In the economics study of the public sector, economic and social development is the process by which the economic well-being and quality of life of a nation, region, local community, or an individual are improved according to targeted goals and objectives.

The term has been used frequently in the 20th and 21st centuries, but the concept has existed in the West for far longer.[citation needed] "Modernization", "Westernization", and especially "industrialization" are other terms often used while discussing economic development. Historically, economic development policies focused on industrialization and infrastructure; since the 1960s, it has increasingly focused on poverty reduction.[1]

Whereas economic development is a policy intervention aiming to improve the well-being of people, economic growth is a phenomenon of market productivity and increases in GDP; economist Amartya Sen describes economic growth as but "one aspect of the process of economic development".

Definition and terminology

editThe precise definition of economic development has been contested: while economists in the 20th century viewed development primarily in terms of economic growth, sociologists instead emphasized broader processes of change and modernization.[2] Development and urban studies scholar Karl Seidman summarizes economic development as "a process of creating and utilizing physical, human, financial, and social assets to generate improved and broadly shared economic well-being and quality of life for a community or region".[3] Daphne Greenwood and Richard Holt distinguish economic development from economic growth on the basis that economic development is a "broadly based and sustainable increase in the overall standard of living for individuals within a community", and measures of growth such as per capita income do not necessarily correlate with improvements in quality of life.[4] The United Nations Development Programme in 1997 defined development as increasing people‟s choices. Choices depend on the people in question and their nation. The UNDP indicates four chief factors in development, especially human development, which are empowerment, equity, productivity, and sustainability.[5]

Mansell and Wehn state that economic development has been understood by non-practitioners since the World War II to involve economic growth, namely the increases in per capita income, and (if currently absent) the attainment of a standard of living equivalent to that of industrialized countries.[6][7] Economic development can also be considered as a static theory that documents the state of an economy at a certain place. According to Schumpeter and Backhaus (2003), the changes in this equilibrium state documented in economic theory can only be caused by intervening factors coming from the outside.[8]

History

editEconomic development originated in the post-war period of reconstruction initiated by the United States. In 1949, during his inaugural speech, President Harry Truman identified the development of undeveloped areas as a priority for the West:

- "More than half the people of the world are living in conditions approaching misery. Their food is inadequate, they are victims of the disease. Their economic life is primitive and stagnant. Their poverty is a handicap and a threat both to them and to more prosperous areas. For the first time in history, humanity possesses the knowledge and the skill to relieve the suffering of these people ... I believe that we should make available to peace-loving people the benefits of our store of technical knowledge to help them realize their aspirations for a better life… What we envisage is a program of development based on the concepts of democratic fair dealing ... Greater production is the key to prosperity and peace. And the key to greater production is a wider and more vigorous application of modem scientific and technical knowledge."

There have been several major phases of development theory since 1945. Alexander Gerschenkron argued that the less developed the country is at the outset of economic development (relative to others), the more likely certain conditions are to occur. Hence, all countries do not progress similarly.[9] From the 1940s to the 1960s the state played a large role in promoting industrialization in developing countries, following the idea of modernization theory. This period was followed by a brief period of basic needs development focusing on human capital development and redistribution in the 1970s. Neoliberalism emerged in the 1980s pushing an agenda of free trade and removal of import substitution industrialization policies.

In economics, the study of economic development was born out of an extension to traditional economics that focused entirely on the national product, or the aggregate output of goods and services. Economic development was concerned with the expansion of people's entitlements and their corresponding capabilities, such as morbidity, nourishment, literacy, education, and other socio-economic indicators.[10] Borne out of the backdrop of Keynesian economics (advocating government intervention), and neoclassical economics (stressing reduced intervention), with the rise of high-growth countries (Singapore, South Korea, Hong Kong) and planned governments (Argentina, Chile, Sudan, Uganda), economic development and more generally development economics emerged amidst these mid-20th century theoretical interpretations of how economies prosper.[11] Also, economist Albert O. Hirschman, a major contributor to development economics, asserted that economic development grew to concentrate on the poor regions of the world, primarily in Africa, Asia and Latin America yet on the outpouring of fundamental ideas and models.[12]

It has also been argued, notably by Asian and European proponents of infrastructure-based development, that systematic, long-term government investments in transportation, housing, education, and healthcare are necessary to ensure sustainable economic growth in emerging countries.

