°

Orang Indonesia Perantauan | |

|---|---|

| |

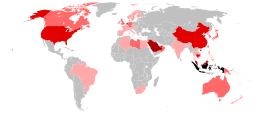

Map of the Indonesian diaspora around the world | |

| Total population | |

| Total: 6-9 million[Note 1] 2023 estimate[1][2][3] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| |

| |

| |

| 300,000 (assimilate into the local Cape Malays)[22][23] | |

| 300,000 (2020)[24] | |

| 200,000 (2019)[25] | |

| 145,031 (2022)[26][27][28] | |

| 122,028 (2023)[29] | |

| 111,987 (2019)[30] | |

| c. 87,000–92,400 (2021) (Indonesian-born)[31][32] | |

| |

| 100,000 (2024)[35] | |

| 80,000 (2018)[36] (excluding Indonesian ancestry) | |

| 46,586 (2019)[30] | |

| 43,871[37][38] | |

| 42,000 (2019)[39] | |

| 40,148 (2014) (assimilate into the local Sri Lankan Malays) | |

| 38,000 (2020)[40] (only Indonesian legal workers) | |

| 37,669 (2019)[30] | |

| 33,000[41] | |

| 28,954 (2020)[30] | |

| 24,000 (2021)[42] | |

| 21,390 (2016)[43] | |

| 12,904 (2019)[30] | |

| 11,000[41] | |

| 7,310 (2022)[44] | |

| 7,000[41] | |

| 6,000[41] | |

| 4,300 | |

| 3,000-5,000 (See: Overseas Acehnese)[41] | |

| 4,000[41] | |

| 3,000 | |

| 2,400 (2020)[45] | |

| 2,000[41] | |

| Languages | |

| Indonesian, Regional Languages of Indonesia, English, Dutch, Chinese, Arabic, Afrikaans, German, Japanese, Tagalog, Korean, Papiamento, Cantonese, Taiwanese | |

| Religion | |

| Islam · Christianity · Hinduism · Buddhism · Confucianism · Irreligion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Native Indonesians, Dutch Indonesians, Arab Indonesians, Chinese Indonesians | |

Overseas Indonesians (Indonesian: Orang Indonesia Perantauan) are Indonesians who live outside of Indonesia. These include citizens that have migrated to another country as well as people born abroad of Indonesian descent. According to Ministry of Law and Human Rights, more than 6-9 million Indonesians diaspora live abroad in 2023.[Note 4]

History

editSince ancient times, people from various ethnic groups of Indonesia have been leaving their hometowns to other parts of the world for purposes of trade, education, labor, or travel. Migration of ancient Indonesians began 2,000 years ago, they migrated to various places including Madagascar, East Africa, the Middle East, the Indian subcontinent, Australia, and Southeast Asian countries.

Early history

editBeginning between the 5th and 7th centuries, Austronesian seafarers from the Indonesian archipelago, particularly from Kalimantan and Sulawesi, embarked on a remarkable journey across the Indian Ocean to Madagascar. These early migrants established settlements, bringing with them advanced agricultural techniques, including the cultivation of rice and bananas, as well as their language and cultural practices. The influence of these early Indonesians is evident in the Malagasy language, which retains many Austronesian elements, and in the genetic makeup of the Malagasy people, who exhibit a blend of Southeast Asian and African ancestries.

During the era of the Srivijaya Empire (7th - 13th centuries), centered in Sumatra, Indonesian traders and settlers expanded their influence throughout Southeast Asia. The Srivijaya Empire was a powerful maritime kingdom that controlled key trade routes, facilitating the movement of people and goods. Indonesian traders established communities in the Malay Peninsula, Thailand, and the Philippines, spreading their cultural and religious practices, including Buddhism and Hinduism. This period of maritime dominance laid the groundwork for further cultural and economic exchanges in the region.

The subsequent Majapahit Empire (13th - 16th centuries), based in Java, continued to expand Indonesian influence through its extensive trade networks. The Majapahit Empire was known for its powerful navy and commercial prowess, which allowed it to control trade routes and exert influence over much of Southeast Asia. Indonesian traders and settlers played a crucial role in the exchange of goods, ideas, and technologies, further integrating the region and spreading Indonesian cultural and religious practices.

