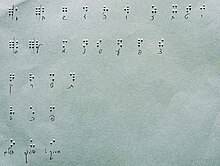

Hebrew Braille (Hebrew: ברייל עברי) is the braille alphabet for Hebrew. The International Hebrew Braille Code is widely used. It was devised in the 1930s and completed in 1944. It is based on international norms, with additional letters devised to accommodate differences between English Braille and the Hebrew alphabet.[1] Unlike Hebrew, but in keeping with other braille alphabets, Hebrew Braille is read from left to right instead of right to left,[2] and unlike English Braille, it is an abjad, with all letters representing consonants.

| Hebrew Braille ברייל עברי | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | |

Print basis | Hebrew alphabet |

| Languages | Hebrew |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | Braille

|

History

editPrior to the 1930s, there were several regional variations of Hebrew Braille, but no universal system.[1] In 1930, the Jewish Braille Institute of America, under the direction of the Synagogue Council of America, assembled an international committee for the purpose of producing a unified embossed code to be used by sightless people throughout the world. The committee membership consisted of Isaac Maletz, representing the Jewish Institute for the Blind, Jerusalem; Dr. Max Geffner, of the Blindeninstitut of Vienna; Canon C. F. Waudby, of the National Institute for the Blind, Great Britain; Leopold Dubov, of the Jewish Braille Institute of America; and Rabbi Harry J. Brevis, representing the New York Board of Rabbis. Rabbi Brevis, who had lost his eyesight in his mid 20s, and who had developed a system of Hebrew braille for his personal use as a rabbinical student while attending the Jewish Institute of Religion from 1926 and 1929, was named chairman of the committee, and Leupold Dubov, the executive director of the Jewish Braille Institute of America, was appointed secretary. In 1933, the committee voted unanimously to approve and sponsor Brevis' system for adoption as the International Hebrew Braille Code. Brevis published a selection of readings from the Bible, Mishnah, and contemporary literature using this system in 1935 under the title A Hebrew Braille Chrestomathy.[3] Among the greater challenges faced by the committee was the accommodation of the Hebrew vowel points. In 1936,[1] the first Hebrew Braille book was published with sponsorship from the Library of Congress: a volume of excerpts from the Talmud and other sources.[4] The code underwent further refinements for the better part of a decade until its completion in 1944.[1]

Basic alphabet

editBecause Hebrew Braille derives from English Braille, there is not a one-to-one match between Hebrew letters in print and in braille. Most obviously, four consonants with the dagesh point in print have distinct letters in braille, but three others require a dagesh prefix ⠘ in braille. The different placements of the dot on the print letter shin also correspond to two different letters in braille. On the other hand, the distinct final forms of some letters in print are not reflected in braille.

In the table below, the braille letters corresponding to basic letters in print are in the top row, while those derived by pointing in print, and which have a distinct pronunciation in Modern Hebrew, are in the second row.

Basic

|

Braille | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| א ’ | ב v | ג g | ד dh | ה h | ו w | ז z | ח ḥ | ט ṭ | י y | כ ך kh | ||

Dagesh

|

Braille | |||||||||||

| בּ b bb |

וּ û ww |

כּ ךּ k kk | ||||||||||

Basic

|

Braille | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ל l | מ ם m | נ ן n | ס s | ע ‘ | פ ף f | צ ץ ts | ק q | ר r | ש שׁ sh | ת th | ||

Dagesh

|

Braille | |||||||||||

| פּ p pp |

שׂ ś [5] |

תּ t tt | ||||||||||

For other pointed print consonants, such as gimel with dagesh גּ, the braille prefix is used: ⠘⠛. Historically, this sequence has two values: a 'hard' gee [ɡ] (cf. plain gimel ⠛ [ɣ]), and a double/long gee [ɡː]. However, it is not distinct in Modern Hebrew. It is not clear if the prefix can be added to letters that have partners in the bottom row of the table above to distinguish, say, dagesh hazak kk from dagesh kal k, or ww from û.

When transcribing completely unpointed print texts, only the top row of braille letters is used.

Vowel pointing

editApart from those written with ו and י and thus obligatory in print, vowels are optional in braille just as they are in print. When they are written, braille vowels are full letters rather than diacritics.

| Braille | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ◌ִ i | ◌ֵ e | ◌ֶ ẹ | ◌ַ a | ◌ָ ọ | ◌ֹ o | ◌ֻ u | ||

| Braille | ||||||||

| ◌ְ ə | יִ î | יֵ ê | ◌ֱ ĕ | ◌ֲ ă | ◌ֳ ŏ | וֹ ô | וּ û |

Print digraphs with אְ schwa (אֱ ĕ, אֲ ă, אֳ ŏ, bottom row), and the matres lectionis (וּ û, וֹ ô, יִ î) are derived in braille by modifying (lowering or reflecting) the base vowel. יֵ ê does not have a dedicated braille letter, and is written as the vowel ⠌ e plus ⠚ yod.

Numbers

edit| Braille | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 0 |

Punctuation

editThe punctuation used with Hebrew Braille, according to UNESCO (2013), is as follows:

| , |

’ |

; |

: |

. |

! |

? “ |

" |

– |

/ |

* | |

| ... ( ... ) |

... [ ... ] |

— |

... | ||||||||

Jewish Heritage for the Blind

editJewish Heritage for the Blind, although organizationally unrelated to Jewish Braille Institute,[6] has a related mission: to provide Braille[7] and Large Print texts,[8] in particular for religious services.[9]

References

edit- ^ a b c d Okin, Tessie (August 15, 1952). "I Shall Light a Candle". Canadian Jewish Chronicle. Retrieved October 19, 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Mackenzie, Clutha Nantes; Sir Clutha Nantes Mackenzie (1954). World Braille Usage: a survey of efforts towards uniformity of braille notation. UNESCO.

- ^ Brevis, Harry (1969). "The Story of Hebrew Braille" (PDF). americanjewisharchives.org/publications/journal/PDF/1969_21_02_00.pdf.

- ^ Blumenthal, Walter Hart (1969). Bookmen's Bedlam: an Olio of Literary Oddities. Ayer Publishing. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-8369-1022-3.

- ^ Placed here for convenience only; not actually a letter with dagesh

- ^ "Paid Notice: Deaths GALLARD, ROSALIND". The New York Times. July 27, 1998. Retrieved September 28, 2022.

- ^ Jeane MacIntosh (January 21, 2008). "Real Bum $teers". The New York Post. Retrieved September 28, 2022.

- ^ Jeane MacIntosh (December 1, 2008). "Dollars to Donuts". New York Post. Retrieved September 28, 2022.

- ^ Constance L. Hays (October 21, 1998). "Getting Rid of That Heap, While Saving a Heap of Trouble". The New York Times. Retrieved September 28, 2022.

- UNESCO (2013) World Braille Usage, 3rd edition.