Bringing Up Father is an American comic strip created by cartoonist George McManus. Distributed by King Features Syndicate, it ran for 87 years, from January 2, 1913, to May 28, 2000.

| Bringing Up Father | |

|---|---|

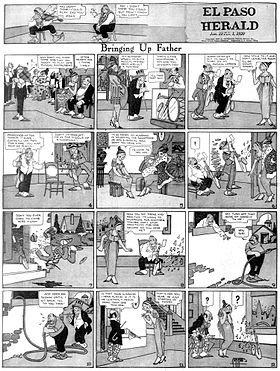

Bringing Up Father (January 31, 1920) | |

| Author(s) | George McManus |

| Current status/schedule | Concluded |

| Launch date | January 2, 1913 |

| End date | May 28, 2000 |

| Alternate name(s) | Maggie & Jiggs |

| Syndicate(s) | King Features Syndicate |

| Genre(s) | Humor |

The strip was later titled Jiggs and Maggie (or Maggie and Jiggs), after its two main characters. According to McManus, he introduced these same characters in other strips as early as November 1911.[1]

Characters and story

editThe strip centers on an immigrant Irishman named Jiggs, a former hod carrier who came into wealth in the United States by winning a million dollars in a sweepstakes.[2] Now nouveau-riche, he still longs to revert to his former working class habits and lifestyle. His constant attempts to sneak out with his old gang of boisterous, rough-edged pals, eat corned beef and cabbage (known regionally as "Jiggs dinner"), and hang out at the local tavern were often thwarted by Maggie, his formidable, social-climbing (and rolling-pin wielding) harridan of a wife, their lovely young daughter Nora, and infrequently their lazy son Ethelbert, later known as Sonny. Also a character presented in the strip (portrayed as a miserly borrower) was named, fittingly, Titus Canby ("tight as can be").

The strip deals with "lace-curtain Irish", with Maggie as the middle-class Irish American desiring assimilation into mainstream society in counterpoint to an older, more raffish "shanty Irish" sensibility represented by Jiggs. Her lofty goal—frustrated in nearly every strip—is to bring Father (the lowbrow Jiggs) "up" to upper class standards, hence the title, Bringing Up Father. The occasional malapropisms and left-footed social blunders of these upward mobiles were gleefully lampooned in vaudeville and popular song, and formed the basis for Bringing Up Father.[3]

Varied interpretations of McManus's work often highlight difficult issues of ethnicity and class, such as the conflicts over assimilation and social mobility that second- and third-generation immigrants confronted. McManus took a middle position, which aided ethnic readers in becoming accepted in American society without losing their identity.[4] A cross-country tour that the characters took in September 1939 into 1940 gave the strip a big promotional boost and raised its profile in the cities they visited.[5]

Jiggs and Maggie were generally drawn with circles for eyes, a feature also associated with the later strip Little Orphan Annie.

Origin and sources

editMcManus, who numbered Aubrey Beardsley among his influences, had a bold, clean-cut cartooning line. His strong sense of composition and Art Nouveau and Art Deco design made the strip a stand-out on the comics page.

McManus was inspired by The Rising Generation, a musical comedy by William Gill that he had seen as a boy in St. Louis, Missouri's Grand Opera House, where his father was manager. In The Rising Generation, Irish-American bricklayer Martin McShayne (played by the fat Irish comedian Billy Barry in the stage production McManus saw) becomes a wealthy contractor, yet his society-minded wife and daughter were ashamed of him and his lowbrow buddies, prompting McShayne to sneak out to join his pals for poker. McManus knew Barry and used him as the basis for his drawings of Jiggs. McManus's wife, the former Florence Bergere, was the model for daughter Nora.

One of McManus's friends, restaurateur James Moore, claimed he was the inspiration for the character Dinty Moore, the owner of Jiggs's favorite tavern. James Moore changed his name to Dinty and founded a real-life restaurant chain. The restaurant owner, however, did not begin the successful line of Dinty Moore canned goods marketed today by Hormel.

A surrealistic running gag throughout the strip, always removed from the main action of the story, involved hanging wall paintings that "come to life", with subjects often "breaking the fourth wall", escaping the confines of the picture frames, or changing position from panel to panel within the same strip. None of the nominal stars of the strip ever seemed to notice the animated figures, or anything unusual happening on the walls in the background directly behind them.

