Anti-miscegenation laws in the United States

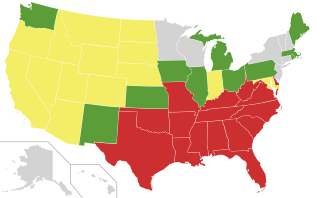

In the United States, many U.S. states historically had anti-miscegenation laws which prohibited interracial marriage and, in some states, interracial sexual relations. Some of these laws predated the establishment of the United States, and some dated to the later 17th or early 18th century, a century or more after the complete racialization of slavery.[1] Nine states never enacted anti-miscegenation laws, and 25 states had repealed their laws by 1967. In that year, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Loving v. Virginia that such laws are unconstitutional under the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.[2][3]

The term miscegenation was first used in 1863, during the American Civil War, by journalists to discredit the abolitionist movement by stirring up debate over the prospect of interracial marriage after the abolition of slavery.[4]

Typically defining mixed-race marriages or sexual relations as a felony, these laws also prohibited the issuance of marriage licenses and the solemnization of weddings between mixed-race couples and prohibited the officiation of such ceremonies. Sometimes, the individuals attempting to marry would not be held guilty of miscegenation itself, but felony charges of adultery or fornication would be brought against them instead. All anti-miscegenation laws banned marriage between whites and non-white groups, primarily black people, but often also Native Americans and Asian Americans.[5]

In many states, anti-miscegenation laws also criminalized cohabitation and sex between whites and non-whites. In addition, Oklahoma in 1908 banned marriage "between a person of African descent" and "any person not of African descent"; Louisiana in 1920 banned marriage between Native Americans and African Americans (and from 1920 to 1942, concubinage as well); and Maryland in 1935 banned marriages between black people and Filipinos.[6] While anti-miscegenation laws are often regarded as a Southern phenomenon, most states of the Western United States and the Great Plains also enacted them.

Although anti-miscegenation amendments were proposed in the United States Congress in 1871, 1912–1913, and 1928,[7][8] a nationwide law against mixed-race marriages was never enacted. Prior to the California Supreme Court's ruling in Perez v. Sharp (1948), no court in the United States had ever struck down a ban on interracial marriage. In 1967, the United States Supreme Court (the Warren Court) unanimously ruled in Loving v. Virginia that anti-miscegenation laws are unconstitutional. After Loving, the remaining state anti-miscegenation laws were repealed; the last state to repeal its laws against interracial marriage was Alabama in 2000.

Colonial era

editThe first laws which criminalized marriages and sexual relations between whites and non-whites were enacted in the colonial era in the colonies of Virginia and Maryland, which depended economically on slavery.[9]

At first, in the 1660s, the first laws in Virginia and Maryland regulating marriage between whites and black people only pertained to the marriages of whites to black (and mulatto) enslaved people and indentured servants. In 1664, Maryland criminalized such marriages—the 1681 marriage of Irish-born Nell Butler to an enslaved African man was an early example of the application of this law. The Virginian House of Burgesses passed a law in 1691 forbidding free black people and whites to intermarry, followed by Maryland in 1692. This was the first time in American history that a law was invented that restricted access to marriage partners solely on the basis of "race", not class or condition of servitude.[10] Later these laws also spread to colonies with fewer enslaved and free black people, such as Pennsylvania and Massachusetts. Moreover, after the independence of the United States had been established, similar laws were enacted in territories and states which outlawed slavery.[citation needed]

A sizable number of the indentured servants in the Thirteen Colonies were brought over from the Indian subcontinent by the East India Company.[11] Anti-miscegenation laws discouraging interracial marriage between White Americans and non-whites affected South Asian immigrants as early as the 17th century.[citation needed] For example, a Eurasian daughter born to an Indian father and Irish mother in Maryland in 1680 was classified as a "mulatto" and sold into slavery.[11] Anti-miscegenation laws there continued into the early 20th century. For example, the Bengali revolutionary Tarak Nath Das's white American wife, Mary Keatinge Morse, was stripped of her American citizenship for her marriage to an "alien ineligible for citizenship."[11] In 1918, there was considerable controversy in Arizona when an Indian farmer B. K. Singh married the sixteen-year-old daughter of one of his white tenants.[12]

In 1685, the French government issued a special Code Noir restricted to colonial Louisiana, which forbade marriage between Catholics and non-Catholics in that colony.[13] However, interracial cohabitation and interracial sex were never prohibited in French Louisiana (see plaçage). The situation of the children (free or enslaved) followed the situation of the mother.[14] Under Spanish rule, interracial marriage was possible with parental consent under the age of 25 and without it when the partners were older. In 1806, three years after the U.S. gained control over the state, interracial marriage was once again banned.[15]

Jacqueline Battalora [16] argues that the first laws banning all marriage between whites and black people, enacted in Virginia and Maryland, were a response by the planter elite to the problems they were facing due to the socio-economic dynamics of the plantation system in the Southern colonies. The bans in Virginia and Maryland were established at a time when slavery was not yet fully institutionalized. At the time, most forced laborers on the plantations were indentured servants, and they were mostly European. Some historians have suggested that the at-the-time unprecedented laws banning "interracial" marriage were originally invented by planters as a divide-and-rule tactic after the uprising of European and African indentured servants in cases such as Bacon's Rebellion. According to this theory, the ban on interracial marriage was issued to split up the ethnically mixed, increasingly "mixed-race" labor force into "whites", who were given their freedom, and "blacks", who were later treated as slaves rather than as indentured servants. By outlawing "interracial" marriage, it became possible to keep these two new groups separated and prevent a new rebellion.

