Jeanette "Jennie" Spencer-Churchill[1] CI RRC DStJ (née Jerome; 9 January 1854[2] – 29 June 1921), known as Lady Randolph Spencer-Churchill,[a] was an American-born British socialite, the wife of Lord Randolph Churchill, and the mother of British prime minister Winston Churchill.

Jeanette Spencer-Churchill | |

|---|---|

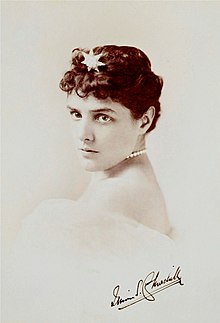

Photograph by José María Mora, 1880s | |

| Born | Jeanette Jerome 9 January 1854 Brooklyn, New York State, U.S. |

| Died | 29 June 1921 (aged 67) London, England |

| Buried | St Martin's Church, Bladon |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Issue | Sir Winston Churchill Jack Churchill |

| Father | Leonard Jerome |

| Mother | Clarissa Hall |

Early life

editJennie[b] Jerome was born in the Cobble Hill section of Brooklyn in 1854,[3] the second of four daughters (one died in childhood) of financier, sportsman, and speculator Leonard Jerome and his wife Clarissa (always called Clara[4]), daughter of Ambrose Hall, a landowner. Jerome's father was of Huguenot extraction, his forebears having emigrated to America from the Isle of Wight in 1710.[5] Hall family lore insists that Jennie had Iroquois ancestry through her maternal grandmother;[6] however, there is no research or evidence to corroborate this.[7]

She was raised in Brooklyn,[c] Paris, and New York City. She had two surviving sisters, Clarita (1851–1935) and Leonie (1859–1943). Another sister, Camille (1855–1863) died when Jennie was nine.[8]

There is some disagreement regarding the time and place of her birth. A plaque at 426 Henry St. gives her year of birth as 1850, not 1854. However, on 9 January 1854, the Jeromes lived nearby at number 8 Amity Street (since renumbered as 197). It is believed that the Jeromes were temporarily staying at the Henry Street address, which was owned by Leonard's brother Addison, and that Jennie was born there during a snowstorm.[9]

She was a noted beauty; an admirer, Lord d'Abernon, said that there was "more of the panther than of the woman in her look."[10]

Personal life

editJennie was a talented amateur pianist, having been tutored as a girl by Stephen Heller, a friend of Chopin. Heller believed that his young pupil was good enough to attain "concert standard" with the necessary "hard work", of which, according to author Mary S. Lovell, he was not confident she was capable.[11]

In 1909, when American impresario Charles Frohman became sole manager of The Globe Theatre, the first production was His Borrowed Plumes, written by Jennie. Although Mrs Patrick Campbell produced and took the lead role in the play, it was a commercial failure. It was at this point that Campbell began an affair with Jennie’s then husband, George Cornwallis-West.[12]

Jennie served as the chair of the hospital committee for the American Women's War Relief Fund starting in 1914.[13][14] This organization helped fund and staff two hospitals during World War I.[15]

First marriage

editJennie Jerome was married for the first time on 15 April 1874, aged 20, at the British Embassy in Paris, to Lord Randolph Churchill, the third son of John Winston Spencer-Churchill, 7th Duke of Marlborough and Lady Frances Anne Vane.[16] The couple had met at a sailing regatta on the Isle of Wight in August 1873, having been introduced by the Prince of Wales, the future King Edward VII.[17]

Although they became engaged within three days of this initial meeting, the marriage was delayed for months while their parents argued over settlements.[18] By this marriage, she was properly known as Lady Randolph Churchill and would have been addressed in conversation as Lady Randolph.

The Churchills had two sons: Winston (1874–1965), and John (1880–1947). Winston, the future prime minister, was born less than eight months after the marriage. Amongst his biographers, there are varied opinions on whether he was conceived before the marriage (notably William Manchester), or born two months prematurely after Lady Randolph "had a fall."[19] When asked about the circumstances of his birth, Winston Churchill replied: "Although present on the occasion, I have no clear recollection of the events leading up to it."[18] Rumours also circulated about the parentage of Winston's younger brother John, as Lady Randolph's sisters initially believed that the biological father of the second son, John (1880–1947) was Evelyn Boscawen, 7th Viscount Falmouth,[20] although that was mostly discredited due to the boys' striking likeness to Randolph Churchill and to each other.

Lady Randolph is believed to have had numerous lovers during her marriage, including the Prince of Wales, Milan I of Serbia, Prince Karl Kinsky, and Herbert von Bismarck.[21]

As was the custom of the day in her social class, Lady Randolph played a limited role in her sons' upbringing, relying largely upon nannies, especially Elizabeth Everest. Winston worshipped his mother, writing her numerous letters during his time at school and begging her to visit him, which she rarely did. He wrote about her in My Early Life: "She shone for me like the evening star. I loved her dearly – but at a distance." After he became an adult, they became good friends and strong allies, to the point where Winston regarded her almost as a political mentor, and “on even terms, more like brother and sister than mother and son.” [22]

Lady Randolph was well-respected and influential in the highest British social and political circles. She was said to be intelligent, witty, and quick to laughter. It was said that Queen Alexandra especially enjoyed her company, although Lady Randolph had been involved in an affair with her husband the king, which was well known to Alexandra.[23] Through her family contacts and her extramarital romantic relationships, Lady Randolph greatly helped her husband's early career, as well as that of her son Winston.

