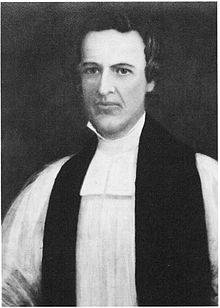

James Hervey Otey (January 27, 1800 – April 23, 1863) was a Christian educator, author, and the first Episcopal Bishop of Tennessee. He established the Anglican church in the state, including its first parish churches and what became the University of the South.[1]

The Right Reverend James Hervey Otey S.T.D., D.D., LL.D. | |

|---|---|

| Bishop of Tennessee | |

| |

| Church | Episcopal Church |

| Diocese | Tennessee |

| Elected | June 29, 1833 |

| In office | 1834–1863 |

| Successor | Charles Todd Quintard |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | June 7, 1827 by John Stark Ravenscroft |

| Consecration | January 14, 1834 by William White |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 27, 1800 |

| Died | April 23, 1863 (aged 63) Memphis, Tennessee, United States |

| Buried | St John's Churchyard, Ashwood |

| Nationality | American |

| Denomination | Anglican |

| Parents | Isaac Otey & Elizabeth Mathews |

| Spouse | Elizabeth Davis Pannill |

Early and family life

editJames Hervey Otey was born January 27, 1800, on a plantation near Fancy Farm in Bedford County, Virginia to Major Isaac Otey and Elizabeth Mathews.[2][3][4] His paternal grandfather, Capt. John Armistead Otey, had served in the American Revolutionary War. Major Otey farmed using enslaved labor as well as represented Bedford County in the Virginia House of Delegates (part-time) for many terms beginning (1798-1804, 1805–1812),[5] before attaining his military rank in the War of 1812.[6] In 1807, Major Isaac Otey purchased Fancy Farm (including a distillery and grist mill) from the estate of Andrew Donald, a Scottish merchant who had built that plantation but died before his sons reached legal age.[7] Major Otey or his heir of the same name also served as executor of the will of Thomas Dillard, who owned Fancy Farm 1817–1820.[8] His son Isaac Otey Jr. would also operate plantations and serve five terms in the Virginia House of Delegates representing Bedford County.[9] Isaac Otey purchased Mount Prospect plantation and other properties on the Otter River (altogether about 3000 acres) in 1818, then sold 1540 acres to his son John M. Otey in 1820[10] James Otey was among the youngest of his father's twelve children, and received a private education at the New London Academy at the county seat (then called Liberty, Virginia, now Bedford), before attending the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. In addition to receiving an A.B. and B.D., Otey was named a Bachelor of Belles Lettres".[11]

After graduating in 1820, Otey became a tutor in Greek and Latin at his alma mater. Following his marriage in 1821 to Elizabeth Davis Pannill, daughter of William Pannill and Martha Mitchell of Petersburg, Virginia, Otey moved to Maury County, Tennessee and opened a boys' school.[12] The Oteys would have at least six children. Their household also included enslaved people, as did other related families back in Virginia. In the 1840 federal census, Otey owned three enslaved people.[13]

Ministry

editHowever, Otey soon left Tennessee, having accepted a position as President of Warrenton Academy in North Carolina. While in Warrenton, Otey was baptized and confirmed in The Episcopal Church by bishop Ravenscroft. He became a deacon in 1825 and priest in 1827.

Otey then returned to Franklin and organized Tennessee's first Episcopal church there in the Masonic Lodge. His later-famous pupils included Matthew F. Maury, future Confederate General Braxton Bragg, and Thomas Bragg.[14] Otey also established several other churches and on July 1, 1829, established the Episcopal Diocese of Tennessee at Nashville.[15] Otey was elected the missionary diocese's first bishop in June 1833 and was consecrated at Christ Church, Philadelphia, the following January. Following his election, Otey also took charge of the Diocese of Mississippi and was missionary bishop for Arkansas and the Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). He traveled for months at a time across the extensive region, establishing new churches and preaching the Gospel.[16]

Fervently interested in Christian education, Otey helped organize schools at Ashwood, Jackson and Columbia, Tennessee, the later with the Rev. Leonidas Polk, future Bishop of Louisiana and Confederate general. Bishop Otey's 30-year dream for a "Literary and Theological Seminary" for the region were realized when the University of the South at Sewanee, in southeastern Tennessee, was established in 1857.

Otey lived at "Mercer Hall" in Columbia from 1835 to 1852, when he relocated to Memphis, Tennessee, where in 1863 he died.[17] He had opposed coercion as the Civil War began, and declined to attend the organizational meetings of the Confederate Episcopal Church.[18] After the Civil War, he was re-buried at St. John's Church at Ashwood in Maury County.

References

edit- ^ Appleton's Cyclopedia vol. IV, p. 604

- ^ The Churchman. George S. Mallory. 1898.

- ^ Boots, John R. (1970). The Mat(t)hews family: an anthology of Mathews lineages. The University of Wisconsin — Madison

- ^ Parker, Lula Jeter (1988). Parker's History of Bedford County, Virginia. Bedford, Virginia: Hamilton's. p. 128. ISBN 0960859845

- ^ Cynthia Miller Leonard, Virginia General Assembly, 1619-1978 (Richmond: Library of Virginia 1978) pp. 211, 215, 219, 223, 227, 231, 235, 243, 247, 251, 256, 260, 265, 269

- ^ Parker p. 109

- ^ Parker p. 109

- ^ Fancy Farm NRIS

- ^ Leonard pp. 303, 312, 317, 322, 326

- ^ Parker pp. 11-112

- ^ Parker p. 128

- ^ Davies-Rodgers, E. (1983). "James Hervey Otey". Heirs Through Hope: The Episcopal Diocese of West Tennessee: 36.

- ^ 1840 U.S. Federal Census for Maury County, Tennessee, pp. 57 and 58 of 217

- ^ Parker p. 128

- ^ McDonald, M. S. (1975). "The Episcopate of James Hervey Otey". White Already to Harvest: The Episcopal Church in Arkansas, 1838-1971: 21.

- ^ Buchanan, J. S. (1939). "The Episcopate of James Hervey Otey". Chronicles of Oklahoma. 17: 266.

- ^ "Death of Bishop Otey". The Weekly Standard. Raleigh, North Carolina. May 20, 1863. p. 1. Retrieved June 15, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Appleton's

- Richard Quin ([n.d.]). James Hervey Otey. In: The Tennessee Encyclopaedia of History and Culture. Nashville, Tennessee: Tennessee Historical Society. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. – please see talk