After independence

editIn 1776, seven of the Thirteen Colonies enforced laws against interracial marriage. Although slavery was gradually abolished in the North after independence, this at first had little impact on the enforcement of anti-miscegenation laws. An exception was Pennsylvania, which repealed its anti-miscegenation law in 1780, together with some of the other restrictions placed on free Black people, when it enacted a bill for the gradual abolition of slavery in the state.

The Quaker planter and slave trader Zephaniah Kingsley, Jr. publicly advocated, and personally practiced, racial mixing as a way toward ending slavery, as well as a way to produce healthier and more beautiful offspring. These views were tolerated in Spanish Florida, where free people of color had rights and could own and inherit property. After Florida became a U.S. territory in 1821, he moved with his wives, children, and the people he enslaved, to Haiti.[17]

Another case of interracial marriage was Andrea Dimitry and Marianne Céleste Dragon, a free woman of African and European ancestry. Such marriages gave rise to a large creole community in New Orleans. She was listed as white on her marriage certificate. Marianne's father, Don Miguel Dragon, and mother, Marie Françoise Chauvin Beaulieu de Monpliaisir, also married in New Orleans Louisiana around 1815. Marie Françoise was a woman of African ancestry. Marie Françoise Chauvin de Beaulieu de Montplaisir and her mother Marianne Lalande were originally slaves belonging to Mr. Charles Daprémont de La Lande, a member of the Superior Council.[18]

For the radical abolitionists who organized to oppose slavery in the 1830s, laws banning interracial marriage embodied the same racial prejudice that they saw at the root of slavery. Abolitionist leader William Lloyd Garrison took aim at Massachusetts' legal ban on interracial marriage as early as 1831. Anti-abolitionists defended the measure as necessary to prevent racial amalgamation and to maintain the Bay State's proper racial and moral order. Abolitionists, however, objected that the law, because it distinguished between "citizens on account of complexion" and violated the broad egalitarian tenets of Christianity and republicanism as well as the state constitution's promise of equality. Beginning in the late 1830s, abolitionists began a several-year petition campaign that prompted the legislature to repeal the measure in 1843. Their efforts—both tactically and intellectually—constituted a foundational moment in the era's burgeoning minority-rights politics, which would continue to expand into the 20th century.[19] As the U.S. expanded, however, all the new slave states as well as many new free states such as Illinois[20] and California[21] enacted such laws.

While opposed to slavery, in a speech in Charleston, Illinois in 1858, Abraham Lincoln stated, "I am not, nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people".[22]

Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, Texas, South Carolina, and Alabama legalized interracial marriage for some years during the Reconstruction period. Anti-miscegenation laws rested unenforced, were overturned by courts or repealed by the state government (in Arkansas[23] and Louisiana[24]). However, after white Democrats took power in the South during "Redemption", anti-miscegenation laws were re-enacted and once more enforced, and in addition Jim Crow laws were enacted in the South which also enforced other forms of racial segregation.[25][not specific enough to verify]

In the 1870s and 1880s, the state of Tennessee repeatedly prosecuted and incarcerated David Galloway and Malinda Brandon for their interracial marriage.[26] Tennessee Republicans passed a resolution supporting Galloway's right to marry at their 1874 political convention.[27] In Florida, the new Constitution of 1885 prohibited marriage between "a white person and a person of negro descent" (Article XVI, Section 24).[28]

The first anti miscegenation law in Oregon was passed in 1866. It stated that "all marriages of white persons with Negroes, Chinamen, or mulattoes are void, and are prohibited," effectively prohibiting interracial marriages involving African Americans, Chinese individuals, and individuals of mixed race.[29] Oregon's miscegenation laws specifically prohibited marriages between white individuals and individuals of "Mongolian" or Asian descent.[29] These laws aimed to reflect the prevailing racial prejudices and discriminatory attitudes of the time.

In 1909, Aoki and Helen Emery, an interracial couple were denied a marriage license in California due to laws prohibiting marriage between Japanese and Caucasian individuals.[30] They then traveled to Portland, Oregon, hoping to obtain a marriage license there but were again denied based on similar racial restrictions.[30]

A number of northern and western states permanently repealed their anti-miscegenation laws during the 19th century. This, however, did little to halt anti-miscegenation sentiments in the rest of the country.

Newly established western states continued to enact laws banning interracial marriage in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Between 1913 and 1948, 30 out of the then 48 states enforced anti-miscegenation laws. Only Connecticut, New Hampshire, New York, New Jersey, Vermont, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Alaska, Hawaii, and Washington, D.C. never enacted them.[31]

High court decisions, 1883-1954

editThe constitutionality of anti-miscegenation laws was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in the 1883 case Pace v. Alabama (106 U.S. 583). The Supreme Court ruled that the Alabama anti-miscegenation statute did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. According to the court, both races were treated equally, because whites and black people were punished in equal measure for breaking the law against interracial marriage and interracial sex.

