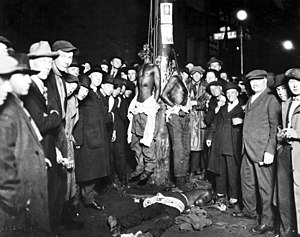

On June 15, 1920, three African-American circus workers, Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson, and Isaac McGhie, suspects in an assault case, were taken from the jail and lynched by a White mob of thousands in Duluth, Minnesota. Rumors had circulated that six Black men had raped and robbed a nineteen-year-old White woman. A physician who examined her found no physical evidence of rape.

| Duluth lynchings | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Nadir of American race relations | |

| |

| Location | Duluth, Minnesota |

| Target | Six arrested suspects |

| Victims | Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson, and Isaac McGhie |

| Perpetrators | Mob (estimated 1,000 - 10,000 participants) |

| Motive | The alleged rape of Irene Tusken |

The 1920 lynchings are the only known instance of lynching of African-Americans in Minnesota. Twenty other lynchings were recorded in Minnesota, and included mainly Native Americans and Whites.[1] Three men were convicted of rioting, but none served more than fifteen months. No one was ever prosecuted for the murders.

The state of Minnesota passed anti-lynching legislation in April 1921, and lynchings have not been recorded in Minnesota since.[1] In 2003, the city of Duluth erected a memorial to the lynched men.[2] In 2020, Max Mason, who was a co-worker in the same traveling circus as the three men who were lynched, was convicted in court after the lynchings, was granted the first posthumous pardon in the history of the state.[3]

Background

editThe industrial city of Duluth had been growing rapidly in the early 20th century, attracting many European immigrants. By 1920 one third of its population of 100,000 was foreign-born, with immigrants from Scandinavia, Germany, Poland, Italy, Austria-Hungary, and the Russian Empire. Many of the immigrants lived in West Duluth, a working-class section of the city. The African-American community in the city was small, with a total population of 495, but a number had been hired by US Steel, the major employer in the area.[4]

In September 1918, a Finnish immigrant named Olli Kinkkonen was lynched in Duluth, allegedly for dodging military service in World War I, which the United States had recently entered.[5] Kinkkonen was found dead, tarred and feathered, and hanging from a tree in Lester Park. Authorities did not pursue murder charges; they claimed that he had committed suicide after the shame of having been tarred and feathered.[5]

During and immediately following World War I, a large population of blacks began the Great Migration out of the agrarian South to the industrial North to escape racial violence and to gain more opportunities for work, education, and voting. African-Americans competed with working-class immigrants and ethnic whites for the lower-grade jobs. Many felt the black migrants threatened their jobs and pay.[6]

The period after World War I was disruptive in the United States, as numerous veterans sought to re-enter the job market and society. The government had no program to help them. Racial antagonism erupted in 1919 as race riots of whites against blacks in numerous cities across the U.S.; it was called the Red Summer of 1919. Unlike in mob action in the South, blacks in Chicago and other cities fought back against these attacks.[citation needed]

Event

editOn June 14, 1920, the John Robinson Circus arrived in Duluth for a free parade and a one-night performance. Two local white teenagers, Irene Tusken, age 19, and James "Jimmie" Sullivan, 18, met at the circus and ended up behind the big top, watching the black workers dismantle the menagerie tent, load wagons and generally get the circus ready to move on. It is unknown what took place between Tusken, Sullivan and the workers. Later that night Sullivan claimed to his father that he and Tusken were assaulted, and that Tusken was raped and robbed by five or six black circus workers, who were part of the crew.[citation needed]

In the early morning of June 15, Duluth police chief John Murphy received a call from James Sullivan's father, saying six black circus workers had held his son and girlfriend at gunpoint and then raped and robbed Irene Tusken. Chief Murphy lined up all 150 or so roustabouts, food service workers, and props-men on the side of the tracks, and asked Sullivan and Tusken to identify their attackers. The police arrested six black men as suspects in connection with the rape and robbery and held them in custody in the city jail.[4]

Sullivan's claim that Tusken was raped has been questioned. When she was examined by a physician, Dr. David Graham, on the morning of June 15, he found no physical evidence of rape or assault.[4][additional citation(s) needed]

Newspapers printed articles about the alleged rape; rumors spread in the white community about it, including that Tusken was dying from her injuries. That evening, a mob of between 1,000 and 10,000 men[4] formed outside the Duluth city jail. A Catholic priest reportedly tried to deter them, but to no avail.[7]

The Duluth commissioner of public safety, William F. Murnian, ordered the police not to use their guns to protect the prisoners. The mob used heavy timbers, bricks, and rails to break down doors and windows,[4] pulling the six black men from their cells. The mob seized Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson, and Isaac McGhie. They took them out and convicted them of Tusken's rape in a kangaroo court. The mob took the three men one block to the intersection 1st Street and 2nd Avenue East, where they beat them and hanged them from a light pole.[4]

