21]

The Medicine Lodge Treaty is the overall name given to three treaties signed in Medicine Lodge, Kansas between the U.S. government and southern Plains Indian tribes who would ultimately reside in the western part of Indian Territory (ultimately Oklahoma Territory). The first treaty was signed October 21, 1867, with the Kiowa and Comanche tribes.[22] The second, with the Plains Apache, was signed the same day.[23] The third treaty was signed with the Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho on October 28.[24]

Another component of assimilation was homesteading. The Homestead Act of 1862 was signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln. The Act gave an applicant freehold title to an area called a "homestead" – typically 160 acres (65 hectares or one-fourth section) of undeveloped federal land. Within Indian Territory, as lands were removed from communal tribal ownership, a land patent (or first-title deed) was given to tribal members. The remaining land was sold on a first-come basis, typically by land run, with settlers also receiving a land patent type deed. For these now former Indian lands, the United States General Land Office distributed the sales funds to the various tribal entities, according to previously negotiated terms.

It was in 1866 during treaty negotiations with the federal government on the use of the land, that Choctaw Nation Chief Kiliahote suggested that Indian Territory be given the name Oklahoma, which derives from the Choctaw phrase okla, 'people', and humma, translated as 'red'.[25] He envisioned an all–American Indian state controlled by the tribes and overseen by the United States Superintendent of Indian Affairs. Oklahoma later became the de facto name for Oklahoma Territory, and it was officially approved in 1890, two years after that area was opened to white settlers.[26][27][28]

Oklahoma Territory, end of territories upon statehood

edit| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1890 | 180,182 | — |

| 1900 | 392,060 | +117.6% |

| Source: 1890–1900[29] | ||

The Oklahoma Organic Act of 1890 created an organized Oklahoma Territory of the United States, with the intent of combining the Oklahoma and Indian territories into a single State of Oklahoma. The citizens of Indian Territory tried, in 1905, to gain admission to the union as the State of Sequoyah, but were rebuffed by Congress and an Administration which did not want two new Western states, Sequoyah and Oklahoma. Theodore Roosevelt then proposed a compromise that would join Indian Territory with Oklahoma Territory to form a single state. This resulted in passage of the Oklahoma Enabling Act, which President Roosevelt signed June 16, 1906.[30] empowered the people residing in Indian Territory and Oklahoma Territory to elect delegates to a state constitutional convention and subsequently to be admitted to the union as a single state. Citizens then joined to seek admission of a single state to the Union.

With Oklahoma statehood in November 1907, Indian Territory was effectively extinguished. However, in 2020, the United States Supreme Court prompted a review of tribal lands through its decision in McGirt v. Oklahoma. Subsequently, almost the entire eastern half of Oklahoma was found to have remained Indian country.

Tribes

editTribes indigenous to Oklahoma

editIndian Territory marks the confluence of the Southern Plains and Southeastern Woodlands cultural regions. Its western region is part of the Great Plains, subjected to extended periods of drought and high winds, and the Ozark Plateau is to the east in a humid subtropical climate zone. Tribes indigenous to the present day state of Oklahoma include both agrarian and hunter-gatherer tribes. The arrival of horses with the Spanish in the 16th century ushered in horse culture-era, when tribes could adopt a nomadic lifestyle and follow abundant bison herds.

The Southern Plains villagers, an archaeological culture that flourished from 800 to 1500 AD, lived in semi-sedentary villages throughout the western part of Indian Territory, where they farmed maize and hunted buffalo. They are likely ancestors of the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes. The ancestors of the Wichita have lived in the eastern Great Plains from the Red River north to Nebraska for at least 2,000 years.[31] The early Wichita people were hunters and gatherers who gradually adopted agriculture. By about 900 AD, farming villages began to appear on terraces above the Washita River and South Canadian River in Oklahoma.

