Julius Caesar Watts Jr. (born November 18, 1957) is an American politician, clergyman, and former football player. Watts played as a quarterback in college football for the Oklahoma Sooners and later played professionally in the Canadian Football League (CFL). He served in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1995 to 2003 as a Republican, representing Oklahoma's 4th congressional district.

J. C. Watts | |

|---|---|

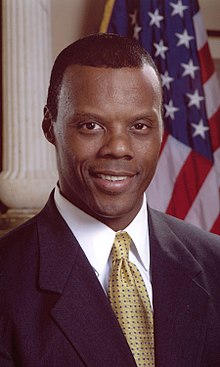

Watts in September 2003 | |

| Chair of the House Republican Conference | |

| In office January 3, 1999 – January 3, 2003 | |

| Leader | Dennis Hastert |

| Vice Chair | Tillie Fowler Deborah Pryce |

| Preceded by | John Boehner |

| Succeeded by | Deborah Pryce |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Oklahoma's 4th district | |

| In office January 3, 1995 – January 3, 2003 | |

| Preceded by | Dave McCurdy |

| Succeeded by | Tom Cole |

| Oklahoma Corporation Commissioner | |

| In office 1991–1995 | |

| Preceded by | James B. Townsend |

| Succeeded by | Ed Apple |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Julius Caesar Watts Jr. November 18, 1957 Eufaula, Oklahoma, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse |

Frankie Jones (m. 1977) |

| Children | 6, including Trey |

| Relatives | Wade Watts (uncle) |

| Education | University of Oklahoma (BA) |

| Football career | |

A football from the Oklahoma Sooners and signed by the team. Notable signatures include Billy Sims (1978 Heisman Trophy winner) and J. C. Watts. On the white quarter of the football an inscription to Ford was written in red. | |

| Career information | |

| Position(s) | Quarterback |

| College | Oklahoma |

| Career history | |

| As player | |

| 1981–1986 | Ottawa Rough Riders |

| 1986 | Toronto Argonauts |

| Honors |

|

Watts was born and raised in Eufaula, Oklahoma, in a rural impoverished neighborhood. After being one of the first children to attend an integrated elementary school, he became a high school quarterback and gained a football scholarship to the University of Oklahoma. He graduated from college in 1981 with a degree in journalism and became a football player in the Canadian Football League until his retirement in 1986.

Watts became a Baptist minister and was elected in 1990 to the Oklahoma Corporation Commission as the first African-American in Oklahoma to win statewide office. He successfully ran for Congress in 1994 and was re-elected to three additional terms with increasing vote margins. Watts delivered the Republican response to Bill Clinton's 1997 State of the Union address and was elected Chair of the House Republican Conference in 1998. He retired in 2003 and turned to lobbying and business work, also occasionally serving as a political commentator.

Early life and career

editWatts was born in Eufaula in McIntosh County, Oklahoma[1] to J. C. "Buddy" Watts Sr., and Helen Watts (d. 1992).[2] His father was a Baptist minister, cattle trader,[3] the first black police officer in Eufaula,[4] and a member of the Eufaula City Council.[5] His mother was a homemaker.[6] Watts is the fifth of six children and grew up in a poor rural African-American neighborhood.[7] He was one of two black children who integrated the Jefferson Davis Elementary School in Eufaula and the first black quarterback at Eufaula High School.[4]

While in high school, Watts fathered a daughter with a white woman, causing a scandal.[8] Their families decided against an interracial marriage because of contemporary racial attitudes and Watts' family provided for the child until she could be adopted by Watts' uncle, Wade Watts, a Baptist minister, civil rights leader and head of the Oklahoma division of the NAACP.[8]

He graduated from high school in 1976 and attended the University of Oklahoma on a football scholarship.[1][9] In 1977, Watts married Frankie Jones, an African-American woman with whom he had fathered a second daughter during high school.[6][8]

Watts began his college football career as the second-string quarterback and left college twice, but his father convinced him to return, and Watts became starting quarterback of the Sooners in 1979 and led them to consecutive Orange Bowl victories.[5] Watts graduated from college in 1981 with a Bachelor of Arts[1] in journalism.[5] Watts was selected by the New York Jets of the National Football League in the eighth round of the 1981 NFL Draft. The Jets tried Watts at several positions and could not guarantee that he would play quarterback, so he opted to sign with the CFL's Ottawa Rough Riders. As Ottawa's quarterback, he helped the team reach the 1981 Grey Cup game, which they nearly won in an upset.[5] Watts stayed with the Rough Riders from 1981 to 1985 and played a season for the Toronto Argonauts before retiring in 1986.[5][10]