In State v. Pass,[32][33] the Supreme Court of Arizona rejected an appeal by Frank Pass of a murder conviction based on the testimony of his wife Ruby Contreras Pass against him, on the grounds that their marriage was illegal since Pass was partly Mexican and native American and Contreras was white. Interpreting the state's anti-miscegenation statute, the court ruled that persons of mixed racial heritage could not legally marry anyone. The court recognized that the result was absurd and expressed the hope that the legislature would amend the statute. In a deviation from anti-miscegenation laws and interpretations in other states, the court appeared to treat Hispanics/ Mexicans as separate from "Caucasian" or white, though "French" and "Spanish" ethnicities were also referred to as distinct "races".

In 1954, Linnie Jackson was sentenced to five years in prison for marrying a white man, A.C. Burcham. This decision was affirmed by the Supreme Court of Alabama. Jackson appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States, which noted that the law was likely unconstitutional, but a clerk suggested that "action might be postponed until the school segregation problem is solved." The court refused certiorari and Jackson served five years in prison.[34]

Repeal of anti-miscegenation laws, 1948–1967

editIn 1948, the California Supreme Court ruled in Perez v. Sharp (1948) that the Californian anti-miscegenation laws violated the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, the first time since Reconstruction that a state court declared such laws unconstitutional, and making California the first state since Ohio in 1887 to overturn its anti-miscegenation law.

The case raised constitutional questions in states which had similar laws, which led to the repeal or overturning of such laws in fourteen states by 1967. Sixteen states, mainly Southern states, were the exception. In any case, in the 1950s, the repeal of anti-miscegenation laws was still a controversial issue in the U.S., even among supporters of racial integration.

In a 1949 essay, following Perez Vs. Sharp, Edward T. Wright noted eight states where anti-miscegenation laws specified penalties of a year or more in prison, including a provision in Virginia law of "one year in the penitentiary for any Negro registering as a white". Wright noted that interracial marriage remained uncommon and widely disapproved of in Northern states where it was legal, in contrast to widespread fears of "amalgamation" in the South.

He observed that such laws existed even where there was little chance of such marriages:

- "Though many states which have 'miscegenation laws' have a large population of members of the race prohibited from marrying whites, there are many states which do not."

Furthermore, looking at the extent of pre-marital blood tests for venereal disease, he noted:

- "(T)he worst offenders of the states failing to protect their citizens with a good health law are the very states which insist they must protect the health of their citizens by prohibiting interracial marriage."

Wright suggested these laws were ineffective even in terms of preventing mixed-race births:

- "There might, in fact, be fewer mulatto children if white men having illicit intercourse with Negro women knew they could no longer rest behind a law which said the woman or offspring can acquire none of the rights ordinarily afforded by the law of domestic relations... (I)f the purpose of the laws surveyed has been to prevent inter mixture of blood, it is well to conclude that they have failed to fulfill this purpose."[35]

Political theorist Hannah Arendt was a Jewish refugee from Nazi Germany, who escaped from Europe during the Holocaust.[36] In 1958, she published Reflections on Little Rock, an essay in response to the 1957 Little Rock Crisis. Arendt asserted that anti-miscegenation laws were an even deeper injustice than the racial segregation of public schools. The free choice of a spouse, she argued, was "an elementary human right":

- "Even political rights, like the right to vote, and nearly all other rights enumerated in the Constitution, are secondary to the inalienable human rights to 'life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness' proclaimed in the Declaration of Independence; and to this category the right to home and marriage unquestionably belongs."

Arendt was severely criticized by fellow liberals, who feared that her essay would alarm racist whites and thus hinder the civil rights movement. Commenting on the Supreme Court's ruling in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka against de jure racial segregation in public schools, Arendt argued that anti-miscegenation laws were more basic to white supremacy than racial segregation in education.

Arendt's analysis echoed the conclusions of Gunnar Myrdal. In his essay Social Trends in America and Strategic Approaches to the Negro Problem (1948), Myrdal ranked the social areas where restrictions were imposed by Southern whites on African Americans from the least to the most important: jobs, courts and police, politics, basic public facilities, "social equality" including dancing and handshaking, and most importantly, marriage. His ranking matched the order in which segregation later fell. First, legal segregation in the armed forces, then segregation in education and in basic public services, then restrictions on the voting rights of African-Americans. These victories were ensured by the Civil Rights Act of 1964. But the bans on interracial marriage were the last to go, in 1967.

Most Americans in the 1950s were opposed to interracial marriage and did not see laws banning interracial marriage as an affront to the principles of American democracy. A 1958 Gallup poll showed that 94% of Americans disapproved of interracial marriage.[37] When former president Harry S. Truman was asked by a reporter in 1963 if interracial marriage would become widespread in the U.S., he responded, "I hope not; I don’t believe in it", before asking, "Would you want your daughter to marry a Negro? She won't love someone who isn't her color."[38]

Attitudes towards bans on interracial marriage began to change in the 1960s. Civil rights organizations were helping interracial couples who were being penalized for their relationships to take their cases to the U.S. Supreme Court. Since Pace v. Alabama (1883), the U.S. Supreme Court had declined to make a judgment in such cases. But in 1964, the Warren Court decided to issue a ruling in the case of an interracial couple from Florida who had been convicted because they had been cohabiting. In McLaughlin v. Florida, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Florida state law which prohibited cohabitation between whites and non-whites was unconstitutional and based solely on a policy of racial discrimination. However, the court did not rule on Florida's ban on marriage between whites and non-whites, despite the appeal of the plaintiffs to do so and the argument made by the state of Florida that its ban on cohabitation between whites and blacks was ancillary to its ban on marriage between whites and blacks. However, in 1967, the court did decide to rule on the remaining anti-miscegenation laws when it was presented with the case of Loving v. Virginia.

