John Gregory Jacobs (September 30, 1947 – October 20, 1997)[1] was an American student and anti-war activist in the 1960s and early 1970s. He was a leader in both Students for a Democratic Society and the Weatherman group, and an advocate of the use of violent force to overthrow the government of the United States. A fugitive after 1970, he died in 1997 in Canada.

John Jacobs | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | September 30, 1947 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Died | October 20, 1997 (aged 50) Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada |

| Education | Columbia University |

| Known for | Political activism |

Early life

editJohn Jacobs was born to Douglas and Lucille Jacobs, a prominent leftist Jewish couple, in New York state in 1947. He had an older brother, Robert. His father was a well-known leftist journalist who had been one of the first Americans to report on the Spanish Civil War. His parents later moved to Connecticut, where his father owned a bookstore. His childhood appeared to have been happy, and he was close to his parents.[1]

In high school, Jacobs began to read Marxist philosophy heavily, and was deeply interested in the Russian Revolution of 1917. He also admired Che Guevara.[1]

Jacobs graduated from high school in 1965 and enrolled at Columbia College of Columbia University. During the summer between high school and college, he lived in New York City and worked for a left-wing newspaper. Politically active in leftist political circles, Jacobs became acquainted with a large number of progressive intellectuals who further stimulated growth in his political ideology.[1] For a brief time, he belonged to the Progressive Labor Party (PL), at the time a Maoist communist party.[2][3][4] His first semester at Columbia, Jacobs met fellow freshman Mark Rudd, and the two became friends.[1]

Rise and role in Students for a Democratic Society

editJ.J., as most people at Columbia called him, soon joined Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). The Columbia University chapter of SDS had been founded in the 1950s as part of the Student League for Industrial Democracy, the youth arm of the League for Industrial Democracy (a social democratic organization co-founded by Jack London, Norman Thomas, Upton Sinclair and others). The chapter had sputtered for years, but became active in 1965 when it became known as SDS.[5] Jacobs became very active in the group. A series of protests against on-campus military, CIA and corporate recruitment and ROTC induction ceremonies rocked Columbia's campus for the next two years.[6] Jacobs organized a protest in February 1967 against CIA recruiting at Columbia. Initially, the SDS chapter disavowed the action. But when Jacobs' sit-in proved popular among Columbia students, SDS claimed J.J. as one of their own. The CIA protest led to Jacobs' rapid rise within the chapter.[2][5] The protests led Columbia President Grayson L. Kirk to ban indoor protests at Columbia beginning in September 1967.[6]

In March 1967, SDS member Bob Feldman accidentally discovered documents in a campus library detailing Columbia's affiliation with the Institute for Defense Analyses (IDA), a weapons research think-tank affiliated with the Department of Defense. Jacobs participated in the protests against the IDA, and was put on academic probation for violating President Kirk's ban on indoor protests.[2][5][7] Despite its growing influence on campus, the SDS chapter was deeply divided. One group of SDSers, called the "Praxis Axis," advocated more organizing and nonviolence. A second group, the "Action Faction," called for more aggressive action. In the early spring 1968, the Action Faction took control of Columbia University's SDS chapter. Jacobs was an active member of the Action Faction, and soon became one of its leaders.[1][5][6][8][9] When Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968, riots broke out in many American cities. Jacobs wandered the streets of Harlem alone for most of the night, thrilled by the violence and inability of the police to maintain order.[1] He adopted Georges Danton's dictum of "Audacity, audacity, and more audacity!" as his own motto.[4]

Columbia protests of 1968

editThe opportunity for Jacobs to participate more fully in direct action came just days after King's death. Columbia University officials were planning to build a new gymnasium on the south side of the campus. The building, which would have straddled a hill, would have two entrances—one on the north, upper side for students and one on the south, lower side for residents of Morningside Heights, a mostly African American neighborhood. To many students and local residents, it seemed as if Columbia were permitting blacks to use the gym, but only if they entered through the back door. On April 23, 1968, Rudd, Jacobs, and other members of Columbia's SDS chapter led a group of about 500 people in a protest against the gymnasium at the university Sundial. Part of the crowd attempted to take over Low Memorial Library, but were repulsed by a counter-demonstration of conservative students. Some students tore down the fence surrounding the construction site, and were arrested by New York City police. Rudd then shouted that the crowd should seize Hamilton Hall. The mob took over the building, taking a dean hostage. A number of militant young African Americans from Harlem (rumored to be carrying guns) entered the building throughout the night and ordered the white students out. The Caucasian students seized Low Memorial Library. Over the next week, more than 1,000 Columbia students joined the protest and seized three more buildings. Jacobs led the seizure of Mathematics Hall. Among the protesters was Tom Hayden, who arrived from Newark, New Jersey, where he had been organizing poor inner-city residents. Rudd, Jacobs, Hayden and others organized communes inside the buildings, and educated the students in the theories of Marxism, racism, and imperialism. Columbia University refused to grant the protesters' demands regarding the gymnasium or amnesty for those who had seized the buildings. When the police were sent in to clear the buildings after a week, they brutally beat and clubbed hundreds of students. Jacobs suggested putting Columbia's rare Ming Dynasty vases in the windows to prevent sniper attacks, and pushing police out of windows. Black students in Hamilton Hall had contacted civil rights lawyers, who had arranged to be on-site during the arrests and for the students to leave Hamilton Hall peacefully. Angered by the lack of police violence, Jacobs set fire to a professor's office in Hamilton, an incident later blamed on the police.[10] Thousands of students went on strike the next week, refusing to attend classes, and the university canceled final exams. The events catapulted Rudd into national prominence, and Rudd and Jacobs became national leaders in SDS.[1][11][12][13] Jacobs began using the phrase "bring the war home," and it was widely adopted within the anti-war movement.[5]