Watts returned to Oklahoma and became a youth minister in Del City and was ordained as a Baptist minister in 1993.[6] He is a teetotaler.[11] Watts opened a highway construction company and later cited discontent with government regulation of his business as reason to become a candidate for public office.[6] Watts' family was affiliated with the Democratic Party and his father and uncle Wade Watts were active in the party, but it did not help Watts when he ran for public office and he changed his party affiliation in 1989, months before his first statewide race.[5][9] Watts later stated he had first considered changing parties when, as a journalism student, he covered the 1980 U.S. Senate campaign of Republican Don Nickles.[6] Watts' father and uncle continued to strongly oppose the Republican party, but supported him.[2][12] Watts won election to the Oklahoma Corporation Commission in November 1990[7] for a six-year term[2] as the first African-American elected to statewide office in Oklahoma.[13] He served as a member of the commission from 1990 to 1995 and as its chairman from 1993 to 1995.[1]

U.S. House of Representatives

edit1994 congressional election

editWatts ran for Congress in 1994 to succeed Dave McCurdy, who had announced his retirement from the House of Representatives to run for the Senate. He positioned himself as both a fiscal and social conservative, favoring the death penalty, school prayer, a balanced budget amendment and welfare reform, and opposing abortion, gay rights, and reduced defense spending.[6] After a hard-fought primary campaign[3] against state representative Ed Apple, Watts won 49 percent to Apple's 48 percent of the vote in August 1994, and 52 percent in the resulting run-off election in September 1994 with the support of Representative Jack Kemp and actor and National Rifle Association president Charlton Heston.[6] Watts started his race against the Democratic nominee, David Perryman, a white lawyer from Chickasha, with a wide lead in several early polls and 92 percent name recognition in one poll.[13] Watts hosted former President George H. W. Bush, U.S. Senator Bob Dole, and Minority Whip Newt Gingrich[6] and focused on welfare reform and the necessity of capital formation and capital gains, as well as a reduction in the capital gains tax as beneficial for urban blacks.[13] Some voters were expected to not vote for Watts because of race, but the editor of a local political newspaper argued Watts' established Christian conservative image and his popularity as a football player would help him win.[13] On November 8, 1994, Watts was elected with 52 percent of the vote[14] as the first African-American Republican U.S. Representative from south of the Mason–Dixon line since Reconstruction.[15] He and Gary Franks of Connecticut were the only two African-American Republicans in the House.[15] Oklahoma's Fourth District at the time was 90 percent white and had been represented by Democrats since 1922.[5]

As Congressman, Watts was assigned to the Armed Services Committee and the Financial Services Committee.[6] Watts emphasized moral absolutes and was considered in line with Republican Speaker Newt Gingrich's agenda,[15] the Contract with America,[6] and at the time was the only African-American who did not join the Congressional Black Caucus.[11] He initially supported ending affirmative action, declaring inadequate education the main obstacle for racial equality, but subsequently opposed legislation banning the practice for the federal government.[6] Watts focused on promoting his party, attending NAACP meetings and meeting with representatives from historically black colleges.[6] In 1995, Watts was named national co-chairman for the presidential campaign of Republican Bob Dole.[9]

Reelection and successive terms

editWatts' 1996 reelection campaign featured state representative Ed Crocker as the Democratic candidate[16] in a negative campaign.[2] Crocker questioned Watts' business dealings because of tax issues for a real estate company of which Watts was the principal owner, and whether he was paying child support for one of his daughters born out of wedlock.[16] Crocker suggested Watts might use drugs or sanction their use because he declined to participate in a voluntary drug screening in the House of Representatives.[17] Watts denied the charge, took the test, and accused Crocker of draft dodging during the Vietnam War and later living at the "center of the West Coast drug culture."[17] Watts was given a featured speaking role at the 1996 Republican National Convention[17] and was re-elected with 58 percent of the vote in the 1996 U.S. House election.[14]