Loving v. Virginia

editIn 1967, an interracial couple, Richard and Mildred Loving, successfully challenged the constitutionality of the ban on interracial marriage in Virginia. Their case reached the U.S. Supreme Court as Loving v. Virginia.

In 1958, the Lovings married in Washington, D.C. to evade Virginia's anti-miscegenation law (the Racial Integrity Act). On their return to Virginia, they were arrested in their bedroom for living together as an interracial couple. The judge suspended their sentence on the condition that the Lovings leave Virginia and not return for 25 years. In 1963, the Lovings, who had moved to Washington, D.C., decided to appeal this judgment. In 1965, Virginia trial court Judge Leon Bazile, who heard their original case, refused to reconsider his decision. Instead, he defended racial segregation, writing:

Almighty God created the races white, black, yellow, Malay, and red, and placed them on separate continents, and but for the interference with his arrangement there would be no cause for such marriages. The fact that he separated the races shows that he did not intend the races to mix.[39]

The Lovings then took their case to the Supreme Court of Virginia, which invalidated the original sentence but upheld the state's Racial Integrity Act. Finally, the Lovings turned to the U.S Supreme Court. The court, which had previously avoided taking miscegenation cases, agreed to hear an appeal. In 1967, 84 years after Pace v. Alabama in 1883, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that the anti-miscegenation laws were unconstitutional.[2][3] Chief Justice Warren wrote in the court majority opinion that:[2][3]

Marriage is one of the "basic civil rights of man", fundamental to our very existence and survival ... To deny this fundamental freedom on so unsupportable a basis as the racial classifications embodied in these statutes, classifications so directly subversive of the principle of equality at the heart of the Fourteenth Amendment, is surely to deprive all the State's citizens of liberty without due process of law. The Fourteenth Amendment requires that the freedom of choice to marry not be restricted by invidious racial discriminations. Under our Constitution, the freedom to marry, or not to marry, a person of another race resides with the individual and cannot be infringed by the State.

The U.S. Supreme Court condemned Virginia's anti-miscegenation law as "designed to maintain White Supremacy".

Later events

editIn 1967, 17 Southern states plus Oklahoma still enforced laws prohibiting marriage between whites and non-whites. Maryland repealed its law at the start of Loving v. Virginia in the Supreme Court.

After the Supreme Court ruling declaring such laws to be unconstitutional, the laws in the remaining 16 states ceased to be enforceable. Even so, it was necessary for the Supreme Court of Florida to issue a writ of mandamus in order to compel a Dade County judge to issue a marriage license to an interracial couple. Two Justices of the court dissented from the issuance of the writ.[40] Besides removing such laws from their statute books, a number of state constitutions were also amended to remove language prohibiting miscegenation: Florida in 1969, Mississippi in 1987, South Carolina in 1998, and Alabama in 2000. In the respective referendums, 52% of voters in Mississippi, 62% of voters in South Carolina and 59% of voters in Alabama voted in favor of the amendments. In Alabama, nearly 526,000 people voted against the amendment, including a majority of voters in some rural counties.[41][42][43][44]

Three months after Loving v. Virginia, "Storybook Children" sung by Billy Vera and Judy Clay became the first romantic interracial duet to chart in the U.S.[45]

In 2009, Keith Bardwell, a justice of the peace in Robert, Louisiana, refused to officiate a civil wedding for an interracial couple. A nearby justice of the peace, on Bardwell's referral, officiated the wedding; the interracial couple sued Keith Bardwell and his wife Beth Bardwell in federal court.[46][47] After facing wide criticism for his actions, including from Louisiana Governor Bobby Jindal, Bardwell resigned on November 3, 2009.[48]

As of January 24, 2024[update], three states still require couples to declare their racial background when applying for a marriage license, without which they cannot marry. The states are Kentucky, Louisiana, and New Hampshire.[49] In 2019, a Virginia law that required partners to declare their race on marriage applications was challenged in court.[50] Within a week the state's Attorney-General directed that the question is to become optional,[51] and in October 2019, a U.S. District judge ruled the practice unconstitutional and barred Virginia from enforcing the requirement.[52]

In 2016, Mississippi passed a law to protect "sincerely held religious beliefs or moral convictions".[53] In September 2019, an owner of a wedding venue in Mississippi refused to allow a mixed-race wedding to take place in the venue, claiming the refusal was based on her Christian beliefs. After an outcry on social media and after consulting with her pastor, the owner apologized to the couple.[54]

Summary

editRepealed before Loving v. Virginia

Repealed after Loving v. Virginia

Anti-miscegenation laws repealed through 1887

edit| State | First law passed | Law repealed | Races white people were banned from marrying | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illinois | 1829 | 1874 | Blacks | |

| Iowa | 1839 | 1851 | Blacks | Not formally repealed; rather, the legislature quietly left that Territorial provision out of its first "Code of Iowa" (1851) after it became a state.[55] |

| Kansas | 1855 | 1859 | Blacks | Law repealed before reaching statehood |

| Maine | 1821 | 1883 | Blacks, Native Americans | |

| Massachusetts | 1705 | 1843 | Black, Native Americans | Passed the 1913 law preventing out-of-state couples from circumventing their home-state anti-miscegenation laws, which itself was repealed on July 31, 2008 |

| Michigan | 1838 | 1883 | Blacks | |

| New Mexico | 1857 | 1866 | Blacks | Law repealed before reaching statehood |

| Ohio | 1861 | 1887 | Blacks | Last state to repeal its anti-miscegenation law before California did so in 1948 |

| Pennsylvania | 1725 | 1780 | Blacks | |

| Rhode Island | 1798 | 1881 | Blacks, Native Americans | |

| Washington | 1855 | 1868 | Blacks, Native Americans | Law repealed before reaching statehood |

