Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, chevalier de Lamarck (1 August 1744 – 18 December 1829), often known simply as Lamarck (/ləˈmɑːrk/;[1] French: [ʒɑ̃batist lamaʁk][2]), was a French naturalist, biologist, academic, and soldier. He was an early proponent of the idea that biological evolution occurred and proceeded in accordance with natural laws.[3]

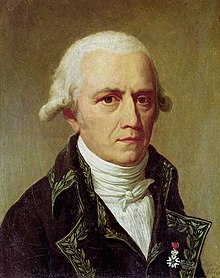

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck | |

|---|---|

Lamarck by Charles Thévenin, c. 1802 | |

| Born | 1 August 1744 |

| Died | 18 December 1829 (aged 85) |

| Known for | Evolution; inheritance of acquired characteristics; Philosophie zoologique |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

| Institutions | French Academy of Sciences; Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle; Jardin des Plantes |

| Author abbrev. (botany) | Lam. |

| Author abbrev. (zoology) | Lamarck |

Lamarck fought in the Seven Years' War against Prussia, and was awarded a commission for bravery on the battlefield.[4] Posted to Monaco, Lamarck became interested in natural history and resolved to study medicine.[5] He retired from the army after being injured in 1766, and returned to his medical studies.[5] Lamarck developed a particular interest in botany, and later, after he published the three-volume work Flore françoise (1778), he gained membership of the French Academy of Sciences in 1779. Lamarck became involved in the Jardin des Plantes and was appointed to the Chair of Botany in 1788. When the French National Assembly founded the Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle in 1793, Lamarck became a professor of zoology.

In 1801, he published Système des animaux sans vertèbres, a major work on the classification of invertebrates, a term which he coined.[6] In an 1802 publication, he became one of the first to use the term "biology" in its modern sense.[7][Note 1] Lamarck continued his work as a premier authority on invertebrate zoology. He is remembered, at least in malacology, as a taxonomist of considerable stature.

The modern era generally remembers Lamarck for a theory of inheritance of acquired characteristics, called Lamarckism (inaccurately named after him), soft inheritance, or use/disuse theory,[8] which he described in his 1809 Philosophie zoologique. However, the idea of soft inheritance long antedates him, formed only a small element of his theory of evolution, and was in his time accepted by many natural historians. Lamarck's contribution to evolutionary theory consisted of the first truly cohesive theory of biological evolution,[9] in which an alchemical complexifying force drove organisms up a ladder of complexity, and a second environmental force adapted them to local environments through use and disuse of characteristics, differentiating them from other organisms.[10] Scientists have debated whether advances in the field of transgenerational epigenetics mean that Lamarck was to an extent correct, or not.[11]

Biography

editJean-Baptiste Lamarck was born in Bazentin, Picardy, northern France,[5] as the 11th child in an impoverished aristocratic family.[Note 2] Male members of the Lamarck family had traditionally served in the French army. Lamarck's eldest brother was killed in combat at the Siege of Bergen op Zoom, and two other brothers were still in service when Lamarck was in his teenaged years. Yielding to the wishes of his father, Lamarck enrolled in a Jesuit college in Amiens in the late 1750s.[5]

After his father died in 1760, Lamarck bought himself a horse, and rode across the country to join the French army, which was in Germany at the time. Lamarck showed great physical courage on the battlefield in the Seven Years' War with Prussia, and he was even nominated for the lieutenancy.[5] Lamarck's company was left exposed to the direct artillery fire of their enemies, and was quickly reduced to just 14 men—with no officers. One of the men suggested that the puny, 17-year-old volunteer should assume command and order a withdrawal from the field; although Lamarck accepted command, he insisted they remain where they had been posted until relieved.