During Robert McNamara's 13 years at the World Bank, he introduced key changes, most notably, shifting the Bank's economic development policies toward targeted poverty reduction.[1] Before his tenure at the World Bank, poverty did not receive substantial attention as part of international and national economic development; the focus of development had been on industrialization and infrastructure.[1] Poverty also came to be redefined as a condition faced by people rather than countries.[1] According to Martha Finnemore, the World Bank under McNamara's tenure "sold" states poverty reduction "through a mixture of persuasion and coercion."[1]

Economic development goals

editThe development of a country has been associated with different concepts but generally encompasses economic growth through higher productivity,[13] political systems that represent as accurately as possible the preferences of its citizens,[14][15] The extension of rights to all social groups and the opportunities to get them[16] and the proper functionality of institutions and organizations that can attend more technically and logistically complex tasks (i.e. raise taxes and deliver public services).[17][18] These processes describe the State's capabilities to manage its economy, polity, society and public administration.[19] Generally, economic development policies attempt to solve issues in these topics.

With this in mind, economic development is typically associated with improvements in a variety of areas or indicators (such as literacy rates, life expectancy, and poverty rates), that may be causes of economic development rather than consequences of specific economic development programs. For example, health and education improvements have been closely related to economic growth, but the causality with economic development may not be obvious. In any case, it is important to not expect that particular economic development programs be able to fix many problems at once as that would be establishing unsurmountable goals for them that are highly unlikely they can achieved. Any development policy should set limited goals and a gradual approach to avoid falling victim to something Prittchet, Woolcock and Andrews call 'premature load bearing'.[19]

Many times the economic development goals of specific countries cannot be reached because they lack the State's capabilities to do so. For example, if a nation has little capacity to carry out basic functions like security and policing or core service delivery it is unlikely that a program that wants to foster a free-trade zone (special economic zones) or distribute vaccinations to vulnerable populations can accomplish their goals. This has been something overlooked by multiple international organizations, aid programs and even participating governments who attempt to carry out 'best practices' from other places in a carbon-copy manner with little success. This isomorphic mimicry –adopting organizational forms that have been successful elsewhere but that only hide institutional dysfunction without solving it on the home country –can contribute to getting countries stuck in 'capability traps' where the country does not advance in its development goals.[19] An example of this can be seen through some of the criticisms of foreign aid and its success rate at helping countries develop.[citation needed]

Beyond the incentive compatibility problems that can happen to foreign aid donations –that foreign aid granting countries continue to give it to countries with little results of economic growth[20] but with corrupt leaders that are aligned with the granting countries' geopolitical interests and agenda[21] –there are problems of fiscal fragility associated to receiving an important amount of government revenues through foreign aid. Governments that can raise a significant amount of revenue from this source are less accountable to their citizens (they are more autonomous) as they have less pressure to legitimately use those resources.[22] Just as it has been documented for countries with an abundant supply of natural resources such as oil,[23] countries whose government budget consists largely of foreign aid donations and not regular taxes are less likely to have incentives to develop effective public institutions.[22] This in turn can undermine the country's efforts to develop.

Economic development policies

editIn its broadest sense, policies of economic development encompass three major areas:

- Governments undertaking to meet broad economic objectives such as price stability, high employment, and sustainable growth. Such efforts include monetary and fiscal policies, regulation of financial institutions, trade, and tax policies.

- Programs that provide infrastructure and services such as highways, parks, affordable housing, crime prevention, and K–12 education.

- Job creation and retention through specific efforts in business finance, marketing, neighborhood development, workforce development, small business development, business retention and expansion,[24] technology transfer, and real estate development. This third category is a primary focus of economic development professionals.

Contractionary monetary policy is a tool used by central banks to slow down a country's economic growth. An example would be raising interest rates to decrease lending. In the United States, the use of contractionary monetary policy has increased women's unemployment.[25] Seguino and Heintz uses a panel dataset for each 50 states with unemployment, labor force participation by race, and annual labor market statistics. In addition, for contractionary monetary policy, they utilize the federal funds rate, the short-term interest rates charged to banks. Seguino and Heintz Seguino concludes that the impact of a one percentage point increase in the federal funds rate relative to white and black women's unemployment is 0.015 and 0.043, respectively[26]

One growing understanding in economic development is the promotion of regional clusters and a thriving metropolitan economy. In today's global landscape, location is vitally important and becomes a key in competitive advantage.[citation needed]

International trade and exchange rates are key issues in economic development. Currencies are often either under-valued or over-valued, resulting in trade surpluses or deficits. Furthermore, the growth of globalization has linked economic development with trends on international trade and participation in global value chains (GVCs) and international financial markets. The last financial crisis had a huge effect on economies in developing countries. Economist Jayati Ghosh states that it is necessary to make financial markets in developing countries more resilient by providing a variety of financial institutions. This could also add to financial security for small-scale producers.[27]

Organization

editEconomic development has evolved into a professional industry of highly specialized practitioners. The practitioners have two key roles: one is to provide leadership in policy-making, and the other is to administer policy, programs, and projects. Economic development practitioners generally work in public offices on the state, regional, or municipal level, or in public-private partnerships organizations that may be partially funded by local, regional, state, or federal tax money. These economic development organizations function as individual entities and in some cases as departments of local governments. Their role is to seek out new economic opportunities and retain their existing business wealth.

