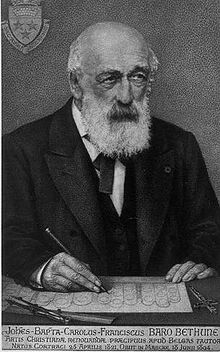

Jean-Baptiste Bethune (April 25, 1821 – June 18, 1894) was a Belgian architect, artisan and designer who played a pivotal role in the Belgian and Catholic Gothic Revival movement. He was called by some the "Pugin of Belgium", with reference to the influence on Bethune of the English Gothic Revival architect and designer, Augustus Pugin.[1]

Jean-Baptiste Charles François Baron Bethune | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 25 April 1821 Kortrijk, Belgium |

| Died | 18 June 1894 (aged 73) Marke, Belgium |

| Nationality | Belgian, |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Buildings | Loppem Castle (in collaboration with E.W. Pugin) Maredsous Abbey |

Life

editJean Bethune was the eldest son of baron Felix Bethune, a textile merchant in Kortrijk and his wife, Julie de Renty (1791–1856), from Lille.[2] His family was Flemish of French origin. He and his relatives were fervent Catholics, and many were active in politics and civil service. The family which was originally called "Bethune" was in 1845 granted nobility by the Belgian King and added the preposition "de" (some of them took the name "de Béthune-Sully"), in the 20th century, to underline their noble status. However, this great architect never used the particule.

His Irish home teacher Michel Breen first introduced him to history and antiquity, and more particularly Gothic art as an expression of Christianity. Bethune first studied law at the Catholic University of Leuven from 1837 to 1842, but did not complete his studies. It was at Leuven that he discovered the writings of Augustus Welby Pugin, the advocate of Gothicism in England and another enthusiastic Catholic.[2]

He received his basic artistic training at the Academy of Fine Arts in Kortrijk (his teachers were L. Verhaegen and Jules Victor Génisson). He took courses in landscape painting with Paul Lauters in Brussels, while the sculptor C. H. Geerts (1807–1855) – himself a pioneer of the Gothic Revival style – made him familiar with sculpture. In June 1843 he visited England, where he stayed until October. While there he met Pugin. Bethune lived in Bruges (1845–1859) where he served as the dean of the Noble Confraternity of the Holy Blood.[2]

In June 1845, Béthune embarked on a career in public service and became secretary to the West-Flemish governor. In 1848 Béthune married Emilie van Outryve d'Ydewalle in Bruges. He served as a member of the Provincial Council of West Flanders (1848–1858), supported by his father-in-law. Bishop Jean-Baptiste Malou introduced him to the English artists' colony in Bruges.[3]

The encounter with Pugin and his creations further stimulated Bethune's interest in architecture and applied arts. In imitation of Pugin and his followers, Bethune developed the idea that an artistic revival of the arts of the Christian world of the Middle Ages could inspire a new profoundly Christian/Catholic society. At home, Bethune was encouraged by Canon C. Carton to become involved in the creation of genuinely "Christian Art". Gradually he began to make designs himself. He returned to England in 1850 and apprenticed for several months with John Hardman, Pugin's stained-glass manufacturer, in Birmingham. Inspired by this, Bethune started a workshop for stained glass windows in 1854, together with his brother-in-law Eugène van Outryve d'Ydewalle , in the Hoogstraat in Bruges.[3]

In 1854, Bethune designed the interior of the Chapel of the Holy Blood in Bruges.[4] In 1857 Bethune received an important commission from the Ghent textile manufacturer Joseph de Hemptinne, shifting his field of activity to Ghent and East Flanders. In 1858 he moved with his studio from Bruges to Sint-Denijs-Westrem.[3]

In 1862, he was a co-founder of the "Saint Luke schools" (Sint-Lucasscholen) influenced by the architectural and decorative theories of Viollet le Duc.[5] These schools were opened as a Catholic counterpart to the official Academies and trained architects in the religious spirit of the Gothic tradition. The first permanent Saint Luke school opened in Ghent in 1863. These schools also offered an education for artisans that could work with stained-glass, wood carving, painting, gold- and silverwork... The aim was to train craftsmen that could cope with the overall decoration of a newly built, fully decorated, Gothic church. As a teacher and as a patron of the archaeological society of the "Gilde de Saint-Thomas et de Saint-Luc" founded in 1863, Bethune had a decisive influence on the evolution of the Gothic Revival style in Belgium. Among those he taught or influenced were the architects Joris Helleputte and Louis Cloquet. Abroad, he maintained contacts and was appreciated by contemporaries such as Pierre Cuypers, Edward Welby Pugin, August Reichensperger and Edward von Steinle.

Bethune also worked closely with Henri and Jules Desclée, creating illustrations for their print houses, such as the Society of St. John the Evangelist.[6]

Work

editBethune was increasingly fascinated by (neo) gothic and became one of the pioneers of this art movement in Belgium. In his architectural creations, Bethune adopted the formal vocabulary of the typical late medieval brick architecture of Flanders, and specifically Bruges. Through his influence and teaching he introduced this stance by many of his followers. This, together with his strong Catholic inspiration and his association with the Gothic Revival movement in England, marks the difference between his school and the Neo-Gothic architecture advocated in Belgium by the Academies.

