John Foster Dulles[a] (February 25, 1888 – May 24, 1959) was an American politician, lawyer, and diplomat who served as United States secretary of state under president Dwight D. Eisenhower from 1953 until his resignation in 1959. A member of the Republican Party, he was briefly a U.S. senator from New York in 1949. Dulles was a significant figure in the early Cold War era, who advocated an aggressive stance against communism throughout the world.

John Foster Dulles | |

|---|---|

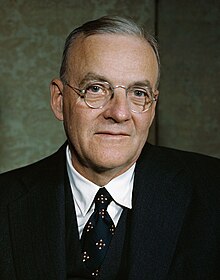

Dulles, c. 1949 | |

| 52nd United States Secretary of State | |

| In office January 26, 1953 – April 22, 1959 | |

| President | Dwight D. Eisenhower |

| Preceded by | Dean Acheson |

| Succeeded by | Christian Herter |

| United States Senator from New York | |

| In office July 7, 1949 – November 8, 1949 | |

| Appointed by | Thomas E. Dewey |

| Preceded by | Robert F. Wagner |

| Succeeded by | Herbert H. Lehman |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 25, 1888 Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Died | May 24, 1959 (aged 71) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse |

Janet Pomeroy Avery (m. 1912) |

| Children |

|

| Relatives | Dulles family |

| Education | Princeton University (BA) George Washington University (LLB) |

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Branch/service | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1917–1919 |

| Rank | Major |

| Battles/wars | World War I |

Born in Washington, D.C., Dulles joined the leading New York law firm of Sullivan & Cromwell after graduating from George Washington University Law School. His grandfather, John W. Foster, and his uncle, Robert Lansing, both served as U.S. secretary of state, while his brother, Allen Dulles, served as the director of central intelligence from 1953 to 1961. Dulles served on the War Industries Board during World War I and he was a U.S. legal counsel at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference. He became a member of the League of Free Nations Association, which supported American membership in the League of Nations. Dulles also helped design the Dawes Plan, which sought to stabilize Europe by reducing German war reparations. During World War II, Dulles was deeply involved in post-war planning with the Federal Council of Churches Commission on a Just and Durable Peace.

Dulles served as the chief foreign policy adviser to Thomas E. Dewey, the Republican presidential nominee in 1944 and 1948. He also helped draft the preamble to the United Nations Charter and served as a delegate to the UN General Assembly. In 1949, Dewey appointed Dulles a U.S. senator for New York. Dulles served for four months before his defeat in a special election. Despite having supported his political opponents, Dulles became a special advisor to president Harry S. Truman, with a focus on the Indo-Pacific region. In this role from 1950 to 1952, he became the primary architect of the Treaty of San Francisco, which ended World War II in Asia, the U.S.–Japan Security Treaty, which established the U.S.–Japan Alliance, and the ANZUS security treaty between Australia, New Zealand, and the United States.

In 1953, President Eisenhower chose Dulles as secretary of state. Throughout his tenure, Dulles favored a strategy of massive retaliation in response to Soviet aggression and concentrated on building and strengthening Cold War alliances, most prominently NATO. He was the architect of the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization, an anti-communist defensive alliance between the U.S. and several nations in and near Southeast Asia. He also helped instigate the 1953 Iranian coup d'état and the 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état. Dulles advocated support of the French in their war against the Viet Minh in Indochina, but rejected the Geneva Accords between France and the communists, instead supporting South Vietnam after the 1954 Geneva Conference. In 1959, suffering from cancer, Dulles resigned from office and died shortly after.

Early life and education

editDulles was born in Washington, D.C., eldest of five children of Presbyterian minister Allen Macy Dulles and his wife, Edith (née Foster). His paternal grandfather, John Welsh Dulles, had been a Presbyterian missionary in India. His maternal grandfather, John W. Foster, had been Secretary of State under Benjamin Harrison, and doted on Dulles and his brother Allen, who would later become the director of the Central Intelligence Agency. The brothers grew up in Watertown, New York and spent summers with their maternal grandfather in nearby Henderson Harbor. The brothers were also homeschooled, as their parents distrusted public education.[1][2][3]

Dulles attended Princeton University and graduated as a member of Phi Beta Kappa in 1908. At Princeton, Dulles competed on the American Whig-Cliosophic Society debate team and was a member of University Cottage Club.[4][5] He then attended the George Washington University Law School in Washington, D.C.