When their colonel reached the remains of their company, this display of courage and loyalty impressed him so much that Lamarck was promoted to officer on the spot. However, when one of his comrades playfully lifted him by the head, he sustained an inflammation in the lymphatic glands of the neck, and he was sent to Paris to receive treatment.[5] He was awarded a commission and settled at his post in Monaco. There, he encountered Traité des plantes usuelles, a botany book by James Francis Chomel.[5]

With a reduced pension of only 400 francs a year, Lamarck resolved to pursue a profession. He attempted to study medicine, and supported himself by working in a bank office.[5] Lamarck studied medicine for four years, but gave it up under his elder brother's persuasion. He was interested in botany, especially after his visits to the Jardin du Roi, and he became a student under Bernard de Jussieu, a notable French naturalist.[5] Under Jussieu, Lamarck spent 10 years studying French flora. In 1776, he wrote his first scientific essay—a chemical treatise.[12]

After his studies, in 1778, he published some of his observations and results in a three-volume work, entitled Flore française. Lamarck's work was respected by many scholars, and it launched him into prominence in French science. On 8 August 1778, Lamarck married Marie Anne Rosalie Delaporte.[13] Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, one of the top French scientists of the day, mentored Lamarck, and helped him gain membership to the French Academy of Sciences in 1779 and a commission as a royal botanist in 1781, in which he traveled to foreign botanical gardens and museums.[14] Lamarck's first son, André, was born on 22 April 1781, and he made his colleague André Thouin the child's godfather.

In his two years of travel, Lamarck collected rare plants that were not available in the Royal Garden, and also other objects of natural history, such as minerals and ores, that were not found in French museums. On 7 January 1786, his second son, Antoine, was born, and Lamarck chose Antoine Laurent de Jussieu, Bernard de Jussieu's nephew, as the boy's godfather.[15] On 21 April the following year, Charles René, Lamarck's third son, was born. René Louiche Desfontaines, a professor of botany at the Royal Garden, was the boy's godfather, and Lamarck's elder sister, Marie Charlotte Pelagie De Monet, was the godmother.[15] In 1788, Buffon's successor at the position of Intendant of the Royal Garden, Charles-Claude Flahaut de la Billaderie, comte d'Angiviller, created a position for Lamarck, with a yearly salary of 1,000 francs, as the keeper of the herbarium of the Royal Garden.[5]

In 1790, at the height of the French Revolution, Lamarck changed the name of the Royal Garden from Jardin du Roi to Jardin des Plantes, a name that did not imply such a close association with King Louis XVI.[16] Lamarck had worked as the keeper of the herbarium for five years before he was appointed curator and professor of invertebrate zoology at the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle in 1793.[5] During his time at the herbarium, Lamarck's wife gave birth to three more children before dying on 27 September 1792. With the official title of "Professeur d'Histoire naturelle des Insectes et des Vers", Lamarck received a salary of nearly 2,500 francs per year.[17] The following year, on 9 October, he married Charlotte Reverdy, who was 30 years his junior.[15] On 26 September 1794 Lamarck was appointed to serve as secretary of the assembly of professors for the museum for a period of one year. In 1797, Charlotte died, and he married Julie Mallet the following year; she died in 1819.[15]

In his first six years as professor, Lamarck published only one paper, in 1798, on the influence of the moon on the Earth's atmosphere.[5] Lamarck began as an essentialist who believed species were unchanging; however, after working on the molluscs of the Paris Basin, he grew convinced that transmutation or change in the nature of a species occurred over time.[5] He set out to develop an explanation, and on 11 May 1800 (the 21st day of Floreal, Year VIII, in the revolutionary timescale used in France at the time), he presented a lecture at the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle in which he first outlined his newly developing ideas about evolution.

In 1801, he published Système des Animaux sans Vertèbres, a major work on the classification of invertebrates. In the work, he introduced definitions of natural groups among invertebrates. He categorized echinoderms, arachnids, crustaceans, and annelids, which he separated from the old taxon for worms known as Vermes.[16] Lamarck was the first to separate arachnids from insects in classification, and he moved crustaceans into a separate class from insects.

In 1802, Lamarck published Hydrogéologie, and became one of the first to use the term biology in its modern sense.[7][18] In Hydrogéologie, Lamarck advocated a steady-state geology based on a strict uniformitarianism. He argued that global currents tended to flow from east to west, and continents eroded on their eastern borders, with the material carried across to be deposited on the western borders. Thus, the Earth's continents marched steadily westward around the globe.

