A synovial joint, also known as diarthrosis, join bones or cartilage with a fibrous joint capsule that is continuous with the periosteum of the joined bones, constitutes the outer boundary of a synovial cavity, and surrounds the bones' articulating surfaces. This joint unites long bones and permits free bone movement and greater mobility.[1] The synovial cavity/joint is filled with synovial fluid. The joint capsule is made up of an outer layer of fibrous membrane, which keeps the bones together structurally, and an inner layer, the synovial membrane, which seals in the synovial fluid.

| Synovial joint | |

|---|---|

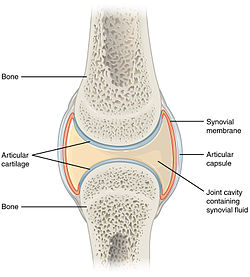

Structure of synovial joint | |

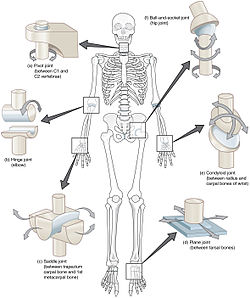

Types of synovial joints.

Clockwise from top-right: ball and socket joint, condyloid joint, plane joint, saddle joint, hinge joint and pivot joint. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | junctura synovialis |

| TA98 | A03.0.00.020 |

| TA2 | 1533 |

| FMA | 7501 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

They are the most common and most movable type of joint in the body of a mammal. As with most other joints, synovial joints achieve movement at the point of contact of the articulating bones.

Structure

editSynovial joints contain the following structures:

- Synovial cavity: all diarthroses have the characteristic space between the bones that is filled with synovial fluid.

- Joint capsule: the fibrous capsule, continuous with the periosteum of articulating bones, surrounds the diarthrosis and unites the articulating bones; the joint capsule consists of two layers - (1) the outer fibrous membrane that may contain ligaments and (2) the inner synovial membrane that secretes the lubricating, shock absorbing, and joint-nourishing synovial fluid; the joint capsule is highly innervated, but without blood and lymph vessels, and receives nutrition from the surrounding blood supply via either diffusion (slow), or via convection (fast, more efficient), induced through exercise.

- Articular cartilage: the bones of a synovial joint are covered by a layer of hyaline cartilage that lines the epiphyses of the joint end of the bone with a smooth, slippery surface that prevents adhesion; articular cartilage functions to absorb shock and reduce friction during movement.

Many, but not all, synovial joints also contain additional structures:[2]

- Articular discs or menisci - the fibrocartilage pads between opposing surfaces in a joint

- Articular fat pads - adipose tissue pads that protect the articular cartilage, as seen in the infrapatellar fat pad in the knee

- Tendons[2] - cords of dense regular connective tissue composed of parallel bundles of collagen fibers

- Accessory ligaments (extracapsular and intracapsular) - the fibers of some fibrous membranes are arranged in parallel bundles of dense regular connective tissue that are highly adapted for resisting strains to prevent extreme movements that may damage the articulation[citation needed]

- Bursae - sac-like structures that are situated strategically to alleviate friction in some joints (shoulder and knee) that are filled with fluid similar to synovial fluid[3][page needed]

The bone surrounding the joint on the proximal side is sometimes called the plafond (French word for ceiling), especially in the talocrural joint. Damage to this structure is referred to as a Gosselin fracture.

Blood supply

editThe blood supply of a synovial joint is derived from the arteries sharing in the anastomosis around the joint.

Types

editThere are seven types of synovial joints.[4] Some are relatively immobile, therefore more stable. Others have multiple degrees of freedom, but at the expense of greater risk of injury.[4] In ascending order of mobility, they are:

| Name | Example | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Plane joints (or gliding joint) |

carpals of the wrist, acromioclavicular joint | These joints allow only gliding or sliding movements, are multi-axial such as the articulation between vertebrae. |

| Hinge joints | elbow (between the humerus and the ulna) | These joints act as a door hinge does, allowing flexion and extension in just one plane, i.e. uniaxial. |

| Pivot joints | atlanto-axial joint, proximal radioulnar joint, and distal radioulnar joint | One bone rotates about another |

| Condyloid joints (or ellipsoidal joints) |

wrist joint (radiocarpal joint) | A condyloid joint is a modified ball and socket joint that allows primary movement within two perpendicular axes, passive or secondary movement may occur on a third axes. Some classifications make a distinction between condyloid and ellipsoid joints;[5][6] these joints allow flexion, extension, abduction, and adduction movements (circumduction). |

| Saddle joints | Carpometacarpal or trapeziometacarpal joint of thumb (between the metacarpal and carpal - trapezium), sternoclavicular joint | Saddle joints, where the two surfaces are reciprocally concave/convex in shape, which resemble a saddle, permit the same movements as the condyloid joints but allows greater movement. |

| Ball and socket joints "universal Joint" |

shoulder (glenohumeral) and hip joints | These allow for all movements except gliding |

| Compound joints[7][8] / bicondyloid joints[2] |

knee joint | condylar joint (condyles of femur join with condyles of tibia) and saddle joint (lower end of femur joins with patella) |

