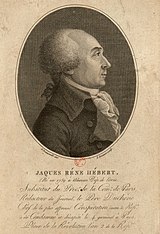

Jacques René Hébert (French: [ʒak ʁəne ebɛʁ]; 15 November 1757 – 24 March 1794) was a French journalist and leader of the French Revolution. As the founder and editor of the radical newspaper Le Père Duchesne,[1] he had thousands of followers known as the Hébertists (French Hébertistes). A proponent of the Reign of Terror, he was eventually guillotined.

Jacques Hébert | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Jacques René Hébert 15 November 1757 Alençon, Kingdom of France |

| Died | 24 March 1794 (aged 36) Paris, French First Republic |

| Cause of death | Execution by guillotine |

| Resting place | Errancis Cemetery |

| Political party | The Mountain (1792–1794) |

| Other political affiliations | Jacobin Club (1789–1792) Cordeliers Club (1792–1794) |

| Spouse | |

| Children | Virginie-Scipion Hébert (1793–1830) |

| Parent(s) | Jacques Hébert (?–1766) and Marguerite La Beunaiche de Houdré (1727–1787) |

| Residence(s) | Paris, France |

| Occupation | Journalist, writer, publisher, politician |

| Signature |  |

Early life

editJacques René Hébert was born on 15 November 1757 in Alençon, to goldsmith, former trial judge, and deputy consul Jacques Hébert (died 1766) and Marguerite Beunaiche de Houdrie (1727–1787).

Hébert studied law at the College of Alençon and went into practice as a clerk in a solicitor of Alençon, in which position he was ruined by a lawsuit against a Dr. Clouet. Hébert fled first to Rouen and then to Paris in 1780 to evade a substantial one thousand livre fine imposed for charges of slander.[2] For a while, he passed through a difficult financial time and lived through the support of a hairdresser in Rue des Noyers. There he found work in a theater, La République, where he wrote plays in his spare time, but these were never produced. Hébert was eventually fired for theft and entered the service of a doctor. It is said he lived through expediency and scams.

In 1789, he began his writing with a pamphlet La Lanterne magique ou le Fléau des Aristocrates ("The Magic Lantern, or Scourge of Aristocrats"). He published a few booklets. In 1790, he attracted attention through a pamphlet he published, and became a prominent member of the political club of the Cordeliers in 1791.[3]

Père Duchesne

editFrom 1790 until his death in 1794, Hébert became a voice for the working class of Paris through his highly successful and influential journal, Le Père Duchesne. In his journal, Hébert assumed the voice of a patriotic sans-culotte named Père Duchesne and would write first-person narratives in which Père Duchesne would often relay fictitious conversations that he had with the French monarchs or government officials.[4] Hébert and the Hébertists often expressed the view that many more aristocrats should be examined, denounced, and executed, as they argued that Revolutionary France could only be fully reborn through the elimination of its ancient and supposedly currently malignant nobility.[5] In Le Père Duchesne number 65, where he writes of his reawakening in 1790, he defines aristocrats as "enemies of the constitution" who "conspire against the nation", showing his animus against them.[6] Much of Hébert's celebrity came from his denunciations of King Louis XVI in his newspaper, as opposed to any office he may have held or his roles in any of the Parisian clubs with which he was involved.[7]

These stories encouraged violent behaviors and utilized foul and sexualized language. Père Duchesne's stories were also witty, reflective, and resonated deeply in the poorer Parisian quarters. Street hawkers would yell, "Il est bougrement en colère aujourd’hui le père Duchesne!" ("Father Duchesne is very angry today!").[citation needed]

Although Hébert did not create the image of the Père Duchesne, his use of the character helped to transform the symbolic image of Père Duchesne from that of a comical stove-merchant into a patriotic role model for the sans-culottes.[8] In part, Hébert's use of Père Duchesne as a revolutionary symbol can be seen by his appearance as a bristly old man who was portrayed as smoking a pipe and wearing a Phrygian cap.

