The integumentary system is the set of organs forming the outermost layer of an animal's body. It comprises the skin and its appendages, which act as a physical barrier between the external environment and the internal environment that it serves to protect and maintain the body of the animal. Mainly it is the body's outer skin.

| Integumentary system | |

|---|---|

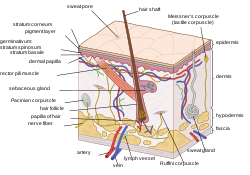

Cross-section of all skin layers | |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D034582 |

| TA98 | A16.0.00.001 |

| TA2 | 7040 |

| TH | H3.12.00.0.00001 |

| FMA | 72979 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The integumentary system includes skin, hair, scales, feathers, hooves, claws, and nails. It has a variety of additional functions: it may serve to maintain water balance, protect the deeper tissues, excrete wastes, and regulate body temperature, and is the attachment site for sensory receptors which detect pain, sensation, pressure, and temperature.

Structure

editSkin

editThe skin is one of the largest organs of the body. In humans, it accounts for about 12 to 15 percent of total body weight and covers 1.5 to 2 m2 of surface area.[1]

The skin (integument) is a composite organ, made up of at least two major layers of tissue: the epidermis and the dermis.[2] The epidermis is the outermost layer, providing the initial barrier to the external environment. It is separated from the dermis by the basement membrane (basal lamina and reticular lamina). The epidermis contains melanocytes and gives color to the skin. The deepest layer of the epidermis also contains nerve endings. Beneath this, the dermis comprises two sections, the papillary and reticular layers, and contains connective tissues, vessels, glands, follicles, hair roots, sensory nerve endings, and muscular tissue.[3]

Between the integument and the deep body musculature there is a transitional subcutaneous zone made up of very loose connective and adipose tissue, the hypodermis. Substantial collagen bundles anchor the dermis to the hypodermis in a way that permits most areas of the skin to move freely over the deeper tissue layers.[4]

Epidermis

editThe epidermis is the strong, superficial layer that serves as the first line of protection against the outer environment. The human epidermis is composed of stratified squamous epithelial cells, which further break down into four to five layers: the stratum corneum, stratum granulosum, stratum spinosum and stratum basale. Where the skin is thicker, such as in the palms and soles, there is an extra layer of skin between the stratum corneum and the stratum granulosum, called the stratum lucidum. The epidermis is regenerated from the stem cells found in the basal layer that develop into the corneum. The epidermis itself is devoid of blood supply and draws its nutrition from its underlying dermis.[5]

Its main functions are protection, absorption of nutrients, and homeostasis. In structure, it consists of a keratinized stratified squamous epithelium; four types of cells: keratinocytes, melanocytes, Merkel cells, and Langerhans cells.

The predominant cell keratinocyte, which produces keratin, a fibrous protein that aids in skin protection, is responsible for the formation of the epidermal water barrier by making and secreting lipids.[6] The majority of the skin on the human body is keratinized, with the exception of the lining of mucous membranes, such as the inside of the mouth. Non-keratinized cells allow water to "stay" atop the structure.

The protein keratin stiffens epidermal tissue to form fingernails. Nails grow from a thin area called the nail matrix at an average of 1 mm per week. The lunula is the crescent-shape area at the base of the nail, lighter in color as it mixes with matrix cells. Only primates have nails. In other vertebrates, the keratinizing system at the terminus of each digit produces claws or hooves.[2]

The epidermis of vertebrates is surrounded by two kinds of coverings, which are produced by the epidermis itself. In fish and aquatic amphibians, it is a thin mucus layer that is constantly being replaced. In terrestrial vertebrates, it is the stratum corneum (dead keratinized cells). The epidermis is, to some degree, glandular in all vertebrates, but more so in fish and amphibians. Multicellular epidermal glands penetrate the dermis, where they are surrounded by blood capillaries that provide nutrients and, in the case of endocrine glands, transport their products.[7]

Dermis

editThe dermis is the underlying connective tissue layer that supports the epidermis. It is composed of dense irregular connective tissue and areolar connective tissue such as a collagen with elastin arranged in a diffusely bundled and woven pattern.