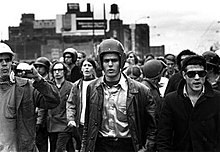

As college students across America began demanding "two, three, many Columbias,"[14] Jacobs became a recognized national leader of SDS and looked to by those who saw violence as the only way to respond to the governing political and economic system of the day.[1][9] Jacobs began to look the part of a counterculture leader as well. In the middle of 1968, he began wearing tight jeans, a leather jacket, and a gold chain with a lion's tooth, and slicked his hair back 1950s-style to purposefully distinguish himself from the clean-cut, middle-class students who attended most anti-war protests.[15] He became one of SDS' earliest and most prominent ideological thinkers,[4][16] and was widely recognized as a charismatic persuasive speaker.[3][4]

At the SDS national convention in East Lansing, Michigan, in June 1968, Jacobs' thinking began to become even more radical. The East Lansing convention is best known for the interminable debates and ferocious parliamentary battles between the SDS National Office leadership (led by Michael Klonsky and Bernardine Dohrn) and the delegates from PL-controlled SDS chapters around the country.[5]

Robin Palmer, an ex-Yippie had drifted into SDS.[17] Palmer argued, contrary to current SDS thinking, that President Richard Nixon's "silent majority" did exist. Most Americans, Palmer said, wouldn't oppose imperialism, militarism and capitalism if they were only shown the truth. Rather, most Americans knew the truth, and supported these ideologies actively and whole-heartedly. One of the Old Left's slogans had been "Serve the People." Convinced Palmer was correct, Jacobs proposed at the June 1968 convention that SDS adopt the slogan "Serve the People Shit" to reflect the public's support for greed and war.[4]

Role in Weatherman

editSDS had opposed the call for mass demonstrations at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, Illinois. The group felt that mass demonstrations and electoral politics were not effective as a means of influencing national policy. But when the demonstrations proved popular and provoked a heavy-handed police response (as SDS predicted), the organization moved quickly to take credit for the protests.[5]

But SDS itself was suffering from extreme factionalism. Since 1963, the Progressive Labor Party (PL) had been infiltrating its members into SDS in the hopes of convincing SDSers to join the party. Although only a tiny minority of SDS membership nationwide, PL supporters (with the support of the national party) often constituted a quarter or more of the delegates to national SDS conventions. Strongly disciplined and skilled at 'entryism' and using parliamentary procedure, the PL supporters sought to seize control of SDS and turn the organization to the party's goals.[5][16][18][19]

SDS leadership subsequently adopted a new policy in 1968 aimed at ending the factionalism. As the SDS National Council meeting convened in December 1968, National Secretary Mike Klonsky published an article in the New Left Notes (SDS' newsletter) titled "Toward A Revolutionary Youth Movement."[20] A central document in SDS' final year, Klonsky's article advocated that SDS openly align itself with the working class and begin engaging in direct action. The goal of SDS should be to build class consciousness among students by organizing working people and moving off campus, and by attacking racism, militarism and the reactionary use of state police power. The "Revolutionary Youth Movement" (RYM) proposal was aimed squarely at PL, staking out some of the party's positions as the leadership's own while denouncing PL as deviant on others. The policy provoked five days of fierce debate, even shouting matches, between SDS' national leadership and supporters of PL. But on December 31, 1968, it passed and became national SDS policy.[5][16][18][21]

Jacobs, however, felt that the RYM was insufficient. Within weeks of its adoption, he was hard at work on a new document which pushed the theoretical envelope even further.[9] Jacobs was joined by several other SDS leaders, including Rudd, Dohrn, Jeff Jones, Bill Ayers, Terry Robbins and five others.[5][15] Throughout April and May, Jacobs and the others worked on the document. They met with RYM supporters in the Northeast and Midwest, as well as with more mainstream SDSers.[5]

When the SDS National Convention opened in Chicago on June 18, 1969, Jacobs' manifesto, "You Don't Need a Weatherman to Know Which Way the Wind Blows," was published in the SDS newspaper, New Left Notes.[2][22] Although the other 10 SDS leaders had contributed to the document, Jacobs was the primary author of what came to be called the "Weatherman manifesto."[2] Robbins suggested the title, lifted from a line in the Bob Dylan song "Subterranean Homesick Blues."[2][4][5][16] Jacobs and 15 others signed it.[3][13]