Following the election, Watts switched from the Financial Services Committee to the House Transportation Committee.[6] He was the only African-American Republican in the House and was chosen to deliver the Republican reply to President Bill Clinton's State of the Union address in February 1997,[4] the youngest congressman and first African-American to do so.[5] In his response, Watts focused on providing a positive vision of the Republican Party and advocated deficit and tax reduction and faith-based values.[4] Watts had previously spoken to The Washington Times and created controversy by criticizing "race-hustling poverty pimps"[4] as keeping African-Americans dependent on government. These remarks were viewed as critical of activist Jesse Jackson and Washington, D.C. mayor Marion Barry, and Jesse Jackson Jr. demanded a public apology.[4] Watts stated he did not speak about Barry and Jackson but about "some of the leadership in the black community."[4]

In his 1998 reelection campaign against Democrat Ben Odom, Watts faced accusations about debts, unpaid taxes and over actions in a federal bribery investigation in 1991, where he arranged to receive campaign contributions from a lobbyist for telephone companies that were investigated during Watts' membership on the Oklahoma Corporation Commission.[7] Odom used portions of a transcript to try to discredit Watts, and the accusations were widely publicized in Oklahoma.[7] Watts argued he had been exonerated from any criminal conduct and that his financial problems were a result of losses for Oklahoma oil and gas businesses during the 1980s.[7] He was re-elected with 62 percent of the vote.[14]

From 1995 until 1997, Watts was only one of two black Republicans in Congress (along with Gary Franks of Connecticut). From 1997 until 2003, Watts was the only black Republican Congressman. There would not be another until the elections of Tim Scott and Allen West in 2010.

Leadership position and retirement

editIn Congress, Watts had established himself as a "devoted conservative."[18] He had a lifetime 94 percent rating from the American Conservative Union[19] and a lifetime "liberal quotient" of 1 percent from Americans for Democratic Action,[20] and was regarded as a team player by Republicans.[11] Watts was elected House Republican Conference Chair in 1998, replacing John Boehner,[21] after a vote of 121–93.[6] Watts assumed the position in 1999[1] and was the first African-American Republican elected to a leadership post.[11]

In his leadership position, Watts opposed government regulations and President Clinton's attempt to restore the ability of the Food and Drug Administration to regulate tobacco products.[22] He voted to impeach Bill Clinton,[2] was appointed by Speaker Dennis Hastert to lead a group of House Republicans to investigate cybersecurity issues,[3] and became a member of a presidential exploratory committee for George W. Bush.[23] Watts argued for using tax reduction to improve education, job training and housing in poor urban and rural settings, and advocated letting religious institutions carry out the work.[3] Watts worked to make his party more inclusive, promoted African trade, supported historically black colleges and universities,[18] and was opposed to federal funding of embryonic stem cell research.[24]

To keep a majority of House seats in the 2000 election, Watts advised Republicans to moderate their language and criticized the party for creating the perception it favored a view of "family values that excluded single mothers."[3] Watts opposed the Confederate battle flag flying over the South Carolina State House and advised Republicans to go slowly on opposing racial quotas.[3] By then, Watts had become involved in a contest with other members of the Republican House leadership, including Tom DeLay, over control of the party's message and nearly announced retirement in early February 2000, due to strains on his family, who remained in Oklahoma during his tenure in Washington,[6] but changed his mind after consultations with constituents, Hastert, and his family.[3] He ran, despite an earlier pledge to serve not more than three terms.[25] Watts won re-nomination with 81 percent against James Odom[26] and was re-elected by his largest margin yet against Democratic candidate Larry Weatherford.[14]

After George W. Bush took office as president, Watts co-sponsored a bill to create tax incentives for charitable donations and allow religious charities to receive federal money for social programs,[27] and proposed several new tax reductions in addition to Bush's tax cut plan,[28] targeting the estate tax and marriage penalty.[29] Watts was one of ten congressional leaders taken to an undisclosed location following the September 11 attacks.[30]

In 2002, Watts stated he would not seek reelection, citing a desire to spend more time with his family,[18] but stated the decision was difficult because Rosa Parks asked him to stay.[31] Republicans argued Watts complained about the party message and the cancellation of an artillery system in his district by the Bush Administration, which Watts denied.[18] Watts supported the candidacy of Tom Cole, who won the election to fill his seat.[32]