During the colonial era

editThe Dutch colonial period (16th - 20th centuries) marked a significant shift in Indonesian migration patterns. Under the control of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), which wielded authority over vast swathes of the Indonesian archipelago, Indonesians were forcibly relocated as laborers to other parts of the Dutch Empire. This included destinations such as Suriname, Malaysia, Singapore, and Sri Lanka. Additionally, during the 18th century, political dissidents opposing Dutch colonization were deported from Indonesia to South Africa, where they formed a community known as the Cape Malays.[48]

Merantau culture

editThe practice of going abroad has been motivated by the Merantau culture of the Indonesian people since ancient times. Merantau has been associated deeply with the Minangkabau people as a cultural way of life. A Minangkabau man at the time of young adulthood (20–30 years old) is often encouraged to go abroad as part of the Minangkabau culture; this serves as a sign of manhood to accrue wealth, knowledge, and life experience.[49] This practice can be traced to the 7th century, when Minangkabau merchants played a major role in establishing of the Malay kingdom in Jambi, which was a strategic position for trade via the Silk Road.

Other Indonesian ethnic groups such as the Bugis, Banjar, Madura, Aceh, Batak, and Javanese have also been traveling overseas to gain opportunities, experience, knowledge, and versatility.

Indonesians worldwide

editAustralia

editBefore Dutch and British sailors arrived in Australia, Indonesians from Southern Sulawesi have explored the Australia northern coast. Each year, the Bugis sailors would sail down on the northwestern monsoon in their wooden pinisi. They would stay in Australia for several months to trade and take tripang (or dried sea cucumber) before returning to Makassar on the dry season off shore winds. These trading voyages continued until 1907.[citation needed] Nowadays, many Indonesian residents of Australia are either foreign students or workers, with a large number being of Chinese Indonesian heritage. Furthermore, the Cocos Malays are descendants of native Indonesians brought by the Clunies-Ross family to work in the copra industry in the 19th century.

Cambodia

editAccording Interior Ministry of Cambodia, more than 100,000 Indonesian citizen lived in Cambodia.[35]

Hong Kong

editIndonesians are the second largest foreigner group after Filipinos, mainly working as female domestic helpers from Java Island. There are also several Chinese Indonesian families and students that reside in Hong Kong. Central and Wan Chai are the main districts that most Indonesians live in.

Japan

editIn 2013, approximately 20,000 Indonesians lived in Japan, including about 3,000 illegal Indonesians. These numbers dropped from the previous years for various reasons, including the high cost of living in Japan and the difficulty of finding jobs in Japan. Most of them are in Japan for a short term and deportation remains high for Indonesian residents. In 2022, approximately 98,865 Indonesians lived in Japan.[50]

Malaysia

editMalaysia shares a land border with Indonesia and both countries share many aspects of their culture, including mutually intelligible national languages. Populations have long moved between the areas which make up the modern-day states. Since the distinction between the two regions emerged in the early 19th century, many people from Java, Kalimantan, Sumatra, and Sulawesi, which are located in modern-day Indonesia, migrated and settled in the Malay Peninsula and in Malaysian Borneo. These earlier populations have mostly effectively or partially assimilated with the larger Malaysian-Malay community due to religious, social and cultural similarities. Currently, it is also estimated that there are around 2 million Indonesian citizens in Malaysia at any given time, ranging from all types of backgrounds including a significant majority of labour migrants alongside a considerable number of professionals and students.

Netherlands

editIndonesia was a colony of the Netherlands from 1605 until 1949. During and after the Indonesian National Revolution, many Moluccans and Indo people, people of mixed Dutch and Indonesian ancestry migrated to the Netherlands. Most of them were former members of the KNIL army. In this way, around 360,000 Indo people and Totoks (white people) and 12,500 persons from Maluke ancestry were settled in the Netherlands. Giovanni van Bronckhorst, Denny Landzaat, Roy Makaay, Mia Audina, and Daniel Sahuleka are notable people of Indonesian ancestry from the Netherlands. These 372,500 first generation people and their 2nd, 3rd and 4th generation offspring account for some 1.6 million Dutch passport-holders and form as much as 10% of the overall population of the Netherlands.

Tong Tong Fair is the largest cultural festival in the world for Indonesian diaspora. Established in 1959, it is one of the oldest festivals and the fourth largest grand fair in the Netherlands. It is also the annual event with the highest number of paying visitors of the Dutch city of The Hague, having consistently attracted more than 100,000 visitors since 1993.