Comics historian Don Markstein wrote about McManus's characters:

- On January 12, 1913 [actually January 2], he debuted Bringing Up Father, about an Irishman named Jiggs, who doesn't understand why his ascension to wealth via the Irish Sweepstakes means he can't hang out with his friends, and his nagging, social-climbing wife, Maggie. The strip was an instant hit, possibly because of its combination of an appealing cast of characters with a unique look of art-nouveau splendor... Before McManus died, in 1954, Bringing Up Father made him two fortunes (the first was lost in the 1929 stock market crash). By that time, Jiggs's Irishness had faded—the new generation saw him as just a rich guy that liked to hang out with a regular crowd.[6]

An uncredited script collaborator on the strip was McManus's brother, Charles W. McManus, who was 61 when he died August 31, 1941. He also had his own comic strips in the 1920s, Dorothy Darnit and Mr. Broad.[7]

Topper strips

editIn 1926, McManus added a Sunday topper strip above Bringing Up Father, beginning with No Brains But (January 10 to May 9, 1926) and Good Morning, Boss! (May 16 to June 6, 1926). Starting on June 13, 1926, McManus changed the topper to Rosie's Beau, a revival of his previous Sunday page (which ran from October 29, 1916 to April 7, 1918). Rosie's Beau continued as the topper until November 12, 1944.[8]

On April 17, 1938, an absent-minded character named Sir Von Platter in Rosie's Beau realized he was in the wrong place and climbed down into the first panel of Bringing Up Father, arriving in the living room of Maggie and Jiggs.[9]

Starting on November 19, 1944, McManus replaced Rosie's Beau with Snookums, itself a revival of a 1904-1916 McManus strip, The Newlyweds and Their Baby, now focused on their son, the titular character. Snookums remained as the topper for Bringing Up Father until December 31, 1956, at which point it became a standalone Sunday feature distributed until the early 1960s.[10]

In the final episode of HBO's The Pacific (2010), Robert Leckie (James Badge Dale) is seen reading Snookums.

Other minor topper panels overlapping with the above were Things We Can Do Without (July 23, 1933 to April 22, 1934), How to Keep From Getting Old (April 1, 1934 to May 19, 1935), It's the Gypsy in Me (May 26, 1935 to April 25, 1937) and What'll I Do Now (January 5 to March 15, 1936).[11]

Artists

editBetween 1935 and 1954, McManus's assistant Zeke Zekley made a major contribution to the strip in both writing and art. Other artists, including Bill Kavanagh and Frank Fletcher, also contributed. When McManus died in 1954, King Features replaced Zekley with Vernon Greene. With Greene's death in 1965, Hal Campagna stepped in, and Frank Johnson (Boner's Ark) replaced Campagna in 1980. Hy Eisman ghosted the strip for a short time after Greene's death. King Features wanted him to take it over, but Eisman was close friends with Greene, and he was unable to agree to take the strip on.[12] The strip's popularity faded, and Bringing Up Father limped along until its 87-year run came to a close on May 28, 2000.

In 1995, the strip was one of 20 included in the Comic Strip Classics series of commemorative US postage stamps. Bringing Up Father went digital in 2007 when King Features made the strip available as one of the selections in its DailyINK email package.

International syndication

editIn Mexico, the strip was titled Educando a Papá, with Jiggs and Maggie being renamed as "Pancho" and "Ramona" respectively. In Chile, Jiggs was known as "Don Fausto". In Argentina, it was known as Trifón y Sisebuta, and in Brazil as Pafúncio e Marocas.[13] In Yugoslavia and Serbia it has been published as Porodica Tarana since 1935. In Turkey, the strip was published daily by Hürriyet until the late 1990s under the name Güngörmüşler (The Worldly-wiseds) with Jiggs renamed to Şaban and Maggie renamed to Tonton (darling). In Italy, Jiggs and Maggie became Arcibaldo e Petronilla and the strip, published by the children magazine Corriere dei Piccoli since 1921, was very popular.