Member tribes of the Caddo Confederacy lived in the eastern part of Indian Territory and are ancestors of the Caddo Nation. The Caddo people speak a Caddoan language and is a confederation of several tribes who traditionally inhabited much of what is now East Texas, North Louisiana, and portions of southern Arkansas, and Oklahoma. The tribe was once part of the Caddoan Mississippian culture and thought to be an extension of woodland period peoples who started inhabiting the area around 200 BC. In an 1835 Treaty [32] made at the agency-house in the Caddo Nation and state of Louisiana, the Caddo Nation sold their tribal lands to the U.S. In 1846, the Caddo, along with several other tribes, signed a treaty that made the Caddo a protectorate of the U.S. and established framework of a legal system between the Caddo and the U.S.[33] Tribal headquarters are in Binger, Oklahoma.

The Wichita and Caddo both spoke Caddoan languages, as did the Kichai people, who were also indigenous to what is now Oklahoma and ultimately became part of the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes. The Wichita (and other tribes) signed a treaty of friendship with the U.S. in 1835.[34] The tribe's headquarters are in Anadarko, Oklahoma.

In the 18th century, prior to Indian Removal by the U.S. federal government, the Kiowa, Apache, and Comanche people entered into Indian Territory from the west, and the Quapaw and Osage entered from the east. During Indian Removal of the 19th century, additional tribes received their land either by treaty via land grant from the federal government of the United States or they purchased the land receiving fee simple recorded title.

Tribes from the Southeastern Woodlands

editMany of the tribes forcibly relocated to Indian Territory were from Southeastern United States, including the so-called Five Civilized Tribes or Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee Creeks, and Seminole, but also the Natchez, Yuchi, Alabama, Koasati, and Caddo people.

Between 1814 and 1840, the Five Civilized Tribes had gradually ceded most of their lands in the Southeast section of the US through a series of treaties. The southern part of Indian Country (what eventually became the State of Oklahoma) served as the destination for the policy of Indian removal, a policy pursued intermittently by American presidents early in the 19th century, but aggressively pursued by President Andrew Jackson after the passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830. The Five Civilized Tribes in the South were the most prominent tribes displaced by the policy, a relocation that came to be known as the Trail of Tears during the Choctaw removals starting in 1831. The trail ended in what is now Arkansas and Oklahoma, where there were already many Indians living in the territory, as well as whites and escaped slaves. Other tribes, such as the Delaware, Cheyenne, and Apache were also forced to relocate to the Indian territory.

The Five Civilized Tribes established tribal capitals in the following towns:

- Cherokee Nation – Tahlequah

- Chickasaw Nation – Tishomingo (later moved to Ada)

- Choctaw Nation – Tuskahoma (later moved to Durant)

- Creek Nation – Okmulgee

- Seminole Nation – Wewoka

These tribes founded towns such as Tulsa, Ardmore, Muskogee, which became some of the larger towns in the state. They also brought their African slaves to Oklahoma, which added to the African American population in the state.

- Beginning in 1783, the Choctaw signed a series of treaties with the Americans. The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek was the first removal treaty carried into effect under the Indian Removal Act, ceding land in the future state of Mississippi in exchange for land in the future state of Oklahoma, resulting in the Choctaw Trail of Tears.

- The Muscogee (Creek) Nation began the process of moving to Indian Territory with the 1814 Treaty of Fort Jackson and the 1826 Treaty of Washington. The 1832 Treaty of Cusseta ceded all Creek claims east of the Mississippi River to the United States.

- The 1835 the Treaty of New Echota established terms under which the entire Cherokee Nation was expected to cede its territory in the Southeast and move to Indian Territory. Although the treaty was not approved by the Cherokee National Council, it was ratified by the U.S. Senate and resulted in the Cherokee Trail of Tears.

- The Chickasaw, rather than receiving land grants in exchange for ceding indigenous land rights, received financial compensation. The tribe negotiated a $3 million payment for their native lands, which was not fully funded by the U.S. for 30 years. In 1836, the Chickasaw agreed to purchase land from the previously removed Choctaws for $530,000.[36]

- The Seminole People, originally from the present-day state of Florida, signed the Treaty of Payne's Landing in 1832, in response to the 1830 Indian Removal Act, that forced the tribes to move to Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma. In October 1832, a delegation arrived in Indian Territory and conferred with the Creek Nation tribe that had already been removed to the area. In 1833, an agreement was signed at Fort Gibson (on the Arkansas River just east of Muskogee, Oklahoma), accepting the area in the western part of the Creek Nation. However, the chiefs in Florida did not agree to the agreement. In spite of the disagreement, the treaty was ratified by the U.S. Senate in April 1834.