The "Weatherman" statement denounced imperialism and racism,[23] and repudiated PL's claim that youth culture was bourgeois. The Weatherman manifesto also called for revolutionary violence at home to stop imperialism, and the formation of collectives in major cities to support the military struggle and stop factionalism. The Weatherman faction counted on RYM supporters to help them not only control the convention but also to pass the Weatherman manifesto. But Klonsky, Bob Avakian, and Les Coleman—all key members of the pro-RYM caucus—disagreed with many of the positions advocated in the Weatherman statement. They issued their own position paper, "Revolutionary Youth Movement II" (RYM II). Although the Weatherman and RYM II factions were opposed to PL and nearly constituted a majority of delegates, they still lost control of the convention. Leaders of the Black Panther Party made an appearance designed to attack PL supporters on the issue of racism. But when the Panthers made references to "pussy power," they and the SDS leadership were accused of male chauvinism. The next day, the Panthers accused PL of deviating from "true" Marxism–Leninism. PL leaders accused the Panthers and SDS leadership of redbaiting. Dohrn, Rudd, Jacobs, Klonsky and Robbins huddled in an attempt to strategize a way to defeat the PL faction. Dohrn took to the podium and demanded that all "true" SDSers follow her out of the convention hall. Gathering in an adjoining hall, Dohrn demanded that SDS expel all PL supporters. On June 20, the Weatherman and RYM II caucuses re-entered the main convention hall, accused the PL supporters of racism and being insufficiently opposed to imperialism, and demanded that all PL supporters be ejected. When they were not, Dohrn, Rudd, Jacobs and the other national leaders led approximately two-thirds of the delegates out of the convention hall.[5]

After the split in SDS, The Weatherman/RYM II faction began establishing collectives in cities around the country. Jacobs moved to Chicago. There, he shared an apartment with girlfriend Dohrn and Weatherman advocates Gerry Long, Jeff Blum, Bob Tomashevsky, and Peter Clapp.[5] He began traveling the country, visiting other SDS collectives to enforce the "party line," identify leaders, educate members in Marxist theory, and lecture on the need for violent action.[2]

Days of Rage

editSDS continued to fragment throughout the summer. At the United Front Against Fascism conference in Oakland, California, the Black Panthers withdrew their support of SDS when it refused to sanction community control of the police in white neighborhoods. In August, most of the RYM II supporters left the organization as well (Klonsky denounced the Weatherman manifesto for arrogance, militancy and sectarianism on August 29 in an article in New Left Notes) and began planning their own series of national mass demonstrations for October 1969. Weatherman (or the Weather Bureau, as the new organization was sometimes beginning to be called) also began planning for an October 8–11 "National Action" built around Jacobs' slogan, "bring the war home," although by now the group probably had only about 300 total members nationwide.[5] The National Action grew out of a resolution drafted by Jacobs and introduced at the October 1968 SDS National Council meeting in Boulder, Colorado. The resolution, titled "The Elections Don't Mean Shit—Vote Where the Power Is—Our Power Is In The Street" and adopted by the council, was prompted by the success of the DNC protests in August 1968 and reflected Jacobs' strong advocacy of violence as a means of achieving political goals.[9]

As part of the "National Action Staff," Jacobs was an integral part of the planning for what quickly came to be called "Four Days of Rage."[5] For Jacobs, the goal of the "Days of Rage" was clear: Weatherman would shove the war down

their dumb, fascist throats and show them, while we were at it, how much better we were than them, both tactically and strategically, as a people. In an all-out civil war over Vietnam and other fascist U.S. imperialism, we were going to bring the war home. 'Turn the imperialists' war into a civil war', in Lenin's words. And we were going to kick ass.[24]

To help start the "all-out civil war", Bill Ayers bombed a statue commemorating the policemen killed in the 1886 Haymarket Affair on the evening of October 6.[25]

But the "Days of Rage" were a failure. Jacobs told the Black Panthers there would be 25,000 protesters in Chicago for the event,[21] but no more than 200 showed up on the evening of Wednesday, October 8, 1969, in Chicago's Lincoln Park, and perhaps half of them were members of Weatherman collectives from around the country.[5] The crowd milled about for several hours, cold and uncertain. Late in the evening, Jacobs stood on the pedestal of the bombed Haymarket policemen's statue and declared: "We'll probably lose people today ... We don't really have to win here ... just the fact that we are willing to fight the police is a political victory."[26] Jacobs proceeded to compare the coming protest to the fight against fascism in World War II:

There is a war in Vietnam and we are a Vietnam within America. We are small but we have stepped in the way of history. We are going to change this country. ... The battle of Vietnam is one battle in the world revolution. It is the Stalingrad of American imperialism. We are part of that Stalingrad. We are the guerrillas fighting behind enemy lines. ... We will not commit suicide. We will not fight here. We will march to where we are within the symbol-the very pig fascist architecture. ... But we will make a political stand today.[27]