Because he reflected both his audience's speech and dressing style, his readers listened to and followed his message. The French linguist and historian Ferdinand Brunot called Hébert, "The Homer of filth", because of his ability to use common language to appeal to general audiences.[9] In addition, Père Duchesne's appearance played into the tensions of the revolution through the sharp contrast of his clothing and portrayal as a laborer against the crown and aristocracy's formal attire.[10] Hébert was not the only writer during the French Revolution to use the image of Père Duchesne nor was he the only author in the period to adopt foul language as a way of appealing to the working class. Another writer at the time, Lemaire (fr), also wrote a newspaper entitled Père Duchêne (although he spelt it differently than Hébert) from September 1790 until May 1792 in which he assumed the voice of a "moderate patriot" who wanted to conserve the relationship between the King and the nation. Lemaire's character also used a slew of profanities and would address France's military. However, Le Père Duchesne became far more popular because it cost less than Jean-Paul Marat’s paper, L' Ami du Peuple. This made it easier to access for people like the sans-culottes.[11] The popularity was also in part, due to the Paris Commune deciding to buy his papers and distribute them to the French military for distribution to soldiers in training. For example, starting in 1792, the Paris Commune and the ministers of war Jean-Nicolas Pache and, later, Jean Baptiste Noël Bouchotte bought several thousand copies of Le Père Duchesne which were distributed free to the public and troops. This happened again in May and June 1793 when the Minister of War bought copies of newspapers in order to "enlighten and animate their patriotism". It is estimated that Hébert received 205,000 livres from this purchase.[9] The assassination of Jean-Paul Marat on July 13, 1793, who had written the bestselling paper L'Ami du peuple, allowed Le Père Duchesne to become the incontestible best-selling paper in Paris, which also played into the number of copies bought during those months.[12]

Hébert's political commentary between 1790 and 1793 focused on the lavish excesses of the monarchy. Initially, from 1790 and into 1792, Le Père Duchesne supported a constitutional monarchy and was even favorable towards King Louis XVI and the opinions of the Marquis de La Fayette. His violent attacks of the period were aimed at Jean-Sifrein Maury, a great defender of papal authority and the main opponent of the Civil Constitution of the Clergy. Although the character of Père Duchesne supported a constitutional monarchy, he was always highly critical of Marie Antoinette.[13] Knowing that the queen was an easy target for ridicule after the Diamond Necklace Affair, she became a consistent target in the paper as a scapegoat for many of France's political problems. By identifying Marie Antoinette's lavish excesses and alleged sexuality as the core of the monarchy's problems, Hébert's articles suggested that, if Marie Antoinette would change her ways and renounce aristocratic excesses, then the monarchy could be saved and the queen could return to the good will of the people. Despite his view that the monarchy could be restored, Hébert was skeptical of the queen's willingness to do so and often characterized her as an evil enemy of the people by referring to the queen as "Madame Veto" and even addressing King Louis XVI as, "drunken and lazy; a cuckolded pig".[14] Initially, Hébert was trying to not only educate his readers about the queen, but also awaken her to how she was viewed by the French public. This gave Marie-Antoinette a pivotal role in Hébert's political rhetoric; as the Revolution unfolded, she appears in fourteen percent of his newspaper articles between January 1791 and March 1794.[15] Many of the conversations that Père Duchesne carries with her in the newspaper are attempts at either showcasing her supposed nymphomania or attempts to beg her to repent and reverse her wicked ways.[16] With the king's failed flight to Varennes, his tone significantly hardened.

