Jerzy Kosiński (Polish pronunciation: [ˈjɛʐɨ kɔˈɕij̃skʲi]; born Józef Lewinkopf; June 14, 1933 – May 3, 1991) was a Polish-American writer and two-time president of the American Chapter of P.E.N., who wrote primarily in English. Born in Poland, he survived World War II in Poland as a Jewish boy and, as a young man, emigrated to the U.S., where he became a citizen.

Jerzy Kosiński | |

|---|---|

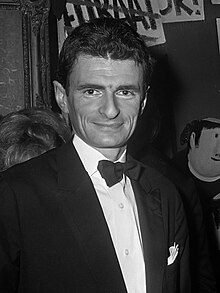

Kosiński in 1969 | |

| Born | Józef Lewinkopf June 14, 1933 Łódź, Poland |

| Died | May 3, 1991 (aged 57) New York City, U.S. |

| Education | University of Łódź |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Spouses | |

| Signature | |

He was known for various novels, among them Being There (1971)[1] and the controversial The Painted Bird (1965), which were adapted as films in 1979 and 2019, respectively.[2]

Biography

editKosiński was born Józef Lewinkopf to Jewish parents in Łódź, Poland, in 1933.[3] As a child during World War II, he lived in occupied central Poland under a false identity, Jerzy Kosiński, which his father gave to him. Eugeniusz Okoń, a Catholic priest, issued him a forged baptismal certificate, and the Lewinkopf family survived the Holocaust thanks to local villagers who offered assistance to Polish Jews, often at great risk. Kosiński's father was assisted not only by town leaders and clergymen, but also by individuals such as Marianna Pasiowa, a member of an underground network that helped Jews evade capture. The family lived openly in Dąbrowa Rzeczycka, near Stalowa Wola, and attended church in nearby Wola Rzeczycka, with the support of villagers in Kępa Rzeczycka. For a time, they were sheltered by a Catholic family in Rzeczyca Okrągła. Jerzy even served as an altar boy in the local church.[4]

As Kosiński's father aligned himself with the new communist regime in Poland, his family postwar life was relatively well-off.[5] After the war ended, Kosiński and his parents moved to Jelenia Góra. By age 22, he had earned graduate degrees in history and sociology at the University of Łódź.[6] He then became a teaching assistant at the Polish Academy of Sciences. Kosiński also studied in the Soviet Union, and served as a sharpshooter in the Polish Army.[6] His biographer said that Kosinski disliked conformity and, therefore, the communism that his father swore an allegiance to, developing anti-communist views.[5]

To migrate to the United States in 1957, he created a fake foundation, which supposedly sponsored him.[7] He later said he forged the letters from prominent communist authorities guaranteeing his loyal return to Poland, as were then required for anyone leaving the country.[7]

Kosiński first worked at odd jobs to get by, including driving a truck,[7] and he managed to graduate from Columbia University. He became an American citizen in 1965. He also received grants from the Guggenheim Fellowship in 1967 and the Ford Foundation in 1968. In 1970, he won the American Academy of Arts and Letters award for literature.[8] The grants allowed him to write a political non-fiction book that opened new doors of opportunity.[7] He became a lecturer at Yale, Princeton, Davenport, and Wesleyan universities.

Kosiński practiced the photographic arts, with one-man exhibitions to his credit in Warsaw's Crooked Circle Gallery (1957) and in the Andre Zarre Gallery in New York (1988).

In 1962, Kosiński married an American steel heiress, Mary Hayward Weir, eighteen years his senior. They divorced four years later. Weir died in 1968 from brain cancer, leaving Kosiński out of her will. He fictionalized his marriage in his novel Blind Date, speaking of Weir under the pseudonym Mary-Jane Kirkland.[7] Kosiński later, in 1968, married Katherina "Kiki" von Fraunhofer (1933–2007), a marketing consultant and a descendant of Bavarian nobility.[7]

Death

editToward the end of his life, Kosiński suffered from multiple illnesses and questions arose regarding plagiarism in his work.[9] By his late 50s, he was suffering from an irregular heartbeat.[6]

He died by suicide on May 3, 1991, by ingesting a lethal amount of alcohol and drugs and wrapping a plastic bag around his head, suffocating himself to death.[2][6] His suicide note read: "I am going to put myself to sleep now for a bit longer than usual. Call it Eternity."[9][10] Per Kosiński's wishes, Kosiński was cremated and Oscar de la Renta spread his ashes near his home in the Dominican Republic, off a small cove in Casa de Campo.[11]

Notable novels

editKosiński's novels have appeared on The New York Times Best Seller list, and have been translated into over 30 languages, with total sales estimated at 70 million in 1991.[12]

The Painted Bird

editThe Painted Bird, Kosiński's controversial 1965 novel, is a fictional account that depicts the personal experiences of a boy of unknown religious and ethnic background who wanders around unidentified areas of Eastern Europe during World War II and takes refuge among a series of people, many of whom are brutally cruel and abusive, either to him or to others.