Post-congressional career

editAfter he left Congress, Watts was appointed by President Bush to be a member of the Board of Visitors to the United States Military Academy for a term expiring December 30, 2003.[33] Watts founded a lobbying and consulting firm, J. C. Watts Companies, in Washington, D.C., to represent corporations and political groups and focus on issues he championed in Congress.[34] The John Deere Company hired Watts as lobbyist in 2006 and Watts later invested in a Deere dealership and sought financial support from United States agencies and others for a farm-related project in Senegal.[35] Watts wrote an autobiography, wrote regular opinion columns for the Las Vegas Review-Journal,[36] and joined the boards of several companies, including Dillard's,[37] Terex,[38] Clear Channel Communications,[39] and CSX Transportation,[citation needed] and served as chairman of GOPAC.[40]

Watts supported the Iraq War in 2003, stating: "America did not become the leader of the free world by looking the other way to heinous atrocities and unspeakable evils."[41] He was later hired as a political commentator by CNN[35] and following the 2006 House election, Watts argued the Republican Party had lost seats because it failed to address the needs of urban areas and did not offer a positive message. He stated: "We lost our way, pure and simple."[42]

In 2008, Watts announced he was developing a cable news network with the help of Comcast, focusing on an African-American audience,[43] and that he considered voting for Barack Obama, criticizing the Republican party for failing in outreach to the African-American community.[44] Reports showed he contributed to John McCain, but not to Obama.[45]

Watts considered running to succeed Brad Henry as Governor of Oklahoma in the 2010 gubernatorial election,[46] but declined in May 2009, citing his business and contractual obligations.[47]

On April 7, 2015, Watts joined U.S. Senator Rand Paul on stage during Paul's announcement speech for U.S. president.[48]

For most of 2016, Watts served as the president and CEO of Feed the Children (FTC). The board of directors announced his appointment on January 21.[49] On November 15, the organization and Watts announced that he was no longer serving in those roles.[50] The following April, Watts sued both FTC and its board of directors for wrongful termination. According to Watts, he was fired after uncovering rampant financial mismanagement at the charity and notifying the state's Attorney General Office of potentially illegal practices. Feed The Children denied there was any validity to Watts' claims and proceeded to file a counter-suit against him. The case was settled in 2019, after FTC agreed to drop their counter-suit and pay Watts $1 million to resolve all his claims against them.[51]

In 2019 Watts began plans to start the Black News Channel,[52] which launched on February 10, 2020, as a 24-hour news channel aimed at an African American audience.[53] The channel went out of business in April 2022, in the face of lagging cable and satellite provider subscriptions and an unsuccessful 2021 revamp that added commentators at odds with Watts's views.[54]

Writings

edit- Watts, J. C. Jr.; Watson, Chriss (2002). What Color is a Conservative? My Life and My Politics. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-093240-6.

Electoral history

edit| Year | Democrat | Votes | Pct | Republican | Votes | Pct | 3rd Party | Party | Votes | Pct | 4th Party | Party | Votes | Pct | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | David Perryman | 67,237 | 43% | J. C. Watts Jr. | 80,251 | 52% | Bill Tiffee | Independent | 7,913 | 5% | |||||||||

| 1996 | Ed Crocker | 73,950 | 40% | J. C. Watts Jr. | 106,923 | 58% | Robert Murphy | Libertarian | 4,500 | 2% | |||||||||

| 1998 | Ben Odom | 52,107 | 38% | J. C. Watts Jr. | 83,272 | 62% | |||||||||||||

| 2000 | Larry Weatherford | 54,808 | 31% | J. C. Watts Jr. | 114,000 | 65% | Susan Ducey | Reform | 4,897 | 3% | Keith B. Johnson | Libertarian | 1,979 | 1% |

Football statistics

edit| Passing | Rushing | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YEAR | CMP | ATT | CMP% | YDS | TD | INT | ATT | YDS | AVG | TD |

| 1977 | 0 | 0 | — | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 |

| 1978 | 13 | 38 | 34.2 | 227 | 2 | 4 | 42 | 204 | 4.9 | 6 |

| 1979 | 39 | 81 | 48.2 | 785 | 4 | 5 | 123 | 455 | 3.7 | 10 |

| 1980 | 35 | 78 | 44.9 | 905 | 2 | 10 | 163 | 663 | 4.1 | 18 |

| Totals | 87 | 197 | 44.2 | 1,917 | 8 | 19 | 328 | 1,322 | 4.0 | 34 |

| Passing | Rushing | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YEAR | TEAM | CMP | ATT | CMP% | YDS | TD | INT | RAT | ATT | YDS | AVG | TD | |