Later marriages

editLord Randolph died in 1895, aged 45. His death freed Jennie to move on effortlessly despite her lack of money; she mixed in the highest London society circles. Attending a weekend party in July 1898 hosted by Daisy Warwick, Jennie was introduced to George Cornwallis-West, a captain in the Scots Guards who was just 16 days older than her own son Winston; he was instantly smitten, and they spent much time together. George and Jennie were married on 28 July 1900 at St Paul's Church, Knightsbridge.[24]

Around this time, Jennie became well known for chartering the hospital ship Maine[25] to care for those wounded in the Second Boer War. [26] She headed the effort to charter the ship in partnership with two American-born socialites residing in London: Jennie Goodell Blow and Fanny Ronalds.[27][28][29] For this work, Churchill was awarded the decoration of the Royal Red Cross (RRC) in the South Africa Honours list published on 26 June 1902.[26] Churchill received the decoration in person from King Edward VII on 2 October 1902 during a visit to Balmoral Castle.[30]

In 1908, she wrote her memoirs, The Reminiscences of Lady Randolph Churchill.

George doted on Jennie, amorously nicknaming her "pussycat". However, they drifted apart. The Churchills were becoming a dedicated literary family, and George, who was a financial failure in the City, slowly fell out of love with his wife, who was old enough to be his mother. Short of money, Jennie contemplated selling the family home in Hertfordshire to move into the Ritz Hotel in Piccadilly. George was in fragile health, and recuperated at the Swiss skiing resort of St Moritz. Jennie took to writing plays for the West End, in many of which the star was Mrs. Patrick Campbell.

Jennie separated from George in 1912, and they were divorced in April 1914, whereupon Cornwallis-West married Mrs. Campbell. Jennie dropped the surname Cornwallis-West, and resumed, by deed poll, the name Lady Randolph Churchill.[31]

Her third marriage, on 1 June 1918, was to Montagu Phippen Porch (1877–1964), a member of the British Civil Service in Nigeria, who was younger than her son Winston by three years. At the end of World War I, Porch resigned from the colonial service. After Jennie's death, he returned to West Africa, where his business investments had proven successful.[32]

Death

editIn May 1921, while Montagu Porch was away in Africa, Jennie slipped while coming down a friend's staircase wearing new high-heeled shoes, breaking her ankle. Gangrene set in, and her left leg was amputated above the knee on 10 June. At age 67, she died at her home at 8 Westbourne Street in London on 29 June, following a haemorrhage of an artery in her thigh resulting from the amputation.[33][34]

She was buried in the Churchill family plot at St Martin's Church, Bladon, Oxfordshire, next to her first husband.

Cocktail misattribution

editThe invention of the Manhattan cocktail is sometimes erroneously attributed to Jennie Churchill, who supposedly asked a bartender to make a special drink to celebrate the election of Samuel J. Tilden to the New York governorship in 1874. However, though the drink is believed to have been invented by the Manhattan Club (an association of New York Democrats) on that occasion, Jennie could not have been involved as she was in Europe at the time, about to give birth to her son Winston later that month.[35]

Portrayals

edit- Jennie Churchill was portrayed by Anne Bancroft in the film Young Winston (1972) and by Lee Remick in the British television series Jennie: Lady Randolph Churchill (1974).

See also

edit- The Anglo-Saxon Review, a quarterly miscellany edited by Lady Randolph Churchill

Notes

edit- ^ This British person has the barrelled surname Spencer-Churchill, but is known by the surname Churchill.

- ^ Her legal name was Jennie, per the 1874 marriage license bearing witness to her union with Lord Randolph Spencer-Churchill, accessed on ancestry.com on 21 January 2017.

- ^ Brooklyn was an independent city prior to the consolidation of the cities of New York (then Manhattan and the Bronx) and Brooklyn with the largely rural areas of Queens and Staten Island in 1898.

References

edit- ^ "Jennie Jerome Churchill | American Heiress, Winston Churchill's Mother | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- ^ Martin, R.G. (1990). Jennie: The Life of Lady Randolph Churchill. Jennie: The Life of Lady Randolph Churchill. Prentice-Hall. p. 324. ISBN 978-0-13-511882-5. Retrieved 24 July 2024.

The date recorded in the family Bible, although put in some years later, was made by Leonard Jerome's cousin, Margaret Middleton, an historian for the Daughters of the American Revolution and an accomplished genealogist. She unquestionably checked her facts with the immediate family. Further confirmation of the 1854 birth-date comes from a letter Jennie wrote to her husband on January 8, 1883, thanking him for a present: "Just in time for my birthday tomorrow—29 my dear; but I shall not acknowledge it to the world. 26 is quite enough.