Early career

editUpon passing the bar examination, Dulles joined the New York City law firm of Sullivan & Cromwell, where he specialized in international law. After US entry into World War I, Dulles tried to join the Army, but was rejected because of poor eyesight. Instead, Dulles received an army commission as major on the War Industries Board. Dulles later returned to Sullivan & Cromwell and became a partner with an international practice.[6]

In 1917, Dulles’ uncle, Robert Lansing, the then-Secretary of State, recruited him to travel to Central America.[7] Dulles advised Washington to support Costa Rica's dictator, Federico Tinoco, on the grounds that he was anti-German, and also encouraged Nicaragua's dictator, Emiliano Chamorro, to issue a proclamation suspending diplomatic relations with Germany. In Panama, Dulles offered waiver of the tax imposed by the United States on the annual Canal fee, in exchange for a Panamanian declaration of war on Germany.[8]

Interwar and World War II activities

editVersailles Peace Conference

editIn 1918, President Woodrow Wilson appointed Dulles as legal counsel to the United States delegation to the Versailles Peace Conference, where he served under his uncle, Secretary of State Robert Lansing. Dulles made an early impression as a junior diplomat. While some recollections indicate he clearly and forcefully argued against imposing crushing reparations on Germany, other recollections indicate he ensured Germany's reparation payments would extend for decades as perceived leverage militating against future German-born hostilities. Afterwards, he served as a member of the War Reparations Committee at Wilson's request. He was also an early member, along with Eleanor Roosevelt, of the League of Free Nations Association, founded in 1918, and after 1923 known as the Foreign Policy Association, which supported American membership in the League of Nations.[9]

Dawes Plan

editAs a partner in Sullivan & Cromwell, Dulles expanded upon his late grandfather Foster's expertise, specializing in international finance. He played a major role in designing the Dawes Plan, which reduced German reparations payments and temporarily resolved the reparations issue by having American firms lend money to German states and private companies. Under that compromise, the money was invested and the profits sent as reparations to Britain and France, which used the funds to repay their own war loans from the U.S. In the 1920s Dulles was involved in setting up a billion dollars' worth of these loans.[10]

After the Wall Street Crash of 1929, Dulles's previous practice brokering and documenting international loans ended. After 1931 Germany stopped making some of its scheduled payments. In 1934 Germany unilaterally stopped payments on private debts of the sort that Dulles was handling. After the Nazi Party came to power, Dulles expressed sympathies for Adolf Hitler, requiring his legal staff in Berlin to sign "Heil Hitler" on all of Sullivan & Cromwell's outgoing mail; fearful of the optics, Sullivan & Cromwell's junior partners forced Dulles to cut all business ties with Germany in 1935. Nonetheless, Dulles and his wife continued to visit Germany until 1939.[11] He was prominent in the religious peace movement and an isolationist, but the junior partners were led by his brother Allen, so he reluctantly acceded to their wishes.[12][13]

Fosdick controversy

editDulles, a deeply religious man, attended numerous international conferences of churchmen during the 1920s and 1930s. In 1924, he was the defense counsel in the church trial of Reverend Harry Emerson Fosdick, who had been charged with heresy by opponents in his denomination. The event sparked the continuing Fundamentalist–Modernist Controversy in the international Christian Churches over the literal interpretation of Scripture against the newly developed "Historical-Critical" method including recent scientific and archeological discoveries. The case was settled when Fosdick, a liberal Baptist, resigned his pulpit in the Presbyterian Church congregation, which he had never joined.[14]