The dermis has two layers: the papillary dermis and the reticular layer. The papillary layer is the superficial layer that forms finger-like projections into the epidermis (dermal papillae),[5] and consists of highly vascularized, loose connective tissue. The reticular layer is the deep layer of the dermis and consists of the dense irregular connective tissue. These layers serve to give elasticity to the integument, allowing stretching and conferring flexibility, while also resisting distortions, wrinkling, and sagging.[3] The dermal layer provides a site for the endings of blood vessels and nerves. Many chromatophores are also stored in this layer, as are the bases of integumental structures such as hair, feathers, and glands.

Hypodermis

editThe hypodermis, otherwise known as the subcutaneous layer, is a layer beneath the skin. It invaginates into the dermis and is attached to the latter, immediately above it, by collagen and elastin fibers. It is essentially composed of a type of cell known as adipocytes, which are specialized in accumulating and storing fats. These cells are grouped together in lobules separated by connective tissue.

The hypodermis acts as an energy reserve. The fats contained in the adipocytes can be put back into circulation, via the venous route, during intense effort or when there is a lack of energy-providing substances, and are then transformed into energy. The hypodermis participates, passively at least, in thermoregulation since fat is a heat insulator.

Functions

editThe integumentary system has multiple roles in maintaining the body's equilibrium. All body systems work in an interconnected manner to maintain the internal conditions essential to the function of the body. The skin has an important job of protecting the body and acts as the body's first line of defense against infection, temperature change, and other challenges to homeostasis.[8][9]

Its main functions include:

- Protect the body's internal living tissues and organs

- Protect against invasion by infectious organisms

- Protect the body from dehydration

- Protect the body against abrupt changes in temperature, maintain homeostasis

- Help excrete waste materials through perspiration

- Act as a receptor for touch, pressure, pain, heat, and cold (see Somatosensory system)

- Protect the body against sunburns by secreting melanin

- Generate vitamin D through exposure to ultraviolet light

- Store water, fat, glucose, vitamin D

- Maintenance of the body form

- Formation of new cells from stratum germinativum to repair minor injuries

- Protect from UV rays.

- Regulates body temperature

- It distinguishes, separates, and protects the organism from its surroundings.

Small-bodied invertebrates of aquatic or continually moist habitats respire using the outer layer (integument). This gas exchange system, where gases simply diffuse into and out of the interstitial fluid, is called integumentary exchange.

Clinical significance

editPossible diseases and injuries to the human integumentary system include:

- Rash

- Yeast

- Athlete's foot

- Infection

- Sunburn

- Skin cancer

- Albinism

- Acne

- Herpes

- Herpes labialis, commonly called cold sores

- Impetigo

- Rubella

- Cancer

- Psoriasis

- Rabies

- Rosacea

- Atopic dermatitis

- Eczema

References

edit- ^ Martini, Frederic; Nath, Judi L. (2009). Fundamentals of anatomy & physiology (8th ed.). San Francisco: Pearson/Benjamin Cummings. p. 158. ISBN 978-0321505897.

- ^ a b Kardong, Kenneth V. (2019). Vertebrates : comparative anatomy, function, evolution (Eighth ed.). New York, NY. pp. 212–214. ISBN 978-1-259-70091-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b "The Ageing Skin – Part 1 – Structure of Skin". pharmaxchange.info. 4 March 2011.

- ^ Pratt, Rebecca. "Integument". AnatomyOne. Amirsys, Inc. Archived from the original on 2013-10-20. Retrieved 2012-09-28.

- ^ a b Kim, Joyce Y.; Dao, Harry (2022). "Physiology, Integument". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 32119273.

- ^ Yousef, Hani; Alhajj, Mandy; Sharma, Sandeep (2022). "Anatomy, Skin (Integument), Epidermis". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29262154.

- ^ Quay, Wilbur B. (1 February 1972). "Integument and the Environment Glandular Composition, Function, and Evolution". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 12 (1): 95–108.

- ^ Integumentary+System at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- ^ Marieb, Elaine; Hoehn, Katja (2007). Human Anatomy & Physiology (7th ed.). Pearson Benjamin Cummings. p. 142. ISBN 9780805359107.