Johann Baptist Strauss II (German: [ˈjoːhan bapˈtɪst ˈʃtʁaʊs]; 25 October 1825 – 3 June 1899), also known as Johann Strauss Jr., the Younger or the Son (German: Johann Strauß Sohn), was an Austrian composer of light music, particularly dance music and operettas as well as a violinist. He composed over 500 waltzes, polkas, quadrilles, and other types of dance music, as well as several operettas and a ballet. In his lifetime, he was known as "The Waltz King", and was largely responsible for the popularity of the waltz in Vienna during the 19th century. Some of Johann Strauss's most famous works include "The Blue Danube", "Kaiser-Walzer" (Emperor Waltz), "Tales from the Vienna Woods", "Frühlingsstimmen", and the "Tritsch-Tratsch-Polka". Among his operettas, Die Fledermaus and Der Zigeunerbaron are the best known.

Johann Strauss II | |

|---|---|

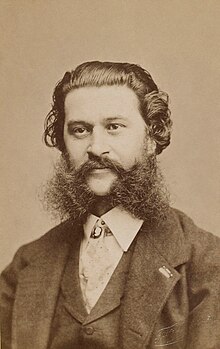

Strauss in 1876 | |

| Born | 25 October 1825 Vienna, Austrian Empire |

| Died | 3 June 1899 (aged 73) Vienna, Austria-Hungary |

| Resting place | Vienna Central Cemetery |

| Occupation | Composer |

| Spouses | Angelika Dittrich

(m. 1878; div. 1882)Adele Deutsch (m. 1887) |

| Father | Johann Strauss I |

| Relatives |

|

| Signature | |

Strauss was the son of Johann Strauss I and his first wife Maria Anna Streim. Two younger brothers, Josef and Eduard Strauss, also became composers of light music, although they were never as well known as their brother.

Spelling of name

editAlthough the name Strauss can be found in reference books frequently with "ß" (Strauß), Strauss himself wrote his name with a long "s" and a round "s" (Strauſs), which was a replacement form for the Fraktur-ß used in antique manuscripts. His family called him "Schani" (Johnny), derived from the French "Jean" with addition of the endearment ending "-i".[1]

Early life

editStrauss was born into a Catholic family in St Ulrich near Vienna (now a part of Neubau), Austria, on 25 October 1825, to the composer Johann Strauss I and his first wife, Maria Anna Streim. His paternal great-grandfather was a Hungarian Jew – a fact which the Nazis, who lionised Strauss's music as "so German", later tried to conceal.[2] His father did not want him to become a musician but rather a banker.[3] Nevertheless, Strauss Jr. studied the violin secretly as a child with the first violinist of his father's orchestra, Franz Amon.[3] When his father discovered his son secretly practising on a violin one day, he gave him a severe whipping, saying that he was going to beat the music out of the boy.[4] It seems that rather than trying to avoid a Strauss rivalry, the elder Strauss only wanted his son to escape the rigours of a musician's life.[5] It was only when the father abandoned his family for a mistress, Emilie Trampusch, that the son was able to concentrate fully on a career as a composer with the support of his mother.[6]

Strauss studied counterpoint and harmony with theorist Professor Joachim Hoffmann,[3] who owned a private music school. His talents were also recognized by composer Joseph Drechsler, who taught him exercises in harmony. It was during that time that he composed his only sacred work, the gradual Tu qui regis totum orbem (1844). His other violin teacher, Anton Kollmann, who was the ballet répétiteur of the Vienna Court Opera, also wrote excellent testimonials for him. Armed with these, he approached the Viennese authorities to apply for a license to perform.[7] He initially formed his small orchestra where he recruited his members at the Zur Stadt Belgrad tavern, where musicians seeking work could be hired easily.[8]

Debut as a composer

editJohann Strauss I's influence over the local entertainment establishments meant that many of them were wary of offering the younger Strauss a contract for fear of angering the father.[6] Strauss Jr. was able to persuade Dommayer's Casino in Hietzing, a suburb of Vienna, to allow him to perform.[9] The elder Strauss, in anger at his son's disobedience, and at that of the proprietor, refused to ever play again at Dommayer's Casino,[10] which had been the site of many of his earlier triumphs.

