This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (May 2014) |

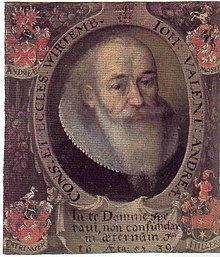

Johannes Valentinus Andreae (17 August 1586 – 27 June 1654), a.k.a. Johannes Valentinus Andreä or Johann Valentin Andreae, was a German theologian, who claimed to be the author of an ancient text known as the Chymische Hochzeit Christiani Rosencreutz anno 1459 (published in 1616, Strasbourg; in English Chymical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreutz in 1459). This became one of the three founding works of Rosicrucianism, which was both a legend and a fashionable cultural phenomenon across Europe in this period.

Johannes Valentinus Andreae | |

|---|---|

Johannes Valentinus Andreae | |

| Born | 17 August 1586 |

| Died | 27 June 1654 (aged 67) |

| Parent(s) | Johannes Andreae (1554–1601) Maria Moser |

Andreae was a prominent member of the Protestant utopian movement which began in Germany and spread across northern Europe and into Britain under the mentorship of Samuel Hartlib and John Amos Comenius. The focus of this movement was the need for education and the encouragement of sciences as the key to national prosperity. But like many vaguely-religious Renaissance movements at this time, the scientific ideas being promoted were often tinged with hermeticism, occultism and neo-Platonic concepts. The threats of heresy charges posed by rigid religious authorities (Protestant and Catholic) and a scholastic intellectual climate often forced these activists to hide behind fictional secret societies and write anonymously in support of their ideas, while claiming access to "secret ancient wisdom".

Life

editAndreae was born at Herrenberg, Württemberg, the son of Johannes Andreae (1554–1601), the superintendent of Herrenberg and later the abbot of Königsbronn. His mother Maria Moser went to Tübingen as a widow and was court apothecary 1607–1617. The young Andreae studied theology and natural sciences 1604–1606. He befriended Christoph Besold who encouraged Andreae's interest in esotericism. Ca. 1605 he wrote the first version of "The Chemical Wedding of Christian Rosekreutz". He was refused the final examination and church service, probably for attaching a pasquill (offensive, libelous note) to the chancellor Enzlin's door, on the occasion of his marriage. After that, he taught young nobles and hiked with his students through Switzerland, France, Austria and Italy. He visited Dillingen, a bastion of the Jesuits, whom he regarded as the Antichrist. In 1608 he returned to Tübingen. He came to know Tobias Hess, a Paracelsian physician with an interest in apocalyptic prophecy. From 1610 till 1612 Andreae traveled.

In 1612 he resumed his theological studies in Tübingen. After the final examination in 1614, he became deacon in Vaihingen an der Enz, and in 1620 priest in Calw. Here he reformed the school and social institutions, and established institutions for charity and other aids. To this end, he initiated the Christliche Gottliebende Gesellschaft ("Christian God-loving Society"). In 1628 he planned a "Unio Christiana". He obtained funds and brought effective help for the reconstruction of Calw, which was destroyed in the Battle of Nördlingen (1634) by the imperial troops and visited by pestilence. In 1639, he became preacher at the court and councillor of the consistory (Konsistorialrat) in Stuttgart, where he advocated a fundamental church reform. He became also a spiritual adviser to a royal princess of Württemberg.

Among other things, he promoted the Tübinger Stift, a hall of residence and teaching which was a seminary owned and supported by the Evangelical-Lutheran Church in Württemberg, in South West Germany. The Stift was founded as an Augustinian monastery in the Middle Ages, but after the Reformation (in 1536), Duke Ulrich turned the Stift into a seminary which served to prepare Protestant pastors for Württemberg. A prominent student of the Stift during this period was Johannes Kepler.

In 1646, Andreae was made a member of the Fruchtbringende Gesellschaft ("Fruitbearing Society"), where he got the company-nickname der Mürbe ("the soft"). In 1650, he assumed direction of the monasterial school Bebenhausen, and in 1654, he became abbot of the evangelical monasterial school of Adelberg. He died in Stuttgart.

