The June Rebellion, or the Paris Uprising of 1832 (French: Insurrection républicaine à Paris en juin 1832), was an anti-monarchist insurrection of Parisian republicans on 5 and 6 June 1832.

| June Rebellion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of July Revolution | |||||||

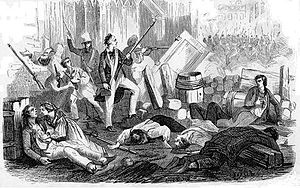

An 1870 illustration depicting the rebellion | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 30,000 | 3,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 73 killed, 344 wounded[1] | 93 killed, 291 wounded[1] | ||||||

The rebellion originated in an attempt by republicans to reverse the establishment in 1830 of the July Monarchy of Louis Philippe, shortly after the death of the King's powerful supporter and President of the Council, Casimir Pierre Périer, on 16 May 1832. On 1 June 1832, Jean Maximilien Lamarque, a popular former Army commander who became a member of the French parliament and was critical of the monarchy, died of cholera. The riots that followed his funeral sparked the rebellion. This was the last outbreak of violence linked with the July Revolution of 1830.

The French author Victor Hugo memorialized the rebellion in his 1862 novel Les Misérables, and it figures prominently in the stage musical and films that are based on the book.

Background

editIn the 1830 July Revolution, the elected Chamber of Deputies had established a constitutional monarchy and replaced Charles X of the House of Bourbon with his more liberal cousin Louis-Philippe. This angered republicans who saw one king replaced by another, and by 1832 there was a sentiment that their revolution, for which many had died, had been stolen.[2] However, over and above the easily provoked 'fury' or 'rage' of the Parisian population (at the differences between their poverty and the differences in income and opportunities of the bourgeoisie and the aristocracy), Bonapartists for their part lamented the loss of Napoleon's empire, and the Legitimists supported the deposed Bourbon dynasty, seeking to empower the man they regarded as the true king: Charles's grandson and designated successor Henri, Count of Chambord.[citation needed]

Causes and catalysts

editLeading up to the rebellion, there were significant economic problems, particularly acute in the period from 1827 to 1832. Harvest failures, food shortages, and increases in the cost of living created discontent throughout the classes. In the spring of 1832, Paris suffered a widespread outbreak of cholera, which ended with a death toll of 18,402 in the city and 100,000 across France. The poor neighbourhoods of Paris were devastated by the disease, arousing suspicion that the government had poisoned wells.[3]: 57–58

The epidemic soon claimed two well-known victims. Prime Minister Casimir Perier fell sick and died on 16 May, and the hero of the Napoleonic wars and reformer Jean Maximilien Lamarque died on 1 June. The conservative Perier was given a grand state funeral. The funeral of the popular Lamarque—described by Hugo as "loved by the people because he accepted the chances the future offered, loved by the mob because he served the emperor well"—was an opportunity to demonstrate the strength of the opposition.[3]: 58

The monarchy of Louis Philippe, which had become the government of the middle class, was now attacked from two opposite sides at once.[4]

Before these two deaths, there had been two significant rebellions. In France's second city, Lyon, a workers' uprising known as the Canut revolt had occurred in December 1831, caused by economic hardship. Troops were sent in after members of the local National Guard defected to the rebels.[5] In February 1832 in Paris supporters of the Bourbons—the Legitimists, or Carlists as they were called by their adversaries—made an attempt to carry off the royal family in what would become known as the "conspiracy of rue des Prouvaires".[4]

This was followed by an insurrection in the Bourbon heartland of the Vendée led by Caroline, Duchess of Berry, mother of Henri, Count of Chambord, the Legitimist claimant to the throne as 'Henri V'. The duchess was captured in late 1832 and imprisoned until 1833. After this, the Legitimists renounced war and fell back on the press as a weapon.[4]

Insurrections

editThe republicans were led by secret societies, formed of the most determined and ferocious members of their movement. These groups planned to provoke riots similar to those that had led to the 1830 July Revolution against the ministers of Charles X. The "Society of the Rights of Man" was one of the most instrumental. It was organized like an army, divided into sections of twenty members each (to evade the law that forbade the association of more than twenty persons), with a president and vice president for each section.[4]