Six Pillars of Peace

editDuring the Second World War, Dulles engaged in Post-War Planning under the auspices of the Federal Council of Churches Commission on a Just and Durable Peace. Appointed in December 1940 at the behest of the theologian Henry P. Van Dusen, Dulles developed a vision of post-war order underpinned by a federal world government, taking inspiration from the ecumenical ideology of liberal Mainline Protestantism and the United States' experiences with federalism. In essence, Dulles sought to persuade allied war leaders to work toward reviving a more robust League of Nations. The core elements of this vision were spelled out in March 1943 with the publication of the book Six Pillars of Peace. Dulles was largely unsuccessful in persuading Franklin Delano Roosevelt to embrace such a radical platform, as the United States would issue the more moderate Moscow Declaration, but his work helped to build widespread consensus about the need for a United Nations.[15]

Advisor to Thomas Dewey

editDulles was a prominent Republican and a close associate of Governor Thomas E. Dewey of New York, who became the Republican presidential nominee in the elections of 1944 and 1948. During the 1944 and the 1948 campaigns, Dulles served as Dewey's chief foreign policy adviser. In 1944, Dulles took an active role in establishing the Republican plank calling for the establishment of a Jewish commonwealth in The British Mandate for Palestine.[16]

In 1945, Dulles participated in the San Francisco Conference as an adviser to Arthur H. Vandenberg and helped draft the preamble to the United Nations Charter. He attended the United Nations General Assembly as a United States delegate in 1946, 1947, and 1950.

Dulles strongly opposed the American atomic attacks on Japan. In the immediate aftermath of the bombings, he drafted a public statement that called for international control of nuclear energy under United Nations auspices. He wrote:[17]

If we, as a professedly Christian nation, feel morally free to use atomic energy in that way, men elsewhere will accept that verdict. Atomic weapons will be looked upon as a normal part of the arsenal of war and the stage will be set for the sudden and final destruction of mankind.

Dulles never lost his anxiety about the destructive power of nuclear weapons, but his views on international control and on employing the threat of atomic attack changed in the face of the Berlin blockade, the Soviet detonation of an atomic bomb, and the advent of the Korean War. They convinced him that the communist bloc was pursuing expansionist policies.[18]

In the late 1940s, as a general conceptual framework for contending with world communism, Dulles developed the policy known as rollback to serve as the Republican Party's alternative to the Democrats' containment model. It proposed taking the offensive to push communism back, rather than to contain it within its areas of control and influence.[19]

U.S. Senator

editDewey appointed Dulles to the United States Senate to replace the Democratic incumbent Robert F. Wagner, who had resigned for ill health. Dulles served from July 7 to November 8, 1949. He lost the 1949 special election to finish the term to Democratic nominee Herbert H. Lehman.[20]

In 1950, Dulles published War or Peace, a critical analysis of the American policy of containment, which was favored by the foreign policy elite in Washington, particularly in the Democratic administration of Harry S. Truman, whose foreign policy Dulles criticized and instead advocated a policy of "liberation."[21]

Advisor to Harry Truman

editDespite being a prominent Republican and having been a close advisor to Truman's opponent Dewey, Dulles became a trusted advisor of Harry Truman, especially on the issue of what to do with Japan, which was still under U.S. military occupation.[22] In his role as an external "consultant" to Truman's State Department, Dulles became the key architect of the 1952 San Francisco Peace Treaty which ended the U.S. occupation of Japan, as well as the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty, which ensured that Japan would remain firmly in the U.S. camp in the Cold War and allowed the continuing maintenance of U.S. military bases on Japanese soil.[23]

In 1951, Dulles also helped initiate the ANZUS Treaty for mutual protection with Australia and New Zealand.

Possible Chief Justice nomination

editFollowing the 1953 death of Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson, President Eisenhower considered appointing Dulles in his place. In his later life Eisenhower is said to have considered only two men for the job: Dulles and eventual nominee Earl Warren.[24] The Evening Star in fact initially viewed Dulles as the third most likely candidate after Warren and Thomas E. Dewey,[25] while some Republican insiders at the time of Vinson's death actually thought Dulles was more likely to be chosen for the post than Warren.[26] Dulles was viewed by the press as too favourable to big business,[27] and in Eisenhower's own memoirs as too old to potentially wield significant influence upon the Court.[24] Besides the issue of age, Eisenhower did not want to deprive himself of Dulles's valuable contributions in the field of foreign policy.[24]

U.S. Secretary of State

editWhen Dwight Eisenhower succeeded Truman as president in January 1953, Dulles was appointed and confirmed as his Secretary of State. His tenure as Secretary was marked by conflict with communist governments worldwide, especially the Soviet Union; Dulles strongly opposed communism, calling it "Godless terrorism."[28] Dulles's preferred strategy was containment through military build-up and the formation of alliances (dubbed "pactomania").