Finally, at 10:25 p.m., Jeff Jones gave the pre-arranged signal over a bullhorn, and the Weatherman action began. Jacobs, Jones, David Gilbert and others led a charge south through the city toward the Drake Hotel and the exceptionally affluent Gold Coast neighborhood, smashing windows in automobiles and buildings as they went. The mass of the crowd ran about four blocks before encountering police barricades. The mob charged the police but splintered into small groups, and more than 1,000 police counter-attacked. Although many protesters had—as J.J. did—motorcycle or football helmets on, the police were better trained and armed and nightsticks were expertly aimed to disable the rioters. Large amounts of tear gas were used, and at least twice police ran squad cars full speed into crowds. After only a half-hour or so, the riot was over: 28 policemen were injured (none seriously), six Weathermen were shot and an unknown number injured, and 68 protesters were arrested.[2][3][5][16] Jacobs was arrested almost immediately.[1]

For the next two days, Weatherman held no rallies or protests. Supporters of the RYM II movement, led by Klonsky and Noel Ignatin, held peaceful rallies of several hundred people in front of the federal courthouse, an International Harvester factory, and Cook County Hospital. The largest event of the Days of Rage occurred on Friday, October 9, when RYM II led an interracial march of 2,000 people through a Spanish-speaking part of Chicago.[2][3][16]

On Saturday, October 10, Weatherman attempted to regroup and 'reignite the revolution'. About 300 protesters marched swiftly through The Loop, Chicago's main business district, watched over by a double-line of heavily armed police. Led by Jacobs and other Weatherman members, the protesters suddenly broke through the police lines and rampaged through the Loop, smashing windows of cars and stores. But the police were ready, and quickly sealed off the protesters. Within 15 minutes, more than half the crowd had been arrested—one of the first, again, being Jacobs.[2][3][16][28]

The 'Days of Rage' cost Chicago and the state of Illinois about $183,000 ($100,000 for National Guard payroll, $35,000 in damages, and $20,000 for one injured citizen's medical expenses). Most of Weatherman and SDS' leaders were jailed, and the Weatherman bank account emptied of more than $243,000 in order to pay for bail.[5]

Going underground and the townhouse explosion

editAlthough the Days of Rage were a failure, Jacobs urged Weatherman to carry on the struggle. He urged that the Weatherman organization "go underground"—adopting secret identities, setting up safe houses, stockpiling arms and explosives, identifying strategic targets to attack, and establishing a legitimate and legal organization to speak and provide legal representation for the underground.[1][3] As the debate continued throughout the fall and early winter of 1969, Jacobs grew a pointed beard, ended his relationship with Dohrn, dated Weatherman Eleanor Raskin and dropped acid with her.[3]

From December 26 to 31, 1969, Weatherman held the last of its National Council meetings in Flint, Michigan. Flying to the event, Dohrn and Jacobs ran up and down the aisles of the airplane, seizing food, frightening the passengers.[4] The meeting, dubbed the "War Council" by the 400 people who attended, adopted Jacobs' call for violent revolution. Dohrn opened the conference by telling the delegates they needed to stop being afraid and begin the "armed struggle". Reminding the delegates of the murder of Sharon Tate and four others on August 9, 1969, by members of the Manson Family, "Dig it," Dohrn said approvingly. "First they killed those pigs, then they ate dinner in the same room with them, they even shoved a fork into a victim's stomach! Wild!"[29] She then held up three fingers in what she called the "Manson fork salute."[2][3][4][16][18] Over the next five days, the participants met in informal, random groups to discuss what "going underground" meant, how best to organize collectives, and justifications for violence.[2][3][4][16][18][30] In the evening, the groups reconvened for a mass "wargasm"—practicing karate, engaging in physical exercise, singing songs, and listening to speeches.[2][3][4][16][18] The "War Council" ended with a major speech by John Jacobs. J.J. condemned the "pacifism" of white middle-class American youth, a belief which they held because they were insulated from the violence which afflicted blacks and the poor. He predicted a successful revolution, and declared that youth were moving away from passivity and apathy and toward a new high-energy culture of "repersonalization" brought about by drugs, sex, and armed revolution.[2][3][4][16][18] "We're against everything that's 'good and decent' in honky America," Jacobs said in his most oft-quoted statement. "We will burn and loot and destroy. We are the incubation of your mother's nightmare."[31]

Two major decisions came out of the "War Council." The first was to immediately begin a violent, armed struggle against the state without attempting to organize or mobilize a broad swath of the public. The second was to create underground collectives in major cities throughout the country.[5] In fact, Weatherman created only three significant, active collectives, one in California, the Midwest, and New York City. The New York City collective was led by Jacobs and Terry Robbins, and included Ted Gold, Kathy Boudin, Cathy Wilkerson (Robbins' girlfriend), and Diana Oughton.[9] Jacobs was one of Robbins' biggest supporters, and pushed Weatherman to let Robbins be as violent as he wanted to be. The Weatherman national leadership agreed, as did the New York City collective.[32] The collective's first target was Judge John Murtagh, who was overseeing the trial of the "Panther 21".[33] On February 21, 1970, the New York City collective planted a fire-bomb outside Judge Murtagh's home. The device detonated, but did little damage.[6][21] Robbins concluded the fire-bombs were unreliable, and turned toward using dynamite.[9] The group began buying dynamite under false names from a variety of sources in the Northeast, and had soon acquired six cases of the explosive.[4]