| 1981 | OTT | 77 | 142 | 54.2 | 957 | 3 | 11 | 50.1 | — | — | — | — | |

| 1983 | OTT | 175 | 358 | 48.9 | 3,089 | 18 | 20 | 72.3 | — | — | — | — | |

| 1984 | OTT | 189 | 360 | 52.5 | 3,052 | 21 | 23 | 74.0 | 61 | 357 | 5.9 | 1 | |

| 1985 | OTT | 236 | 439 | 53.8 | 2,975 | 12 | 25 | 60.5 | 106 | 710 | 6.7 | 1 | |

| 1986 | OTT | 66 | 127 | 52.0 | 864 | 7 | 9 | 62.6 | — | — | — | — | |

| TOR | 108 | 182 | 59.3 | 1,477 | 5 | 5 | 83.1 | — | — | — | — | ||

| Totals | — | 851 | 1,608 | 52.9 | 12,414 | 66 | 93 | 67.9 | 346 | 2,312 | 6.7 | — | |

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e "J. C. Watts, Jr.". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Fulwood, Sam III (February 22, 1999). "Republicans Cast Watts as Leader, Healer". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g Schmitt, Eric (February 21, 2000). "Public Lives; A Rising Republican Star, and Very Much His Own Man". The New York Times. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g Seelye, Katharine Q. (February 5, 1997). "G.O.P., After Fumbling in '96, Turns to Orator for Response". The New York Times. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Rhoden, William C. (December 17, 2000). "Sports of The Times; Watts Now Excels on a Different Field". The New York Times. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "J. C. Watts Jr". Office of the Clerk of the House of Representatives. Archived from the original on February 15, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Thomas, Jo (November 16, 1998). "Rising Congressional Leader Experienced in Self-Defense". The New York Times. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ a b c Fineman, Howard (November 8, 1997). "Four Eyes On The Prize". Newsweek. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007.

- ^ a b c Holmes, Steven A. (August 6, 1995). "2 Black G.O.P. Lawmakers in House Differ Slightly on Affirmative Action". The New York Times. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ a b Mullick, Rajeev. "History >> CFL Legends >> J.C. Watts". CFL.ca. Archived from the original on October 14, 2015. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Stout, David (November 19, 1998). "The Republican Transition: Man in the News – Julius Caesar Watts Jr.; A Republican of Many Firsts and Yet a Team Player". The New York Times. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ Waldman, Amy (October 1996). "The GOP's Great Black Hope". The Washington Monthly. Archived from the original on December 1, 2008. Retrieved May 16, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Verhovek, Sam Howe (October 7, 1994). "The 1994 Campaign: The Republicans; More Black Candidates Find Places on Republican Ballots". The New York Times. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e "Election Statistics". Office of the Clerk of the House of Representatives. Archived from the original on July 25, 2007. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ a b c Kuharsky, Paul (January 28, 1995). "Super Bowl XXIX; Former Football Stars Bring Game Plans to Capital". The New York Times. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ a b Holmes, Steven A. (September 26, 1996). "The States and the Issues". The New York Times. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ a b c Lewis, Neil A. (October 8, 1996). "The States and the Issues". The New York Times. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Mitchell, Alison (July 2, 2002). "Congress's Sole Black Republican Is Retiring". The New York Times. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ "2002 U.S. House Ratings". American Conservative Union. Archived from the original on February 9, 2008. Retrieved March 18, 2008. Lifetime average is given.

- ^ "Voting Records". Americans for Democratic Action. Retrieved March 19, 2009. Scores for years 1994 through 1997 were 0, 1998 as 10, and 1999 through 2002 were 0, with an average of 1.25 percent.