- ^ G. H. L. Le May, "Churchill, Jeanette [Lady Randolph Churchill] (1854–1921)", rev. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online ed., May 2006, accessed 18 September 2010

- ^ Lovell, Mary (2011). The Churchills in Love And War. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-393-06230-4.

- ^ Churchill, Randolph S. (1966), Winston S. Churchill: Volume One: Youth, 1874–1900, pp. 15–16

- ^ Ralph G. Martin Jennie: The Life of Lady Randolph Churchill—The Romantic Years, 1854–1895, 9th printing, 1969

- ^ "Churchill Had Iroquois Ancestors". Winstonchurchill.org. 29 June 1921. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- ^ Anne Saba, American Jennie, Norton, 2008, page 13

- ^ "Winston Churchill's Mother Jennie Jerome Was Born in Cobble Hill, But in Which House?". Cobble Hill Association. 15 June 2011. Archived from the original on 30 January 2012. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ Lovell, Mary (2011). The Churchills in Love And War. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-393-06230-4.

- ^ Lovell, Mary S., The Churchills, Little Brown, London, 2011, p. 28.

- ^ Lovell, Mary S., The Churchills, Little Brown, London, 2011, p.259.

- ^ "Work of American Women's War Relief Fund in London". New York Herald. 31 December 1916. Retrieved 26 April 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Two Hospitals for U.S. Troops Wounded". Salisbury Evening Post. 20 June 1917. Retrieved 27 April 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Helping in Britain: The American Women's War Relief Fund". American Women in World War I. 9 January 2017. Archived from the original on 27 September 2017. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ^ Anita Leslie. Jennie: The Life of Lady Randolph Churchill, 1969

- ^ van der Werff, Adriaen; Starling, Thomas; Churchill, John; Churchill, Randolph; Churchill, Winston; Pond, James B.; Purdy, J. E.; Churchill, Jennie Jerome; Churchill, John Spencer (10 July 2004). "An Age of Youth - Churchill and the Great Republic | Exhibitions - Library of Congress". www.loc.gov. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- ^ a b William Manchester, The Last Lion, ISBN 0-440-54681-8

- ^ Johnson, Paul (2010). Churchill. New York, NY: Penguin. p. 4. ISBN 978-0143117995.

- ^ Anne Sebba, American Jennie: The Remarkable Life of Lady Randolph Churchill", Norton, 2008

- ^ Manchester, William, Winston Spencer Churchill, The Last Lion, Laurel, Boston, 1989 edition, p. 137, ISBN 0-440-54681-8.

- ^ Churchill, Winston, My Early Life, 1930, Touchstone, 1996 edition, p.28.

- ^ "Edward VII". Archived from the original on 27 October 2009. Retrieved 18 October 2007.

- ^ MacColl, Gail; Wallace, Carol McD. (2012). To Marry an English Lord: Tales of Wealth and Marriage, Sex and Snobbery. New York: Workman Publishing. p. 364. ISBN 9780761171959. OCLC 883485021.

- ^ "UNITED STATES HOSPITAL SHIP". Trove. 25 January 1900. Retrieved 18 April 2024.

- ^ a b "No. 27448". The London Gazette (Supplement). 26 June 1902. p. 4193.

- ^ Thurmond, Aubri E. (December 2014). "Under Two Flags: Rapprochement and the American Hospital Ship Maine: A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of the Texas Woman's University Department of History and Government College of Arts and Sciences" (PDF). Texas Women's University. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ "Americans Honored". Newspapers.com. Wilkes-Barre Times Leader. 7 August 1901. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ "Mrs. Blow is Enroute Home". Valentine Democrat. 23 May 1901. Retrieved 10 April 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Court Circular". The Times. No. 36889. London. 3 October 1902. p. 7.

- ^ "No. 28820". The London Gazette. 10 April 1914. p. 3130.

- ^ Lovell, Mary S., The Churchills, Little Brown, London, 2011, p.332, ISBN 978-1-4087-0247-5.

- ^ Jenkins, Roy., Churchill, Pan Books, London, 2002 edition, pp.353–354, ISBN 0-330-48805-8.

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- ^ "Jennie and the Manhattan". The New York Times. 23 December 2007. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

Further reading

edit- Churchill, Lady Randolph Spencer. The Reminiscences of Lady Randolph Churchill, 1908 (Autobiography)

- Kraus, René (1943). Young Lady Randolph. Longman's Green & Co.

- Leslie, Anita. Jennie: The Life of Lady Randolph Churchill, 1969

- Martin, Ralph G. Jennie: The Life of Lady Randolph Churchill – The Romantic Years, 1854–1895 (Prentice-Hall, Ninth printing, 1969)

- Martin, Ralph G. Jennie: The Life of Lady Randolph Churchill – Volume II, The Dramatic Years, 1895–1921 (Prentice-Hall, 1971) ISBN 0-13-509760-6

- Martin, Ralph G. Reissue of both volumes of Jennie: The Life of Lady Randolph Churchill, (Sourcebooks, 2007) ISBN 978-1-4022-0972-7

- Sebba, Anne. American Jennie: The Remarkable Life of Lady Randolph Churchill (W.W. Norton, 2007) ISBN 0-393-05772-0