The republican conspirators made their move at the public funeral of General Lamarque on 5 June. Groups of demonstrators took charge of the cortege and redirected it to the Place de la Bastille, where the Revolution had begun in 1789.[2]

Parisian workers and local youth were reinforced by Polish, Italian and German refugees, who had fled to Paris in the aftermath of crackdowns on republican and nationalist activities in their various homelands. They gathered around the catafalque on which the body rested. Speeches were made about Lamarque's support for Polish and Italian liberty, of which he had been a strong advocate in the months before his death. When a red flag bearing the words La Liberté ou la Mort ("Liberty or Death") was raised, the crowd broke into disorder and shots were exchanged with government troops.[2] The Marquis de Lafayette, who had given a speech in praise of Lamarque, called for calm, but the outbreak spread.[6]

The subsequent uprising put the roughly 3,000 insurgents in control of much of the eastern and central districts of Paris, between Chatelet, the Arsenal and the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, for one night. Cries were heard that the rioters would sup at the Tuileries Palace that evening. However, the rebellion failed to spread further.[7]

During the night of 5–6 June the 20,000 part-time militiamen of the Paris National Guard were reinforced by about 40,000 regular army troops under the command of the Comte de Lobau. This force occupied the peripheral districts of the capital.[7]

The insurgents made their stronghold in the Faubourg Saint-Martin, in the historic city center. They built barricades in the narrow streets around rue Saint-Martin and rue Saint-Denis.[2]

On the morning of 6 June the last rebels were surrounded at the intersection of rues Saint-Martin and Saint-Merry. At this point Louis-Philippe decided to show himself in the streets to confirm that he was still in control of the capital.[3]: 60 Returning to Paris from Saint-Cloud, he met his ministers and generals at the Tuileries and declared a state of siege, then rode through the area of the rising, to the applause of the troops.

The final struggle came at the Cloître Saint-Merry,[4] where fighting continued until the early evening of 6 June. Total casualties in the rising were about 800. The army and national guard lost 73 killed and 344 wounded; on the insurgent side there were 93 killed and 291 wounded.[1] The forces of the insurrection were spent.

Aftermath

editThe government portrayed the rebels as an extremist minority. Louis-Philippe had shown more energy and personal courage than his Bourbon predecessor Charles X had during the July Revolution two years before.[7] When the king appeared in public, his supporters greeted him with cheers. General Sébastini, the Foreign Minister, who directed government forces, stated that local citizens caught up in events congratulated him: "They accepted us with cries of Vive le Roi [Long live the King] and Vive la liberté [Long live Liberty], showing their joy at the success we had just obtained". Subsequent identification of rebels revealed that most (66%) were working-class, a high proportion being construction workers. Most others (34%) were shopkeepers or clerks.[3]: 60

A large number of weapons were confiscated in raids, and there were fears that martial law would be imposed. The government, which had come to power in a revolution, distanced itself from its own revolutionary past, famously removing from view Delacroix's painting Liberty Leading the People, which had been commissioned to commemorate the events of 1830. According to Albert Boime, "After the uprising at the funeral of Lamarque in June 1832, it was never again openly displayed for fear of setting a bad example".[8]

A young painter, Michel Geoffroy, was charged with starting the rebellion by waving the red flag. He was sentenced to death, but a series of legal appeals led to a prison sentence. The real flag-bearer was found a month later, and imprisoned for just a month due to his obvious mental instability. Seven of the 82 trials led to other death sentences, all commuted to terms of imprisonment.[3]: 61

Republicans used the trials to build support for their cause. Several rebels delivered republican speeches at their trial, including Charles Jeanne, one of the working-class leaders, who proudly defended his actions. He was convicted and imprisoned, and became a republican martyr.[3]: 62 A pamphlet published in 1836 compared the last stand of the republicans to the heroic resistance of the 300 Spartans at the Battle of Thermopylae:[3]: 14

A republican is virtue, perseverance; is devotion personified...[he] is Leonidas dying at Thermopylae, at the head of his 300 Spartans; he is also the 72 heroes who defended during 48 hours the approaches of the Cloître Saint-Merry from 60,000 men and who… threw themselves onto bayonets to obtain a glorious death.