During the week of March 2, 1970, the collective moved into a townhouse at 18 West Eleventh Street in Greenwich Village in New York City. The house belonged to James Platt Wilkerson, Cathy Wilkerson's father and a wealthy radio station owner. James Wilkerson was on vacation, and Cathy told her father she wanted to stay in the townhouse while she recovered from the flu. Reluctantly, James Wilkerson agreed.[5][9] During the first few days in the townhouse, Robbins conceived a plan to bomb an officers' dance at Fort Dix in New Jersey. Jacobs was embarrassed by Robbins' ranting about attacking a "strategic target" like a dance, but said nothing.[4] According to other members of Weatherman who spoke with the group at the time, Robbins had lost touch with reality, and the other members of the group seemed incapable of making decisions.[4][34]

On the morning of March 6, the collective began unloading several large, heavy boxes from a white station wagon and bringing them into the townhouse.[5] A few minutes before noon, an explosion in the townhouse basement tore the building apart. Two more large explosions followed, collapsing the front of the building. The ruptured gas mains below the building caught fire, consuming part of the structure. Robbins and Oughton, presumably assembling a bomb in the basement, died in the blast. Gold was trapped under falling beams and died from asphyxiation. Boudin, taking a shower at the time, fled the building naked. Wilkerson, who was dressing, ran from the rubble clad only in jeans. Anne Hoffman, wife of actor Dustin Hoffman and the Wilkersons' next-door-neighbor (the Hoffman apartment was partially damaged in the blast), grabbed a shower curtain and covered Boudin with it. Susan Wager, ex-wife of actor Henry Fonda, rushed up the street and helped the two women to her home. Wager gave them both some clothes, but the two women fled. Jacobs was not in the townhouse at the time, and went into hiding after the blast.[2][4][16]

Initially, the townhouse explosion appeared to have little effect on Jacobs. He continued to press for armed revolution, and even advocated that Weatherman establish roving bands of armed radicals to help start the revolution.[16]

On April 2, 1970, Attorney General John N. Mitchell personally announced federal indictments against 11 members of Weatherman for their role in the Days of Rage. Included in the indictments was John Jacobs, who was accused of crossing state lines with intent to riot.[35]

But other leaders in Weatherman began to reconsider armed struggle as a tactic. Dohrn called for a meeting in late April 1970 of all of Weatherman's top leadership at the collective safe house in Mendocino, California, north of San Francisco. Exhausted from months on the run, consumed by fear, and depressed by the deaths of Robbins, Oughton and Gold, the leadership agreed to lay some ground rules for the Mendocino debates. There would be no shouting, and no discussion of theory or philosophy in the evenings. Jacobs vehemently disagreed, and was largely excluded from the ensuing discussions. Over the next several days, the leaders of the Weather Underground discussed how to respond to the townhouse blast. After several days, the group concluded that Jacobs and Robbins had committed "the military error" by advocating armed revolution. As leader of the group, Dohrn had the power to expel Jacobs. She did so, and Jacobs left quietly. He never participated in radical activities again.[2][3][4]

The Weatherman organization did not, however, immediately announce its decision. As early as May 21, 1970, it issued a communiqué announcing its continuing support for armed revolution in the United States.[4] Several more communiqués followed throughout the year, as more Weatherman-sponsored bombings occurred across the country. It was not until December 6, 1970, that the group would condemn Jacobs' "military error." The renunciation of violence came in a statement titled "New Morning-Changing Weather." In that document, Dohrn called the townhouse blast "the military error" and renamed the organization a less-sexist "Weather Underground."[4]

Life on the run and death

editJohn Jacobs spent the last 27 years of his life on the run. Although he had argued for rising violence in the aftermath of the townhouse explosion, Jacobs secretly felt intense guilt for having caused (as he saw it) the deaths of Robbins, Gold and Oughton.[1] He also felt he was made the scapegoat for the townhouse explosion. "I know that for myself, part of what I wanted from the political movement was friends, family and community," he wrote. "Somehow I thought that among people who were working together for social change, the values of the better society they were fighting for would be manifest in better social relations among themselves ...[1] He later wrote that he had "lost, killed, alienated or driven away" all his friends, and that—fugitive or not—his life was "sad and lonely".[4]

Jacobs wandered in northern California and Mexico for several years under several aliases,[1] taking drugs and drinking heavily. He was almost captured once in California, but escaped by climbing out a window and escaping across a roof.[1] Jacobs traveled to Canada, where his older brother was attending Simon Fraser University. The two did not meet often, in part because they looked alike but also because the FBI and Royal Canadian Mounted Police were still watching Robert in the hopes JJ would visit him.[1] Jacobs first settled on Vancouver Island, British Columbia, and worked at planting trees—donating most of his money to the building of a Buddhist temple on nearby Saltspring Island.[1]