Tribes from the Great Lakes and Northeastern Woodlands

editThe Western Lakes Confederacy was a loose confederacy of tribes around the Great Lakes region, organized following the American Revolutionary War to resist the expansion of the United States into the Northwest Territory. Members of the confederacy were ultimately removed to the present-day Oklahoma, including the Shawnee, Delaware, also called Lenape, Miami, and Kickapoo.

The area of Pottawatomie County, Oklahoma was used to resettle the Iowa tribe, Sac and Fox, Absentee Shawnee, Potawatomi, and Kickapoo tribes.

The Council of Three Fires is an alliance of the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi tribes. In the Second Treaty of Prairie du Chien in 1829, the tribes of the Council of Three Fires ceded to the United States their lands in Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin. The 1833 Treaty of Chicago forced the members of the Council of Three Fires to move first to present-day Iowa, then Kansas and Nebraska and ultimately to Oklahoma.[37]

The Illinois Potawatomi moved to present-day Nebraska and the Indiana Potawatomi moved to present-day Osawatomie, Kansas, an event known as the Potawatomi Trail of Death. The group settling in Nebraska adapted to the Plains Indian culture but the group settling in Kansas remained steadfast to their woodlands culture. In 1867, part of the Kansas group negotiated the "Treaty of Washington with the Potawatomi" in which the Kansas Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation split and part of their land in Kansas was sold, purchasing land near present-day Shawnee, Oklahoma, they became the Citizen Potawatomi Nation.[38]

The Odawa tribe first purchased lands near Ottawa, Kansas, residing there until 1867 when they sold their lands in Kansas and purchased land in an area administered by the Quapaw Indian Agency in Ottawa County, Oklahoma, becoming the Ottawa Tribe of Oklahoma.

The Peoria tribe, native to Southern Illinois, moved south to Missouri then and Kansas, where they joined the Piankashaw, Kaskaskia, and Wea tribes. Under stipulations of the Omnibus Treaty of 1867, these confederated tribes and the Miami tribe left Kansas for Indian Territory on lands purchased from the Quapaw.[39]

Iroquois Confederacy

editThe Iroquois Confederacy was an alliance of tribes, originally from the Upstate New York area consisting of the Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, Mohawk, and, later, Tuscarora. In the pre-Revolutionary War era, their confederacy expanded to areas from Kentucky and Virginia north. All of the members of the Confederacy, except the Oneida and Tuscarora, allied with the British during the Revolutionary War, and were forced to cede their land after the war. Most moved to Canada after the Treaty of Canandaigua in 1794, though some remained in New York state and some moved to Ohio, where they joined the Shawnee.

The 1838 and 1842 Treaties of Buffalo Creek were treaties with New York Indians, such as the Seneca, Mohawk, Cayuga, and Oneida Indian Nation, which covered land sales of tribal reservations under the U.S. Indian removal program, under which they planned to move most eastern tribes to Indian Territory. Initially, the tribes were moved to the present state of Kansas, and later to Oklahoma on land administered by the Quapaw Indian Agency.

Plains Indian tribes

editWestern Indian Territory is part of the Southern Plains and is the ancestral home of the Wichita people, a Plains tribe. Additional indigenous peoples of the Plains entered Indian Territory during the horse culture era. Prior to adoption of the horse, some Plains Indian tribes were agrarian and others were hunter-gatherers. Some tribes used the dog as a draft animal to pull small travois (or sleighs) to help move from place to place; however, by the 18th century, many Southern Plains tribes adopted the horse culture and became nomadic. The tipi, an animal hide lodge, was used by Plains Indians as a dwelling because they were portable and could be reconstructed quickly when the tribe settled in a new area for hunting or ceremonies.