That year, he also published Recherches sur l'Organisation des Corps Vivants, in which he drew out his theory on evolution. He believed that all life was organized in a vertical chain, with gradation between the lowest forms and the highest forms of life, thus demonstrating a path to progressive developments in nature.[19]

In his own work, Lamarck had favored the then-more traditional theory based on the classical four elements. During Lamarck's lifetime, he became controversial, attacking the more enlightened chemistry proposed by Lavoisier. He also came into conflict with the widely respected palaeontologist Georges Cuvier, who was not a supporter of evolution.[20] According to Peter J. Bowler, Cuvier "ridiculed Lamarck's theory of transformation and defended the fixity of species."[21] According to Martin J. S. Rudwick:

Cuvier was clearly hostile to the materialistic overtones of current transformist theorizing, but it does not necessarily follow that he regarded species origin as supernatural; certainly he was careful to use neutral language to refer to the causes of the origins of new forms of life, and even of man.[22]

Lamarck gradually turned blind; he died in Paris on 18 December 1829. When he died, his family was so poor, they had to apply to the Academie for financial assistance. Lamarck was buried in a common grave of the Montparnasse cemetery for just five years, according to the grant obtained from relatives. Later, the body was dug up along with other remains and was lost. Lamarck's books and the contents of his home were sold at auction, and his body was buried in a temporary lime pit.[23] After his death, Cuvier used the form of a eulogy to denigrate Lamarck:

[Cuvier's] éloge of Lamarck is one of the most deprecatory and chillingly partisan biographies I have ever read—though he was supposedly writing respectful comments in the old tradition of de mortuis nil nisi bonum.

— Gould, 1993[24]

Lamarckian evolution

editWhile he was working on Hydrogéologie (1802), Lamarck had the idea to apply the principle of erosion to biology. This led him to the basic principle of evolution, which saw the fluids in organs inheriting more complex forms and functions, thus passing on these traits to the organism's descendants.[12] This was a reversal from Lamarck's previous view, published in his Memoirs of Physics and Natural History (1797), in which he briefly refers to the immutability of species.[25]

Lamarck stressed two main themes in his biological work (neither of them to do with soft inheritance). The first was that the environment gives rise to changes in animals. He cited examples of blindness in moles, the presence of teeth in mammals and the absence of teeth in birds as evidence of this principle. The second principle was that life was structured in an orderly manner and that many different parts of all bodies make possible the organic movements of animals.[19]

Although he was not the first thinker to advocate organic evolution, he was the first to develop a truly coherent evolutionary theory.[10] He outlined his theories regarding evolution first in his Floreal lecture of 1800, and then in three later published works:

- Recherches sur l'organisation des corps vivants, 1802.

- Philosophie zoologique, 1809.

- Histoire naturelle des animaux sans vertèbres, (in seven volumes, 1815–22).

Lamarck employed several mechanisms as drivers of evolution, drawn from the common knowledge of his day and from his own belief in the chemistry before Lavoisier. He used these mechanisms to explain the two forces he saw as constituting evolution: force driving animals from simple to complex forms and a force adapting animals to their local environments and differentiating them from each other. He believed that these forces must be explained as a necessary consequence of basic physical principles, favoring a materialistic attitude toward biology.

Le pouvoir de la vie: The complexifying force

editLamarck referred to a tendency for organisms to become more complex, moving "up" a ladder of progress. He referred to this phenomenon as Le pouvoir de la vie or la force qui tend sans cesse à composer l'organisation (The force that perpetually tends to make order). Lamarck believed in the ongoing spontaneous generation of simple living organisms through action on physical matter by a material life force.[27][26]

Lamarck ran against the modern chemistry promoted by Lavoisier (whose ideas he regarded with disdain), preferring to embrace a more traditional alchemical view of the elements as influenced primarily by earth, air, fire, and water. He asserted that once living organisms form, the movements of fluids in living organisms naturally drove them to evolve toward ever greater levels of complexity:[27]

The rapid motion of fluids will etch canals between delicate tissues. Soon their flow will begin to vary, leading to the emergence of distinct organs. The fluids themselves, now more elaborate, will become more complex, engendering a greater variety of secretions and substances composing the organs.