The next day, the Minnesota National Guard arrived at Duluth to secure the area and to guard the surviving prisoners, as well as ten additional black suspects whom the police had arrested from the circus at its next stop. They were moved under heavy guard to the jail of St. Louis County.[4]

Aftermath

editReactions

editThe killings made headlines throughout the country. The Chicago Evening Post wrote: "This is a crime of a Northern state, as black and ugly as any that has brought the South in disrepute. The Duluth authorities stand condemned in the eyes of the nation." An article in the Minneapolis Journal accused the lynch mob of putting a "stain on the name of Minnesota", stating: "The sudden flaming up of racial passion, which is the reproach of the South, may also occur, as we now learn in the bitterness of humiliation, in Minnesota."[4]

The June 15 Ely Miner reported that just across the bay in Superior, Wisconsin, the acting chief of police declared: "We are going to run all idle negroes out of Superior and they're going to stay out." How many were forced out is not certain. All of the blacks employed by a carnival in Superior were fired and told to leave the city.[4]

Prominent blacks in Duluth complained that the city had not protected the circus workers. The mayor, commissioner of public safety and police chief were criticized for their failures to break up the mob before it had gotten so powerful. A special grand jury was called to investigate the lynchings. It said that Murnian was "not competent" and the police department was in need of a "thorough overhauling".[4]

Trials

editTwo days later, on June 17, Judge William Cant and the grand jury had a difficult time identifying the lead mob members. In the end the grand jury issued thirty-seven indictments for the lynching mob. Twenty-five were for rioting and twelve for the crime of murder in the first degree. Some men were indicted on both charges. Three men: Louis Dondino, Carl Hammerberg, and Gilbert Stephenson were convicted of rioting; none served more than 15 months in prison. No one was convicted for the murders of the three black men.[4]

Prosecution continued against the other black circus workers. Despite the lack of significant physical evidence, seven men were indicted for rape. The NAACP had protested to the city about the lynchings. It hired defense attorneys for the men, and charges were dismissed for five. Max Mason and William Miller were tried for rape. Miller was acquitted, but Mason was convicted and sentenced to serve seven to thirty years in prison. He was a native of Decatur, Georgia, who had been traveling with the circus as a worker. He appealed his case without success. He was incarcerated at Stillwater State Prison, serving four years, from 1921 to 1925. He was released on the condition that he would leave the state.[4]

Anti-lynching law

editWilliam T. Francis, associate counsel for Max Mason, was an attorney from St. Paul. He and his wife Nellie Francis continued to work after the trial on anti-lynching legislation, which the state of Minnesota passed in April 1921.[4] The law provided for compensation of "relatives of victims and suspended police officials who failed to protect prisoners from mobs."[1] No lynchings have since taken place in the state.[1] The anti-lynching law was repealed in Minnesota in 1984.[8] However, the 1968 Civil Rights Act ensured that hate crimes based on race could be prosecuted at the federal level.[9] Minnesota also has a hate crime law which ensures cooperation with the federal government to prosecute those who committed hate crimes defined in the 1968 Civil Rights Act as well.[9]

Legacy

editIrene Tusken's great nephew, as of 2020, is the chief of the Duluth Police Department.[10]

Memorial

editResidents of Duluth began to work on ways to commemorate the victims of the lynching. The Clayton Jackson McGhie Scholarship Committee set up a fund in 2000, and awarded its first scholarship in 2005.[11]

On October 10, 2003, a plaza and statues were dedicated in Duluth to the three men who were killed. The bronze statues are part of a memorial across the street from the site of the lynchings. The Clayton Jackson McGhie Memorial was designed and sculpted by Carla J. Stetson, in collaboration with editor and writer Anthony Peyton-Porter.[12][13]

At the memorial's opening, thousands of citizens of Duluth and surrounding communities gathered for a ceremony. The final speaker at the ceremony was Warren Read, the great-grandson of one of the most prominent leaders of the lynch mob:

It was a long-held family secret, and its deeply buried shame was brought to the surface and unraveled. We will never know the destinies and legacies these men would have chosen for themselves if they had been allowed to make that choice. But I know this: their existence, however brief and cruelly interrupted, is forever woven into the fabric of my own life. My son will continue to be raised in an environment of tolerance, understanding and humility, now with even more pertinence than before.

Read has written a memoir exploring his learning about his great-grandfather's role in the lynching, as well his decision to find and connect with the descendants of Elmer Jackson, one of the men killed that night. Read's book, The Lyncher in Me, was published in March 2008.[14]

100th anniversary commemoration

editOn June 15, 2020, the 100th anniversary of the lynchings, Minnesota Governor Tim Walz visited the memorial and issued a proclamation recognizing the day as Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson, and Isaac McGhie Commemoration Day.[15][16] In his proclamation, Walz stated "The foundational principles of our State and Nation were horrifically and inexcusably violated on June 15, 1920, when Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson, and Isaac McGhie, three Black men, were wrongfully accused of a crime", and "We must not allow such communal atrocities to happen again. Everyone must be aware of this tragic history." He compared the lynchings to the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis three weeks before.[17]