The Netherlands is also one of the European countries with most Indonesian students. In the early 20th century, many Indonesian students studied in the Netherlands. Most of them lived in Leiden and were active in the Perhimpoenan Indonesia (Indonesian Association). There were 1.402 Indonesian nationals enrolled in Dutch universities in 2018/2019, which makes it the 13th largest student communities in the country.[51]

Philippines

editThe official number of Indonesians in the Philippines range anywhere from 43,871 to 101,720.[37] They reside mostly in the island of Mindanao, in the Muslim parts with a noticeable community in Davao City that has an international school for the overseas community. They tend to be protective of their separate ethnic identity. Most are Muslims, while many others are also Christian, coming from Minahasan-speaking ancestry.

Qatar

editThere are about 39,000 Indonesian citizens in the State of Qatar according to the Indonesian Embassy.[52]

Saudi Arabia

editIndonesian pilgrims have long lived in Hejaz, a region along the west coast of Saudi Arabia. Among them was Shaykh Ahmad Khatib Al-Minangkabawi who was from Minangkabau origin in Sumatra. He served as the Imam and taught at the Shafi'i school at the Grand Mosque in Mecca during the late 19th century.[53]

Many Indonesians in Saudi Arabia are domestic workers, with a minority of other types of labour migrants and students. Most of the santris (Islamic boarding school pupils) from Indonesia also have continued to pursue their education in Saudi, such as in the Islamic University of Madinah and the Umm al-Qura University in Mecca. A number of Indonesian expatriates in Saudi Arabia work in diplomatic sectors and local private and foreign companies, such as in the Saudi Aramco, banking companies, Saudia Airlines, SABIC, Schlumberger, Halliburton, Indomie, etc. Most Indonesians in Saudi Arabia reside in Riyadh, Jeddah, and all around the Dammam area.

Saudis of Indonesian descent

editThere are Saudi citizens who reside in Mecca and Jeddah that are of Indonesian descent. Their forefathers came from Indonesia by sea during the late 19th century til the mid 20th century for pilgrimage, trade, and Islamic education purposes. Many of them did not return to their homeland thus they decided to stay in Saudi and their descendants have become Saudi citizens ever since. Many of them also married with local Arab women and stayed permanently in Saudi. Their descendants today are recognizable with their family name originating from their forefathers' origins back in Indonesia, such as "Bugis", "Banjar", "Batawi" (Betawi), "Al-Felemban" (Palembang), "Faden" (Padang), "Al-Bantani" (Banten), "Al-Minangkabawi" (Minangkabau), "Bawayan" (Bawean), and many more. One of them is Muhammad Saleh Benten, a Saudi politician appointed by King Salman as the Minister of Hajj and Umrah.[54]

Singapore

editThe Malays in Singapore (Malay: Orang Melayu Singapura) make up about 14% of the country's population. Most of them came from what we know today as Indonesia and southern Malaysia. In the 19th century, Singapore was part of Johor-Riau Sultanate. Many Indonesian people, mainly Bugis and Minangkabau settled in Singapore. From 1886 till 1890, as many as 21,000 Javanese became bonded labourers with the Singapore Chinese Protectorate, an organisation formed by the British in 1877 to monitor the Chinese population. They performed manual labour in the rubber plantations. After their bond ended, they continued to open up the land and stayed on in Johore. Famous Singaporeans of Indonesian descent are the first president of Singapore Yusof bin Ishak, and Zubir Said who composed the national anthem of Singapore Majulah Singapura.

According to the Indonesian Embassy in Singapore, as of 2010 there are 180,000 Indonesian citizens in Singapore. As much as 80,000 work as domestic helpers/TKI, 10,000 as sailors, and the rest are either students or professionals. But the number can be higher as registering one's residence is not compulsory for Indonesians, putting the number to around 200,000 people.

South Africa

editSouth Korea

editSuriname

editPeople of Indonesian descent, mainly Javanese, make up 15% of the population of Suriname. In the 19th century, the Dutch sent the Javanese to Suriname as indentured laborers in plantations. The most famous person of Indonesian descent is Paul Somohardjo as the speaker of the National Assembly of Suriname.[55]

Taiwan

editUnited Arab Emirates

editUnited Kingdom

editUnited States

editThe United States is home to many Indonesian students and professionals. In the Silicon Valley region of Northern California, there are many professional Indonesian-American engineers in the technology industry who are employed in companies like Cisco Systems, KLA Tencor, Google, Yahoo, Sun Microsystems, and IBM. Sehat Sutardja, the CEO of Marvell Technology Group, is a prominent Indonesian professional in the USA.[56]