The Arapaho historically had assisted the Cheyenne and Lakota people in driving the Kiowa and Comanche south from the Northern Plains, their hunting area ranged from Montana to Texas. Kiowa and Comanche controlled a vast expanse of territory from the Arkansas River to the Brazos River. By 1840 many plains tribes had made peace with each other and developed Plains Indian Sign Language as a means of communicate with their allies.

- The Kaw speak one of the Siouan languages and were originally from the Kansas area; the name Kansas is derived from the tribe's name. The Kaw are closely related to the Osage Nation and Ponca tribes, who first settled in Nebraska, being from the same tribe before migrating from the Ohio valley in the mid-17th century. On June 4, 1873, the Kaw removed themselves from Kansas to an area that would become Kay County, Oklahoma, tribal headquarters is in Kaw City, Oklahoma.

- The Ponca speak one of the Siouan languages and are closely related to the Osage Nation and Kaw tribes. The Ponca tribe were never at war with the U.S. and signed the first peace treaty in 1817.[40] In 1858 the Ponca signed a treaty, ceding part of their land to the United States in return for annuities, payment of $1.25 per acre from settlers, protection from hostile tribes and a permanent reservation home on the Niobrara River at the confluence with the Missouri River.[41] In the 1868 U.S.-Sioux Treaty of Fort Laramie[42] the US mistakenly included Ponca lands in present-day Nebraska in the Great Sioux Reservation of present-day South Dakota. Conflict between the Ponca and the Sioux/Lakota, who now claimed the land as their own by U.S. law, forced the U.S. to remove the Ponca from their own ancestral lands to Indian Territory in 1877, parts of the current Kay and Noble counties in Oklahoma. The land proved to be less than desirable for agriculture and many of the tribe moved back to Nebraska. In 1881, the US returned 26,236 acres (106.17 km2) of Knox County, Nebraska, to the Ponca, and about half the tribe moved back north from Indian Territory. Today, the Ponca Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma have their headquarters in Ponca City, Oklahoma.

- The Otoe-Missouria Tribe of Indians, speak one of the Siouan languages and split away from the Ho-Chunk in Wisconsin prior to European contact. The tribe is made up of Otoe and Missouria Indians, is located in part of Noble County, Oklahoma with tribal offices in Red Rock, Oklahoma. Both tribes originated in the Great Lakes region by the 16th century had settled near the Missouri and Grand Rivers in Missouri.[43]

- The Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma are a united tribe of the Southern Arapaho and the Southern Cheyenne people, headquartered in Concho, Oklahoma (a rural suburb of Oklahoma City.)

- The Cheyenne were originally an agrarian people in present-day Minnesota and speak an Algonquian language. In 1877, after the Battle of the Little Bighorn in present-day Montana, a group of Cheyenne were escorted to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). However, they were not used to the dry heat climate and food was insufficient and of poor quality. A group of Cheyenne left the territory without permission to travel back north. Ultimately, the military gave up attempting to relocate the Northern Cheyenne back to Oklahoma and a Northern Cheyenne reservation was established in Montana

- The Arapaho came from the present-day Saskatchewan, Montana, and Wyoming area, and speak an Algonquian language.

- The Comanche lived in the upper Platte River in Wyoming breaking off from the Shoshone people in the late 17th century, and speak a Numic language of the Uto-Aztecan family. A nomadic people, the Comanche never developed the political idea of forming a single nation or tribe instead existing as multiple autonomous bands. The Comanche (and other tribes) signed a treaty of friendship with the U.S. in 1835.[34] An additional treaty was signed in 1846.[33] In 1875, the last free band of Comanches, led by Quanah Parker, surrendered and moved to the Fort Sill reservation in Oklahoma. The Comanche Nation is headquartered in Lawton, Oklahoma.