At the time, many writers and journalists were greatly influenced by the proclamation of martial law on 21 October 1789. It invoked various questions and patterns of Revolutionary thinking and inspired various forms of writing such as Le Père Duchesne. The law prompted multiple interpretations all of which led to what became essential Revolutionary ideals.[17]

In his newspaper, Hébert did not use himself as the prime example of the revolution. He used a mythical character called the Père Duchesne to be able to relay his message in a more subtle way. He was already well known by the people of Paris and only wanted his message to be received directly and clearly by his followers, not his enemies. Père Duchesne was a very strong, outspoken character with extremely high emotions. He constantly felt great anger but also would experience great happiness. He was never afraid to fully display exactly how he was feeling. He would constantly use foul language and other harsh words to express himself.[18][needs copy edit]

Revolutionary role

editFollowing Louis's failed flight to Varennes in June 1791, Hébert began to attack both Louis and Pope Pius VI. On 17 July, Hébert was at the Champ de Mars to sign a petition to demand the removal of King Louis XVI and was caught up in the subsequent Champ de Mars massacre by troops under the Marquis de Lafayette. This put him in the revolutionary mindset, and Le Père Duchesne adopted a populist style, deliberately opposed to the high-minded seriousness and appeal to reason expressed by other revolutionaries, to better appeal to the Parisian sans-culottes. His journalistic voice expressed separation from and violent opposition to cultured elites in favor of a popular political allegiance to radical patriotic solutions to controlling the economy and winning the war.[19] Le Père Duchesne began to attack prominent political figures like Lafayette, head of the National Guard; the deceased Comte de Mirabeau, a prominent orator and statesman; and Jean Sylvain Bailly, mayor of Paris. In a 1793 speech to the public, Hébert stated his beliefs regarding Lafayette. He noted that there were two Père Duchesnes who opposed each other deeply. The Père Duchesne that he said he identified with was the "honest and loyal Père Duchesne who has pursued traitors", while the Père Duchesne he had nothing to do with "praised Lafayette to the heavens".[20]

As a member of Cordeliers club, he had a seat in the revolutionary Paris Commune, and during the Insurrection of 10 August 1792 he was sent to the Bonne-Nouvelle section of Paris. As a public journalist, he supported the September Massacres the next month. He agreed with most of the ideals of the radical Montagnard faction, even though he was not a member of it. On 22 December 1792, he was appointed the second substitute of the procureur of the commune, and through to August 1793 supported the attacks against the Girondin faction.

In April–May 1793 he, along with Marat and others, violently attacked the Girondins. On 20 May 1793, the moderate majority of the National Convention formed the Special Commission of Twelve, a Girondin commission which was designed to investigate and prosecute conspirators. At the urging of the Twelve, on 24 May 1793, he was arrested. However, Hébert had been warned in time, and, with the support of the sans-culottes, the National Convention was forced to order his release three days later. Just four days after that, his anti-Girondin rhetoric would help lead to their ousting in the Insurrection of 31 May – 2 June. On 28 August 1793, he proposed to the Jacobins to write an address taking up the demands of the enrages, and to have it taken to the Convention by the Jacobins, the 48 sections and the popular societies, a suggestion greatly applauded by Billaud-Varenne and others, ignoring Maximilien Robespierre's warning against a riot "which would fill the aristocrats with joy".

During all this, Hébert met his wife Marie Goupil (born 1756), a 37-year-old former nun who had left convent life at the Sisters of Providence convent at Rue Saint-Honoré. Marie's passport from this time shows regular use.[citation needed] They married on 7 February 1792, and had a daughter, Virginie-Scipion Hébert (7 February 1793 – 13 July 1830).[21] During this time, Hébert had a luxurious, bourgeois life. He entertained Jean-Nicolas Pache, the mayor of Paris and Minister of War, for weeks, as well as other influential men, and liked to dress elegantly and surround himself with beautiful objects such as pretty tapestries—an attitude that can be contrasted to that of Paris Commune president Pierre Gaspard Chaumette. Where he got the financial resources to support his lifestyle is unclear; however, there are Jean-Nicolas Pache's commissions to print thousands of issues of Le Père Duchesne and his relationship to Delaunay d'Angers, mistress and wife of Andres Maria de Guzman.[who?] In February 1793, he voted with fellow bourgeois Hébertists against a Maximum Price Act, a price ceiling on grain, on the grounds that it would cause hoarding and stir resentment.