Bringing Up Father still enjoys popularity in Norway. Known as Fiinbeck og Fia, the strip was published weekly in the family journal Hjemmet from 1921 until the early 2000s; and a Christmas book with the strip has been published every year since 1930, in the last few decades mostly reprints of material produced by McManus in the 1940s and 1950s. A similar publication was also an annual event (from 1931 to 1977) in Sweden, where the strip is known as Gyllenbom. In Denmark the series went under the name Gyldenspjæt. In Finland, the strip was called Vihtori ja Klaara and appeared in the major daily Uusi Suomi from 1929 until the paper folded in 1991. In the Finnish version, Jiggs' favorite dish of corned beef and cabbage became lammaskaali (literally "mutton cabbage"), which under the name fårikål is actually a Norwegian national dish.

In Japan, Bringing Up Father was first published in April 1st, 1923 in the Asahi Graph, as Oyaji kyōiku.[14][15] The strip was published daily in the magazine (interrupted by the Great Kantō earthquake, resuming to be published weekly from November 14 afterwards) until 1940; its success inspired strips by Japanese comic artists, like Yutaka Asō's Nonkina tōsan ("Easygoing daddy").[14]

Maggie and Jiggs in other media

editStage

editGus Hill's production of Bringing Up Father opened on Broadway in 1914, with music composed by Frank H. Grey, lyrics by Elven E. Hedges, libretto by John P. Mulgrew and Thomas Swift, choreography by Edward Hutchinson, and directed by Frank Tannehill, Jr. Hill produced many more theatrical versions of the strip that toured the country, including Bringing Up Father in Florida, Bringing Up Father on Broadway, Bringing Up Father in Ireland, Bringing Up Father Abroad, and Bringing Up Father in Wall Street.

Bringing Up Father at the Seashore opened on Broadway at the Manhattan Opera House in 1921, but closed after 18 performances; a revised version reopened in 1928. Another of Hill's productions of Father opened at the Lyric Theatre in 1925. According to The Holloway Pages' history of the strip: "Reportedly, this version had Maggie following a fleeing Jiggs from Ireland to a yacht headed for Spain, but the story was halted frequently for various vaudeville acts. The show closed after 24 performances".[16]

Sheet music

edit- "By the Susquehanna Shore" (from Bringing Up Father, 1914)

- Bringing Up Father on Broadway (1919) - songs include: "The Lotus Club Rag", "Dry Those Tears", ""The Fair Irene, and "All for a Girl"

- "I'm Longing for a Pair of Irish Eyes" (from Bringing Up Father in Florida, 1920)

- Bringing Up Father (1920 green cover, same design as earlier red cover) - songs include: "The Rose You gave me", "Why Don't They Let the Girlies go to Sea?", and "Let's Get the Irish over Here". PLUS: advice, jokes and magic tricks.

- Bringing Up Father in Wall Street (1921) - songs include: "Rose of My Heart", "Somebody's Darling Boy", "When That Mobile Boy Sings the Memphis Blues", "The Wonderful Way You Love", "I'm Free, Single, Disengaged", "Looking for Someone to Love", "There's No Fool Like an Old Fool", "My Dixie Rose", "Million Dollar Smile", and Just One Little Smile"

- Bringing Up Father Song Book (1922) - songs include: "Sweet Southern Lullaby", "Dear Old-Fashioned Mother", and "China Doll"

- "They'll Never Bring Up Father 'Till They Tear Down Dinty Moore's" (1923)

Radio

edit

Sponsored by Lever Brothers, the Bringing Up Father radio series aired on the Blue Network from July 1 to September 30, 1941, starring Mark Smith (1887–1944) as Jiggs and Agnes Moorehead as Maggie. Neil O'Malley also portrayed Jiggs. Their daughter Nora was played by Helen Shields and Joan Banks. Craig McDonnell (1907–1956) was heard in the role of Dinty Moore. The 30-minute program aired Tuesdays at 9pm.[17]

Animation

editThe following are silent animated cartoons based on Bringing Up Father, all produced by International Film Service and released through Pathé Exchange:[18]

- Father Gets into the Movies (1916)

- Just Like a Woman (1916)

- A Hot Time in the Gym (1917)

- The Great Hansom Cab Mystery (1917)

- Music Hath Charms (1917)

- He Tries His Hand at Hypnotism (1917)

- The Stimulating Mrs. Barton (1918)

- Father's Close Shave (1918)

- Jiggs and the Social Lion (1918)

In 1924, a Chilean studio created a feature-length film entitled Vida y milagros de Don Fausto ("Life and Miracles of Jiggs"), which used the strip's characters (likely without authorization). This is the second oldest-known animated film made in the country.