- The Pawnee speak a Caddoan language. Originally from the area around Omaha, Nebraska. In the 16th century Francisco Vásquez de Coronado had an encounter with a Pawnee chief. In the 1830s exposure to infectious diseases, such as measles, smallpox and cholera decimated the tribe. The 1857 Treaty with the Pawnee,[44] their range was reduced to an area around Nance County, Nebraska. In 1874 the tribe was relocated to land in the Cherokee Outlet in Oklahoma Territory, in Pawnee County, Oklahoma. Tribal Headquarters are in Pawnee, Oklahoma.

- The Tonkawa speak a language isolate, that is a language with no known related languages. The Tonkawa seem to have inhabited northeastern Oklahoma in the 15th century. However, by the 18th century the Plains Apache had pushed the Tonkawa south to what is now southern Texas. After Texas was admitted as a State, the Tonkawa signed the 1846 Treaty with the Comanche and other Tribes at Council Springs, Texas.[33] After siding with the Confederacy, acting as scouts for the Texas Rangers, the Tonkawa Massacre, occurring near Lawton, Oklahoma, killed about half of the tribe. In 1891 the Tonkawa were offered allotments in the Cherokee Outlet near present-day Tonkawa, Oklahoma.

- The Kiowa originated in the area of Glacier National Park, Montana and speak a Kiowa-Tanoan language. In the 18th century the Kiowa and Plains Apache moved to the plains adjacent to the Arkansas River in Colorado and Kansas and the Red River of the Texas Panhandle and Oklahoma. In 1837 the Kiowa (and other tribes) signed a treaty of friendship with the U.S. that established a framework for legal system administered by the US. Provided for trade between Republics of Mexico and Texas.[45] Tribal headquarters are in Carnegie, Oklahoma

- The Plains Apache or "Kiowa Apache", a branch of the Apache that lived in the upper Missouri River area and speak one of the Southern Athabaskan languages. In the 18th century, the branch migrated south and adopted the lifestyle of the Kiowa. Tribal headquarters are in Anadarko, Oklahoma.

- The Osage Nation speak one of the Siouan languages and originated in present-day Kentucky. As the Iroquois moved south, the Osage moved west. By the early 18th century the Osage had become the dominant power in the Oklahoma, Arkansas, Missouri and Kansas, controlling much of the land between the Red River and Missouri River. From 1818 to 1825 a series of treaties reduced the Osage lands to Independence, Kansas. With the 1870 Drum Creek Treaty, the Kansas land was sold for $1.25 per acre and the Osage purchased 1,470,000 acres (5,900 km2) in Indian Territory's Cherokee Outlet, the current Osage County, Oklahoma. While the Osage did not escape the federal policy of allotting communal tribal land to individual tribal members, they negotiated to retain communal mineral rights to the reservation lands. These were later found to have crude oil, from which tribal members benefited from royalty revenues from oil development and production. Tribal headquarters are in Pawhuska, Oklahoma.

Plateau tribes

editAfter the Modoc War from 1872 to 1873, Modoc people were forced from their homelands in southern Oregon and northern California to settle at the Quapaw Agency, Indian Territory. The federal government permitted some to return to Oregon in 1909. Those that remained in Oklahoma became the Modoc Tribe of Oklahoma.[46]

The Nez Perce, a Plateau tribe from Washington and Idaho, were sent to Indian Territory as prisoners of war in 1878, but after great losses in their numbers due to disease, drought and famine, they returned to their northwestern homelands in 1885.[47]

Government

editDuring the Reconstruction Era, when the size of Indian Territory was reduced, the renegotiated treaties with the Five Civilized Tribes and the tribes occupying the land of the Quapaw Indian Agency contained provisions for a government structure in Indian Territory. Replacement treaties signed in 1866 contained provisions for:[20]

- Indian Territory Legislature would have proportional representation from tribes over 500 members

- Laws take effect unless suspended by Secretary of the Interior or President of the United States

- No laws shall be inconsistent with the United States Constitution, or laws of Congress, or treaties of the United States

- No legislation regarding "matters pertaining to the legislative, judicial, or other organization, laws, or customs of the several tribes or nations, except as herein provided for"

- Superintendent of Indian Affairs (or appointee) is the presiding officer of the Indian Territory Legislature

- Secretary of Interior appoints secretary of the Indian Territory Legislature

- A court or courts may be established in Indian Territory with such jurisdiction and organization as Congress may prescribe: "Provided that the same shall not interfere with the local judiciary of either of said nations."