Dechristianization

editDechristianization was a movement that took hold during the French Revolution. Advocates believed that to pursue a secular society, they had to reject the superstitions of the Old Regime and, as an extension, Catholicism altogether. The trend toward secularization had already begun to take hold throughout France during the eighteenth century, but between September 1793 and August 1794, mostly during the Reign of Terror, French politicians began discussing and embracing notions of "radical dechristianization".[22] While Robespierre advocated for the right to religion and believed that aggressively pursuing dechristianization would spur widespread revolts throughout rural France, Hébert and his followers, the Hébertists, wanted to spontaneously and violently overhaul religion.[23] The writer and philosopher Voltaire was an inspiration to Hébert on this front. Like Voltaire, Hébert believed that the toleration of different religious beliefs was necessary for humanity to pass from an age of superstitions, and that traditional religion was an obstacle to this goal. Eventually, Hébert would argue that Jesus was not a demigod, but instead a good sans-culotte. Voltaire had also provided him with the basic tenets of a civic religion that would be able to replace traditional religion, which led to Hébert to being heavily involved in the movement.[24] The program of dechristianization waged against Catholicism, and eventually against all forms of Christianity, included the deportation of clergy and the condemnation of many of them to death, the closing of churches, the institution of revolutionary and civic cults, the large scale destruction of religious monuments, the outlawing of public and private worship and religious education, forced marriages of the clergy, and forced abjurement of their priesthood.[25] On 21 October 1793, a law was passed which made all suspected priests and all persons who harbored them liable to death on sight.[25]

On 10 November 1793, dechristianization reached what many historians consider the climax of the movement when the Hébertists moved the first Festival of Reason ("Fête de la Raison"), a civic festival celebrating the Goddess of Reason, from the Circus of the Palais Royale to the Cathedral of Notre Dame and reclaimed the cathedral as a "Temple of Reason".[23] On 7 June, Robespierre, who had previously condemned the Cult of Reason, advocated a new state religion and recommended that the Convention acknowledge the existence of a singular God. On the next day, the worship of the deistic Supreme Being was inaugurated as an official aspect of the Revolution. Compared with Hébert's somewhat popular festivals, this austere new religion of Virtue was received with signs of hostility by the Parisian public.[citation needed]

Clash with Robespierre, arrest, conviction, and execution

editAfter successfully attacking the Girondins, Hébert in the fall of 1793 continued to attack those whom he viewed as too moderate, including Georges Danton, Pierre Philippeaux, and Maximilien Robespierre, among others. When Hébert accused Marie Antoinette during her trial of incest with her son, Robespierre called him a fool ("imbécile") for his outrageous and unsubstantiated innuendos and lies.[26]

The government was exasperated and, with support from the Jacobins, finally decided to strike against the Hébertists on the night of 13 March 1794, despite the reluctance of Barère de Vieuzac, Collot d'Herbois and Billaud-Varenne. The order was to arrest the leaders of the Hébertists; these included individuals in the War Ministry and others.

In the Revolutionary Tribunal, Hébert was treated very differently from Danton, more like a thief than a conspirator; his earlier scams were brought to light and criticized. He was sentenced to death with his co-defendants on the third day of deliberations. Their execution by guillotine took place on 24 March 1794.[27] Hébert fainted several times on the way to the guillotine and screamed hysterically when he was placed under the blade. Hébert's executioners amused the crowd by adjusting the guillotine so that its blade stopped inches above his neck,[28] and it was only after the fourth time the lever (déclic) was pulled that he was actually beheaded. His corpse was disposed of in the Madeleine Cemetery. His widow was executed twenty days later on 13 April 1794, and her corpse was disposed of in the Errancis Cemetery.

The importance of Hébert's execution was known by everyone involved in the revolution, including the Jacobins. Louis Antoine de Saint-Just, a prominent Jacobin leader, noted that following his execution, "the revolution is frozen",[29] demonstrating how central Hébert and his followers, a large portion of sans-culottes, were to the longevity and success of the revolution.