Rosicrucianism

editHis role in the origin of the Rosicrucian legend is controversial. In his autobiography he claimed[citation needed] that the Chymische Hochzeit ("Chymical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreutz") was one of his works—as a "ludibrium", possibly meaning "lampoon". In his Menippus (1617) he argued that he wrote this fake document in his youth, around 1605. In his later works, Andreae treated alchemy as a subject of ridicule and placed it with music, art, theatre and astrology in the category of the 'less serious' sciences. It is uncertain how to interpret these statements. Was Andreae under pressure from the authorities because of his official relations as a clergyman, or had he in the meantime converted to a more homodox form of Lutheranism?

In a later phase of his life, Andreae expressed himself as a pious, orthodox Lutheran theologian who had nothing at all to do with the two great manifestoes of the secret society—the Fama fraternitatis or the Confessio fraternitatis. His lifelong commitment appears to have been to found a Societas Christiana or utopian learned brotherhood of those dedicated to a spiritual life, in the hope that they would initiate a second Reformation.

His writings and efforts provided a potent stimulus to Protestant intellectuals at the beginning of the seventeenth century, and he appears to have inspired the foundation of the Unio Christiana which was established in Nuremberg during 1628 by a few patricians and churchmen under the impetus of Johannes Saubert the Elder. This utopian society was later revived in Stuttgart in the early 1660s and another utopian brotherhood known as Antilia (a communal society reminiscent of the monastery) developed in the Baltic during the Thirty Years' War. The founders were inspired by both Baconian belief in experimental science and by Andreae's tracts. They later attempted to establish a colony on a small island in the Gulf of Riga, and considered immigrating to Virginia.[citation needed]

Priory of Sion

editDuring the 1960s, as part of a hoax claiming the existence of a medieval secret society, a set of documents of dubious authenticity, the Dossiers Secrets, was discovered in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BNF). One of the documents included an alleged list of "Grand Masters of the Priory of Sion", and Andreae was listed as the seventeenth Grand Master.

Works

edit- Compendium Mathematicum (1614)

- Chymische Hochzeit Christiani Rosencreutz Anno 1459 ("The chymical Wedding of Christian Rosencreutz"), published anonymously (1616)

- Menippus (1617)

- Invitatio Fraternitatis Christi (1617–1618)

- Peregrini in patria errores (1618)

- Reipublicae Christianopolitanae descriptio ("Description of the Republic of Christianopolis", "Beschreibung des Staates Christenstadt") (1619)

- Turris Babel (1619)

- De curiositatis pernicie syntagma (1620)

See also

edit- Esoteric Christianity

- Kabbalah

- Lectorium Rosicrucianum – Antonin Gadal – Catharose de Petri – Jan van Rijckenborgh

- Rosicrucianism

- Rosicrucian Fellowship – Max Heindel

- Rosicrucian Manifestos – Fama Fraternitatis – Confessio Fraternitatis – The Chymical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreutz – Parabola Allegory

References

edit- Donald R. Dickson, "Johann Valentin Andreae's Utopian Brotherhoods," Renaissance Quarterly, 49, 4 (1996): 760–802.

- Donald R. Dickson, The Tessera of Antilla: Utopian Brotherhoods and Secret Societies in the Early Seventeenth Century, Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers, 1998. ISBN 90-04-11032-1

- Roland Edighoffer, "Hermeticism in Early Rosicrucianism," in Gnosis and Hermeticism: From Antiquity to Modern Times, edited by Roelof van den Broek and Wouter J. Hanegraaff, State University of New York Press, 1998. ISBN 0-7914-3612-8

- Christopher McIntosh, The Rosicrucians: The History, Mythology, and Rituals of an Esoteric Order, 3rd revised edition, Samuel Weiser, York Beach, Maine, 1997. ISBN 0-87728-920-4

- John Warwick Montgomery, Cross and Crucible: Johann Valentin Andreae (1586–1654). Phoenix of the Theologians, 2 Vols. Martinus Nijhoff, the Hague, 1974. ISBN 90-247-5054-7

- John Warwick Montgomery, "The World-View of Johann Valentin Andreae," in Das Erbe des Christian Rosencreutz. Johann Valentin Andreae 1586–1986 und die Manifeste der Rosenkreuzerbruderschaft 1614–1616, Amsterdam: In de Pelikaan, 1988, pp. 152–169. ISBN 3-7762-0279-3

- Edward H. Thompson, "Introduction", in Johannes Valentin Andreae, Christianopolis, translated by Edward H. Thompson, Boston, Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1999. ISBN 0-7923-5745-0

- Frances A. Yates, The Rosicrucian Enlightenment, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1972. ISBN 0-415-26769-2