Apart from architectural projects, his very extensive oeuvre includes designs for practically all the plastic and decorative arts. From Belgium, his designs found their way to most other European countries. The quality of his work can best be judged from his integrated building projects, which combine all forms of art, such as Loppem Castle, the complex in Vivenkapelle (including a church, a presbytery and a convent school) and the large complex of Maredsous Abbey. Bethune's designs show a strong architectural, archaeological and didactic character. With his stained-glass windows (f.e. in the cathedrals of Bruges, Ghent, Antwerp, and Tournai), his mural paintings, (f.e. in the castle of Maaltebrugge, 1862–1864), and his mosaics (Aachen Cathedral 1872) he contributed significantly to the revival of these art forms. Among his most important realisations as a designer of gold- and silverwork are the Belgian Tiara offered to pope Pius IX in 1871, the Charles-the-Good Shrine in St. Salvator's Cathedral in Bruges (1883), the Saint Lambert Shrine in the St. Paul's Cathedral in Liège (1884).

List of works

editArchitecture

editAll architectural projects include the designs for decoration and furnishings.

- Loppem Castle, 1859–1862.

- Church, presbytery and schools in Vivenkapelle near Damme, 1860–1870.

- Maredsous Abbey, 1872–1889.

- Church Sacré Coeur of "Le Trieu" in Courrière, 1872–1873.

- Church of the beguinage of Sint-Amandsberg near Ghent, 1874.

- Chapel of Our Lady at the Jesuit Convent 'Oude Abdij" in Drongen, 1877.

- Convent of the "Clarisses de l'Epeule" in Roubaix, France

- Ecole de Saint-Luc (Saint-Luke school) in Tournai

- Church Saint-Joseph in Roubaix, France

- Church of Fontenoy, Antoing, Belgium

Designs for applied arts

edit- Design for a sculpture of the Resurrection by Leonard Blanchaert in Holy Cross Church, Heusden, (1865)

- Design for the Belgian Tiara donated to Pope Pius IX in 1871.

- Design for the mosaic decoration of the dome of Aachen Cathedral (executed by the workshop of Antonio Salviati), 1879–1881.

- Funeral monument of Monseigneur Gravez, bishop of Namur, in Namur

- Funeral monument of the Lefèvre family in Sclayn

- Design for a Shrine to contain the relics of Charles I, Count of Flanders, in Bruges Cathedral, 1883–1885

- Design for the Shrine of Saint Lambert in the Cathedral of Liège, 1884.

- Church of Dinant: Main altar and other religious furniture.

- Interior decoration in the Castles of, Denée, Gesves and Spontin

Family name

editDuring his lifetime, Jean Bethune never used the prefix 'de' in his family name. It was no longer in use in the family since the early 18th century. Only after his death, members of the family, including his son Jean-Baptiste (1853–1907) obtained in 1904 the 'de' addition, which was made retroactive into the person of Jean-Baptiste Bethune (1722–1799) and all his descendants. It thus also applied to Jean Bethune. It is therefore acceptable to give his name with or without the prefix, although in their genealogies, the members of the family do not use the prefix regarding ancestors who did not use it in their lifetime.

Another part of the family succeeded in adding officially 'Sully' to their name. There is, however, no connection between them and the French princely family Bethune-Sully.

References

edit- ^ William Henry James Weale, in: Building News, XXXVI, 1879, p. 350

- ^ a b c "Jean-Baptiste C. F. (de) Béthune", Bruges Public Library

- ^ a b c "J.B. Bethune", De Stichting de Bethune

- ^ Snauwaert, Livia (2005). Gids voor architectuur in Brugge (in Dutch). Tielt: Lannoo Uitgeverij. pp. 58–60. ISBN 90-209-4711-7.

- ^ Folville, Xavier (January 1950). "Modernisme Eclectisme - Cinquante ans de dessins d'architecture à l'École Saint-Luc Liège". Université de Liège. p. 9.

- ^ Vermeersch, A. "Henri and Jules Desclee". Catholic Answers. Retrieved 13 September 2024.

This article is featured on Catholic Answers, but was taken from the Catholic Encyclopedia, which was published in 1912.

Bibliography

edit- Coomans, Thomas, "Pugin Worldwide. From Les Vrais Principes and the Belgian St Luke Schools to Northern China and Inner Mongolia", in: Timothy Brittain-Catlin, Jan De Maeyer & Martin Bressani (eds), Gothic Revival Worldwide: A.W.N. Pugin's Global Influence (KADOC Artes 16), Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2016, pp. 156–171 [ISBN 978-9462700918].

- De Maeyer, Jan (ed.), De Sint-Lucasscholen en de neogotiek, (Kadoc-Studies, 5), Leuven, 1988.

- Devliegher, Luc, "Béthune, Jean de", in: Nationaal Biografisch Woordenboek, 1, Brussels, 1964, col. 188–191.

- Helbig, Jules, Le Baron Bethune, fondateur des Écoles Saint-Luc. Étude biographique, Lille-Bruges, 1906.

- Sabbe, D., "J.B. Bethune, promotor van de neogotische beweging", in: Handelingen van de Koninklijke Geschied- en Oudheidkundige Kring van Kortrijk, 68, 1979, p. 267–355.

- Uytterhoeven, J., "Baron Jean-Baptiste de Béthune en de neogotiek", in: Handelingen van de Koninklijke Geschied- en Oudheidkundige Kring van Kortrijk, 34, 1965, pp. 3–101.

- Van Caloen, Véronique, Jean Van Cleven & Johan Braet (eds), Le château de Loppem, Zedelgem, 2001.

- Van Cleven, Jean, Frieda Van Tyghem & al., De Neogotiek in België, Tielt, 1994.

- Vandenbreeden, Jos & Françoise Dierkens-Aubry, The 19th Century in Belgium. Architecture and Interiors, Tielt, 1994.

External links

edit- http://www.stichtingdebethune.be/ official website of the de Bethune family archive and library

- Jean-Baptiste Bethune in ODIS - Online Database for Intermediary Structures Archived 28 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine