This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. (September 2021) |

Milicia excelsa is a tree species from the genus Milicia of the family Moraceae. Distributed across tropical Central Africa, it is one of two species (the other being Milicia regia) yielding timber commonly known as ọjị, African teak, iroko, intule, kambala, moreira, mvule, odum and tule.

| Milicia excelsa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Moraceae |

| Genus: | Milicia |

| Species: | M. excelsa

|

| Binomial name | |

| Milicia excelsa (Welw.) C.C. Berg

| |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

Description

editThe species is a large deciduous tree growing up to 50 metres (160 feet) high. The trunk is bare lower down with the first branch usually at least 20 m (66 ft) above the ground. It often has several short buttress roots at the base. The bark is pale or dark gray, thick but little fissured, and if it gets damaged it oozes milky latex. There are a few thick branches in the crown all fairly horizontal giving an umbrella shape. The smaller branches hang down in female trees and curve up in male trees. The leaves are 5 to 10 centimetres (2 to 4 inches) long, ovate or elliptical with a finely toothed edge, green and smooth above and slightly downy beneath. Older leaves turn yellow, and all of the leaves have a prominent rectangular mesh of veins visible on the underside. The trees are dioecious. Male trees have white catkins that extend 15 to 20 cm (6 to 8 in) and dangle from twigs at the axils of the leaves. Female trees have flower spikes measuring 5 to 6 cm (2 to 2+1⁄4 in) long by 2 cm (3⁄4 in) wide, green with prominent styles. The fruit are long, wrinkled and fleshy with the small seeds embedded in the pulp.[2]

There is evidence that some of the variation that is described above amongst individuals is due to the variation in the environment. In a study done in 2010, it was found that environmental change from different regions in Benin caused much of the variation in M. excelsa. Many studies have attributed this variation in growth to the differences in climate of regions. Specifically, soil characteristics and rainfall played a major role in the morphological variation of trunk growth of M. excelsa.

Phylogeny

editIn a study[3] it was seen that isolation was caused by one or more of the animals that are known for dispersal of M. excelsa (i.e. bats, rodents, and birds). It is hypothesized that the ancestor slowly developed a different flowering time from its ancestor, which led to differences in selection pressure during the time of reproduction. This, over time, has resulted in the tree that we see today commonly known as Iroko. Although this is the theory that has the most evidence, it is possible for M. excelsa to have evolved in a different way.

Distribution and habitat

editAfrican teak is distributed across tropical West, East, and Central Africa. Its range extends from Guinea-Bissau in the west to Mozambique in the east. It is found in Angola, Benin, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, the Republic of the Congo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Nigeria, Rwanda, São Tomé and Príncipe, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Its natural habitat is in wet savannah, rainforest, riverine and low-altitude evergreen forests. It can tolerate an annual rainfall of less than 70 cm (28 in) or six months of drought as long as there is a stream or a ground water source nearby.[2]

In a study done on population distribution of M. excelsa in 2009,[4] researchers found that most of the populations that were being studied were inbred. After some analysis the researchers found that the M. excelsa was inbreeding due to lack of proximity to other M. excelsa individuals. Inbreeding could contribute to why this species is moving closer to being on the Threatened conservation list. If the numbers of mates available are not high enough because dispersion methods are not effective over long distances, then the species will begin to suffer from inbreeding depression (inbreeding can lead to accumulation of recessive deleterious alleles in a population).

Ecology

editFlowering takes place at a range of different times, but often occurs in January and February soon after the time when most of the leaves fall or shortly before the new leaves appear. The fruits take about a month to ripen and are eaten by squirrels, bats, and birds, which then disperse the seeds in their droppings.[2] Some populations, especially plantations, are attacked by a gall mite.

A study in Ghana found that this tree relies heavily on the straw-coloured fruit bat (Eidolon helvum) for seed dispersal, over 98% of the seed falling to the ground having passed through its gut.[5] This seed also germinated better than uneaten seed and resisted predation longer.[5]

Importance to the environment

editIn a study done on the mineralization of M. excelsa,[6] it was observed that in certain conditions Milicia acts as a carbon sink. These specific conditions are characterized by presence of oxalate, bacteria for oxalate oxidation and a dry season, which are common conditions in which Milicia tends to grow. This is important because the conversion of atmospheric carbon into land carbon decreases the amount of atmospheric carbon dioxide.