- No session in any one year shall exceed the term of thirty days, and provided that the special sessions may be called whenever, in the judgment of the Secretary of the Interior, the interests of said tribes shall require it

In a continuation of the new policy, the 1890 Oklahoma Organic Act extended civil and criminal laws of Arkansas over the Indian Territory,[48] and extended the laws of Nebraska over Oklahoma Territory.[49]

See also

edit- Historic regions of the United States

- Missouri Compromise

- Territorial evolution of the United States

- Territories of Spain that encompassed land that would later become part of Indian Territory:

- U.S. territories that encompassed land that would later become part of Indian Territory:

- District of Louisiana, 1804–1805

- Territory of Louisiana, 1805–1812

- List of federally recognized tribes by state and List of federally recognized tribes alphabetic

- Treaties

- Treaty of Fort Clark with the Osage.

- Osage Treaty (1825)

- Cherokee Commission

- Northwest Indian War the battle for Ohio

- Former Indian Reservations in Oklahoma

- Indian country jurisdiction

References

edit- ^ Everett, Dianna. "Indian Territory Archived 2012-02-25 at the Wayback Machine," Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, published by the Oklahoma Historical Society (accessed October 17, 2013).

- ^ Pennington, William D. Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. "Reconstruction Treaties." Retrieved February 16, 2012.[1] Archived 2014-02-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Acquisition of the Public Domain, 1781–1867, Table 1.1" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 23, 2011. Retrieved 2012-03-02.

- ^ a b "Downes v. Bidwell, 182 U.S. 244 (1901)". Retrieved 2012-03-02.

- ^ "Encyclopedia of Arkansas". Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Retrieved 2020-07-09.

- ^ Stein, Mark, 1951- (2008). How the States got Their Shapes (First ed.). New York. ISBN 978-0-06-143138-8. OCLC 137324984.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Everett, Dianna. Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. "Indian Territory."". Archived from the original on 2012-02-25. Retrieved 2012-02-15.

- ^ "Subchapter I – Treaties". 25 USC Chapter 3 – Agreements with Indians. uscode – house.gov. Archived from the original on March 17, 2012. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ^ 25 U.S.C. § 71. Indian Appropriation Act of March 3, 1871, 16 Stat. 544, 566

- ^ Congress' plenary authority to "override treaty provisions and legislate for the protection of the Native Americans." United States v. City of McAlester, 604 F.2d 42, 47 (10th Cir. 1979)

- ^ United States v. Blackfeet Tribe of Blackfeet Indian Reservation, 364 F.Supp. 192, 194 (D.Mont. 1973) ("[A]n Indian tribe is sovereign to the extent that the United States permits it to be sovereign – neither more nor less.")

- ^ "United States v. Kagama, 118 U.S. 375 (1886), Filed May 10, 1886". Retrieved 2012-04-29.

- ^ "United States v. Kagama – 118 U.S. 375 (1886)". Retrieved 2012-04-29.

- ^ Huston, James L. "The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture: Civil War Era". Oklahoma Historical Society. Retrieved June 20, 2024.

- ^ Gibson, Arrell (1981), Oklahoma, a History of Five Centuries, University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 0-8061-1758-3

- ^ Debo, Angie (1934). "The Civil War and Reconstruction". The Rise and Fall of the Choctaw Republic. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 80.

- ^ "Act of Congress, R.S. Sec. 2080 derived from act July 5, 1862, ch. 135, Sec. 1, 12 Stat. 528". Archived from the original on March 17, 2012. Retrieved 2012-02-07.

- ^ "Abrogation of treaties (25 USC Sec. 72) Codification R.S. Sec. 2080 derived from act July 5, 1862, ch. 135, Sec. 1, 12 Stat. 528". Archived from the original on March 17, 2012. Retrieved 2012-02-07.