— Histoire naturelle des animaux sans vertebres, 1815

He argued that organisms thus moved from simple to complex in a steady, predictable way based on the fundamental physical principles of alchemy. In this view, simple organisms never disappeared because they were constantly being created by spontaneous generation in what has been described as a "steady-state biology". Lamarck saw spontaneous generation as being ongoing, with the simple organisms thus created being transmuted over time becoming more complex. He is sometimes regarded as believing in a teleological (goal-oriented) process where organisms became more perfect as they evolved, though as a materialist, he emphasized that these forces must originate necessarily from underlying physical principles. According to the paleontologist Henry Fairfield Osborn, "Lamarck denied, absolutely, the existence of any 'perfecting tendency' in nature, and regarded evolution as the final necessary effect of surrounding conditions on life."[28] Charles Coulston Gillispie, a historian of science, has written "life is a purely physical phenomenon in Lamarck", and argued that Lamarck's views should not be confused with the vitalist school of thought.[29]

L'influence des circonstances: The Adaptive Force

editThe second component of Lamarck's theory of evolution was the adaptation of organisms to their environment. This could move organisms upward from the ladder of progress into new and distinct forms with local adaptations. It could also drive organisms into evolutionary blind alleys, where the organism became so finely adapted that no further change could occur. Lamarck argued that this adaptive force was powered by the interaction of organisms with their environment, by the use and disuse of certain characteristics.

First law: use and disuse

edit- First Law: In every animal which has not passed the limit of its development, a more frequent and continuous use of any organ gradually strengthens, develops and enlarges that organ, and gives it a power proportional to the length of time it has been so used; while the permanent disuse of any organ imperceptibly becomes weak and deteriorates it, and progressively diminishes its functional capacity or ability to function as expected, until it finally disappears.[30]

Second law: inheritance of acquired characteristics

edit- Second Law: All the acquisitions or losses wrought by nature on individuals, through the influence of the environment in which their race has long been placed, and hence through the influence of the predominant use or permanent disuse of any organ; all these are preserved by reproduction to the new individuals which arise, provided that the acquired modifications are common to both sexes, or at least to the individuals which produce the young.[30]

The last clause of this law introduces what is now called soft inheritance, the inheritance of acquired characteristics, or simply "Lamarckism", though it forms only a part of Lamarck's thinking.[31] However, in the field of epigenetics, evidence is growing that soft inheritance plays a part in the changing of some organisms' phenotypes; it leaves the genetic material (DNA) unaltered (thus not violating the central dogma of biology) but prevents the expression of genes,[32] such as by methylation to modify DNA transcription; this can be produced by changes in behaviour and environment. Many epigenetic changes are heritable to a degree. Thus, while DNA itself is not directly altered by the environment and behavior except through selection, the relationship of the genotype to the phenotype can be altered, even across generations, by experience within the lifetime of an individual. This has led to calls for biology to reconsider Lamarckian processes in evolution in light of modern advances in molecular biology.[33]

Religious views

editIn his book Philosophie zoologique, Lamarck referred to God as the "sublime author of nature". Lamarck's religious views are examined in the book Lamarck, the Founder of Evolution (1901) by Alpheus Packard. According to Packard from Lamarck's writings, he may be regarded as a deist.[34]

The philosopher of biology Michael Ruse described Lamarck, "as believing in God as an unmoved mover, creator of the world and its laws, who refuses to intervene miraculously in his creation."[35] Biographer James Moore described Lamarck as a "thoroughgoing deist".[36]

The historian Jacques Roger has written, "Lamarck was a materialist to the extent that he did not consider it necessary to have recourse to any spiritual principle... his deism remained vague, and his idea of creation did not prevent him from believing everything in nature, including the highest forms of life, was but the result of natural processes."[37]

Legacy

editLamarck is known largely for his views on evolution, which have been dismissed in favour of developments in Darwinism. His theory of evolution only achieved fame after the publication of Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species (1859), which spurred critics of Darwin's new theory to fall back on Lamarckian evolution as a more well-established alternative.[38]

Lamarck is usually remembered for his belief in the then commonly held theory of inheritance of acquired characteristics, and the use and disuse model by which organisms developed their characteristics. Lamarck incorporated this belief into his theory of evolution, along with other common beliefs of the time, such as spontaneous generation.[26] The inheritance of acquired characteristics (also called the theory of adaptation or soft inheritance) was rejected by August Weismann in the 1880s[Note 3] when he developed a theory of inheritance in which germ plasm (the sex cells, later redefined as DNA), remained separate and distinct from the soma (the rest of the body); thus, nothing which happens to the soma may be passed on with the germ plasm. This model allegedly underlies the modern understanding of inheritance.