Anti-miscegenation laws repealed 1948–1967

edit| State | First law passed | Law repealed | Races white people were banned from marrying | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona | 1865 | 1962 | Blacks, Asians, Filipinos, Indians | Filipinos ("Malays") and Indians ("Hindus") added to list of "races" in 1931. As interpreted by the Supreme Court of Arizona in State v. Pass, 59 Ariz. 16, 121 P.2d 882 (1942), the law prohibited persons of mixed racial heritage from marrying anyone. |

| California | 1850 | 1948 | Blacks, Asians, Filipinos | Until Roldan v. Los Angeles County, it was unclear whether the law applied to Filipinos.[56] Anti-miscegenation law overturned by state judiciary in Supreme Court of California case Perez v. Sharp. Most Hispanics were included in White category. |

| Colorado | 1864 | 1957 | Blacks | |

| Idaho | 1864 | 1959 | Blacks, Asians | |

| Indiana | 1818 | 1965 | Blacks | Indiana was the first state to make interracial marriage a felony.[57] The 1818 statute that made marriage between Black and white individuals in the state illegal was updated with legislation in 1840, which made any marriage between Black and white individuals in Indiana "null and void."[58] |

| Maryland | 1692 | 1967 | Blacks, Filipinos | Repealed its law in response to the start of the Loving v. Virginia case, and was the last state to repeal its law before the Supreme Court made all such laws unenforceable. Maryland also was one of the states to ban marriages between some peoples of color, preventing black–Filipino marriages in addition to Filipino–white and black–white marriages. |

| Montana | 1909 | 1953 | Blacks, Asians | |

| Nebraska | 1855 | 1963 | Blacks, Asians | |

| Nevada | 1861 | 1959 | Blacks, Native Americans, Asians, Filipinos | On December 11, 1958, a court order struck down the law forbidding marriage between Harry Bridges and Noriko Sawada, citing the California case Perez v. Sharp and declaring such laws infringements on the basic principles of freedom. |

| North Dakota | 1909 | 1955 | Blacks | |

| Oregon | 1862 | 1951 | Blacks, Native Americans, Asians, Native Hawaiians | |

| South Dakota | 1909 | 1957 | Blacks, Asians, Filipinos | |

| Utah | 1852 | 1963 | Blacks, Asians, Filipinos | Initially enacted via the Act in Relation to Service |

| Wyoming | 1913 | 1965 | Blacks, Asians, Filipinos | As a territory, Wyoming banned interracial marriage in 1869. This law was repealed in 1882 prior to statehood, but a new ban was enacted after statehood in 1913.[59] |

Anti-miscegenation laws overturned on June 12, 1967, by Loving v. Virginia

edit| State | First law passed | Law repealed[60] | Races white people were banned from marrying | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 1822 | 2000 (constitution) | Blacks | Repealed during Reconstruction, law later reinstated |

| Arkansas | 1838 | 1973 | Blacks | Repealed during Reconstruction, law later reinstated |

| Delaware | 1807 | 1974 (omission) 1986 (repeal) |

Blacks | [61] |

| Florida | 1832 | 1969 | Blacks | Repealed during Reconstruction, law later reinstated (note law reinstated banning just blacks) |

| Georgia | 1750 | 1972 | Blacks, Native Americans, Filipinos | |

| Kentucky | 1792 | 1974 | Blacks | repealed during reconstruction in 1868 reinstated in 1894 |

| Louisiana | 1724 | 1972, 1975 | Blacks, Filipinos | Repealed during Reconstruction in 1868, law later reinstated in 1910[62] |

| Mississippi | 1822 | 1987 (constitution) | Blacks, Asians | Repealed during Reconstruction under the 1868 constitution, law later reinstated by the 1890 constitution. |

| Missouri | 1835 | 1969 | Blacks, Asians | |

| North Carolina | 1715 | 1970 (constitution) 1973 (law) |

Blacks | Starting in 1887, North Carolina also prevented marriages between Blacks and "Croatan Indians", but all other marriages between people of color were not covered by legislation |

| Oklahoma | 1897 | 1969 | Blacks | Oklahoma's law was unique in its phrasing, preventing marriages of "any person of African descent ... to any person not of African descent." This statute was invoked occasionally to void marriages between blacks and Native Americans.[63] |

| South Carolina | 1717 | 1970, 1972 (law) 1998 (constitution) |

Blacks, Native Americans, Indians | Repealed during Reconstruction, law later reinstated in 1879 |

| Tennessee | 1741[citation needed] | 1978 | Blacks | |

| Texas | 1837 | 1969 | All non-whites | |

| Virginia | 1691 | 1968 | All non-whites | Previous anti-miscegenation law made more severe by Racial Integrity Act of 1924 |

| West Virginia | 1863 | 1969 | Blacks |

Proposed constitutional amendments

editAt least three attempts have been made to amend the U.S. Constitution to bar interracial marriage in the country.[64]

- In 1871, Representative Andrew King, a Democrat of Missouri, proposed a nationwide ban on interracial marriage. King proposed the amendment because he feared that the Fourteenth Amendment, ratified in 1868 to give ex-slaves citizenship (the Freedmen) as part of the process of Reconstruction, would someday render laws against interracial marriage unconstitutional, as it eventually did.