- ^ Pennington, William D. Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. "Reconstruction Treaties." Retrieved February 16, 2012. [2] Archived 2014-02-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Treaty of Washington United States–Choctaw Nation–Chickasaw Nation, 14 Stat. 769, signed April 28, 1866". Archived from the original on February 16, 2012. Retrieved March 3, 2012.

- ^ Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek: Hearings on H.R. 19213 Before the H. Subcomm. on Indian Affairs, at 24 (February 14, 1912) (statement of Hon. Byron P. Harrison) ("While the {1866 Treaty of Washington} contemplated the immediate allotment in severalty of the lands in the Choctaw-Chickasaw country, yet such allotment in severalty to anyone was never made under such treaty, and has only been consummated since the breaking up of the tribal organization and preparatory to the organization of the State of Oklahoma.")

- ^ "Treaty with the Kiowa and Comanche, 1867 (15 Stats., 581) (Medicine Lodge Treaty #1)". Archived from the original on 2011-11-26.

- ^ "Treaty with the Kiowa, Comanche, and Apache, 1867" (Medicine Lodge Treaty #2), (15 Stats. 589)". Archived from the original on 2017-05-30. Retrieved 2012-02-29.

- ^ "Treaty with the Cheyenne and Arapaho, 1867" (Medicine Lodge Treaty #3), (15 Stats. 593)". Archived from the original on 2009-06-29. Retrieved 2012-02-29.

- ^ "Choctaw Dictionary » Search Results » humma". Retrieved 2021-10-12.

- ^ Wright, Muriel (June 1936). "Chronicles of Oklahoma". Oklahoma State University. Archived from the original on October 13, 2007. Retrieved July 31, 2007.

- ^ "Oklahoma State History and Information". A Look at Oklahoma. Oklahoma Department of Tourism and Recreation. 2007. Archived from the original on July 29, 2006. Retrieved June 7, 2006.

- ^ Merserve, John (1941). "Chief Allen Wright". Chronicles of Oklahoma. Archived from the original on May 7, 2006. Retrieved June 7, 2006.

- ^ Forstall, Richard L. (ed.). Population of the States and Counties of the United States: 1790–1990 (PDF) (Report). United States Census Bureau. p. 132. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- ^ "Enabling Act (Oklahoma) Public Law 234, HR 12797, Jun 16, 1906 (59th Congress, Session 1, chapter 3335". Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved 2012-01-30.

- ^ Schlesier, Karl H. Plains Indians, 500–1500 AD: The Archaeological Past of Historic Groups. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1994: 347–348.

- ^ "Treaty with the Caddo, July 1, 1835 (7 Stat., 470)". Archived from the original on 2012-02-17. Retrieved 2012-03-01.

- ^ a b c "Treaty with the Comanche, Aionai, Anadarko, Caddo, etc., Wacoes, Keeches, Tonkaways, Wichetas, Towa-KarroesMay 15, 1846, (9 Stat., 844). The treaty established the US as a protectorate of the tribes and established legal procedures between tribes and the U.S., Signed at Council Springs, Texas". Archived from the original on June 15, 2010. Retrieved 2012-03-01.

- ^ a b "Treaty with the Comanche, Etc., Aug. 24, 1835. (7 Stat., 474) Treaty of Friendship between U.S. and Comanche and Witchetaw nations, and Cherokee Muscogee, Choctaw, Osage, Seneca and Quapaw and established framework for legal system supervised by U.S. Signed on the eastern border of the Grand Prairie, near the Canadian river, in the Muscogee nation". Archived from the original on 2012-02-15. Retrieved 2012-03-02.

- ^ Moser, George W. A Brief History of Cherokee Lodge #10 (retrieved 26 June 2009).

- ^ Burt, Jesse; Ferguson, Bob (1973). "The Removal". Indians of the Southeast: Then and Now. Nashville and New York: Abingdon Press. pp. 170–173. ISBN 978-0-687-18793-5.

- ^ "1833 Treaty with the Chippewa, etc". Retrieved 2012-02-29.

