Antonio José Martínez (January 17, 1793[1] – July 27, 1867[2]) was a New Mexican priest, educator, publisher, rancher, farmer, community leader, and politician. He lived through and influenced three distinct periods of New Mexico's history: the Spanish period, the Mexican period, and the American occupation and subsequent territorial period. Martínez appears as a character in Willa Cather's novel, Death Comes for the Archbishop.

Antonio José Martínez | |

|---|---|

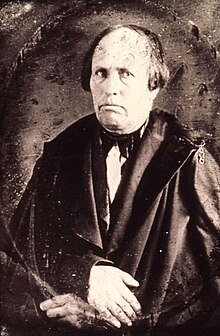

Padre Martínez, c. 1848 | |

| Born | January 17, 1793 |

| Died | July 27, 1867 (aged 74) |

| Nationality | Spanish (until 1821) Mexican (1821-1848) American (after 1848) |

| Occupation(s) | Priest, educator, publisher, rancher, farmer, community leader, and politician |

Spanish period

editMartínez was born Antonio Jose Martinez in Abiquiu on January 17, 1793, when New Mexico was a very isolated and desolate territory of the Spanish Empire. In 1804, the Martinez family, including his father Severino and five siblings, moved to Taos, a prosperous outpost, where they came to be known as Martínez.[3] His mother was María del Carmel Santistévan of La Plaza de Santa Rosa de Abiquiú.[4] During his upbringing, Martínez's father taught him the importance of ranching and farming at the Hacienda Martínez in Northern New Mexico. In 1811, Martínez married María de la Luz, who died giving birth to their daughter less than a year later, when he was 19.[5] Their child was named in honor of María de la Luz. Six years later Martínez moved south after much thought and correspondence with the Bishop of Durango. He decided to travel there in 1817, and become a priest, enrolling in the Tridentine Seminary of the Diocese of Durango.[5] Martínez not only excelled at the seminary but also in understanding the ideals of liberal Mexican politicians and teachers of his day, including Miguel Hidalgo. After six years, Martínez was ordained, and he returned to New Mexico, where after a few years in other parishes, he became the parish priest of Taos, and from then on was known as Padre Martínez.[5]

American period

editIn 1841, the newly formed Republic of Texas recognized the difficulties New Mexico was facing and decided to take advantage of them by sending an expedition to invade New Mexico and possibly annex the territory. The invasion failed, and the Texans were captured by Manuel Armijo. This event, in addition to the numerous Americans already living in New Mexico, led many to believe that New Mexico had weakened and become ready for invasion. The Mexican–American War began in 1846. Stephen W. Kearny led 1,700 American troops into Santa Fe without encountering any resistance. Before the invasion, Martínez had witnessed the animosity towards Native Americans and Mexicans displayed by the Anglos living in New Mexico. He encouraged his students to study law and it was to them he delivered his famous quote, "The American government resembles a burro; but on this burro lawyers will ride, not priests."[6]

Within a year of the American occupation, the Taos Revolt occurred. Charles Bent, the newly appointed American governor of New Mexico, was assassinated in the uprising. American forces quickly regained power, instituted martial law, and executed the rebels involved. Many, including Kit Carson, believed Martínez himself took part in some way in instigating the rebellion, but nothing has been proven. In a letter to a friend in Santa Fe, Martínez stated that the American reprisals were too harsh and would hinder future relations between New Mexico and its new rulers. Despite the problems, Martínez was able to adjust to the administration and for seven years played a dominant role in the conventions and legislative sessions of the new Territory.

Bishop Lamy

editWith the new government came new leadership, both political and religious. Jean Baptiste Lamy, a Frenchman nearly 21 years younger than Martínez, became the vicar apostolic of Santa Fe in 1851. Martínez supported Lamy until January 1854 when Lamy issued a letter instituting mandatory tithing and decreeing that heads of families that failed to tithe be denied the sacraments. Martínez publicly protested the letter and openly contested it in the secular press. From then on, Lamy and Martínez clashed over many issues, such as the effects of frontier life on Catholic standards, and women's issues. The two also argued over interpretations of canon law. The situation culminated when Lamy wrote a letter explaining that he felt New Mexicans faced a sad future because they didn't have the intellectual liveliness of Americans and their morals were primitive. These comments outraged New Mexicans. The clergy of New Mexico wrote a letter directly to the Pope, expressing their concern about Lamy. Martínez was not involved in the letter but continued to write communiques criticizing Lamy for the Santa Fe Gazette.