Dulles was a pioneer of the strategies of massive retaliation and brinkmanship. In an article written for Life magazine, Dulles defined his policy of brinkmanship: "The ability to get to the verge without getting into the war is the necessary art."[29]

Dulles's hard line alienated many leaders of non-aligned countries when on June 9, 1955, he argued in a speech that "neutrality has increasingly become obsolete and, except under very exceptional circumstances, it is an immoral and shortsighted conception."[30] In a June 1956 speech in Iowa, Dulles declared non-alignment to be "immoral", further castigating the Non-Aligned Movement.[31] Throughout the 1950s, Dulles was in frequent conflict with non-aligned statesmen who he deemed were too sympathetic to communism, including India's V. K. Krishna Menon.

Iran

editOne of his first major policy shifts towards a more aggressive position against communism occurred in March 1953, when Dulles supported Eisenhower's decision to direct the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), then headed by his brother Allen Dulles, to draft plans to overthrow Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh of Iran.[32] That led directly to the coup d'état via Operation Ajax in support of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who regained his position as the Shah of Iran.

Vietnam

editDuring the First Indochina War, Dulles stated that he expected a French victory against the communist Viet Minh forces, stating, "I do not expect that there is going to be a communist victory in Indochina".[33] Dulles worked to reduce French influence in Vietnam and asked the United States to attempt to co-operate with the French in the aid of strengthening Diem's army. Over time, Dulles concluded that he had to "ease France out of Vietnam."[34]

In 1954, at the height of the Battle of Dien Bien Phu, Dulles helped plan and promote Operation Vulture, a proposed B-29 aerial assault on the communist Viet Minh siege positions to relieve the beleaguered French Army. President Eisenhower made American participation reliant on British support, but Foreign Secretary Sir Anthony Eden was opposed to it and so Vulture was canceled over Dulles's objections.[35][36] French Foreign Minister Georges Bidault later said that Dulles had offered him the use of atomic bombs to end the siege.[37]

At the 1954 Geneva Conference, which concerned the breakup of French Indochina, he forbade any contact with the Chinese delegation and refused to shake hands with Zhou Enlai, the lead Chinese negotiator. Dulles also opposed the conference's plan to partition the country of Vietnam and hold elections for a unified government, insisting that the anti-communist State of Vietnam should remain the legitimate Vietnamese government. He subsequently left to avoid direct association with the negotiations; Dulles's exit contributed to the Geneva Conference's failure to resolve the conflict in Vietnam.[38][39]

Asia and the Pacific

editAs Secretary of State, Dulles carried out the "containment" policy of neutralizing the Taiwan Strait during the Korean War.[40] Later, at Geneva, Dulles objected to any proposals by China and the Soviet Union for a diplomatic reunification of Korea, thus leaving the Korean conflict unresolved.[41]

In 1954, Dulles designed the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO), providing for collective action against aggression. The treaty was signed by representatives of Australia, Britain, France, New Zealand, Pakistan, the Philippines, Thailand, and the United States.

In 1958, Dulles authorized the Secretary of the Air Force to state publicly that the United States was prepared to use nuclear weapons in a conflict with China over the islands of Quemoy and Matsu.[42]

After having resisted revision for many years, from 1957 to 1959, Dulles oversaw the renegotiation of a revised version of the U.S.–Japan Security Treaty, which was eventually ratified in 1960, after his death.[43]

Guatemala

editThe same year, Dulles participated in the instigation of a military coup by the Guatemalan army through the CIA by claiming that the democratically elected Guatemalan President Jacobo Árbenz's government and the Guatemalan Revolution were veering toward communism. Dulles had previously represented the United Fruit Company as a lawyer.[44] Thomas Dudley Cabot, former CEO of United Fruit, held the position of Director of International Security Affairs in the State Department. John Moore Cabot, a brother of Thomas Dudley Cabot, was secretary of Inter-American Affairs during much of the coup planning in 1953 and 1954.[45]