Because of its importance to the environment there has been research done on how to conserve Iroko. A solution that has been proposed to help M. excelsa move further away from being threatened is agroforestry. It was found that agroforestry helps increase habitat for plants and animals. More importantly, agroforestry promotes the growth of any plant species by taking pressure off remnant forests that usually have to repopulate threatened species on their own.[7] The people that conducted this study found that it would be a good method to use to specifically fight against the slow decline of the Iroko species.[7] However, most of the people that were surveyed for the study did not use this system specifically to regenerate this species, therefore even though there is hope in helping this species the measures have not been taken to do so.

When forests are felled, isolated trees are often left standing and the tree regenerates easily. Fresh seed germinates readily but it loses viability in storage.[1]

Conservation

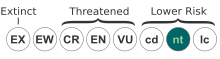

editBecause of these and many other uses of M. excelsa, people have over-harvested this species to the point of concern. The International Union for Conservation of Nature has this species on the Red List under 'Near Threatened'.[4] A study has reported that most of the remaining Iroko trees in Benin were conserved on farms.[7] M. excelsa is threatened by habitat loss.[1]

Uses

editMilicia excelsa is one of two tree species (the other being Milicia regia) that yield timber commonly known as African teak.

M. excelsa yields a strong, dense and durable dark brown hardwood timber. It is resistant to termites and is used for construction, furniture, joinery, panelling, floors and boats.[8] Iroko has been used in recent refit work performed on the Royal Navy's 104-gun first-rate ship of the line HMS Victory.

The tree can be used in the control of erosion, and for providing shade as a roadside tree in urban areas. It grows rapidly, can be coppiced and is ready for cutting after about fifty years. The tree leaves are used for mulching.[9]

The tree is also used in herbal medicine. The powdered bark is used for coughs, heart problems and lassitude. The latex is used as an anti-tumour agent and to clear stomach and throat obstructions. The leaves and the ashes also have medicinal uses.[9]

In culture

editIn West Africa, African teak is considered to be a sacred tree. It is often protected when the surrounding bush is cleared, ritual sacrifices take place underneath it and gifts are given to it. Fertility and birth are associated with it and its timber is used to make ceremonial drums and coffins.[10]

References

edit- ^ a b c World Conservation Monitoring Centre (1998). "Milicia excelsa". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1998: e.T33903A9817388. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1998.RLTS.T33903A9817388.en. Retrieved 14 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Wood Species Database: Iroko - TRADA". Retrieved 2018-08-24.

- ^ 1. Dainou, K., E. Laurenty, G. Mahy, O. J. Hardy, Y. Brostaux, N. Tagg, and J.-L. Doucet. "Phenological Patterns in a Natural Population of a Tropical Timber Tree Species, Milicia Excelsa (Moraceae): Evidence of Isolation by Time and Its Interaction with Feeding Strategies of Dispersers." American Journal of Botany (2012): 1453-463. Print.

- ^ a b J.-P. Bizoux, K. Dai’nou, N. Bourland, O. J. Hardy, M. Heuertz, G. Mahy, and J.-L. Doucet, 2009, Spatial genetic structure in Milicia excelsa (Moraceae) indicates extensive gene dispersal in a low-density wind-pollinated tropical tree, Molecular Ecology, 6-10

- ^ a b Taylor, Daniel; Kankam, Bright; Wagner, Michael The role of the fruit bat, Eidolon helvum, in seed dispersal, survival, and germination in Milicia excelsa, a threatened West African hardwood. Northern Arizona University School of Forestry.

- ^ Braissant, Olivier, Guillaume Cailleau, Michel Aragno, and Eric P. Verrecchia. "Biologically Induced Mineralization in the Tree Milicia Excelsa (Moraceae): Its Causes and Consequences to the Environment." Geobiology: 59-66. Print.

- ^ a b c Christine Ouinsavi and Nestor Sokpon, 2008, Traditional agroforestry systems as tools for conservation of genetic resources of Milicia excelsa Welw. C.C. Berg in Benin, Agroforestry Systems, 17-26

- ^ "Iroko - The Wood Database". Retrieved 2018-08-24.

- ^ a b "Milicia excelsa". Indigenous multipurpose trees of Tanzania: uses and economic benefits. Food and Agriculture Organisation: Forestry Department. Retrieved 2012-07-29.

- ^ "3.3 The symbolic and sacred significance of particular forest resources". The cultural and symbolic importance of forest resources. Food and Agriculture Organisation: Forestry Department. Retrieved 2012-07-29.

External links

edit- Data related to Milcia excelsa at Wikispecies