In early 1856, Martínez offered his conditional resignation, but admitted his parishioners in Taos, New Mexico to his private chapel in his home and ministered to them from there. On October 27, 1856, Lamy suspended Martínez. In response, Martínez antagonized the pastor that Lamy sent in his place, persuaded a neighboring priest of his goals and gained the allegiance of approximately a third of the parishioners in the two parishes. Finally, in April 1858, Lamy excommunicated Martínez. Martínez never recognized the validity of the excommunication, and continued to minister to his supporters until his death. Martínez also continued to write about Christianity, publishing his famous work, Religión, in which he called for small honoraria for priests in New Mexico, because of the heavy demands associated with New Mexico's isolation. He also explained the problem of denying sacraments to individuals because of their financial status. Lastly, he condemned the Spanish Inquisition and all the actions associated with it, including the many excommunications.

Death and legacy

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2020) |

Father Antonio José Martínez died on July 27, 1867. Infirm and aged beyond his years, Martínez lived the last ten years of his life estranged from Bishop Jean Baptiste Lamy. By the spring of 1858, Bishop Lamy felt compelled to excommunicate Martínez not for moral failings, but for his "scandalous writings."[citation needed] Bishop Lamy wrote his denunciation of Martínez in the marginal notes of the Baptism and Funeral Register of Our Lady of Guadalupe Church where he had served since 1826. The writings in La Gaceta of Santa Fe were a critique of the Bishop's re-introduction of the system of tithing that Martínez since 1829 successfully advocated the government revoke.

In 1826, he established a coed elementary school; in 1833 a seminary from which 16 men were ordained to the priesthood; and in 1846 a law school that graduated many of the earliest lawyers and politicians of the Territory of New Mexico.

He produced a speller for the children of his family members, and later obtained the first printing press in New Mexico. In 1838, he published his autobiography on his press, and the following year published the first book printed in New Mexico, a bilingual ritual—Latin and Spanish. He published only six issues of the newspaper called El Crepúsculo de Libertad; published religious/devotional tracts and texts for his elementary school, seminary, and law school.

Martínez was a licensed attorney turned politician, and served five times under the Republic of Mexico on the legislature of the Departamento de Nuevo Mexico, and six times for the Territory of New Mexico under the United States.[citation needed]

He was married before he became a priest; his wife died in childbirth, and his daughter died at the young age of 12. Even after ordination, Martínez had other children that he recognized as heirs in his Last Will and Testament. His eldest was Santiago Valdez (b. 1830) who wrote his 1877 biography, and the second to the youngest was Vicente Ferrer Romero (b. 1844) who became an effective evangelizer for the Presbyterian Church.

Martínez has been accused of instigating the Chimayó Rebellion of 1837 and the Taos Revolt of 1847 with its concomitant assassination of Governor Charles Bent, but this is unlikely.[7]

After his tension and controversies with Bishop Lamy, in 1863 it seems he flirted with becoming an Anglican, observing the Holy Communion "according to the reformed rite" with Bishop Talbot.[8] However, he remained staunchly Roman Catholic as his Last Will and Testament testifies.[citation needed]

In his Last Will, Martínez expressed a desire not to have a public ceremony, nevertheless there was a large funeral ceremony for him. Martínez requested to be buried in his Oratorio, dedicated to La Purísima Concepción, contiguous to and on the west-side of his residence. This request was honored, and so he was buried in his own Oratorio that he had built on his property. A quarter century later in 1891, his body was moved about two miles east the American Cemetery. The land, originally owned by Martínez, was deeded to Theodora Romero, and then came into possession of the Kit Carson park and cemetery in Taos.