- In December 1912 and January 1913, Representative Seaborn Roddenbery, a Democrat of Georgia, introduced a proposal in the House of Representatives to insert a prohibition of miscegenation into the US Constitution. According to the wording of the proposed amendment, "Intermarriage between Negroes or persons of color and Caucasians... within the United States... is forever prohibited." Roddenbery's proposal was more severe because it defined the racial boundary between whites and "persons of color" by applying the one-drop rule. In his proposed amendment, anyone with "any trace of African or Negro blood" was banned from marrying a white spouse.

- Roddenbery's proposed amendment was a direct reaction to African American heavyweight boxer Jack Johnson's marriages to white women, first to Etta Duryea and then to Lucille Cameron. In 1908, Johnson had become the first black boxing world champion, having beaten Tommy Burns. After his victory, the search was on for a white boxer, a "Great White Hope", to beat Johnson. Those hopes were dashed in 1910, when Johnson beat former world champion Jim Jeffries. This victory ignited race riots across America as frustrated whites attacked celebrating African Americans.[65] Johnson's marriages to and affairs with white women infuriated some Americans, mostly white. In his speech introducing his bill before the United States Congress, Roddenbery compared the marriage of Johnson and Cameron to the enslavement of white women, and warned of future civil war that would ensue if interracial marriage was not made illegal nationwide:

No brutality, no infamy, no degradation in all the years of southern slavery, possessed such villainous character and such atrocious qualities as the provision of the laws of Illinois, Massachusetts, and other states which allow the marriage of the Negro, Jack Johnson, to a woman of Caucasian strain. [Applause]. Gentleman, I offer this resolution ... that the States of the Union may have an opportunity to ratify it. ... Intermarriage between whites and blacks is repulsive and averse to every sentiment of pure American spirit. It is abhorrent and repugnant to the very principles of Saxon government. It is subversive of social peace. It is destructive of moral supremacy, and ultimately this slavery of white women to black beasts will bring this nation a conflict as fatal as ever reddened the soil of Virginia or crimsoned the mountain paths of Pennsylvania. ... Let us uproot and exterminate now this debasing, ultra-demoralizing, un-American and inhuman leprosy.[66]

- Roddenbery's proposal of the anti-miscegenation amendment unleashed a wave of racialist support for the move: 19 states that lacked such laws proposed their enactment. In 1913, Massachusetts, which had abolished its anti-miscegenation law in 1843, enacted a measure (not repealed until 2008)[67] that prevented couples who could not marry in their home state from marrying in Massachusetts.[68]

- In 1928, Senator Coleman Blease, a Democrat of South Carolina, proposed an amendment that went beyond the previous ones, requiring that Congress set a punishment for interracial couples attempting to get married and for people officiating an interracial marriage. This amendment was also never enacted.[69]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Woodson, Carter G. (1918), "The Beginnings of the Miscegenation of the Whites and Blacks", The Journal of Negro History, 3 (4): 335–353, doi:10.2307/2713814, JSTOR 2713814

- ^ a b c "Loving v. Virginia". Oyez. Archived from the original on 2019-05-11. Retrieved 2019-10-03.

- ^ a b c "Loving v. Virginia". LII / Legal Information Institute. Archived from the original on 2019-10-15. Retrieved 2019-10-03.

- ^ Fredrickson, George M. (1987), The Black Image in the White Mind, Wesleyan University Press, p. 172, ISBN 0-8195-6188-6

- ^ Karthikeyan, Hrishi; Chin, Gabriel Jackson (2011-04-14). "Preserving Racial Identity: Population Patterns and the Application of Anti-Miscegenation Statutes to Asian Americans, 1910-1950". SSRN 283998.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Martin, Byron Curti, Racism in the United States: A History of the Anti-Miscegenation Legislation and Litigation, pp. 1026, 1033–4, 1062–3, 1136–7 (See version Archived 2019-04-20 at the Wayback Machine of article in the USC Digital collection)

- ^ Courtroom History, Loving Day, archived from the original on 31 December 2007, retrieved 2008-01-02

- ^ Edward Stein (2004), Past and Present Proposed Amendments to the United States Constitution regarding marriage (PDF), vol. 82, Washing State University Law Quarterly, archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-12-01, retrieved 2008-01-04, archived from the original Archived March 7, 2008, at the Wayback Machine on 2006-08-12.