Strauss made his debut at Dommayer's in October 1844, where he performed some of his first works, such as the waltzes "Sinngedichte", Op. 1 and "Gunstwerber", Op. 4 and the polka "Herzenslust", Op. 3.[3] Critics and the press were unanimous in their praise of Strauss's music. A critic for Der Wanderer commented that "Strauss's name will be worthily continued in his son; children and children's children can look forward to the future, and three-quarter time will find a strong footing in him."[3]

Despite the initial fanfare, Strauss found his early years as a composer difficult, but he soon won over audiences after accepting commissions to perform away from home. The first major appointment for the young composer was his award of the honorary position of "Kapellmeister of the 2nd Vienna Citizen's Regiment", which had been left vacant following Joseph Lanner's death two years before.[11]

Vienna was wracked by the revolutions of 1848 in the Austrian Empire, and the intense rivalry between father and son became much more apparent. The son decided to side with the revolutionaries. It was a decision that was professionally disadvantageous, as the Austrian royalty twice denied him the much coveted position of KK Hofballmusikdirektor, which was first designated especially for Johann I in recognition of his musical contributions. Further, the younger Strauss was also arrested by the Viennese authorities for publicly playing "La Marseillaise", but was later acquitted.[12] The elder Strauss remained loyal to the monarchy and composed his "Radetzky March", Op. 228 (dedicated to the Habsburg field marshal Joseph Radetzky von Radetz), which would become one of his best-known compositions.[13]

When the elder Strauss died from scarlet fever in Vienna in 1849, the younger Strauss merged both their orchestras and engaged in further tours.[3] Later, he also composed a number of patriotic marches dedicated to the Habsburg Emperor Franz Josef I, such as the "Kaiser Franz-Josef Marsch" Op. 67 and the "Kaiser Franz Josef Rettungs Jubel-Marsch" Op. 126, probably to ingratiate himself in the eyes of the new monarch, who had ascended the Austrian throne after the 1848 revolution.[3]

Career advancements

editStrauss Jr. eventually attained greater fame than his father and became one of the most popular waltz composers of the era, extensively touring Austria, Poland and Germany with his orchestra. He applied for the position of KK Hofballmusikdirektor (Music Director of the Royal Court Balls), which he finally attained in 1863,[3] after being denied several times before for his frequent brushes with the local authorities.

In 1853, due to constant mental and physical demands, Strauss suffered a nervous breakdown.[3] He took a seven-week vacation in the countryside in the summer of that year on the advice of doctors. Johann's younger brother Josef was persuaded by his family to abandon his career as an engineer and take command of Johann's orchestra in the interim.[3]

In 1855, Strauss accepted commissions from the management of the Tsarskoye-Selo Railway Company of Saint Petersburg to play in Russia for the Vauxhall Pavilion at Pavlovsk in 1856. He would return to perform in Russia every year until 1865.[3]

In 1862, the 27-year-old Eduard Strauss officially joined the Strauss orchestra as another conductor, and he and his brother Josef would lead it until 1870.[14]

Strauss came to the United States in 1872, where he took part in the World's Peace Jubilee and International Musical Festival in Boston at the invitation of bandmaster Patrick Gilmore and was the lead conductor in a "Monster Concert" of over 1000 performers [15] performing his "Blue Danube" waltz. He also conducted other pieces of his at the Festival with a smaller orchestra to great acclaim.[15]

As was customary at the time, requests for personal mementos from celebrities were often in the form of a lock of hair. In the case of Strauss during his visit to America, his valet obliged by clipping Strauss's black Newfoundland dog and providing "authentic Strauss hair" to adoring female fans. However, on account of the high volume of demand, there grew a fear that the dog would be trimmed bald.[16][17][18][19]

Marriages

editStrauss married the singer Henrietta Treffz in 1862, and they remained together until her death in 1878.[3] Six weeks after her death,[3][20] Strauss married the actress Angelika Dittrich. Dittrich was not a fervent supporter of his music, and their differences in status and opinion, and especially her indiscretion, led him to seek a divorce.[3]

Strauss was not granted a decree of annulment by the Roman Catholic Church, and therefore changed religion and nationality, and became a citizen of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha in January 1887.[3] Strauss sought solace in his third wife Adele Deutsch, whom he married in August 1887. She encouraged his creative talent to flow once more in his later years, resulting in many famous compositions, such as the operettas Der Zigeunerbaron and Waldmeister and the waltzes "Kaiser-Walzer" Op. 437, "Kaiser Jubiläum" Op. 434, and "Klug Gretelein" Op. 462.