Inscribed on the Martínez tombstone are the words La Honra de su País ("The Honor of his Homeland"). Martínez's peers in the Territorial Legislature pronounced this encomium in 1867, the year of his death. Sculptor Huberto Maestas of San Luis, Colorado sculpted the larger than life-sized bronze memorial of Martínez unveiled at Taos Plaza on July 16, 2006.

Controversy

editRevolution of 1837

editWhen Santa Anna became the President of Mexico in 1833, he intentionally began to centralize and departmentalize the Mexican government. Santa Anna also began to impose harsher taxes in New Mexico, which sparked a rebellion in the northern part of the province. In 1837, the rebels, mostly poorer ranchers and farmers, captured Santa Fe, killed governor Albino Pérez, and installed their own governor, José María González. The leaders of the rebellion were divided on their goals and soon factionalized.

American merchants and traders within New Mexico were uncomfortable about the new government and funded a Mexican army led by Manuel Armijo to put down the uprising. The Martínez family had grown wealthy through trade and would have become a critical subject had the rebellion survived. Martínez not only helped fund the Mexican army, but also offered his services to Armijo as chaplain of the army until the termination of the revolt in early 1838, when the old administration was restored with Armijo as governor. Upon suppression of the rebellion, Armijo ordered the execution of José Gonzales, but not before directing Martínez: "Padre Martĺnez, confiese á este genĺzaro para que le dén cinco balazos" ("Father Martĺnez, hear this genizaro's confession so that he may be shot five times").[9] Martínez heard Gonzales's confession and then handed him over to Armijo.[citation needed]

Penitentes

editFollowing Mexican independence from Spain, Church authorities in Mexico withdrew the Franciscan, Dominican and Jesuit missionaries from its provinces. In 1832, the last of the Franciscan regional authorities authorized Padre Martínez to supervise the Penitente brotherhood, a type of folk Catholicism that had developed among the Hispano New Mexicans. In addition to offering spiritual and social aid to the community, the Penitentes engaged in such ascetic practices as flagellation and the carrying of heavy crosses. Bishop Lamy unsuccessfully attempted to suppress the brotherhood as a part of the "Americanization" of the Church in New Mexico. Padre Martínez championed the Penitente cause, putting him squarely at odds with Lamy.

Quotes

editHis greate name deserves to be written in letters of gold in all high places that this gaping and ignorant multitude might fall down and worship it, that he has and done condisend to remain amongst and instrkut such a people.

— Thoughts on Padre Martínez and the people of New Mexico in a letter by Charles Bent[10]

Charles Bent's statement about the "greate literary Martinez" and similar comments are sarcastic. Bent felt a strong antipathy toward Padre Antonio José Martínez who opposed his ambition to acquire the Guadalupe-Miranda (Beaubien) Land Grant / Maxwell Land Grant. Padre Martinez insisted that the extremely large territory, over 1.7 million acres including what is today Philmont Scout Ranch, remain common grazing grounds the inhabitants of New Mexico since time immemorial used for their cattle.

In the early 1830s Charles Bent, together with his brother William, founded a fort on the Arkansas River (the Spanish called it Rio Napiste) in what is today's southern Colorado. The river marked the southern boundary between the United States of America and the Kingdom of Spain since the Otis-Anin Treaty of 1819. A couple of years later—after Mexico's independence from Spain in 1821—the river became the northern boundary of the Republic of Mexico with the United States. Bent's Fort was, therefore, located at a very strategic place for international commerce. It became a headquarters for French Canadian and American fur trappers and traders who—through the American Fur Company—successfully exported beaver pelts, in the form of top hats, to the salons of Paris and London.