Louis-Philippe's regime was finally overthrown in the French Revolution of 1848, though the subsequent French Second Republic was short-lived. In the 1848 Revolution, Friedrich Engels published a retrospective in which he analyzed the tactical errors which led to the failure of the 1832 uprising, and drew lessons for the 1848 revolt. The main strategic deficit, he argued, was the failure to march immediately on the centre of power, the Hôtel de Ville.[9]

Victor Hugo and Les Misérables

editOn 5 June 1832, young Victor Hugo was writing a play in the Tuileries Gardens when he heard the sound of gunfire from the direction of Les Halles. The park-keeper had to unlock the gate of the deserted gardens to let Hugo out. Instead of hurrying home, he followed the sounds through the empty streets, unaware that half of Paris had already fallen to the revolutionaries. All about Les Halles were barricades. Hugo headed north up rue Montmartre, then turned right onto Passage du Saumon (currently called rue Bachaumont), the last turning before rue du Cadran (currently called rue Léopold-Bellan), which prior to 1807 had been called rue du Bout du Monde. When he was halfway down the alley, the grilles at either end were slammed shut. Hugo was surrounded by barricades and found shelter between some columns in the street, where all the shops were shuttered. For a quarter of an hour, bullets flew both ways.[10]

In his novel Les Misérables, published thirty years later in 1862, Hugo depicts the period leading up to this rebellion and follows the lives and interactions of several characters over a twenty-year period. The novel begins in 1815, the year of Napoleon's final defeat and climaxes with the battles of the 1832 June Rebellion. An outspoken republican activist, Hugo unquestionably favored the revolutionaries, although in Les Miserables he wrote about Louis-Philippe in sympathetic terms, as well as criticising him.[11]

Les Misérables gave the relatively little-known 1832 rebellion widespread renown. The novel is one of the few works of literature that discuss this June Rebellion and the events leading up to it, though many who have not read the book often wrongly assume that it takes place either during the more widely known French Revolution of 1789–1799 or the French Revolution of 1848.[12]

References

edit- ^ a b c Duckett, William (ed.). Dictionnaire de la conversation et de la lecture (in French). Vol. 11. p. 702.

- ^ a b c d Traugott, Mark (2010). The Insurgent Barricade. University of California Press. pp. 4–8. ISBN 978-0-520-94773-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g Harsin, Jill (2002). Barricades: The War of the Streets in Revolutionary Paris, 1830–1848. New York: Palgrave. ISBN 978-0-312-29479-3.

- ^ a b c d e Seignobos, Charles (1900). A Political History of Europe, Since 1814. Translated by Macvane, Silas Marcus. New York: Henry Holt and Company. pp. 136–138.

- ^ Antonetti, Guy (2002). Louis-Philippe (in French). Fayard. p. 673. ISBN 978-2-7028-7276-5.

- ^ Sarrans, Bernard (1832). Memoirs of General Lafayette and of the French Revolution of 1830. Vol. 2. London: R. Bentley. p. 393.

- ^ a b c Mansel, Philip (2003). Paris Between Empires: Monarchy and Revolution, 1814–1852. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 285. ISBN 978-0-312-30857-5.

- ^ Boime, Albert (15 September 2008). Art in an Age of Civil Struggle, 1848–1871. University of Chicago Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-226-06342-3.

- ^ Engels, Frederick (1 July 1848). "The June Revolution: The Course of the Paris Uprising". Neue Rheinische Zeitung. Translated by the Marx-Engels Institute.

- ^ Graham, Robb (1998). Victor Hugo: A Biography. W.W. Norton and Company.

- ^ Tombs, Robert (2013). Introduction. Les Misérables. By Hugo, Victor. Penguin UK. p. 14.

- ^ Haven, Cynthia (December 2012). "Enjoy Les Misérables. But please, get the history straight". The Book Haven. Stanford University. Retrieved 5 June 2019.