Musical rivals and admirers

editAlthough Strauss was the most sought-after composer of dance music in the latter half of the 19th century, Carl Michael Ziehrer and Émile Waldteufel provided stiff competition; the latter held a commanding position in Paris.[21] Also, Philipp Fahrbach denied the younger Strauss the commanding position of the KK Hofballmusikdirektor when the latter first applied for the post. The German operetta composer Jacques Offenbach, who made his name in Paris, also posed a challenge to Strauss in the operetta field.[22]

Strauss was admired by other prominent composers: Richard Wagner once admitted that he liked the waltz "Wein, Weib und Gesang" (Wine, Women and Song) Op. 333.[23] Richard Strauss (unrelated), when writing his Rosenkavalier waltzes, said in reference to Johann Strauss, "How could I forget the laughing genius of Vienna?"[24]

Johannes Brahms was a personal friend of Strauss; the latter dedicated his waltz "Seid umschlungen, Millionen!" ("Be Embraced, You Millions!"), Op. 443, to him.[25] A story is told in biographies of both men that Strauss's wife Adele approached Brahms with a customary request that he autograph her fan. It was usual for the composer to inscribe a few measures of his best-known music, and then sign his name. Brahms, however, inscribed a few measures from the "Blue Danube", and then wrote beneath it: "Unfortunately, NOT by Johannes Brahms."[26]

Stage works

editThe most famous of Strauss's operettas are Die Fledermaus, Eine Nacht in Venedig, and Der Zigeunerbaron. There are many dance pieces drawn from themes of his operettas, such as "Cagliostro-Walzer" Op. 370 (from Cagliostro in Wien), "O Schöner Mai" Walzer Op. 375 (from Prinz Methusalem), "Rosen aus dem Süden" Walzer Op. 388 (from Das Spitzentuch der Königin), and "Kuss-Walzer" op. 400 (from Der lustige Krieg), that have survived obscurity and become well-known. Strauss also wrote an opera, Ritter Pázmán,[27] and was in the middle of composing a ballet, Aschenbrödel, when he died in 1899.[28]

Death and legacy

editStrauss often suffered from a variety of lifelong health problems, including hypochondria, several phobias, and bronchial catarrh. In late May of 1899, he developed a respiratory illness which developed into pleuropneumonia, and on 3 June 1899 he died in Vienna, at the age of 73. He was buried in the Zentralfriedhof. At the time of his death, he was still composing his ballet Aschenbrödel.[28]

As a result of the efforts by Clemens Krauss, who performed a special all-Strauss programme in 1929 with the Vienna Philharmonic, Strauss's music is now regularly performed at the annual Vienna New Year's Concert. Distinguished Strauss interpreters include Willi Boskovsky,[29] who carried on the Vorgeiger tradition of conducting with violin in hand, as was the Strauss family custom, as well as Herbert von Karajan, Carlos Kleiber, Lorin Maazel, Zubin Mehta and Riccardo Muti. In addition, the Wiener Johann Strauss Orchester, which was formed in 1966, pays tribute to the touring orchestras which once made the Strauss family so famous.[30] In 1987 Dutch violinist and conductor André Rieu also created a Johann Strauss Orchestra.

Eduard Strauss surprisingly wound up the Strauss Orchestra on 13 February 1901 after concerts in 840 cities around the globe, and pawned the instruments. The orchestra's last violins were destroyed in the firestorm of the Second World War.[31]

Most of the Strauss works that are performed today may once have existed in a slightly different form, as Eduard Strauss destroyed much of the original Strauss orchestral archives in a furnace factory in Vienna's Mariahilf district in 1907.[32] Eduard, then the only surviving brother of the three, took this drastic precaution after agreeing to a pact between himself and brother Josef that whoever outlived the other was to destroy their works. The measure was intended to prevent the Strauss family's works from being claimed by another composer. This may also have been fueled by Strauss's rivalry with another of Vienna's popular waltz and march composers, Carl Michael Ziehrer.[33]

Two museums in Vienna are dedicated to Johann Strauss II. His residence in the Praterstrasse, where he lived in the 1860s, is now part of the Vienna Museum. The Strauss Museum is about the whole family, with a focus on Johann Strauss II.