Multiaxial joints

editA multiaxial joint (polyaxial joint or triaxial joint) is a synovial joint that allows for several directions of movement.[9] In the human body, the shoulder and hip joints are multiaxial joints.[10] They allow the upper or lower limb to move in an anterior-posterior direction and a medial-lateral direction. In addition, the limb can also be rotated around its long axis. This third movement results in rotation of the limb so that its anterior surface is moved either toward or away from the midline of the body.[11]

Function

editThe movements possible with synovial joints are:

Clinical significance

editThe joint space equals the distance between the involved bones of the joint. A joint space narrowing is a sign of either (or both) osteoarthritis and inflammatory degeneration.[12] The normal joint space is at least 2 mm in the hip (at the superior acetabulum),[13] at least 3 mm in the knee,[14] and 4–5 mm in the shoulder joint.[15] For the temporomandibular joint, a joint space of between 1.5 and 4 mm is regarded as normal.[16] Joint space narrowing is therefore a component of several radiographic classifications of osteoarthritis.

In rheumatoid arthritis, the clinical manifestations are primarily synovial inflammation and joint damage. The fibroblast-like synoviocytes, highly specialized mesenchymal cells found in the synovial membrane, have an active and prominent role in the pathogenic processes in the rheumatic joints.[17] Therapies that target these cells are emerging as promising therapeutic tools, raising hope for future applications in rheumatoid arthritis.[17]

References

edit- ^ The Musculoskeletal System. In: Dutton M. eds. Dutton's Orthopaedic Examination, Evaluation, and Intervention, 5e. McGraw-Hill; Accessed January 25, 2021. https://accessphysiotherapy-mhmedical-com.libaccess.lib.mcmaster.ca/content.aspx?bookid=2707§ionid=224662311

- ^ a b c Drake, Richard L.; Vogl, Wayne; Mitchell, Adam W. M.; Gray, Henry (2015). "Skeletal system". Gray's Anatomy for Students (3rd ed.). p. 20. ISBN 978-0-7020-5131-9. OCLC 881508489.

- ^ Tortora & Derrickson () Principles of Anatomy & Physiology (12th ed.). Wiley & Sons

- ^ a b Umich (2010). "Introduction to Joints". Learning Modules - Medical Gross Anatomy. University of Michigan Medical School. Archived from the original on 2011-11-22.

- ^ Rogers, Kara (2010) Bone and Muscle: Structure, Force, and Motion p.157

- ^ Sharkey, John (2008) The Concise Book of Neuromuscular Therapy p.33

- ^ Moini (2011) Introduction to Pathology for the Physical Therapist Assistant pp.231-2

- ^ Bruce Abernethy (2005) The Biophysical Foundations Of Human Movement pp.23, 331

- ^ Miles, Linda. "LibGuides: BIO 140 - Human Biology I - Textbook: Chapter 41 - Classification of Joints". guides.hostos.cuny.edu. Hostos Community College Library. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ Lawry, George V. (1 January 2006). "Chapter 1 - Anatomy of Joints, General Considerations, and Principles of Joint Examination". Musculoskeletal Examination and Joint Injection Techniques. Mosby. pp. 1–6. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ Betts, J. Gordon (2013). "9.1 Classification of joints". Anatomy & physiology. Houston, Texas: OpenStax. ISBN 978-1-947172-04-3. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- ^ Jacobson, Jon A.; Girish, Gandikota; Jiang, Yebin; Sabb, Brian J. (2008). "Radiographic Evaluation of Arthritis: Degenerative Joint Disease and Variations". Radiology. 248 (3): 737–747. doi:10.1148/radiol.2483062112. ISSN 0033-8419. PMID 18710973.

- ^ Lequesne, M (2004). "The normal hip joint space: variations in width, shape, and architecture on 223 pelvic radiographs". Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 63 (9): 1145–1151. doi:10.1136/ard.2003.018424. ISSN 0003-4967. PMC 1755132. PMID 15308525.

- ^ Roland W. Moskowitz (2007). Osteoarthritis: Diagnosis and Medical/surgical Management, LWW Doody's all reviewed collection. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 6. ISBN 9780781767071.

- ^ "Glenohumeral joint space". radref.org., in turn citing: Petersson, Claes J.; Redlund-Johnell, Inga (2009). "Joint Space in Normal Gleno-Humeral Radiographs". Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica. 54 (2): 274–276. doi:10.3109/17453678308996569. ISSN 0001-6470. PMID 6846006.

- ^ Massilla Mani, F.; Sivasubramanian, S. Satha (2016). "A study of temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis using computed tomographic imaging". Biomedical Journal. 39 (3): 201–206. doi:10.1016/j.bj.2016.06.003. ISSN 2319-4170. PMC 6138784. PMID 27621122.

- ^ a b Nygaard, Gyrid; Firestein, Gary S. (2020). "Restoring synovial homeostasis in rheumatoid arthritis by targeting fibroblast-like synoviocytes". Nature Reviews Rheumatology. 16 (6): 316–333. doi:10.1038/s41584-020-0413-5. PMC 7987137. PMID 32393826.

Sources

editThis article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY 4.0. Text taken from Anatomy and Physiology, J. Gordon Betts et al, Openstax.