In 1927, Norwegian filmmaker Ottar Gladtvet produced one of the country's earliest animated films, a commercial featuring Jiggs and Maggie titled Fiinbeck er rømt ("Jiggs Has Run Away"), in which Maggie purchases the finest tobacco Tiedemanns Tobakk AS has to offer in a bid to keep Jiggs from going out.[19]

Live-action two-reel shorts

editA series of live-action silent comedies featured comedian Johnny Ray as Jiggs, Margaret Cullington as Maggie and Laura La Plante as daughter Nora. Directed by Reggie Morris, these were produced by International Film Service and released through Pathé Exchange. Confusingly enough, a couple of the titles were duplicated from the earlier cartoons. This series included:

- Jiggs in Society (1920)

- Jiggs and the Social Lion (1920)

- Jiggs' Close Shave [aka Father's Close Shave] (1920)

Live-action feature films

editThe following feature-length films were based on the strip:

- Bringing Up Father (1928) Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer: Silent comedy directed by Jack Conway, written by Frances Marion with titles by Ralph Spence, starring J. Farrell MacDonald as Jiggs, Polly Moran as Maggie, Gertrude Omstead as their daughter (renamed "Ellen"), and Jules Cowles and Marie Dressler as Mr. and Mrs. Dinty Moore.

- Vihtori ja Klaara (Finland, 1939): The first sound comedy based on the strip, although the characters are speaking Finnish; directed by filmmaker Teuvo Tulio.

The Jiggs and Maggie film series, all released by Monogram Pictures:

- Bringing Up Father (1946) directed by Edward F. Cline and written by Cline, Barney Gerard and Jerry Warner, starring Joe Yule as Jiggs, Renie Riano as Maggie, George McManus (as himself), Tim Ryan as the stingy and belligerent Dinty Moore, and Pat Goldin as the ever-silent Dugan.

- Jiggs and Maggie in Society (1948)

- Jiggs and Maggie in Court (1948)

- Jiggs and Maggie in Jackpot Jitters (1949)

- Jiggs and Maggie Out West (1950)

The series was discontinued due to the death of Joe Yule in March 1950. Yule is the father of Mickey Rooney, who expressed interest in reviving Jiggs onstage in the late 1980s. Both Martha Raye and Cloris Leachman were considered for the part of Maggie, but the project was never produced.

Comic books

edit- Bringing Up Father was a feature of David McKay's King Comics title from No. 60 to No. 135 (1941–1947).

- Jiggs and Maggie Standard Comics (11 issues, 1949–1953)

- Jiggs and Maggie Harvey Comics (6 issues, 1953–1954)

Collections and reprints

edit- 1919–1934: Cupples & Leon produced 26 semi-annual daily strip reprints in softcover books measuring 10" x 10". They also published two larger, hardcover editions; Bringing Up Father: The BIG Book in 1926 and Bringing Up Father: BIG Book No. 2 in 1929.

- Whitman Publishing released Bringing Up Father: A Big Little Book in 1936.

- Charles Scribner's Sons published a hardcover anthology, Bringing Up Father: Starring Maggie and Jiggs in 1973. ISBN 0-517-16724-7

- Hyperion Press released the reprint volume Bringing Up Father: A Complete Compilation, 1913-1914 in their "Hyperion Library of Classic American Comic Strips" series in 1977, available in both hardcover and paperback editions.

- In 1986 The Celtic Book Company released Jiggs Is Back, a full-color, 64-page oversized trade paperback of Sunday strip reprints. ISBN 0-913666-82-3

- NBM reprinted the first two years of the daily strip in July 2009 as part of their "Forever Nuts" series: Forever Nuts Presents: Bringing Up Father. ISBN 1-56163-556-1

- In November 2009 IDW Publishing's The Library of American Comics imprint reprinted the cross-country tour storyline that ran from January 1939 to July 1940 as Bringing Up Father: From Sea to Shining Sea ISBN 1-60010-508-4, followed by Bringing Up Father: Of Cabbages and Kings, IDW Publishing's The Library of American Comics. ISBN 978-1-61377-532-5

Parodies and guest appearances

edit- In issue #17 of Mad, Harvey Kurtzman's story "Bringing Back Father", illustrated by Will Elder and Bernard Krigstein, depicted Jiggs as the victim of domestic abuse, bruised and bleeding after physical assaults by the domineering Maggie, who has struck Jiggs with thrown kitchen utensils and crockery.[20] When Kurtzman died in 1993, slides from this parody were shown by Art Spiegelman at Kurtzman's memorial service in the Time-Warner building.