Lamarck constructed one of the first theoretical frameworks of organic evolution. While this theory was generally rejected during his lifetime,[39] Stephen Jay Gould argues that Lamarck was the "primary evolutionary theorist", in that his ideas, and the way in which he structured his theory, set the tone for much of the subsequent thinking in evolutionary biology, through to the present day.[40] Developments in epigenetics, the study of cellular and physiological traits that are heritable by daughter cells and not caused by changes in the DNA sequence, have caused debate about whether a "neolamarckist" view of inheritance could be correct: Lamarck was not in a position to give a molecular explanation for his theory. Eva Jablonka and Marion Lamb, for example, call themselves neolamarckists.[11][33] Reviewing the evidence, David Haig argued that any such mechanisms must themselves have evolved through natural selection.[11]

Darwin allowed a role for use and disuse as an evolutionary mechanism subsidiary to natural selection, most often in respect of disuse.[Note 4] He praised Lamarck for "the eminent service of arousing attention to the probability of all change in the organic... world, being the result of law, not miraculous interposition".[42] Lamarckism is also occasionally used to describe quasi-evolutionary concepts in societal contexts, though not by Lamarck himself. For example, the memetic theory of cultural evolution is sometimes described as a form of Lamarckian inheritance of nongenetic traits.

Species and other taxa named by Lamarck

editDuring his lifetime, Lamarck named a large number of species, many of which have become synonyms. The World Register of Marine Species gives no fewer than 1,634 records.[43] The Indo-Pacific Molluscan Database gives 1,781 records.[44] Among these are some well-known families such as the ark clams (Arcidae), the sea hares (Aplysiidae), and the cockles (Cardiidae). The International Plant Names Index gives 58 records, including a number of well-known genera such as the mosquito fern (Azolla).[citation needed]

Species named in his honour

editThe honeybee subspecies Apis mellifera lamarckii is named after Lamarck, as well as the bluefire jellyfish (Cyaneia lamarckii). A number of plants have also been named after him, including Amelanchier lamarckii (juneberry), Digitalis lamarckii, and Aconitum lamarckii, as well as the grass genus Lamarckia.

The International Plant Names Index gives 116 records of plant species named after Lamarck.[45]

Among the marine species, no fewer than 103 species or genera carry the epithet "lamarcki", "lamarckii" or "lamarckiana", but many have since become synonyms. Marine species with valid names include:[43]

- Acropora lamarcki Veron, 2002

- Agaricia lamarcki Milne Edwards & Haime, 1851

- Ascaltis lamarcki (Haeckel, 1870)

- Bursa lamarckii (Deshayes, 1853), a frog snail

- Carinaria lamarckii Blainville, 1817, a small planktonic sea snail

- Caligodes lamarcki Quidor, 1913

- Cyanea lamarckii Péron & Lesueur 1810

- Cyllene desnoyersi lamarcki Cernohorsky, 1975

- Erosaria lamarckii (J. E. Gray, 1825), a cowrie

- Genicanthus lamarck (Lacepède, 1802), a Saltwater Angelfish.

- Gorgonocephalus lamarckii (Müller & Troschel, 1842)

- Gyroidinoides lamarckiana (d´Orbigny, 1839)

- Lamarckdromia Guinot & Tavares, 2003

- Lamarckina Berthelin, 1881

- Lobophytum lamarcki Tixier-Durivault, 1956

- Marginella lamarcki Boyer, 2004, a small sea snail

- Megerlina lamarckiana (Davidson, 1852)

- Meretrix lamarckii Deshayes, 1853

- Morum lamarckii (Deshayes, 1844), a small sea snail

- Mycetophyllia lamarckiana Milne Edwards & Haime, 1848,

- Neotrigonia lamarckii (Gray, 1838)

- Olencira lamarckii Leach, 1818

- Oenothera lamarckiana

- Petrolisthes lamarckii (Leach, 1820)

- Pomatoceros lamarckii (Quatrefages, 1866)

- Quinqueloculina lamarckiana d´Orbigny, 1839

- Raninoides lamarcki A. Milne-Edwards & Bouvier, 1923

- Rhizophora x lamarckii Montr.

- Siphonina lamarckana Cushman, 1927

- Solen lamarckii Chenu, 1843

- Spondylus lamarckii Chenu, 1845, a thorny oyster

- Xanthias lamarckii (H. Milne Edwards, 1834)

Major works

edit- 1778 Flore françoise, ou, Description succincte de toutes les plantes qui croissent naturellement en France 1st ed.

- 2nd ed. 1795, 3rd 1805 (de Candolle ed.)