Jacobs soon moved to the mainland and settled in the city of Vancouver,[4] where he took the name "Wayne Curry."[1] He met his first life partner there, and he and the woman had two children by 1977. The relationship ended in the early 1980s, and Jacobs lived alone for several years.[1] He continued to harbor a bitter hatred of police,[26] and began taking cocaine.[1] In 1986, Jacobs met and began living with Marion MacPherson. Jacobs worked at various blue-collar jobs, including stonecutter and construction worker, and made extra money selling marijuana. The couple became common law husband and wife, and raised four children (some from MacPherson's prior marriage).[1]

Jacobs took courses in Third World politics and history at several local colleges and universities, receiving grades of A's and B's.[1] He spent much of his free time gardening or reading, and although acquaintances unwittingly urged him to become involved in political activity he refused.[1] He spent much of his time in his basement, reading newspapers and clipping articles (especially those which told of his former Weatherman comrades resurfacing and reintegrating back into society).[1]

The U.S. Department of Justice dropped its federal warrant against Jacobs in October 1979.[36]

In 1996, Jacobs was diagnosed with melanoma. The cancer soon spread to his brain, lungs, and lymph nodes, and his skin became painfully sensitive to the slightest touch.[1]

John Jacobs died on October 20, 1997, of complications related to melanoma. He fell ill on October 19, and police and medical personnel were called to his home by his wife. When police officers inadvertently touched his sensitive skin (despite his wife's caution not to), he became violent and beat several officers before being subdued. Jacobs died the next day.[1]

Jacobs was cremated. Some of his ashes were spread in his backyard, some in English Bay, and some in Oregon (near a place he had visited while on the run).[1] Some of his ashes were also taken to Cuba and spread near the mausoleum of Che Guevara. A photo of Jacobs from the late 1960s is attached to a plaque next to the site.[1] An extensive statement, documenting Jacobs' life, is written on the plaque. It ends with the statement: "He wanted to live like Che. Let him rest with Che."[1]

In popular culture

editInterview footage of John Jacobs was included in the 2002 film The Weather Underground.[37]

In the fiction novel American Pastoral by Philip Roth, the daughter of the central character appears to be a member of the Weather Underground. The novel incorporates Jacobs' "We're against everything that's 'good and decent' ..." statement at the 1969 "War Council" in Flint.

Notes

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac Gillies, Kevin (November 1, 1998). "The Last Radical". columbia.edu. Vancouver Magazine. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Jacobs, The Way the Wind Blew: A History of the Weather Underground, 1997.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Jones, A Radical Line: From the Labor Movement to the Weather Underground, One Family's Century of Conscience, 2004.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Varon, Bringing the War Home: The Weather Underground, the Red Army Faction, and Revolutionary Violence in the Sixties and Seventies, 2004.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Sale, SDS, 1973.

- ^ a b c d Cannato, The Ungovernable City: John Lindsay and His Struggle to Save New York, 2001.

- ^ McCaughey, Stand, Columbia: A History of Columbia University, 2003.

- ^ Rudd, "Columbia," Movement, March 1969.

- ^ a b c d e f g Wilkerson, Flying Close to the Sun: My Life and Times As a Weatherman, 2007.

- ^ Castellucci, John. "The Night They Burned Ranum's Papers", Chronicle of Higher Education. February 14, 2010. Accessed September 17, 2011.

- ^ Matusow, The Unraveling of America: A History of Liberalism in the 1960s, 1984.

- ^ Avorn, Up Against the Ivy Wall, 1968; Kahn, The Battle for Morningside Heights: Why Students Rebel, 1970; Collier and Horowitz, "Doing It: The Inside Story of the Rise and Fall of the Weather Underground," Rolling Stone, September 30, 1982.

- ^ a b Rudd, "Organizing vs. Activism in 1968," speech given at Drew University, November 4, 2006.

- ^ The chant began at Columbia during the protests, and was modeled on Che Guevara's slogan of "two, three, many Vietnams." See: Sale, SDS, 1973.

- ^ a b Allyn, Make Love, Not War: The Sexual Revolution: An Unfettered History, 2000.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Berger, Outlaws of America: The Weather Underground And the Politics of Solidarity, 2006.

- ^ Varon, "Between Revolution 9 and Thesis 11: Or, Will We Learn (Again) to Start Worrying and Change the World?", in The New Left Revisited: Critical Perspectives on the Past, 2002.

- ^ a b c d e f Elbaum, Revolution in the Air: Sixties Radicals Turn to Lenin, Mao and Che, 2002.

- ^ Alexander, Maoism in the Developed World, 2001; Sprinzak, "The Student Movement: Marxism as Symbolic Action," in Varieties of Marxism, 1977.

- ^ Klonsky, "Toward A Revolutionary Youth Movement," New Left Notes, December 23, 1968.

