The Flood Building is a 12-story highrise in the downtown shopping district of San Francisco, California. It is located at 870 Market Street on the corner of Powell Street, next to the Powell Street cable car turntable, Hallidie Plaza, and the Powell Street BART Station entrance. Designed by Albert Pissis and completed in 1904 for James L. Flood, son of millionaire James Clair Flood, it is one of the few major buildings in San Francisco that survived the 1906 earthquake and fire. As of 2024[update], it is still owned by the Flood family.[3]

| James C. Flood Building | |

|---|---|

Flood Building in 2017 | |

| Alternative names | James L. Flood Building 870 Market Street |

| General information | |

| Type | Commercial offices Retail space |

| Architectural style | Beaux-Arts |

| Location | 870 Market Street San Francisco, California |

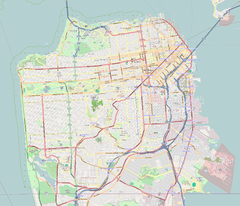

| Coordinates | 37°47′06″N 122°24′27″W / 37.7849°N 122.4074°W |

| Completed | 1904 |

| Cost | US$1.5 million |

| Owner | The James C. Flood Family Mary E Stebbins Trust |

| Management | Wilson Meany Sullivan |

| Technical details | |

| Structural system | Steel frame |

| Floor count | 12 |

| Floor area | 293,000 sq ft (27,200 m2) |

| Lifts/elevators | 5 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Albert Pissis |

| Developer | James L. Flood |

| Designated | 1982[1] |

| Reference no. | 154 |

| References | |

| [2] | |

Building

editJohn King, the architecture critic of the San Francisco Chronicle, has described the Flood Building as "twelve stories of orderly pomp with a rounded prow that commands the corner of Powell and Market Streets ... Every detail is rooted and right, from the tall storefronts that beckon cable car daytrippers to the baroque cliff of the sandstone façade with its deep-chiseled windows."[4][5] Baroque revival in style, it is a steel-frame building clad in grey Colusa sandstone. A lobby with red marble columns traverses the building from Market to Ellis Street. The wedge-shaped office floors surround a lightwell; the corridors have white marble flooring and veined white marble walls, and have retained their wooden doors with openable transom windows.[3]

History

editThe site formerly housed Baldwin's Hotel and Theatre, which was destroyed by fire in 1898.[3][6] It was later purchased by James L. Flood, who constructed the building as a tribute to his father, James Clair Flood, the Comstock Lode millionaire).[6] Designed by Albert Pissis, it opened in 1904 as San Francisco's largest building.[3] In 1906, it was one of the few major buildings to survive the San Francisco earthquake and the fire that followed;[3] full restoration of the interior took two years.[6]

By World War II, the building had become medical and dental offices.[6] In 1950, the Flood family accepted a proposal from the F. W. Woolworth Company to replace it with a modern three-story store, which would revert to the family on the expiration of a 50-year lease. Instead, after the tenants had been evicted in preparation for demolition, the building was requisitioned by the Navy for logistics purposes during the Korean War, reverting to the Flood family after the war ended in 1953. The Navy returned the retail floors to the family, and in 1952 Woolworth's opened a store in the basement and on the first and second floors, on a 40-year lease.[3][6][7]

The building was renovated in the 1990s[3][8] at a cost of $15 million, and a bust of James L. Flood by his daughter Mary Ellen Flood Stebbins was installed in the lobby.[7]

Tenants

editThe Southern Pacific Railroad company had its headquarters in the Flood Building from 1907 until 1917 when it moved to its own building, now at One Market Plaza.[9]

The Pinkerton Detective Agency had an office on the third floor, where it employed the novelist Dashiell Hammett as an operative; Hammett located his fictional Continental Detective Agency in the building.[10]

Other office tenants have included the Teamsters and the Internal Revenue Service.[6] On the afternoon of January 27, 1975, the two-year anniversary of the ceasefire of the Vietnam War, demonstrators staged a takeover of the Consulate of South Vietnam, located above Woolworths.[11] [12] Until 2002, the building housed the consulate of Mexico; in 2003, eight consulates remained,[6] in 2020, two, those of Nicaragua and Chile.[7] In 2024, the Market Street Railway and Circus Bella have their offices there.[3]

From 1952 to 1993 the Woolworth's store at the base of the Flood Building was the largest in the chain; its size was then reduced, occupying only the basement level, and it closed in 1997.[8] More recently, flagship stores for Gap, Urban Outfitters, and Anthropologie have been located in the building's retail space. The Gap store closed in 2020;[3][13] As of July 2024[update], Following COVID-19, Urban Outfitters is the only first-floor retail tenant, and there are a number of office vacancies.[3]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "City of San Francisco Designated Landmarks". City of San Francisco. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014.

- ^ "Emporis building ID 118775". Emporis. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j John King (July 26, 2024). "S.F.'s Flood Building is a 120-year-old icon. Now it's facing its toughest challenge in decades". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved July 27, 2024.

- ^ John King (February 15, 2009). "Flood Building: Every detail is rooted, right". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ John King (2011). Cityscapes: San Francisco and its Buildings. Heyday. ISBN 978-1597141543.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Patricia Yollin (July 4, 2003). "Flood of Memories". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved July 27, 2024.

- ^ a b c Steve Rubenstein (February 22, 2020). "San Francisco's James Flood, descendant of Silver King, dies at 80". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved July 27, 2024.

- ^ a b Kenneth Howe (July 18, 1997). "Dime Store Era Comes To an End / Woolworth closing 400 outlets". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved July 27, 2024.

- ^ Don L. Hofsommer (1986). The Southern Pacific, 1981–1985. College Station: Texas A & M University Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-60344-127-8.

- ^ Audrey Medina (January 16, 2011). "5 places for finding the stuff of film noir". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved July 27, 2024.

- ^ The Conspiracy, magazine of the National Lawyers Guild, Volume 5, Number 4, page 6, March 1975, San Francisco, CA, https://content.wisconsinhistory.org/digital/collection/p15932coll8/id/15581/

- ^ (1975, January 28). San Francisco Chronicle, p. 1. Available from NewsBank: San Francisco Chronicle Historical Archive: https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/news/document-view?p=EANX-NB&docref=image/v2%3A142051F45F422A02%40EANX-NB-1516A427EC6F7C28%402442441-151473F7E8B8BA5C%400-151473F7E8B8BA5C%40.

- ^ Shwanika Narayan (August 18, 2020). "Most San Francisco Gap stores close permanently, including Market Street flagship". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved July 27, 2024.

External links

edit- Media related to Flood Building at Wikimedia Commons

- Official website