Egypt

editIn November 1956, Dulles strongly opposed the Anglo-French invasion of the Suez Canal zone in response to Egypt's nationalization of the canal. During the most crucial days, Dulles was hospitalized after surgery and did not participate in the U.S. administration's decision making. By 1958, he had become an outspoken opponent of Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser and prevented Nasser's government from receiving arms from the United States. That policy allowed the Soviet Union to gain influence in Egypt.[46]

Personal life

editFamily

editBoth his grandfather, Foster, and his uncle, Robert Lansing, the husband of Eleanor Foster, had held the position of Secretary of State. His younger brother, Allen Welsh Dulles, served as Director of Central Intelligence under Dwight D. Eisenhower, and his younger sister Eleanor Lansing Dulles was noted for her work in the successful reconstruction of the economy of post-war Europe during her twenty years with the State Department.

On June 26, 1912, Dulles married Janet Pomeroy Avery (1891–1969), granddaughter of Theodore M. Pomeroy, a former United States Congressman and Speaker of the House of Representatives.[47] They had two sons and a daughter. Their older son John W. F. Dulles (1913–2008) was a professor of history and specialist in Brazil at the University of Texas at Austin.[48] Their daughter Lillias Dulles Hinshaw (1914–1987) became a Presbyterian minister. Their son Avery Dulles (1918–2008) converted to Roman Catholicism, entered the Jesuit order, and became the first American theologian to be appointed a Cardinal.

Non-governmental organizations

editDulles served as the chairman and cofounder of the Commission on a Just and Durable Peace of the Federal Council of Churches of Christ in America (later the National Council of Churches), the chairman of the board for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, and a trustee of the Rockefeller Foundation from 1935 to 1952. Dulles was also a founding member of Foreign Policy Association and Council on Foreign Relations.

Death

editDulles developed colon cancer, for which he was first operated on in November 1956 when it had caused a bowel perforation.[49] He experienced abdominal pain at the end of 1958 and was hospitalized with a diagnosis of diverticulitis. In January 1959, Dulles returned to work, but with more pain and declining health underwent abdominal surgery in February at Walter Reed Army Medical Center when the cancer's recurrence became evident. After recuperating in Florida, Dulles returned to Washington for work and radiation therapy. With further declining health and evidence of bone metastasis, he resigned from office on April 15, 1959.[49]

Dulles died at Walter Reed on May 24, 1959, at the age of 71.[50] Funeral services were held in Washington National Cathedral on May 27, 1959, and he was buried at Arlington National Cemetery, in Arlington County, Virginia.[51]

Legacy

editDulles was posthumously awarded the Medal of Freedom and the Sylvanus Thayer Award in 1959. A central West Berlin road was named John-Foster-Dulles-Allee in 1959 with a ceremony attended by Christian Herter, Dulles's successor as Secretary of State.

The Washington Dulles International Airport in Dulles, Virginia and John Foster Dulles High, Middle, and Elementary Schools in Sugar Land, Texas (including the street (Dulles Avenue) where the school campuses are located), were named in his honor, as is John Foster Dulles Elementary School in Cincinnati, Ohio, and a school in Chicago, Illinois.[52] New York named the Dulles State Office Building in Watertown, New York in his honor. In 1960 the U.S. Post Office Department issued a commemorative stamp honoring Dulles. At Princeton University, Dulles's alma mater, a section of Firestone Library is dedicated to Dulles, named the John Foster Dulles Library of Diplomatic History, which houses, among many American diplomatic documents and books, the personal documents of John Foster Dulles. The library was built in 1962.[53]

This quote is sometimes misattributed to Dulles: "The United States of America does not have friends; it has interests." The words were spoken by President Charles de Gaulle of France, and the misquotation may be attributed to Dulles's visit to Mexico in 1958, where anti-American protesters carried signs bearing de Gaulle's quote.[54]

Popular culture

editDulles was named Time magazine's Man of the Year for 1954.[55]

Entertainer Carol Burnett rose to prominence in 1957 singing a novelty song, "I Made a Fool of Myself Over John Foster Dulles".[56] When asked about the song on Meet the Press, Dulles responded with good humor: "I never discuss matters of the heart in public."[57]

See also

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ Ferrell, Robert H. (1963). The American Secretaries of State and Their Diplomacy: John Foster Dulles Cooper Square Publishers, New York, NY, p. 4

- ^ Goold-Adams, Richard (1962). The Time of Power: A Reappraisal of John Foster Dulles Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, p. 24

- ^ "Q&A with Stephen Kinzer | C-SPAN.org". www.c-span.org. Retrieved March 17, 2024.