- ^ a b c Barber, "Leading the Vanguard: White New Leftists School the Panthers on Black Revolution," in In Search of the Black Panther Party: New Perspectives on a Revolutionary Movement, 2006.

- ^ "You Don't Need A Weatherman to Know Which Way the Wind Blows," New Left Notes, June 18, 1969.

- ^ PL had argued that nationalist wars of independence were deviations from the struggle against capitalism, and that attacks on racism distracted the movement from focusing on workers. See: Sale, SDS, 1973.

- ^ Quoted in Gillies, "The Last Radical," Vancouver Magazine, November 1998.

- ^ Avrich, The Haymarket Tragedy, 1984; Ayers, Fugitive Days: A Memoir, 2001; Shepard, "Antiwar Movements, Then and Now," Monthly Review, February 2002; "Statue Honoring Police Is Blown Up in Chicago," New York Times, October 8, 1969; "Haymarket Statue Bombed," Chicago Tribune, October 7, 1969.

- ^ a b Smith, "Sudden Impact," Chicago Magazine, December 2006.

- ^ Quoted in Short, "The Weathermen're Shot, They're Bleeding, They're Running, They're Wiping Stuff Out," Harvard Crimson, June 11, 1970.

- ^ Mestrovic, "For Eastern Europe: PR or Policy?", Commonweal, October 1969.

- ^ Quoted in Varon, Bringing the War Home: The Weather Underground, the Red Army Faction, and Revolutionary Violence in the Sixties and Seventies, 2004.

- ^ One small group concluded that all Caucasians were irredeemably corrupted by capitalism and imperialism. Therefore, killing infants constituted revolutionary action. One evening, a participant who favored killing white babies shouted, "All white babies are pigs!" See: Sale, SDS, 1973, p. 337.

- ^ Quoted in Varon, Bringing the War Home: The Weather Underground, the Red Army Faction, and Revolutionary Violence in the Sixties and Seventies, 2004, p. 160.

- ^ Good, "Brian Flanagan Speaks," Next Left Notes, 2005.

- ^ Twenty-one members of the Black Panthers—nearly all of them Panther leaders in the Northeast—had been indicted in April 1969 and charged with conspiracy to kill police officers and bomb police stations, department stores, and the Bronx Botanical Gardens. Held on excessively high bail, the case against them was notoriously weak and charges against three defendants were dropped before trial. The "Panther 21" became a cause célèbre in radical circles. All members of the "Panther 21" were found not-guilty on April 22, 1971. See: Kempton, The Briar Patch: The Trial of the Panther 21, 1997; Austin, Up Against the Wall: Violence in the Making and Unmaking of the Black Panther Party, 2006; Joseph, Waiting 'Til the Midnight Hour: A Narrative History of Black Power in America, 2006.

- ^ Dohrn, Ayers and Jones, Sing a Battle Song: The Revolutionary Poetry, Statements, and Communiqués of the Weather Underground, 1970-1974, 2006.

- ^ Kifner, "12 S.D.S. Militants Indicted in Chicago," New York Times, April 3, 1970; Churchill and Vander Wall, The COINTELPRO Papers: Documents from the FBI's Secret Wars Against Dissent in the United States, 2002.

- ^ "FBI Drops 10-Year Hunt for 'Weather' Group Leaders," Los Angeles Times, October 20, 1979.

- ^ MacLennan, "How Can You Do Nothing? The Weather Underground Bring the War Home," The Lamp, April 2004; Patterson, "They Emerged From 1960s Radical Chic to Become America's Most Wanted Fugitives," The Guardian, July 4, 2003.

References

edit- Alexander, Robert J. Maoism in the Developed World. New York: Praeger Publishers, 2001. ISBN 0-275-96148-6

- Allyn, David. Make Love, Not War: The Sexual Revolution: An Unfettered History. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2000. ISBN 0-316-03930-6

- Avorn, J.L. Up Against the Ivy Wall. New York: Scribner, 1968. ISBN 0-689-70236-1

- Austin, Curtis J. Up Against the Wall: Violence in the Making and Unmaking of the Black Panther Party. Little Rock: University of Arkansas Press, 2006. ISBN 1-55728-827-5

- Avrich, Paul. The Haymarket Tragedy. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1984. ISBN 0-691-00600-8

- Ayers, William. Fugitive Days: A Memoir. Boston: Beacon Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8070-7124-2

- Barber, David. "Leading the Vanguard: White New Leftists School the Panthers on Black Revolution." In In Search of the Black Panther Party: New Perspectives on a Revolutionary Movement. New ed. Jama Lazerow and Yohuru Williams, eds. Raleigh, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2006. ISBN 0-8223-3890-4

- Berger, Dan. Outlaws of America: The Weather Underground and the Politics of Solidarity. Paperback ed. Oakland, Calif.: AK Press, 2006. ISBN 1-904859-41-0

- Burns, Vincent and Peterson, Kate Dempsey. Terrorism: A Documentary and Reference Guide. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2005. ISBN 0-313-33213-4

- Cannato, Vincent. The Ungovernable City: John Lindsay and His Struggle to Save New York. New York: Basic Books, 2001. ISBN 0-465-00843-7

- Churchill, Ward and Vander Wall, Jim. The COINTELPRO Papers: Documents from the FBI's Secret Wars Against Dissent in the United States. 2d ed. Boston: South End Press, 2002. ISBN 0-89608-648-8

- Collier, Peter, and Horowitz, David. "Doing It: The Inside Story of the Rise and Fall of the Weather Underground." Rolling Stone. September 30, 1982.