- ^ Seelye, Katharine Q. (November 19, 1998). "The Republican Transition: The Overview; Mix of Old and New Is to Lead House G.O.P." The New York Times. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ Clymer, Adam (March 26, 2000). "Clinton Urges Giving F.D.A. Oversight Of Tobacco". The New York Times. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ Berke, Richard L. (March 8, 1999). "Bush Tests Presidential Run With a Flourish". The New York Times. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ Hall, Mimi (July 9, 2001). "Stem-cell issue splits Republicans". USA Today. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ "Oklahoma GOP Rep. Watts to run again, despite earlier term limits pledge". CNN. January 31, 2000. Archived from the original on February 13, 2010. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ "Primary Election Results 8/22/00". Oklahoma State Election Board. Archived from the original on February 2, 2009. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ Becker, Elizabeth (March 18, 2001). "Bill on Church Aid Proposes Tax Incentives for Giving". The New York Times. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ Rosenbaum, David E. (March 15, 2001). "Republicans, In New Tactic, Offer Increase In Tax Breaks". The New York Times. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ Page, Susan; Keen, Judy (December 13, 2000). "Next chapter: Will Bush be able to govern?". USA Today. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ Raasch, Chuck; Abrams, Doug (September 11, 2001). "Top congressional leaders rushed to secure location". Gannett Company. USA Today. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ Waller, Douglas (July 10, 2002). "10 Questions For J.C. Watts". Time. Archived from the original on August 21, 2008. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ Jenkins, Ron (March 3, 2009). "Watts' Capitol visit stirs speculation". The Edmond Sun. Associated Press. Archived from the original on January 21, 2013. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ "President Bush Announced His Intention to Nominate" (Press release). Office of the Press Secretary. January 9, 2003. Retrieved March 19, 2008.

- ^ "Politics and the Economy; Former Rep. Watts Opens Consulting Firm". The New York Times. January 8, 2003. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ a b Meier, Barry (November 11, 2006). "Ex-Quarterback Thrives as Lobbyist". The New York Times. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ Watts, J. C. (March 8, 2009). "We'll all pay for this massive spending plan". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ "Dillard's, Inc. Announces Election of J.C. Watts, Jr. to Board of Directors". Business Wire. Dun & Bradstreet. March 4, 2003. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ "Terex Corporation Elects Former Congressman J.C. Watts, Jr. to Its Board". Business Wire. Dun & Bradstreet. January 8, 2003. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ "Terex Corporation Elects Former Congressman J.C. Watts, Jr. to Its Board". Business Wire. February 3, 2003. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ "GOPAC Chairman J.C. Watts, Jr. Travels to Mississippi for GOP Campaign Events on Tuesday, September 30". U.S. Newswire. September 23, 2003. Retrieved March 19, 2009.[dead link]

- ^ Espo, David (October 1, 2008). "Analysis: A vote with unforeseen consequences?". USA Today. Associated Press. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ Wolf, Richard (December 7, 2006). "Republicans of '94 revolution reflect on '06". USA Today. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ Andrews, Helena (July 17, 2008). "Watts launches African-American channel". The Politico. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ "Black Republicans consider voting for Obama". USA Today. Associated Press. June 14, 2008. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ Jones, Del (September 11, 2008). "Board diversity expands political spectrum". USA Today. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- ^ McNutt, Michael (May 7, 2009). "J.C. Watts vows to decide soon on run". The Oklahoman. Retrieved May 18, 2009.

- ^ Hoberock, Barbara (May 22, 2009). "Watts will not run for governor". Tulsa World. Retrieved May 23, 2009.

- ^ Killough, Ashley (April 7, 2015). "Rand Paul: 'I'm Putting Myself Forward as a Candidate for President'". CNN. Retrieved April 10, 2015.

The speakers included J.C. Watts, a former congressman who's African-American; state Sen. Ralph Alvarado, who's Hispanic; local pastor Jerry Stephenson, who's African American and a former Democrat; and University of Kentucky student Lauren Bosler.

- ^ "Feed the Children names J.C. Watts new president and CEO". Archived from the original on May 25, 2016. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- ^ "Leadership Change at Feed the Children". Archived from the original on December 1, 2016. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

- ^ "Feed the Children settles lawsuit with former president". The Oklahoman. July 24, 2019. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- ^ "Black News Channel Will Launch This Fall". TVSpy. April 26, 2019. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- ^ Former lawmaker, cable veteran launch 24-hour Black News Channel. UPI, February 10, 2020.

- ^ Battaglio, Stephen (March 25, 2022). "Shad Khan's Black News Channel is shutting down". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 25, 2022.

- ^ "J.C. Watts, qb". TotalFootballStats.com. Archived from the original on March 19, 2013. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

External links

edit- "J. C. Watts Companies". Official Company Website.

- "JCWattsFoundation.org". The J.C. & Frankie Watts Foundation.

- "Congressman J.C. Watts Jr". Archived congressional website from the Library of Congress.

- "J. C. Watts Jr". Office of the Clerk of the House of Representatives. Archived from the original on February 15, 2013. Retrieved March 19, 2009.

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Biography at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- Financial information (federal office) at the Federal Election Commission

- J.C. Watts at IMDb