- In his book In the Shadow of No Towers, Spiegelman drew himself as Jiggs and his wife as Maggie. He also included a reprint of a Bringing Up Father Sunday strip.[21]

- In the comic strip Arlo and Janis (March 17, 2006), Jiggs is invited to the home of Arlo and Janis for corned beef and cabbage in honor of the day. He enjoys himself immensely, and entertains his hosts with his stories, jokes and witticisms. Everyone has a happy St. Patrick's Day.

- In Marvel Comics' Power Pack, Jiggs is the King of Elsewhere and receives a visit from Katie Power. Maggie is the Queen, wiser and more powerful than the King.[22]

- Jiggs and Maggie renew their friendship with Walt Wallet in Gasoline Alley, by Jim Scancarelli, on April 30, 2013. This continues on August 10, 2018.

References

edit- ^ Goulart, Ron, editor. The Encyclopedia of American Comics. Facts on File, 1990.

- ^ Merwin, Ted. "In Their Own Image", Rutgers, 2006.

- ^ William H. A. Williams, "Green Again: Irish-American Lace-Curtain Satire", New Hibernia Review, Winter 2002, Vol. 6 Issue 2, pp 9–24

- ^ Kerry Soper, "Performing 'Jiggs': Irish Caricature and Comedic Ambivalence Toward Assimilation and the American Dream in George Mcmanus's 'Bringing Up Father'", Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, April 2005, Vol. 4#2, pp 173–213.

- ^ ""Big Deals: Comics' Highest-Profile Moments", Hogan's Alley #7, 1999". Archived from the original on June 30, 2013. Retrieved November 21, 2012.

- ^ Bringing Up Father at Don Markstein's Toonopedia. Archived from the original on February 12, 2016.

- ^ "Brother of George—Idea Man for 'Bringing Up Father' Cartoon". The New York Times, September 1, 1941.

- ^ Holtz, Allan (2012). American Newspaper Comics: An Encyclopedic Reference Guide. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. pp. 85, 174, 288, 335. ISBN 9780472117567.

- ^ Inge, M. Thomas. Anything Can Happen in a Comic Strip: Centennial Reflections on an American Art Form. University of Mississippi Press, 1995.

- ^ Holtz, Allan (2012). American Newspaper Comics: An Encyclopedic Reference Guide. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. pp. 286, 358. ISBN 9780472117567.

- ^ Holtz, Allan (2012). American Newspaper Comics: An Encyclopedic Reference Guide. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. pp. 197, 209, 383, 408. ISBN 9780472117567.

- ^ "A Profile of Hy Eisman, Hogan's Alley #15". Archived from the original on November 12, 2014. Retrieved November 17, 2014.

- ^ "Pafúncio e George McManus - História!". February 14, 2010. Archived from the original on February 14, 2010. Retrieved June 5, 2023.

- ^ a b Woo, Benjamin; Stoll, Jeremy (July 29, 2021). The Comics World: Comic Books, Graphic Novels, and Their Publics. Univ. Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-4968-3468-3.

- ^ Exner, Eike (November 12, 2021). Comics and the Origins of Manga: A Revisionist History. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-1-9788-2723-3.

- ^ The Holloway Pages: Bringing Up Father page

- ^ Dunning, John (1998). On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio (Revised ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-19-507678-3. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. p. 23. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- ^ https://filmarkivet.no/film/details.aspx?filmid=400449 Fiinbeck er rømt

- ^ Mad 17

- ^ Spiegelman, Art. In the Shadow of No Towers.

- ^ Marvel, Power Pack, Volume 1, #47, July 1989. Script by Jon Bogdanove.

Sources

edit- Strickler, Dave. Syndicated Comic Strips and Artists, 1924–1995: The Complete Index. Cambria, California: Comics Access, 1995. ISBN 0-9700077-0-1