- ^ "Freshman Debate". Daily Princetonian. May 19, 1905. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ^ "About the Cottage Club". University Cottage Club. Retrieved January 3, 2021.

- ^ Pruessen, pp 15–20.

- ^ "DULLES, JOHN FOSTER: Papers, 1950–1961" (PDF). DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER LIBRARY. Retrieved February 28, 2021.

- ^ Pruessen, pp 20–28.

- ^ Pruessen, pp 29–57.

- ^ Pruessen, pp 87–108.

- ^ Talbot, David (October 13, 2015). The Devil's Chessboard: Allen Dulles, the CIA, and the Rise of America's Secret Government. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-227621-6.

- ^ Peter Grose, Gentleman Spy, The Life of Allen Dulles (1994), pp. 91–93, 119–22

- ^ Ronald W. Pruessen, John Foster Dulles: The Road to Power (1982), pp. 115, 123

- ^ Harold H. Vences, "The Controversy Surrounding the Ministry of Harry Emerson Fosdick in the First Presbyterian Church of New York City, 1922–1925." (1972) Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects. 741. online.

- ^ Andrew Preston, Sword of the Spirit, Shield of Faith (2012), pp. 384–409

- ^ Isaac Alteras, Eisenhower and Israel: U.S.-Israeli Relations, 1953–1960 (University Press of Florida, 1993), ISBN 0-8130-1205-8, pp. 53–55

- ^ John Lewis Gaddis (1999). Cold War Statesmen Confront the Bomb: Nuclear Diplomacy Since 1945. Oxford University Press. p. 65. ISBN 9780198294689.

- ^ Neal Rosendorf, "John Foster Dulles' Nuclear Schizophrenia," in John Lewis Gaddis et al., Cold War Statesmen Confront the Bomb: Nuclear Diplomacy since 1945 (Oxford University Press, 1999), pp. 64–69

- ^ Detlef Junker, Philipp Gassert, and Wilfried Mausbach, eds., The United States and Germany in the Era of the Cold War, 1945–1968: A Handbook, Vol. 1: 1945–1968 (Cambridge University Press, 2004)[page needed]

- ^ Pruessen, 398–403.

- ^ Pruessen, 433–441.

- ^ Kapur, Nick (2018). Japan at the Crossroads: Conflict and Compromise after Anpo. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 28. ISBN 9780674988484.

- ^ Kapur, Nick (2018). Japan at the Crossroads: Conflict and Compromise after Anpo. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 12, 38–39. ISBN 9780674988484.

- ^ a b c Richardson, Elmo (1985). The Presidency of Dwight D. Eisenhower. University Press of Kansas. p. 108. ISBN 0700602674.

- ^ Hines, William (September 13, 1953). "Past Chief Justices' Record Will Help Eisenhower Pick Successor". Evening Star. Washington, District of Columbia. p. A-27.

- ^ ‘Dulles May Get Vinson’s Post’; The Philadelphia Inquirer, September 9, 1953, p. 14

- ^ Brandt, Raymond P. (September 27, 1953). "A New Chief Justice: Eisenhower Must Make Historic Decision – Will President Appoint the Best Man Available or Will He Listen to Partisan Politicians". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. p. 1C.

- ^ Gary B. Nash, et al., The American People, Concise Edition Creating a Nation and a Society, Combined Volume (6th Edition). New York: Longman, 2007, p. 829

- ^ Stephen E. Ambrose (2010). Rise to Globalism: American Foreign Policy Since 1938, Ninth Revised Edition. Penguin. p. 109. ISBN 9781101501290.