In April 2011, the Special English service of Voice of America reported on a push for American universities to attract more Indonesians to study in America in order to compete with students' preferred universities in Australia, Singapore, and Malaysia.[57]

List of Indonesian diaspora by ethnicity and culture

editSee also

editNotes

edit- ^ Indonesian citizens, ex-Indonesian citizens, foreign citizens who are children of Indonesian citizens, and children of ex-Indonesian citizens, illegal and undocumented workers. However, it does not include Indonesian descendants. According to the Director of Indonesian Citizen Protection, from that number 2,276,722 people are Indonesian citizens. Although it is estimated that there are still millions of Indonesian citizens who have not been recorded.

- ^ including illegal workers

- ^ Indonesian citizen registered in KBRI (Embassy of Indonesia in Saudi Arabia)

- ^ this include ex-Indonesian citizens, foreign citizens who are children of Indonesian citizens, and children of ex-Indonesian citizens, illegal and undocumented workers. However, it does not include Indonesian descendants.[46] According to the Director of Indonesian Citizen Protection, from that number 2,276,722 people are Indonesian citizens. Although it is estimated that there are still millions of Indonesian citizens who have not been recorded.[47]

References

edit- ^ "Jokowi Minta Menkumham Kaji Status Kewarganegaraan" (in Indonesian).

- ^ "Imigrasi Terbitkan Visa Diaspora Untuk Dukung Ekonomi" (in Indonesian).

- ^ "Kemlu: 2,2 Juta WNI Tinggal di Luar Negeri" (in Indonesian).

- ^ "Pribumi". Encyclopedia of Modern Asia. Macmillan Reference USA. Archived from the original on 11 July 2007. Retrieved 2006-10-05.

- ^ "Malaysia, Negeri Perantau Indonesia" (in Indonesian). September 2009.

- ^ Wahyu Dwi Anggoro (20 August 2013). "Mayoritas Melayu Malaysia Keturunan Indonesia". Okezone (in Indonesian).

- ^ "Migrasi dan Perkawinan Politik Menghubungkan Melayu dan Nusantara" (in Indonesian).

- ^ "History of Javanese Migration to Malaysia" (in Indonesian). Kompas. 5 August 2022. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- ^ "The Javanese connection in Malaysia". MalaysiaKini. 21 November 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- ^ Purnomo, Indra. "Tersebar di Berbagai Negara, Pekerja Migran asal RI Capai 9 Juta Orang". idxchannel.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2022-02-26.

- ^ "5,3 Juta PMI Ilegal Diperkirakan Bekerja di Malaysia hingga Timur Tengah". merdeka.com (in Indonesian). 2021-05-14. Retrieved 2022-02-24.

- ^ "Diaspora Indonesia di Belanda Semangat "Bangun Negeri via Investasi"". Kementerian Luar Negeri Repulik Indonesia (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2022-02-24.

- ^ "PM Rutte: 1 dari 10 Orang Belanda Berasal dari Indonesia" (in Indonesian).

- ^ "CBS Statline". opendata.cbs.nl (in Dutch). 31 May 2022. Retrieved 2024-03-10.

- ^ "Migratie uit Indonesië en Indonesische inwoners in Nederland" (in Dutch). Retrieved 2023-12-31.

- ^ "Mantan Dubes RI: 50 Persen Penduduk Makkah Keturunan Indonesia". 28 March 2016.

- ^ "4 Tokoh Arab Saudi Keturunan Indonesia, Terakhir Jadi Saksi Kemerdekaan RI".

- ^ "Negara yang Banyak Orang Jawa, Nomor 1 Jumlahnya Lebih dari 1,5 Juta Jiwa".

- ^ "Data Agregat WNI yang Tercatat di Perwakilan RI" (PDF). 25 July 2024.

- ^ Milner, Anthony (2011). "Chapter 7, Multiple forms of 'Malayness'". The Malays. John Wiley & Sons. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-7748-1333-4. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ^ "Pemerintah Dorong Diaspora Indonesia Turut Aktif Membangun Negeri". setneg.go.id (in Indonesian).

- ^ Vahed, Goolam (13 April 2016). "The Cape Malay:The Quest for 'Malay' Identity in Apartheid South Africa". South African History Online. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ^ "Malay, Cape in South Africa". Retrieved 2022-03-21.

- ^ "KDEI Taipei - Kantor Dagang dan Ekonomi Indonesia". www.kdei-taipei.org. Retrieved 2022-02-24.