- ^ Viñas-Nelson, Jessica. "Interracial Marriage in "Post-Racial" America". The Ohio State University. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ Frank W Sweet (January 1, 2005), The Invention of the Color Line: 1691—Essays on the Color Line and the One-Drop Rule, Backentyme Essays, archived from the original on 2007-04-09, retrieved 2008-01-04

- ^ a b c Francis C. Assisi (2005), Indian-American Scholar Susan Koshy Probes Interracial Sex, INDOlink, archived from the original on 30 January 2009, retrieved 2 January 2009

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Echoes of Freedom: South Asian Pioneers in California, 1899-1965 - Chapter 9: Home Life, The Library, University of California, Berkeley, archived from the original on 18 February 2009, retrieved 2009-01-08

- ^ Interracial Marriage and Cohabitation Laws, Redbone Heritage Foundation, archived from the original on 2007-09-27, retrieved 2008-01-04

- ^ {fr} A. Mérignhac, Précis de législation & d'économie coloniales, librairie de la société du recueil Sirey, Paris 1912, p. 45

- ^ Kimberly S. Hanger, Bounded Lives, Bounded Places: Free Black Society in Colonial New Orleans,1769-1803. Durham N.C., and London: Duke University Press, 1997.

- ^ Battalora, Jacqueline (2013). The Birth of a White Nation: The Invention of White People and its Relevance Today. Houston Texas: Strategic Book Publishing and Rights Co.

- ^ Schafer, Daniel L. (2013). Zephaniah Kingsley and the Atlantic World: Slave Trader, Plantation Owner, Emancipator. University Press of Florida. ISBN 9780813044620.

- ^ Mixed Marriages In Louisiana Creole Families 164 marriages (August 18, 2018). "Landry Christophe" (PDF). Louisiana Historic & Cultural Vistas. pp. 8, 15. Retrieved April 23, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Kyle G. Volk, Moral Minorities and the Making of American Democracy Archived 2019-04-20 at the Wayback Machine (Oxford University Press, 2014), 104-116.

- ^ Steiner, Mark. "The Lawyer as Peacemaker: Law and Community in Abraham Lincoln's Slander Cases" Archived 2011-09-19 at the Wayback Machine "The Lawyer as Peacemaker: Law and Community in Abraham Lincoln's Slander Cases". September 19, 2011.. The History Cooperative

- ^ enacted similar anti-miscegenation laws."Chinese Laborers in the West" Archived 2011-07-26 at the Wayback Machine Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Program

- ^ Douglas, Stephen A. (1991). The Complete Lincoln-Douglas Debates of 1858. University of Chicago Press. p. 235.

- ^ Robinson II, Charles F., University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Archived 2011-09-05 at the Wayback Machine. The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture. (accessed January 4, 2007).

- ^ "Miscegenation and competing definitions of race in twentieth-century Louisiana".[permanent dead link]

- ^ Wallenstein, Peter, Tell the Court I love my wife

- ^ Francois, Aderson Bellegarde (October 2022). "Speak to Your Dead, Write for Your Dead: David Galloway, Malinda Brandon, and a Story of American Reconstruction". Georgetown Law Journal. 111 (1): 31–93.

- ^ Binning, F. Wayne (1981). "The Tennessee Republicans in Decline, 1869-1876: Part II". Tennessee Historical Quarterly. 40 (1): 68–84. ISSN 0040-3261. JSTOR 42626156.

- ^ "Florida Constitution of 1885". library.law.fsu.edu. Retrieved 2023-02-09.

- ^ a b Sohoni, Deenesh (2007). "Unsuitable Suitors: Anti-Miscegenation Laws, Naturalization Laws, and the Construction of Asian Identities". Law & Society Review. 41 (3): 587–618. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5893.2007.00315.x. ISSN 0023-9216. JSTOR 4623396.

- ^ a b Pascoe, Peggy (2009). What comes naturally: miscegenation law and the making of race in America. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509463-3.

- ^ "Legal Map – Loving Day". Retrieved 2023-02-09.

- ^ 59 Ariz. 16, 121 P.2d 882

- ^ Case Text

- ^ Garrow (2008). "Bad Behavior Makes Big Law: Southern Malfeasance and the Expansion of Federal Judicial Power, 1954-1968". St. John's Law Review. 82 (1).

- ^ Wright, Edward T. (1949). "Interracial Marriage: A Survey of Statutes and Their Interpretations" (PDF). Mercer Law Review. 01 (1): 83. Retrieved 28 Jan 2024.

- ^ John McGowan (15 December 1997). Hannah Arendt: An Introduction. University of Minnesota Press. p. 1. ISBN 9781452903385.

- ^ Gallup, Inc. (25 July 2013). "In U.S., 87% Approve of Black-White Marriage, vs. 4% in 1958". Gallup.com. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ^ Wallenstein, Peter (2004). Tell the Court I Love My Wife: Race, Marriage, and Law--An American History. St. Martin's Publishing Group. p. 185.

- ^ Tucker, Neely (June 13, 2006). "Loving Day Recalls a Time When the Union of a Man And a Woman Was Banned" Archived 2017-09-14 at the Wayback Machine. The Washington Post.

- ^ Van Hook v. Blanton, 206 So. 2d 210 (Fla. 1968).

- ^ Alabama removes ban on interracial marriage, USA Today, November 7, 2000, archived from the original on September 14, 2002, retrieved 2008-01-04

- ^ Suzy Hansen (2001-03-08). "Mixing it up". Salon. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ^ Matthew Green (March 24, 2013). "The Supreme Court Ended Mixed-Race Marriage Bans Less than 50 Years Ago". KQED News. Archived from the original on October 16, 2014. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- ^ "Mississippi Race and Marriage, Amendment 3 (1987)". Ballotpedia.

- ^ Bernard, Diane. "The United States' first interracial love song". www.bbc.com. Retrieved 2022-07-05.