There are numerous other organizations whose primary function is not economic development that work in partnership with economic developers. They include the news media, foundations, utilities, schools, health care providers, faith-based organizations, and colleges, universities, and other education or research institutions.

Development indicators and indices

editThere are various types of macroeconomic and sociocultural indicators or "metrics" used by economists and geographers to assess the relative economic advancement of a given region or nation. The World Bank's "World Development Indicators" are compiled annually from officially recognized international sources and include national, regional and global estimates.[28]

GDP per capita and real income

editGDP per capita is gross domestic product divided by mid-year population. GDP is the sum of gross value added by all resident producers in the economy plus any product taxes and minus any subsidizes not included in the value of the products.[29] It is calculated without making deductions for depreciation of fabricated assets or for depletion and degradation of natural resources. Median income is related to real gross national income per capita and income distribution.

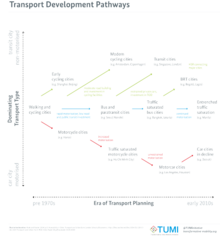

Modern transportation

editEuropean development economists have argued that the existence of modern transportation networks- such as high-speed rail infrastructure constitutes a significant indicator of a country's economic advancement: this perspective is illustrated notably through the Basic Rail Transportation Infrastructure Index (known as BRTI Index)[30] and related models such as the (Modified) Rail Transportation Infrastructure Index (RTI).[31]

Introduction of The GDI and GEM

editIn an effort to create an indicator that would help measure gender equality, the United Nations has created two measures: the Gender-Related Development Index (GDI) and the Gender Empowerment Measure (GEM). These indicators were first introduced in the 1995 UNDP Human Development Report.[32]

Other factors

editOther factors include the inflation rate, investment level and national debt, birth and death rates, life expectancy, morbidity, education levels (measured through literacy and numeracy rates), housing, social services like hospitals, health facilities, clean and safe drinking water, schools (measured by the distance learners must travel to reach them), ability to use hard infrastructure (railways, roads, ports, airports, harbours, etc.), and telecommunications and other soft infrastructure like the Internet.[5]

Gender Empowerment Measure

editThe Gender Empowerment Measure (GEM) focuses on aggregating various indicators that focus on capturing the economic, political, and professional gains made by women. The GEM is composed of just three variables: income earning power, share in professional and managerial jobs, and share of parliamentary seats.[33]

Gender Development Index

editThe Gender Development Index (GDI) measures the gender gap in human development achievements. It takes the disparity between men and women into account through three variables, health, knowledge, and living standards.[34]

See also

edit- Constitutional economics

- Critical juncture theory

- Commerce

- Democracy and economic growth

- Development finance institution

- European Free Trade Association

- European Union

- Education

- Economics

- Financial deepening

- Gender and development

- Green Development

- Infrastructure

- International development

- International Monetary Fund

- Local Economic Development

- North–South divide

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- Private sector development

- Socioeconomics

- United Nations Development Program

- Universities

- World Bank Group

References

edit- ^ a b c d e Finnemore, Martha (1996). National Interests in International Society. Cornell University Press. pp. 89–97. ISBN 978-0-8014-8323-3. JSTOR 10.7591/j.ctt1rv61rh.

- ^ Jaffee, David (1998). Levels of Socio-economic Development Theory. Westport and London: Praeger. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-275-95658-5.

- ^ Seidman, Karl F. (2005). Economic Development Finance. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-7656-2817-6.

- ^ Greenwood, Daphne T.; Holt, Richard P. F. (2010). Local Economic Development in the 21st Century. Armonk and London: M. E. Sharpe. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-0-7656-2817-6.

- ^ a b Economic development and change in Tanzania since independence

- ^ "Telecommunications and Social Development: The Meaning of Development, Sustainable Development and Rural Development". Macro Environment and Telecommunications. Archived from the original on 2010-01-30. Retrieved 2009-10-14.

- ^ Mansell, R & and Wehn, U. 1998. Knowledge Societies: Information Technology for Sustainable Development. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Schumpeter, Joseph & Backhaus, Ursula, 2003. The Theory of Economic Development. In Joseph Alois Schumpeter. pp. 61–116. doi:10.1007/0-306-48082-4_3

- ^ Gerschenkron, Alexander (1962). Economic Backwardness in Historical Perspective. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- ^ See Michael Todaro and Stephen C. Smith, "Economic Development" (11th ed.). Archived from the original on 2018-06-23. Retrieved 2012-03-30., Pearson Education and Addison-Wesley (2011).

