İslâm III Giray (Crimean Tatar: اسلام كرای ثالث, romanized: İslâm Gäray-i S̱âlis̱; 1604 – 10 July 1654) was khan of the Crimean Khanate for ten years (1644–1654), interrupting the reign of his brother Mehmed IV Giray. He was khan during the Khmelnytsky uprising of the Cossacks against Poland.

| İslâm III | |

|---|---|

| |

| Khan of the Crimean Khanate | |

| Reign | 1644–1654 |

| Predecessor | Mehmed |

| Successor | Mehmed IV |

| Born | 1604 |

| Died | 10 July 1654 (aged 53–54) |

| Dynasty | Giray |

| Religion | Islam |

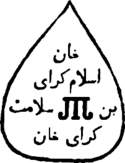

| Signature |  |

Ancestors and early life

editHe was one of the many sons of khan Selyamet I (1608–10), three of whom were khans and four of whom were fathers of khans. See Selâmet I Giray#His sons. He was preceded and followed by his younger brother Mehmed IV. None of his sons were khans. Subsequent khans were mostly descended from his brother Bahadir.

During the second reign of Canibek Giray (1628–1635) he was a captive in Poland circa 1629–1632 [1] Under Bahadır I Giray (1637–41) he served as kalga. In 1637 or 1638 he led the Budjak Horde back to Crimea. In the winter of 1639–40 he captured 8000 Ukrainian slaves for the Turkish galleys. In 1641 Bahadir was followed by his and İslâm's brother Mehmed IV even though İslâm was older. İslâm went to Turkey and settled at a place called Sultania on the western side of the Dardanelles.

Reign

editIn 1644 the Ottoman Sultan dismissed İslâm's brother Mehmed IV and placed İslâm on the throne. İslâm appointed his younger brother Kyrym as kalga. As nureddin he continued Gazi, the son of his brother Mubarak. In 1651 Kyrym was killed at the Battle of Berestechko and was replaced by Gazi, the new nureddin being İslâm's younger brother Adil. Kyrym, Mubarak and Adil were all fathers of khans. İslâm is remembered as a builder and successful administrator. He tended to appoint non-nobles without antagonizing the clan leaders. For the Ukrainian rebellion see below. In 1654 he died of natural causes.

Khmelnytsky Uprising

editThe Khmelnytsky Uprising of the Zaporozhian Cossacks against Poland started in January 1648 when Khmelnytsky became hetman of the Cossacks. In March Khmelnytski went to Crimea and made an anti-Polish alliance.[2] This gave him extra cavalry, mainly under Togay Bey. The Poles tried, with occasional success, to split the alliance. Crimean horsemen accompanied Khmelnytsky on this 1648 campaign when he got almost as far as Lviv. Next year İslâm helped win the Battle of Zboriv (1649). The withdrawing Tatars were permitted to ravage the country they passed through. Some claim that İslâm was bribed by the Poles and that he ravaged mostly Cossack territory.[3] In 1651 the Poles sent a large army and won the Battle of Beresteczko because the Tatars fled the field. Khmelnytsky went after them and was held hostage for a while by İslâm. In 1652, following the Battle of Batih, the Cossacks purchased the Polish prisoners from the Tatars and slaughtered them. Howorth says that in 1653 İslâm ravaged the country around Bar and Kaminetz and left after receiving a ransom.[4] Other sources have İslâm present at the Battle of Zhvanets at about the same time. In January 1654, by the Treaty of Pereyaslav, the Cossacks accepted Russian supremacy, thereby provoking the Russo-Polish War (1654–1667). İslâm died shortly after.

Source and footnotes

edit- Henry Hoyle Howorth, History of the Mongols, 1880 (sic), Part 2, pp 547–552. Very old and possibly inaccurate in places.

- ^ Gaivoronsky, says he was captured by the Poles circa 1629 (p 168) and released circa 1632 (p 179), but spent 'five years' in Polish captivity (p. 233). The Russian Wikipedia has him in Polish captivity from 1629 to 1636 and then go to Turkey.

- ^ A Cossack-Tatar alliance seems unnatural, but it had happened before. In 1624 captured Cossacks successfully defended a khan against the Turks. In 1625 there was a brief alliance. In 1628–29 Cossacks supported a khan against overthrow. Three time they invaded, or tried to invade, Crimea. In 1636 Cossacks supported a khan who was resisting he Turks. In 1637 some Cossack rebels tried to gain Crimean support.

- ^ Brian L. Davies, Warfare, State and Society on the Black Sea Steppe, 2007, page 105

- ^ Howorth (1880), p551, following von Hammer (1856), needs a more modern source.