- ^ Sullivan, Eileen (October 16, 2009). "Man's halt of interracial marriage sparks outrage". The New York Times. Associated Press.

- ^ "Humphrey v. Bardwell". Justia.

- ^ "La. justice quits after interracial flap - US news - Life - Race & ethnicity - NBC News". NBC News. November 3, 2009. Retrieved 2011-04-18.

- ^ "Vital Records Administration". The General Court of New Hampshire. Retrieved 2024-01-24.

- ^ "Couples were asked to tell their race for a Virginia marriage license. Now they're suing". NBC News. 7 September 2019. Archived from the original on 2019-09-16. Retrieved 2019-09-10.

- ^ "Virginia removes requirement to declare race on marriage forms". BBC News. 15 September 2019. Archived from the original on 2020-06-03. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- ^ "Law Student Helps Change Virginia Marriage License". 20 November 2019. Archived from the original on 2020-07-23. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- ^ "House Bill 1523". Archived from the original on 2020-01-26. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- ^ "Mississippi wedding venue refuses interracial pair over owner's Christian faith". BBC News. 3 September 2019. Archived from the original on 2019-12-02. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- ^ "Did Iowa ever have an anti-miscegenation law?". State Library of Iowa.

- ^ Min, Pyong-Gap (2006), Asian Americans: contemporary trneds and issues, Pine Forge Press, p. 189, ISBN 978-1-4129-0556-5

- ^ Pascoe, Peggy (2009). What comes naturally : miscegenation law and the making of race in America. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509463-3. OCLC 221155113.

- ^ Monahan, Thomas P. (Nov 1973). "Marriage across Racial Lines in Indiana". Journal of Marriage and Family. 35 (4): 633. doi:10.2307/350876. JSTOR 350876 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Bern Haggerty, Profile, WILLIAM JEFFERSON HARDIN: TWO STORIES ABOUT WYOMING'S FIRST BLACK LEGISLATOR, Wyoming Lawyer (February, 2000) (citing 1882 Wyo. Terr. Sess. Laws ch. 54)

- ^ Newbeck, Phyl (2008). Virginia Hasn't Always Been for Lovers: Interracial Marriage Bans and the Case of Richard and Mildred Loving. SIU Press. p. 194. ISBN 9780809328574. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- ^ "Interracial Marriage in "Post-Racial" America". Archived from the original on 2019-05-25. Retrieved 2019-05-25.

- ^ Brattain, Michelle (2005). "Miscegenation and Competing Definitions of Race in Twentieth-Century Louisiana". The Journal of Southern History. 71 (3): 621–658. doi:10.2307/27648822. ISSN 0022-4642. JSTOR 27648822.

- ^ See for example Stevens v. United States, 146 F.2d 120 (1944)

- ^ John R. Vile (2003), Encyclopedia of constitutional amendments, proposed amendments, and amending issues, 1789-2002 (second ed.), ABC-CLIO, p. 243, ISBN 978-1-85109-428-8

- ^ Rust and Rust, 1985, p. 147

- ^ Congressional Record, 62d. Congr., 3d. Sess., December 11, 1912, pp. 502–503.

- ^ "Governor signs law allowing out-of-state gays to wed". The Boston Globe. 2008-07-31. Archived from the original on 2012-10-21. Retrieved 2009-09-11.

- ^ "Big marriage rulings are coming in the next month". Gay People's Chronicle. 2006-02-17. Archived from the original on 2018-09-28. Retrieved 2009-09-11.

- ^ Anti-Miscagenation laws, Reference.com, archived from the original on 2012-11-20, retrieved 2017-10-09

Further reading (most recent first)

edit- Washington, Scott (2024). "Crossing the Line: A Quantitative History of Anti-Miscegenation Legislation in the United States, 1662–2000". American Journal of Sociology. 130 (3): 686–724.

- Spiro, Jonathan P. (2009), Defending the Master Race: Conservation, Eugenics, and the Legacy of Madison Grant, Univ. of Vermont Press, ISBN 978-1-58465-715-6

- Tucker, William H. (2007), The funding of scientific racism: Wickliffe Draper and the Pioneer Fund, University of Illinois Press, ISBN 978-0-252-07463-9

- Pascoe, Peggy. What Comes Naturally: Miscegenation Law and the Making of Race in America. Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Strandjord, Corinne. Filipino Resistance to Anti-Miscegenation Laws in Washington State Great Depression in Washington State Project, 2009.

- Johnson, Stefanie. Blocking Racial Intermarriage Laws in 1935 and 1937: Seattle's First Civil Rights Coalition Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project, 2005.

- Weierman, Karen Woods (2000). "For the Better Government of Servants and Slaves: The Law of Slavery and Miscegenation". Legal Studies Forum. 24 (1): 133–156 – via HeinOnline.

- Gilmore, Al-Tony (January 1973). "Jack Johnson and White Women: The National Impact". Journal of Negro History. 58 (1): 18–38. doi:10.2307/2717154. JSTOR 2717154. S2CID 149937203.

External links

edit- Loving v. Virginia (No. 395) Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute

- Loving at Thirty by Harvard Law School Professor Randall Kennedy at SpeakOut.com

- Loving Day: Celebrate the Legalization of Interracial Couples

- "The Socio-Political Context of the Integration of Sport in America", R. Reese, Cal Poly Pomona, Journal of African American Men (Volume 4, Number 3, Spring, 1999)