- ^ Ian Shapiro (2009). Containment: Rebuilding a Strategy against Global Terror. Princeton University Press. pp. 145–. ISBN 978-1400827565.

- ^ Rakove, Robert B. (August 24, 2015). "The Rise and Fall of Non-Aligned Mediation, 1961–6". The International History Review. 37 (5): 991–1013. doi:10.1080/07075332.2015.1053966. S2CID 155027250. Retrieved March 14, 2023.

- ^ The C.I.A. in Iran

- ^ Hearts and Minds (1974), January 15, 2018, retrieved January 28, 2024

- ^ Immerman, Richard H. (1999). John Foster Dulles: Piety, Pragmatism, and Power in U.S. Foreign Policy. Wilmington, Delaware: Scholarly Resources. p. 98. ISBN 9780842026017.

- ^ Kowert, Paul (2002), Groupthink or deadlock: when do leaders learn from their advisors? (illustrated ed.), SUNY Press, pp. 67–68, ISBN 978-0-7914-5249-3

- ^ Tucker, Spencer (1999), Vietnam (illustrated ed.), Routledge, p. 76, ISBN 978-1-85728-922-0

- ^ Duiker, William (1994). U. S. Containment Policy and the Conflict in Indochina. Stanford University Press. p. 166.

- ^ Logevall, Fredrik (2012). Embers of War: The Fall of an Empire and the Making of America's Vietnam. random House. pp. 555–58. ISBN 978-0-679-64519-1.

- ^ Kinzer, Stephen (October 1, 2013). The Brothers: John Foster Dulles, Allen Dulles, and Their Secret World War. Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4299-5352-8.

- ^ Immerman, Richard H. John Foster Dulles Piety, Pragmatism, and Power in U.S. Foreign Policy (Biographies in American Foreign Policy). New York: SR Books, 1998. p. 37

- ^ Bailey, Sydney D. (July 13, 1992). The Korean Armistice. Springer. ISBN 978-1-349-22104-2.

- ^ Rhodes, Richard (1995). Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb (First ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 569–70. ISBN 0-684-80400-X.

- ^ Kapur, Nick (2018). Japan at the Crossroads: Conflict and Compromise after Anpo. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 40. ISBN 9780674988484.

- ^ Cohen, Rich (2012). The Fish that Ate the Whale. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux. p. 186.

- ^ Dube, Arindrajit, Kaplan, Ethan, and Suresh Naidu (2011), Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126 (3) pp. 1375–1409, Coups, Corporations, and Classified Information

- ^ Cole Christian Kingseed (1995). Eisenhower and the Suez Crisis of 1956. LSU Press. p. 117. ISBN 9780807140857.

- ^ Pomeroy, Bill. "Honorable Theodore Medad POMEROY". rootsmagic.com. American Pomeroy Historic Genealogical Association. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

- ^ "90-year-old Still Active at University" Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, The Daily Texan

- ^ a b Lerner BH (November 20, 2006). When Illness Goes Public: Celebrity Patients and How We Look at Medicine. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 2006. p. 81ff. ISBN 978-0-8018-8462-7.

- ^ "Death of John Foster Dulles - 1959 Year In Review - Audio - UPI.com". UPI. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ "Burial Detail: Dulles, John F. (Section 21, Grave S-31)". ANC Explorer. Arlington National Cemetery. (Official website).

- ^ "J.F. Dulles Elementary". Archived from the original on January 29, 2009. Retrieved December 18, 2008.

- ^ "Dulles Library of Diplomatic History". etcweb.princeton.edu. Archived from the original on June 2, 2010. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- ^ "Dulles in Rio". New York Times. August 10, 1958.

- ^ "Man of the Year – TIME". September 30, 2007. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ Adir, Karin (1988). The Great Clowns of American Television. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. pp. 51–2. ISBN 9780786413034.

- ^ Colbert, Stephen (March 27, 2024). "Carol Burnett Was "The World's Worst Guest" On Johnny Carson's "Tonight Show"". The Late Show with Stephen Colbert. YouTube. Retrieved March 27, 2024.

Further reading

edit- Anderson, David L. "J. Lawton Collins, John Foster Dulles, and the Eisenhower Administration's "Point of No Return" in Vietnam." Diplomatic History 12.2 (1988): 127–147.