Portrayals in the media

editThe lives of the Strauss dynasty members are the subject of several film and television features, such as The Great Waltz (1938), remade in 1972; The Strauss Family (1972); The Strauss Dynasty (1991) and Strauss, the King of 3/4 Time (1995). Many other films used his works and melodies. Alfred Hitchcock made a biographical film of Strauss in 1934 called Waltzes from Vienna.

After a trip to Vienna, Walt Disney was inspired to create four feature films. One of those was The Waltz King, a loosely adapted biopic of Strauss, which aired as part of The Wonderful World of Disney in the U.S. in 1963.[34]

Works

editReferences

editCitations

edit- ^ "Eymology of the word Schani". educalingo.

- ^ "The story of the forgery in 1941 of the entry for the marriage of Johann Michael Strauss to Rosalia Buschin". Wiener Institut für Strauss-Forschung [Vienna Institute for Strauss Research]. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Peter Kemp (2001). "Strauss family". Grove Music Online. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.52380. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0.[full citation needed]

- ^ Fantel 1972, p. 75.

- ^ Gartenberg 1974, p. 124

- ^ a b Gartenberg 1974, p. 121

- ^ Gartenberg 1974, p. 126

- ^ Fantel 1972, p. 76.

- ^ Jacob 1940, p. 127.

- ^ Gartenberg 1974, p. 125

- ^ "Alabama Symphony". Archived from the original on 2 August 2009.

- ^ Fantel 1972, p. 96.

- ^ Fantel 1972, p. 89.

- ^ Weitlaner 2019, p. 56.

- ^ a b Gartenberg 1974, p. 246

- ^ Mark Knowles (2009). The Wicked Waltz and Other Scandalous Dances. McFarland. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-7864-5360-3.

- ^ Johann Strauss, Jr. in the United States, 1872. The Classical Music Guide Forums. Lance, Corlyss D.

- ^ "America and Johann Strauss." Austrian Information, volumes 51–54. Information Department of the Austrian Consulate General, 1998

- ^ "The Waltz King and the Land of Giants." Bill Morelock. 9 August 2005. Minnesota Public Radio.

- ^ "Johann Strauss II (1825–1899); AUT". Classical Archives. Retrieved 13 April 2009.

- ^ "Émile Waldteufel- Bio, Albums, Pictures – Naxos Classical Music". www.naxos.com.

- ^ "The Viennese Operetta". Retrieved 14 April 2009.

- ^ Jacob 1940, p. 226.

- ^ "Vienna Tickets – Johann Strauss". Retrieved 3 October 2008.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Rubey, Norbert. Seid umschlungen, Millionen!. Diletto Musicale, Doblinger.

- ^ Jacob 1940, p. 227.

- ^ Traubner 1983, p. 131.

- ^ a b Jacob 1940, p. 341.

- ^ "Willi Boskovsky, 81, Waltz Violinist, Dies", The New York Times, 24 April 1991.

- ^ Vienna Johann Strauß Orchestra Archived 3 February 1999 at archive.today

- ^ Weitlaner 2019, p. 118.

- ^ Jacob 1940, p. 363.

- ^ Crittenden, Camille. Johann Strauss and Vienna. Cambridge University Press. p. 89.

- ^ "Chronology of the Walt Disney Company (1963)". Polsson's WebWorld.

General and cited sources

edit- Fantel, Hans (1972). The Waltz Kings. William Morrow & Company. ISBN 978-0-688-00092-9.

- Gartenberg, Egon (1974). Johann Strauss: The End of an Era. Penn State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-01131-8.

- Jacob, Heinrich Eduard (1940) [1939]. Johann Strauss, Father and Son: A Century of Light Music. Freeport, NY: The Greystone Press. OCLC 607057509.

- Traubner, Richard (1983). Operetta: A Theatrical History. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-13232-9.

- Weitlaner, Juliana (2019). Johann Strauss: Father and Son: Their Illustrated Lives. Prague: Vitalis. ISBN 978-3-89919-648-1.

Further reading

edit- Gänzl, Kurt (2001). The Encyclopedia of Musical Theatre (3 volumes). New York: Schirmer Books. ISBN 978-0-02-864970-2.

External links

edit- A complete list of Strauss's compositions

- A complete list of compositions by Johann Strauss II compiled by the Johann Strauss Society of New York

- List of Strauss's stage works with date, theatre information and links

- List of Strauss works at the Index to Opera and Ballet Sources Online

- Free scores by Johann Strauss II at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)