- 1795 Recherches sur les causes des principaux faits physiques (in French). Vol. 1. Milano: Luigi Veladini. 1795.

- 1809. Philosophie zoologique, ou Exposition des considérations relatives à l'histoire naturelle des animaux..., Paris. Translated with introduction and commentary in 1914 by Hugh S. R. Elliot as Zoological Philosophy. Arguably the most comprehensive discussion of the topic of Lamarckism and more of Lamarck's views.

- Lamarck, Jean-Baptiste (1783–1808). Encyclopédie méthodique. Botanique. Paris: Panckoucke. (see Encyclopédie méthodique)

- Supplement 1810–1817

- L'Illustration des genres, vol. I: 1791, vol. II: 1793, vol. III: 1800, Supplement by Poiret 1823

On invertebrate classification:

- 1801. Système des animaux sans vertèbres, ou tableau général des classes, des ordres et des genres de ces animaux; présentant leurs caractères essentiels et leur distribution, d'après la considération de leurs..., Paris, Detreville, VIII: 1–432.

- 1815–22. Histoire naturelle des animaux sans vertèbres, présentant les caractères généraux et particuliers de ces animaux..., Tome 1 (1815): 1–462; Tome 2 (1816): 1–568; Tome 3 (1816): 1–586; Tome 4 (1817): 1–603; Tome 5 (1818): 1–612; Tome 6, Pt.1 (1819): 1–343; Tome 6, Pt.2 (1822): 1–252; Tome 7 (1822): 1–711.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ The term "biology" was also introduced independently by Thomas Beddoes (in 1799), by Karl Friedrich Burdach (in 1800) and by Gottfried Reinhold Treviranus (Biologie oder Philosophie der lebenden Natur, 1802).

- ^ His noble title was chevalier, which is French for knight.

- ^ It was rejected during Lamarck's lifetime by William Lawrence, whose anticipation of hard inheritance has often gone unnoticed.[citation needed]

- ^ Ernst Mayr commented: "Curiously few evolutionists have noted that, in addition to natural selection, Darwin admits use and disuse as an important evolutionary mechanism. In this he is perfectly clear. For instance,…on page 137 he says that the reduced size of the eyes in moles and other burrowing mammals is 'probably due to gradual reduction from disuse, but aided perhaps by natural selection'. In the case of cave animals, when speaking of the loss of eyes, he says, 'I attribute their loss wholly to disuse' (p137) On page 455 he begins unequivocally, 'At whatever period of life disuse or selection reduces an organ…' The importance he gives to use or disuse is indicated by the frequency with which he invokes this agent of evolution in the Origin. I find references on pages 11, 43, 134, 135, 136, 137, 447, 454, 455, 472, 479, and 480."[41]

References

edit- ^ "Lamarck". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ Dudenredaktion, Kleiner & Knöbl (2015), pp. 484, 541.

- ^ "Jean-Baptiste Lamarck | Biography, Theory of Evolution & Facts". Encyclopaedia Britannica. 20 July 1998. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ Damkaer (2002), p. 117.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Packard (1901), p. 15.

- ^ "Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744-1829)". ucmp.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- ^ a b Coleman (1977), pp. 1–2.

- ^ Jurmain et al. (2011), pp. 27–39.

- ^ Darwin (2001), p. 44.

- ^ a b Gould (2002), p. 187.

- ^ a b c Haig (2007), pp. 415–428.

- ^ a b Gillispie (1960), p. 275.

- ^ Mantoy (1968), p. 19.

- ^ Packard (1901), pp. 20–21.

- ^ a b c d Bange & Corsi (n.d.).

- ^ a b Damkaer (2002), p. 118.

- ^ Szyfman (1982), p. 13.

- ^ Osborn (1905), p. 159.

- ^ a b Osborn (1905), p. 160.

- ^ Curtis, Millar & Lambert (2018).

- ^ Bowler (2003), p. 110.

- ^ Rudwick (1998), p. 83.

- ^ Waggoner & Speer (1998).

- ^ Gould (1993) Foreword

- ^ Gillispie (1960), p. 273.

- ^ a b c Gould (2001), pp. 119–121.

- ^ a b Larson (2004), pp. 38–41.

- ^ Osborn (1894), p. 163.

- ^ Gillispie (1960), p. 272.

- ^ a b Weber (2000), p. 55.