- ^ "Treaty of Washington with the Potawatomi 1867". Archived from the original on 2012-03-24. Retrieved 2012-02-29.

- ^ Roberson, Glen (2009). "Peoria". The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ^ "1817 Ponca Treaty with the U.S." Archived from the original on 2012-01-14. Retrieved 2012-03-01.

- ^ "1858 Ponca Treaty with the U.S." Archived from the original on 2015-02-13. Retrieved 2012-03-01.

- ^ "US-Sioux Treaty of 1868". Archived from the original on 2011-11-26. Retrieved 2011-11-04.

- ^ "May, John D. Otoe-Missouria. Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture". Archived from the original on 2010-07-20. Retrieved 2012-03-01.

- ^ "1957 Treaty with the Pawnee". Archived from the original on 2012-02-16. Retrieved 2012-03-01.

- ^ "Treaty with the Kiowa, Etc., May 26, 1837 (7 Stat. 533). Treaty of friendship between U.S. and Kioway, Ka-ta-ka, and Ta-wa-ka-ro nations and Comanche, Witchetaw, Cherokee Muscogee, Choctaw, Osage, Seneca and Quapaw nations or tribes of Indians and provided for trade between Republics of Texas and Mexico, signed at Fort Gibson, Oklahoma". Archived from the original on May 30, 2017. Retrieved 2012-03-02.

- ^ Self, Burl E. "Modoc". Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Oklahoma Historical Society. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ Westmoreland, Ingrid. "Nez Perce". Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ 26 Stat. 81, at 94-97

- ^ "Organic Act, 1890, Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History". Archived from the original on 2011-07-26. Retrieved 2012-01-30.

Further reading

edit- Clampitt, Bradley R. The Civil War and Reconstruction in Indian Territory (University of Nebraska Press, 2015). viii, 192 pp. [ISBN missing]

- Confer, Clarissa W. The Cherokee Nation in the Civil War (University of Oklahoma Press, 2007) [ISBN missing]

- Gibson, Arrell Morgan. "Native Americans and the Civil War," American Indian Quarterly (1985), 9#4, pp. 385–410 JSTOR 1183560

- Minges, Patrick. Slavery in the Cherokee Nation: The Keetowah Society and the Defining of a People, 1855–1867 (Routledge, 2003) [ISBN missing]

- Reese, Linda Williams. Trail Sisters: Freedwomen in Indian Territory, 1850–1890 (Texas Tech University Press; 2013), 186 pages; Studies black women held as slaves by the Cherokee, Choctaw, and other Indians [ISBN missing]

- Smith, Troy. "The Civil War Comes to Indian Territory", Civil War History (September 2013), 59#3, pp. 279–319 online

- Wickett, Murray R. Contested Territory: Whites, Native Americans and African Americans in Oklahoma, 1865–1907 (Louisiana State University Press, 2000) [ISBN missing]

Primary sources

edit- Edwards, Whit. "The Prairie Was on Fire": Eyewitness Accounts of the Civil War in the Indian Territory (Oklahoma Historical Society, 2001) [ISBN missing]

External links

edit- Twin Territories: Oklahoma Territory – Indian Territory

- Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture – Indian Territory

- High resolution maps and other items at the National Archives

- See 1890s photographs of Native Americans in Oklahoma Indian Territory hosted by the Portal to Texas History

- Treaties by Tribe Name, Vol. II (Treaties) in part. Compiled and edited by Charles J. Kappler. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1904

- Oklahoma Digital Maps Collection

- Hawes, J. W. (1879). . The American Cyclopædia.

- Peters, Gerhard; Woolley, John T (February 10, 1890). "Benjamin Harrison: 'Proclamation 295 – Sioux Nation of Indians'". The American Presidency Project. University of California – Santa Barbara. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- Peters, Gerhard; Woolley, John T. "Benjamin Harrison: "Proclamation 298 – Extinguishing Indian Title to Certain Lands," October 23, 1890". The American Presidency Project. University of California – Santa Barbara. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2016.