- ^ Sen, A (1983). "Development: Which Way Now?". Economic Journal. 93 (372): 745–62. doi:10.2307/2232744. JSTOR 2232744.

- ^ Hirschman, A. O. (1981). The Rise and Decline of Development Economics. Essays in Trespassing: Economics to Politics to Beyond. pp. 1–24

- ^ Simon Kuznets (1966). Modern Economic Growth: Rate, Structure and Spread, Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut.

- ^ Kenneth Shepsle and Mark Bonchek (2010), Analyzing Politics, Second Edition, Norton, pp. 67 – 86.

- ^ G. Bingham Powell (2000). Elections as Instruments of Democracy: Majoritarian and Proportional Views. Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut.

- ^ C.A. Bayly (2008). "Indigenous and Colonial Origins of Comparative Economic Development: The Case of Colonial India and Africa", Policy Research Working Paper 4474, The World Bank.

- ^ Deborah Bräutigam (2002), "Building Leviathan: Revenue, State Capacity and Governance", IDS Bulletin 33, no. 3, pp. 1 – 17

- ^ Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson (2012), Why Nations Fail, New York: Crown Business.

- ^ a b c Lant Pritchett, Michael Woolcock & Matt Andrews (2013). Looking Like a State: Techniques of Persistent Failure in State Capability for Implementation, The Journal of Development Studies, 49:1, 1–18, DOI: 10.1080/00220388.2012.709614

- ^ William Easterly (2003), "Can Foreign Aid Buy Growth?" in Journal of Economic Perspectives 17(3), pp. 23 – 48.

- ^ Ethan Bueno de Mesquita (2016), Political Economy for Public Policy, Princeton University Press, chapter 11.

- ^ a b Todd Moss, Gunilla Pettersson and Nicolas van de Walle (2006), "An Aid Institutions Paradox? A review essay on aid dependency and State building in Sub-Saharan Africa", Working Paper 74, Center for Global Development.

- ^ Michael Ross (2012), The Oil Curse: How petroleum wealth shapes the development of nations.

- ^ "What is BR&E?". Business Retention and Expansion International. 2018-10-23. Retrieved 2019-01-09.

- ^ Seguino, Stephanie (2019-05-28). "Engendering Macroeconomic Theory and Policy". Feminist Economics. 26 (2): 27–61. doi:10.1080/13545701.2019.1609691. hdl:10986/28951. ISSN 1354-5701. S2CID 158543241.

- ^ Seguino, Stephanie; Heintz, James (July 2012). "Monetary Tightening and the Dynamics of US Race and Gender Stratification". American Journal of Economics and Sociology. 71 (3): 603–638. doi:10.1111/j.1536-7150.2012.00826.x. ISSN 0002-9246.

- ^ Jayati Gosh (January 17, 2013). "Too much of the same". D+C. Archived from the original on Oct 5, 2023.

- ^ "World Development Indicators". DataBank. Retrieved 2020-12-01.

- ^ Callen, Tim. "Gross Domestic Product: An Economy's All". International Monetary Fund. Archived from the original on 2012-02-17.

- ^ Firzli, M. Nicolas J. (September 2013). "Transportation Infrastructure and Country Attractiveness". Revue Analyse Financière. Paris. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ^ M. Nicolas J. Firzli : '2014 LTI Rome Conference: Infrastructure-Driven Development to Conjure Away the EU Malaise?', Revue Analyse Financière, Q1 2015 – Issue N°54

- ^ United Nations Development Programme (1995). Human development report 1995. New York: Oxford University Press for the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). ISBN 978-0-19-510023-5. OCLC 33420816.

- ^ United Nations Development Programme (1995). Human development report 1995. New York: Oxford University Press for the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). ISBN 978-0-19-510023-5. OCLC 33420816.

- ^ Nations, United. "Gender Development Index (GDI) | Human Development Reports". hdr.undp.org. Retrieved 2019-12-19.

Further reading

edit- Spolaore, Enrico; Wacziarg, Romain (2013). "How Deep Are the Roots of Economic Development?" (PDF). Journal of Economic Literature. 51 (2): 325–369. doi:10.1257/jel.51.2.325.

- Gorodnichenko, Yuriy; Roland, Gerard (2017). "Culture, Institutions, and the Wealth of Nations". The Review of Economics and Statistics. 99 (3): 402–416. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00599. hdl:2027.42/78010.

- Nunn, Nathan (2020). "The historical roots of economic development". Science. 367 (6485). doi:10.1126/science.aaz9986. PMID 32217703. S2CID 214671144.

- Yuen Ang, Yuen (2024). "Adaptive Political Economy: Toward a New Paradigm". World Politics.