Cultural reference

editThe first verse of the 1965 song "Desolation Row" by Bob Dylan references the lynchings in Duluth:

They're selling postcards of the hanging

They're painting the passports brown

The beauty parlor is filled with sailors

The circus is in town.[18]

Dylan was born in Duluth, and grew up in Hibbing, 60 miles (97 km) northwest of Duluth. His father, Abram Zimmerman, was 9 years old in June 1920 and lived two blocks from the site of the lynchings.[19]

Posthumous pardon

editIn 2020, during the George Floyd protests Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison proposed that the related 1920 conviction of Max Mason, a black man convicted of raping an 18-year-old woman, was a false charge and should be reversed.[20] On June 12, 2020, the Minnesota Board of Pardons granted Max Mason the first posthumous pardon in the history of the state of Minnesota.[3] In 1920, Mason, who was working in the same traveling circus as the three who were lynched, was convicted of rape and sentenced to 30 years in prison.[contradictory][3] He was released from prison after four years on the condition that he not return to Minnesota for 16 years.[3]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d Ziebarth, Marilyn (Summer 1996). "Judge Lynch in Minnesota" (PDF). Minnesota History. 55 (2): 72. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 10, 2022. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ Kraker, Dan (June 15, 2013). "Duluth marks anniversary of memorial to 3 lynching victims". www.mprnews.org. Archived from the original on March 1, 2016. Retrieved February 19, 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Minnesota grants state's first posthumous pardon to black man in 1920 case that led to lynchings". CBS News. June 12, 2020. Archived from the original on June 15, 2022. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Duluth Lynchings: On line Resource". Minnesota Historical Society. Archived from the original on February 21, 2006. Retrieved March 9, 2006.

- ^ a b "MPR: Postcard From A Lynching". news.minnesota.publicradio.org. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- ^ "Duluth Lynchings: Presence of the Past" Archived June 29, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Twin Cities Public Television.

- ^ Ellis, Elizabeth (September 20, 2009). "Famous footprints: Roy Wilkins, Whitney Young other Black greats' steps in MN". Twin Cities Daily Planet. Archived from the original on December 8, 2021. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- ^ "Minn. Laws 1984, chapt. 629, sec. 4". Archived from the original on September 26, 2021. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- ^ a b "Laws and Policies". May 25, 2021. Archived from the original on December 20, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ "Duluth's new police chief acknowledges great-aunt's role in 1920 lynching". June 18, 2016. Archived from the original on November 21, 2021. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ^ "Clayton Jackson McGhie Memorial Scholarship Fund". Duluth Superior Area Community Foundation. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- ^ Kelleher, Bob (June 8, 2003). "Lynching victims memorial takes shape in Duluth". Minnesota Public Radio. Archived from the original on March 31, 2022. Retrieved November 3, 2012.

- ^ "Creation of the Memorial". claytonjacksonmcghie.org. November 8, 2003. Archived from the original on August 25, 2010. Retrieved November 3, 2012.

- ^ The Lyncher in Me; A Search for Redemption in the Face of History. Archived May 4, 2022, at the Wayback Machine Read, Warren.

- ^ "Walz visits Clayton-Jackson-McGhie Memorial in Duluth, urges action to create change | KSTP.com". kstp.com. Archived from the original on June 15, 2020.

- ^ "Governor Tim Walz Officially Recognizes Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson, and Isaac McGhie Commemoration Day". Archived from the original on September 26, 2021. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- ^ Galioto, Katie, "'An unbroken line': Gov. Tim Walz connects Duluth lynchings 100 years ago to George Floyd's death'" Archived June 15, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, Minneapolis Star Tribune, June 15, 2020.

- ^ Dylan, Bob. "Desolation Row". bobdylan.com. Archived from the original on December 15, 2012. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- ^ Hoekstra, Dave (July 1, 2001). "Dylan's Duluth Faces Up to Its Past". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on June 29, 2014. Retrieved May 29, 2014. See also: Polizzotti, Mark, Highway 61 Revisited, Continuum, 2006, ISBN 0-8264-1775-2, pp. 139-141

- ^ "Century after Minnesota lynchings, black man convicted of rape 'because of his race' up for pardon". Washington Post. June 12, 2020. Archived from the original on January 21, 2022. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

Further reading

edit- Fedo, Michael (2000). The Lynchings in Duluth. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press. ISBN 0-87351-386-X.

External links

edit- Clayton Jackson McGhie Memorial

- Clayton Jackson McGhie Memorial Scholarship Fund, Duluth Superior Area Community Foundation/

- Memorial Facebook page

- Olsen, Ken. "Duluth Remembers 1920 Lynching". Tolerance.org. Archived from the original on March 1, 2006. Retrieved March 9, 2006.

46°47′21″N 92°05′48″W / 46.7893°N 92.0968°W

- "Duluth Lynchings Online Resources". Minnesota Historical Society. 2003. Archived from the original on February 7, 2006. Retrieved February 15, 2019.