In the spring or early summer of 1846, during the time of US-Mexican War, Charles Bent visited Colonel Stephen W. Kearny, leader of the Army of the West at Forth Leavenworth, Kansas. Together with a large contingent of his army, Kearny gathered at Bent's Fort by the end of June in preparation to march on Santa Fe on behalf of the Government of the United States to take possession of New Mexico that belonged to the Republic of Mexico. Padre Martinez, the priest of Taos, had been a Mexican nationalist. He had been ordained a priest in Durango, Mexico a year after Mexican Independence, and considered Padre Miguel Hidalgo (Father of Mexican Independence) a hero and mentor. At the same time, he considered George Washington as another of his hero-mentors. Padre Martinez appreciated the ideals spelled out in the American Constitution and Bill of Rights. Although Padre Martinez had resisted U.S. encroachment into New Mexico since the early 1840s, he eventually came to believe that New Mexico would be better off under the flag of the United States. Before coming into Santa Fe, Kearny was aware that Padre Martinez was the main religious and political leader in northern New Mexico and throughout the whole region. Kearny, ironically, dispatched Captain Bent with a dozen soldiers to escort Padre Martinez and his brothers from Taos to Santa Fe in order to pledge allegiance to the American Flag. Because of their convictions, and in order to attempt avoiding bloodshed in the civil transfer of power, they willingly complied, thus becoming the first inhabitants of New Mexico to become citizens of the United States. Moreover, Colonel Kearny asked Padre Martinez to borrow his Ramage printing press on which the Padre had published New Mexico's first book, a newspaper, as well as religious and educational materials. The Padre lent the press to the Colonel soon-to-be promoted to Brigadier General, and Kearny used it to publish his Code of Laws.

You can say that the teachings of the American Government represent a burro, and this burro can only be mounted by lawyers and not the Clergy.

— Padre Martínez to seminary students in September 1846 when transitioning his Taos seminary to law school[citation needed]

The quote attributed to Padre Martinez about the clergyman/attorney riding the burro is from an 1877 unpublished manuscript by Santiago Valdez in Spanish belonging to the Ritch Collection housed at the Huntington Library in San Marino, California, near Los Angeles: Biografia del Presbítero Antonio José Martínez, Cura de Taos. Padre Martinez made the statement in September 1846, a few weeks after General Stephen Watts Kearny had, on August 18 in the name of the United States of America, occupied Santa Fe and all of New Mexico.

See also

editCitations

edit- ^ Etulain 2002, p. 107.

- ^ Etulain 2002, p. 127.

- ^ Etulain 2002, p. 111.

- ^ Martínez, Vicente M. "The Progeny of Padre Martinez of Taos". Fundación Presbítero Don Antonio José Martínez. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- ^ a b c Etulain 2002, p. 112.

- ^ Smith, Chuck (1996). The New Mexico State Constitution: A Reference Guide. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. xxi. ISBN 0-313-29548-4.

- ^ "New Mexico Office of the State Historian : Taos Rebellion-1847". dev.newmexicohistory.org. Retrieved 2016-04-12.

- ^ du Pont Breck, Allen. The Episcopal Church in Colorado 1860-1963 (1 ed.). Big Mountain Press. p. 23-24.

- ^ Etulain 2002, p. 116.

- ^ Etulain 2002, p. 119.

References

edit- Etulain, Richard W. (2002). New Mexican Lives: Profiles and Historical Stories. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-2433-7.

Further reading

edit- Fray Angelico Chavez (c. 1981). But Time and Chance. Sunstone Press, Santa Fe. ISBN 0-913270-95-4.

- Susan A. Roberts & Calvin A. Roberts (1989). New Mexico. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-8263-1145-8.

- Rev. Juan Romero (2006) [1976]. Reluctant Dawn, A History of Padre Martinez-Based on 1877 Biography (Second ed.). Children's Book Press. ISBN 1-4243-0810-0.

- Pedro Sánchez (1978) [1903]. Memorias Sobre la Vida del Presbítero Don Antonio José Martínez / Recollections of the Life of the Priest Don Antonio José Martínez. translation by Ray John de Aragon 1978, original Spanish edition 1903. Lightning Tree. ISBN 0-89016-045-7.

- Thomas J. Steele, S.J. (1997). New Mexican Spanish Religious Oratory 1800-1900. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-8263-1768-5.

- Santiago Valdez (1993) [1877]. Biografia del Presbitero Antonio Jose Matinez, Cura de Taos. Translated by Romero, Juan.

- Authors include E.A. Mares & Thomas J. Steele (c. 1985). New Perspectives from Taos. Millient Rogers Museum of Taos. ISBN 0-9609818-3-7.

External links

edit- Cuaderno de Ortografia From the Collections at the Library of Congress