- ^ Bowler (1989), p. 86.

- ^ Fitzpatrick (2006).

- ^ a b Jablonka, Lamb & Avital (1998), pp. 206–210.

- ^ Packard (2008), pp. 217–22.

- ^ Ruse (1999), p. 11.

- ^ Moore (1981), p. 344.

- ^ Roger (1986), p. 291.

- ^ Gillispie (1960), p. 269.

- ^ Mitchell (1911), p. 22.

- ^ Gould (2002) pp. 170–197.

- ^ Mayr (1964), pp. xxv–xxvi.

- ^ Darwin (1861–82), 3rd edition, "Historical sketch", page xiii

- ^ a b "WoRMS: species named by Lamarck". Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- ^ "Indo-Pacific Molluscan Species Database". The Academy of Natural Sciences. 17 May 2006. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ^ "International Plant Names Index". ipni.org. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ^ International Plant Names Index. Lam.

Bibliography

edit- Bange, Raphaël; Corsi, Pietro (n.d.). "Chronologie de la vie de Jean-Baptiste Lamarck" (in French). Centre national de la recherche scientifique. Archived from the original on 12 April 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- Bowler, Peter (1989). Evolution : the history of an idea (Revised ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06386-0. OCLC 17841313.

- Bowler, Peter J. (2003). Evolution: the History of an Idea (3rd ed.). California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23693-6.

- Burkhardt, Richard W. Jr. (1970). "Lamarck, evolution, and the politics of science". Journal of the History of Biology. 3 (2): 275–298. doi:10.1007/bf00137355. JSTOR 4330543. PMID 11609655. S2CID 33402055.

- Coleman, William L. (1977). Biology in the Nineteenth Century: problems of form, function, and transformation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29293-1.

- Curtis, Caitlin; Millar, Craig; Lambert, David (September 2018). "The Sacred Ibis debate: The first test of evolution". PLOS Biology. 16 (9): e2005558. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.2005558. PMC 6159855. PMID 30260949.

- Cuvier, Georges (January 1836). "Elegy of Lamarck". Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal. 20: 1–22.

- Damkaer, David M. (2002). The Copepodologist's Cabinet: a Biographical and Bibliographical History. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. ISBN 978-0-87169-240-5.

- Darwin, Charles (1861–1882). "Historical sketch". On the Origin of Species (3rd–6th ed.). London: John Murray.

- Darwin, Charles (2001). Appleman, Philip (ed.). Darwin: Texts, Commentary. Norton critical editions in the history of ideas (3rd ed.). Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-95849-2.

- Delange, Yves (1984). Lamarck, sa vie, son œuvre. Arles: Actes Sud. ISBN 978-2-903098-97-1.

- Dudenredaktion; Kleiner, Stefan; Knöbl, Ralf (2015) [First published 1962]. Das Aussprachewörterbuch [The Pronunciation Dictionary] (in German) (7th ed.). Berlin: Dudenverlag. ISBN 978-3-411-04067-4.

- Fitzpatrick, Tony (2006). "Researcher gives hard thoughts on soft inheritance: above and beyond the gene". Washington University in St. Louis. Archived from the original on 8 January 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- Gillispie, Charles Coulston (1960). The Edge of Objectivity: An Essay in the History of Scientific Ideas. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02350-6.

- Gould, Stephen Jay (1993). "Foreword". In Jean Chandler Smith (ed.). Georges Cuvier: an annotated bibliography of his published works. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 978-1-56098-199-2.

- ——— (2001). The lying stones of Marrakech : penultimate reflections in natural history. Vintage. ISBN 978-0-09-928583-0.

- ——— (2002). The Structure of Evolutionary Theory. Harvard: Belknap Harvard. ISBN 978-0-674-00613-3.

- Haig, David (2007). "Weismann Rules! OK? Epigenetics and the Lamarckian temptation". Biology and Philosophy. 22 (3): 415–428. doi:10.1007/s10539-006-9033-y. S2CID 16322990.

- Jablonka, Eva; Lamb, Marion J.; Avital, Eytan (1998). "'Lamarckian' mechanisms in darwinian evolution". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 13 (5): 206–210. doi:10.1016/s0169-5347(98)01344-5. PMID 21238269.

- Jablonka, Eva (2006). Evolution in Four Dimensions: Genetic, Epigenetic, Behavioral, and Symbolic Variation in the History of Life. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-60069-9.