Influence

editIt is difficult to completely ascertain the extent to which Hébert's publication Le Père Duchesne impacted the outcomes of political events between 1790 and 1794. French revolutionary historians such as Jean-Paul Bertaud, Jeremy D. Popkin, and William J. Murray each investigated French Revolutionary press history and determined that while the newspapers and magazines that one read during the revolution may have influenced their political leanings, it did not necessarily create their political leanings. One's class, for example, could be a significant determinant in directing and influencing one's political decisions. Therefore, Hébert's writings certainly influenced his audience to often dramatic extent, but the sans-culottes were but one element in a complex political mix, meaning that it is difficult to determine in what ways his writing changed the political outcomes of the French Revolution.[30] That being said, his wide readership and voice throughout the Revolution means that he was a significant public figure, and Le Père Duchesne's ability to influence the general population of France was indeed notable.

Gallery

edit-

Illustration from Le Père Duchesne broadsides

-

Letter by Jacques Hébert to citizen Pierre-François Palloy

References

edit- ^ Doyle, William (1989); The Oxford History of the French Revolution; Clarendon Press; ISBN 0-19-822781-7. See p.227."

- ^ Colwill, Elizabeth. "Just Another 'Citoyenne?' Marie-Antoinette on Trial, 1790-1793". History Workshop (28): 63–87. JSTOR 4288925.

- ^ Chisholm 1911.

- ^ Sonenscher, Michael. "The Sans-culottes of the Year II: Rethinking the Language of Labour in Revolutionary France". Social History Vol. 9 No. 3 (1984): 326.

- ^ Weber, Caroline (2003). "Chapter 2: The Terror That Speaks: The Unspeakable Politics of Robespierre and Saint-Just" (PDF). Terror and Its Discontents: Suspect Words in Revolutionary France. University of Minnesota Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-8166-9333-7. JSTOR 10.5749/j.cttts898.6.

- ^ Hébert, Jacques-René (1790). "The Reawakening of Père Duchesne". Père Duchesne. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ McNamara, Charles B. (1974). THE HEBERTISTS: STUDY OF A FRENCH REVOLUTIONARY "FACTION" IN THE REIGN OF TERROR, 1793-1794 (PhD). Fordham University.

- ^ Colwill, Elizabeth (1989). "Just Another "Citoyenne?" Marie-Antoinette on Trial, 1790–1793". History Workshop. 28 (28): 65. doi:10.1093/hwj/28.1.63. JSTOR 4288925.

- ^ a b Gilchrist, John Thomas (1971). The Press in The Press in the French Revolution. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 21.

- ^ Landes, Joan. "More than Words: The Printing Press and the French Revolution". Review of Revolution in Print: The Press in France, by Robert Darton, Daniel Roche; Naissance du Journal Revolutionnaire, by Claude Labrosse, Pierre Retat; La Revolution du Journal, by Pierre Retat; Revolutionary News; The Press in France, by Jeremy D. Popkin. Eighteenth-Century Studies Vol. 25 No. 1 (1991): 85–91.

- ^ Colwill, Elizabeth. "Just Another 'Citoyenne?' Marie-Antoinette on Trial, 1790-1793". History Workshop (28): 63–87. JSTOR 4288925.

- ^ Doyle, William (1989); The Oxford History of the French Revolution; Clarendon Press; ISBN 0-19-822781-7. See p.250: "Hébert’s Père Duchesne, written in the oath-strewn vernacular, became the undisputed best-selling paper in Paris once Marat was silenced."

- ^ Colwill, Elizabeth. "Just Another 'Citoyenne?' Marie-Antoinette on Trial, 1790-1793". History Workshop (28): 63–87. JSTOR 4288925.