- Dohrn, Bernardine; Ayers, Bill; and Jones, Jeff, eds. Sing a Battle Song: The Revolutionary Poetry, Statements, and Communiqués of the Weather Underground, 1970-1974. New York: Seven Stories Press, 2006. ISBN 1-58322-726-1

- Elbaum, Max. Revolution in the Air: Sixties Radicals Turn to Lenin, Mao and Che. New York: Verso, 2002. ISBN 1-85984-617-3

- "FBI Drops 10-Year Hunt for 'Weather' Group Leaders." Los Angeles Times. October 20, 1979.

- Gillies, Kevin. "The Last Radical." Vancouver Magazine. November 1998.

- Good, Thomas. "Brian Flanagan Speaks." Next Left Notes. 2005.

- "Haymarket Statue Bombed." Chicago Tribune. October 7, 1969.

- Jacobs, Ron. The Way the Wind Blew: A History of the Weather Underground. Paperback ed. New York: Verso, 1997. ISBN 1-85984-167-8

- Jones, Thai. A Radical Line: From the Labor Movement to the Weather Underground, One Family's Century of Conscience. New York: The Free Press, 2004. ISBN 0-7432-5027-3

- Joseph, Peniel E. Waiting 'Til the Midnight Hour: A Narrative History of Black Power in America. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2006. ISBN 0-8050-7539-9

- Kahn, Roger. The Battle for Morningside Heights: Why Students Rebel. New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1970. ISBN 0-688-29254-2

- Kempton, Murray. The Briar Patch: The Trial of the Panther 21. Paperback reprint ed. New York: Da Capo Press, 1997. ISBN 0-306-80799-8

- Kifner, John. "12 S.D.S. Militants Indicted in Chicago." New York Times. April 3, 1970.

- Klonsky, Mike. "Toward A Revolutionary Youth Movement." New Left Notes. December 23, 1968.

- MacLennan, Catherine. "How Can You Do Nothing? The Weather Underground Bring the War Home." The Lamp. April 2004.

- Matusow, Allen J. The Unraveling of America: A History of Liberalism in the 1960s. New York: Harper & Row, 1984. ISBN 0-06-015224-9

- McCaughey, Robert. Stand, Columbia: A History of Columbia University. New York: Columbia University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-231-13008-2

- Mestrovic, Matthew M. "For Eastern Europe: PR or Policy?" Commonweal. October 1969.

- Patterson, John. "They Emerged From 1960s Radical Chic to Become America's Most Wanted Fugitives." The Guardian. July 4, 2003.

- Rudd, Mark. "Columbia." Movement. March 1969.

- Rudd, Mark. "Organizing vs. Activism in 1968." Speech given at Drew University, November 4, 2006. Transcribed by Brian Kelly, January 9, 2008.

- Sale, Kirkpatrick. SDS. New York: Random House, 1973. ISBN 0-394-47889-4

- Shepard, Benjamin. "Antiwar Movements, Then and Now." Monthly Review. February 2002.

- Short, John G. "The Weathermen're Shot, They're Bleeding, They're Running, They're Wiping Stuff Out." Harvard Crimson. June 11, 1970.

- Smith, Bryan. "Sudden Impact." Chicago Magazine. December 2006.

- Sprinzak, Ehud. "The Student Movement: Marxism as Symbolic Action." In Varieties of Marxism. Shlomo Avineri, ed. New York: Springer, 1977. ISBN 90-247-2024-9

- "Statue Honoring Police Is Blown Up in Chicago." New York Times. October 8, 1969.

- Varon, Jeremy. Bringing the War Home: The Weather Underground, the Red Army Faction, and Revolutionary Violence in the Sixties and Seventies. Paperback ed. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press, 2004. ISBN 0-520-24119-3

- Varon, Jeremy. "Between Revolution 9 and Thesis 11: Or, Will We Learn (Again) to Start Worrying and Change the World?" In The New Left Revisited: Critical Perspectives on the Past. John McMillian and Paul Buhle, eds. Philadelphia, Pa.: Temple University Press, 2002. ISBN 1-56639-976-9

- Wilkerson, Cathy. Flying Close to the Sun: My Life and Times As a Weatherman. New York: Seven Stories Press, 2007. ISBN 1-58322-771-7

- "You Don't Need A Weatherman to Know Which Way the Wind Blows." New Left Notes. June 18, 1969.

External links

edit- "You Don't Need A Weatherman To Know Which Way The Wind Blows." New Left Notes. June 18, 1969. (Complete text of the founding document of Weatherman, by John Jacobs)