- Jordanova, Ludmilla (1984). Lamarck, past master. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-287587-7.

- Jurmain, Robert; Lynn Kilgore; Wenda Trevathan; Russell L. Ciochon (2011). Introduction to Physical Anthropology (13th ed.). Wadsworth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-111-29793-0.

- Lamarck, J. B. (1914). Zoological Philosophy. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Larson, Edward J (May 2004). ""A Growing sense of progress". Evolution: The remarkable history of a Scientific Theory. New York: Modern Library. ISBN 9780679642886.

- Mantoy, Bernard (1968). Lamarck. Savants du monde entier. Vol. 36. Paris: Seghers.

- Mayr, Ernst (1964) [1859]. "Introduction". In Charles Darwin (ed.). On the Origin of Species: a Facsimile of the First Edition. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-63752-8.

- Mitchell, Peter Chalmers (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Moore, James R. (1981). The Post-Darwinian Controversies: A Study of the Protestant Struggle to Come to Terms with Darwin in Great Britain and America 1870–1900. Cambridge University Press.

- Osborn, Henry Fairfield (1894). From the Greeks to Darwin. Macmillan and Company.

- Osborn, Henry Fairfield (1905). From the Greeks to Darwin: an outline of the development of the evolution idea (2nd ed.). New York: Macmillan.

- Packard, Alpheus Spring (1901). Lamarck, the founder of Evolution: his life and work with translations of his writing on organic evolution. New York: Longmans, Green.

- Packard, Alpheus Spring (2008) [1901]. Lamarck, The Founder of Evolution. Wildhern Press.

- Roger, Jacques (1986). "The Mechanist Conception of Life". In Lindberg, David C.; Numbers, Ronald L. (eds.). God and Nature: Historical Essays on the Encounter Between Christianity and Science. University of California Press.

- Rudwick, Martin J. S. (1998). Georges Cuvier, Fossil Bones, and Geological Catastrophes: New Translations and Interpretations of the Primary Texts. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-73107-0.

- Ruse, Michael (1999). The Darwinian Revolution: Science Red in Tooth and Claw. University of Chicago Press.

- Szyfman, Léon (1982). Jean-Baptiste Lamarck et son époque. Paris: Masson. ISBN 978-2-225-76087-7.

- Junko A. Arai; Shaomin Li; Dean M. Hartley; Larry A. Feig (2009). "Transgenerational rescue of a genetic defect in long-term potentiation and memory formation by juvenile enrichment". The Journal of Neuroscience. 29 (5): 1496–1502. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5057-08.2009. PMC 3408235. PMID 19193896.

- Ross Honeywill (2008). Lamarck's Evolution: Two Centuries of Genius and Jealousy. Pier 9. ISBN 978-1-921208-60-7.

- Waggoner, Ben; Speer, B. R. (2 September 1998). "Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744-1829)". UCMP Berkeley. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- Weber, A. S. (2000). Nineteenth-Century Science: An Anthology. Broadview Press. ISBN 978-1-55111-165-0.

External links

edit- The Imaginary Lamarck: A Look at Bogus "History" in Schoolbooks by Michael Ghiselin

- Works by Jean-Baptiste Lamarck at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Jean-Baptiste Lamarck at the Internet Archive

- Epigenetics: Genome, Meet Your Environment

- Science Revolution Followers of Lamarck

- Encyclopédie Méthodique: Botanique At: Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Jean-Baptiste Lamarck: works and heritage, online materials about Lamarck (23,000 files of Lamarck's herbarium, 11,000 manuscripts, books, etc.) edited online by Pietro Corsi (Oxford University) and realised by CRHST-CNRS in France.

- Biography of Lamarck at University of California Museum of Paleontology

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 101–102.

- Memoir of Lamarck by James Duncan

- Lamarck's writings are available in facsimile (PDF) and in Word format (in French) at www.lamarck.cnrs.fr. The search engine allows full text search.

- Recherches sur l'organisation des corps vivans (1801) – fully digitized facsimile from Linda Hall Library.

- Hydrogéologie (1802) – digitized facsimile from Linda Hall Library

- Lamarck and Natural Selection, BBC Radio 4 discussion with Sandy Knapp, Steve Jones and Simon Conway Morris (In Our Time, 26 December 2003)