- ^ Colwill, Elizabeth (1989). "Just Another 'Citoyenne?' Marie-Antoinette on Trial, 1790–1793". History Workshop Journal. 28 (28): 72–73. doi:10.1093/hwj/28.1.63.

- ^ Colwill, Elizabeth. "Just Another 'Citoyenne?' Marie-Antoinette on Trial, 1790-1793". History Workshop (28): 63–87. JSTOR 4288925.

- ^ Kaiser, Thomas. "Who’s Afraid of Marie-Antoinette? Diplomacy, Austrophobia, and the Queen." French History, Vol. 14 No. 3 (2000): 241–271.

- ^ Neusy, Aurélie (1 April 2011). "Opinions et réflexions sur la loi martiale dans la presse et les pamphlets (1789‑1792)". Annales Historiques de la Révolution Française (in French). 360 (360): 27–48. doi:10.4000/ahrf.11639. ISSN 0003-4436.

- ^ Beik, Paul (1970). "November, 1793: Père Duchesne, His Plebeian Appeal". The French Revolution. pp. 271–276. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-00526-0_39. ISBN 978-1-349-00528-4.

- ^ Colwill, Elizabeth. "Just Another 'Citoyenne?' Marie-Antoinette on Trial, 1790-1793". History Workshop (28): 63–87. JSTOR 4288925.

- ^ Roux, Jacques; Cloots, Anacharsis; Hébert, Jacques-René; Maréchal, Sylvain (2018). "Jacques Hébert". In Abidor, Mitchell (ed.). The Permanent Guillotine: Writings of the Sans-Culottes. Oakland, CA: PM Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-1-629-63406-7.

- ^ Nicolle, Paul (October–December 1947). "La Fille d'Hébert. Son parrain. — La descendance du Père Duchesne". Annales historiques de la Révolution française. 19 (108): 326–332. JSTOR 41925452.

- ^ Chartier, Roger (1991). The Cultural Origins of the French Revolution. Duke University Press. pp. 105–106.

- ^ a b Mayer, Arno J. (2000). The Furies: Violence and Terror in the French and Russian Revolutions. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 441–442. ISBN 9780691048970.

- ^ Gliozzo, Charles A. (September 1971). "The Philosophes and Religion: Intellectual Origins of the Dechristianization Movement in the French Revolution". Church History. 40 (3): 273–283. doi:10.2307/3163003. JSTOR 3163003. S2CID 162297115. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ a b Latreille, A. (2003). "French Revolution". New Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 5 (Second Ed. 2003 ed.). Thomson-Gale. pp. 972–973. ISBN 978-0-7876-4004-0.

- ^ Joachim Vilate (1795) Causes secrètes de la révolution du 9 au 10 thermidor, p. 12-13

- ^ Doyle (1989); p.270. |"The trial took place on 21–4 March, its result a foregone conclusion. Among those who went to the scaffold with Pere Duchesne on the afternoon of the twenty-fourth were Vincent, Ronsin, and the leader of section Marat, Momoro."

- ^ Page 27 BBC History Magazine, September 2015

- ^ Roux, Jacques; Cloots, Anacharsis; Hébert, Jacques-René; Maréchal, Sylvain (2018). "Introduction". In Abidor, Mitchell (ed.). The Permanent Guillotine:Writings of the Sans-Culottes. Oakland, CA:PM Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-629-63406-7.

- ^ Jeremy D., Popkin (1990). "The Press and the French Revolution after Two Hundred Years". French Historical Studies. 16 (3): 688–670. doi:10.2307/286493. JSTOR 286493.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 167. The 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica, in turn, gives the following references:

- Louis Duval, "Hébert chez lui", in La Révolution Française, revue d'histoire moderne et contemporaine, t. xii. and t. xiii.

- D. Mater, J. R. Hibert, L'auteur du Père Duchesne avant la journée du 10 août 1792 (Bourges, Comm. Hist. du Cher, 1888).

- François Victor Alphonse Aulard, Le Culte de la raison et de l'être suprême (Paris, 1892).