- Challener, Richard D. "The Moralist as Pragmatist: John Foster Dulles as Cold War Strategist." in The Diplomats, 1939–1979 (Princeton University Press, 2019) pp. 135–166. online

- Dingman, Roger. "John Foster Dulles and the Creation of the South-East Asia Treaty Organization in 1954." International History Review 11.3 (1989): 457–477.

- Gerson, Louis L. John Foster Dulles (1967), a major scholarly study online

- Goold-Adams, Richard. John Foster Dulles; a reappraisal (1962) online

- Greene, Daniel P. O'C. "John Foster Dulles and the End of the Franco-American Entente in Indochina." Diplomatic History 16.4 (1992): 551–572.

- Guhin, Michael A. John Foster Dulles: a statesman and his times (Columbia University Press, 1972) online

- Hoopes Townsend, Devil and John Foster Dulles (1973) ISBN 0-316-37235-8. a scholarly biography online

- Inboden III, William Charles. "The soul of American diplomacy: Religion and foreign policy, 1945–1960" (PhD diss. Yale University, 2003) online.

- Immerman, Richard H. John Foster Dulles: Piety, Pragmatism, and Power in U.S. Foreign Policy (1998) ISBN 0-8420-2601-0 online

- Immerman, Richard H. "John Foster Dulles." Dictionary of American Biography (1980) online

- Kinzer, Stephen. The Brothers: John Foster Dulles, Allen Dulles, and Their Secret World War. Times Books (2013). ISBN 0805094970.

- Marks, Frederick. Power and Peace: The Diplomacy of John Foster Dulles (1995). ISBN 0-275952320. online

- Mosley, Leonard. Dulles : a biography of Eleanor, Allen and John Foster Dulles and their family network (1978) online

- Mulder, John M. "The Moral World of John Foster Dulles: A Presbyterian Layman and International Affairs." Journal of Presbyterian History 49.2 (1971): 157–182. online

- Nelson, Anna Kasten. "John Foster Dulles and the Bipartisan Congress." Political Science Quarterly 102.1 (1987): 43–64. online

- Pruessen, Ronald W. John Foster Dulles: The Road to Power (1982), The Free Press ISBN 0-02-925460-4 online

- Ruane, Kevin. "Agonizing Reappraisals: Anthony Eden, John Foster Dulles and the Crisis of European Defence, 1953–54." Diplomacy and Statecraft 13.4 (2002): 151–185.

- Snyder, William P. "Dean Rusk to John Foster Dulles, May–June 1953: The Office, the First 100 Days, and Red China." Diplomatic History 7.1 (1983): 79–86.

- Stang, Alan. The Actor: The True Story of John Foster Dulles, Secretary of State, 1953–1959. Belmont, Mass.: Western Islands (1968). OCLC 434600.

- Toulouse, Mark G. The Transformation of John Foster Dulles: From Prophet of Realism to Priest of Nationalism. Mercer University Press (1985).

- Toulouse, Mark G. "The Development of a Cold Warrior: John Foster Dulles and the Soviet Union, 1945–1952." American Presbyterians, vol. 63, no. 3 (1985), pp. 309–322. JSTOR 23330558.

- Tudda, Chris. The Truth is Our Weapon: The Rhetorical diplomacy of Dwight D. Eisenhower and John Foster Dulles (2006)

- Wilsey, John D. God's Cold Warrior: The Life and Faith of John Foster Dulles (2021). ISBN 978-0802875723.

External links

edit- United States Congress. "John Foster Dulles (id: D000522)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Works by John Foster Dulles at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about John Foster Dulles at the Internet Archive

- A film clip "Longines Chronoscope with John Foster Dulles (February 1, 1952)" is available for viewing at the Internet Archive

- John Foster Dulles Papers at the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, Princeton University

- Papers of John Foster Dulles, Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library

- Annotated bibliography for John Foster Dulles from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues Archived August 28, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- FBI files on John Foster Dulles at the Internet Archive

- Newspaper clippings about John Foster Dulles in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- John Foster Dulles (Radio Reports partially in German) from the archive of the Österreichische Mediathek