- ^ Media Indonesia Online 2006-11-30

- ^ "ASIAN ALONE OR IN COMBINATION WITH ONE OR MORE OTHER RACES, AND WITH ONE OR MORE ASIAN CATEGORIES FOR SELECTED GROUPS". United States Census Bureau. United States Department of Commerce. 2022. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ "Race Reporting for the Asian Population by Selected Categories: 2010", 2010 Census Summary File 1, U.S. Census Bureau, archived from the original on 2016-10-12, retrieved 2012-02-21

- ^ Barnes, Jessica S.; Bennett, Claudette E. (February 2002), The Asian Population: 2000 (PDF), U.S. Census 2000, U.S. Department of Commerce, p. 9, retrieved 2009-09-30

- ^ 令和5年6月末現在における在留外国人数について

- ^ a b c d e "Data Agregat WNI yang Tercatat di Perwakilan RI" (PDF) (in Indonesian). General Elections Commission. 2019. Retrieved 2022-02-24.

- ^ "Department of Home Affairs, Country Profile - Indonesia". Retrieved 2022-09-11.

- ^ "People in Australia who were born in Indonesia". Retrieved 2023-03-06.

- ^ "Suriname". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 18 December 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- ^ "Profil Negara Suriname". Kementerian Luar Negeri Repulik Indonesia (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2022-02-27.

- ^ a b "Indonesian and Cambodia to Strengthen Cooperation in Combating Transnational Crimes and Protecting Indonesian Citizens". Kementerian Luar Negeri Repulik Indonesia. 2024-05-14. Retrieved 2024-07-25.

- ^ "Bertemu Sultan Brunei, Jokowi Akan Bahas Perlindungan WNI". kumparan (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2022-02-24.

- ^ a b Population by country of citizenship, sex, and urban/rural residence; each census, 1985–2004, United Nations Statistics Division, 2005, retrieved 2011-06-15

- ^ "Exploring Transnational Communities in the Philippines" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2008.

- ^ "42 Ribu Orang WNI di Korea Selatan | Databoks". databoks.katadata.co.id (in Indonesian). 2020-02-28. Retrieved 2022-02-24.

- ^ Habibah, Astrid Faidlatul (2020-02-03). Yuliastuti, Nusarina (ed.). "Menaker pastikan belum ada TKI di China terjangkit virus corona". Antara News (in Indonesian). Jakarta: antaranews.com. Retrieved 2022-02-26.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Immigrant and Emigrant Populations by Country of Origin and Destination". 10 February 2014.

- ^ "Uang Kuliah Gratis Ayo Kuliah Di Jerman Saja - | KEMENTERIAN LUAR NEGERI REPUBLIK INDONESIA". Kementerian Luar Negeri Repulik Indonesia (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2022-02-24.

- ^ "Ethnic origin population". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Statistics Canada. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ Immigrants in Brazil (2022)

- ^ "Relations between Turkey and Indonesia". Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- ^ "Jokowi Minta Menkumham Kaji Status Kewarganegaraan" (in Indonesian).

- ^ "Kemlu: 2,2 Juta WNI Tinggal di Luar Negeri" (in Indonesian).

- ^ "Bo Kaap: The History Behind the Cape Malays of Cape Town". pilotguides. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ "The Wanderers of Nusantara". roadsandkingdoms.com. 29 July 2015. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ 令和4年末現在における在留外国人数について

- ^ "Home | Student Helpr". studenthelpr.com. Retrieved 2024-03-10.

- ^ Snoj, Jure (18 December 2013). "Population of Qatar". Bqdoha.com. Archived from the original on 22 December 2013.

- ^ Ricklefs, M. C. (1994). A History of Modern Indonesia Since c. 1300. Stanford University Press.

- ^ Mohammed Saleh Benten, Menteri Arab Saudi Keturunan Banten. Ini Profilnya (Mohammed Saleh Benten, A Saudi Minister of Banten Descent. This is his Profile) (in Indonesian), Nusantarakini.com, March 2017, retrieved 23 September 2019

- ^ "English Not On Menu For Wednesday's Press Briefing". Malaysian National News Agency. 22 September 2005. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ "Meet Marvell" (PDF). Forbes Magazine. 14 August 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 October 2006.

- ^ Ember, Steve; Schonhardt, Sara (13 April 2011). "A Push to Get More Indonesians to Study in US". VoA. Retrieved 24 June 2016.