Soon after the book was published in the US, Kosiński was accused by the then-Communist Polish government of being anti-Polish, especially following the regime's 1968 anti-Zionist campaign.[13] The book was banned in Poland from its initial publication until the fall of the Communist government in 1989. When it was finally printed, thousands of Poles in Warsaw lined up for as long as eight hours to purchase copies of the work autographed by Kosiński.[13] Polish literary critic and University of Warsaw professor Paweł Dudziak remarked that "in spite of the unclear role of its author,The Painted Bird is an achievement in English literature." He stressed that, because the book is a work of fiction and does not document real-world events, accusations of anti-Polish sentiment may result only from taking it too literally.[14]

The book received recommendations from Elie Wiesel who wrote in The New York Times Book Review that it was "one of the best ... Written with deep sincerity and sensitivity." Richard Kluger, reviewing it for Harper's Magazine wrote: "Extraordinary ... literally staggering ... one of the most powerful books I have ever read." Jonathan Yardley, reviewing it for The Miami Herald, wrote: "Of all the remarkable fiction that emerged from World War II, nothing stands higher than Jerzy Kosiński's The Painted Bird. A magnificent work of art, and a celebration of the individual will. No one who reads it will forget it; no one who reads it will be unmoved by it."[15]

Steps

editSteps (1968), a novel comprising scores of loosely connected vignettes, won the U.S. National Book Award for Fiction.[16]

American novelist David Foster Wallace described Steps as a "collection of unbelievably creepy little allegorical tableaux done in a terse elegant voice that's like nothing else anywhere ever". Wallace continued in praise: "Only Kafka's fragments get anywhere close to where Kosiński goes in this book, which is better than everything else he ever did combined."[17] Samuel Coale, in a 1974 discussion of Kosiński's fiction, wrote that "the narrator of Steps for instance, seems to be nothing more than a disembodied voice howling in some surrealistic wilderness."[18]

Being There

editOne of Kosiński's more significant works is Being There (1971), a satirical view of the absurd reality of America's media culture. It is the story of Chance the gardener, a man with few distinctive qualities who emerges from nowhere and suddenly becomes the heir to the throne of a Wall Street tycoon and a presidential policy adviser. His simple and straightforward responses to popular concerns are praised as visionary despite the fact that no one actually understands what he is really saying. Many questions surround his mysterious origins, and filling in the blanks in his background proves impossible.

The novel was made into a 1979 movie directed by Hal Ashby, and starring Peter Sellers, who was nominated for an Academy Award for the role, and Melvyn Douglas, who won the award for Best Supporting Actor. The screenplay was co-written by award-winning screenwriter Robert C. Jones and Kosiński. The film won the 1981 British Academy of Film and Television Arts (Film) Best Screenplay Award, as well as the 1980 Writers Guild of America Award (Screen) for Best Comedy Adapted from Another Medium. It was nominated for the 1980 Golden Globe Best Screenplay Award (Motion Picture).[19]

Criticism

editAccording to Eliot Weinberger, an American writer, essayist, editor and translator, Kosiński was not the author of The Painted Bird. Weinberger alleged in his 2000 book Karmic Traces that Kosiński was not fluent in English at the time of its writing.[20]

In a review of Jerzy Kosiński: A Biography by James Park Sloan, D.G. Myers, associate professor of English at Texas A&M University wrote "For years Kosinski passed off The Painted Bird as the true story of his own experience during the Holocaust. Long before writing it he regaled friends and dinner parties with macabre tales of a childhood spent in hiding among the Polish peasantry. Among those who were fascinated was Dorothy de Santillana, a senior editor at Houghton Mifflin, to whom Kosiński confided that he had a manuscript based on his experiences. Upon accepting the book for publication, Santillana said 'It is my understanding that, fictional as the material may sound, it is straight autobiography'. Although he backed away from this statement, Kosiński never wholly disavowed it."[21]

M.A. Orthofer addressed Weinberger's assertion: "Kosinski was, in many respects, a fake – possibly near as genuine a one as Weinberger could want. (One aspect of the best fakes is the lingering doubt that, possibly, there is some authenticity behind them – as is the case with Kosinski.) Kosinski famously liked to pretend he was someone he wasn't (as do many of the characters in his books), he occasionally published under a pseudonym, and, apparently, he plagiarized and forged left and right."[22]

Kosiński addressed these claims in the introduction to the 1976 reissue of The Painted Bird, saying that "Well-intentioned writers, critics, and readers sought facts to back up their claims that the novel was autobiographical. They wanted to cast me in the role of spokesman for my generation, especially for those who had survived the war; but for me, survival was an individual action that earned the survivor the right to speak only for himself. Facts about my life and my origins, I felt, should not be used to test the book's authenticity, any more than they should be used to encourage readers to read The Painted Bird. Furthermore, I felt then, as I do now, that fiction and autobiography are very different modes."[23]

Plagiarism allegations

editIn June 1982, a Village Voice report by Geoffrey Stokes and Eliot Fremont-Smith alleged Kosiński wrote The Painted Bird in Polish, and had it secretly translated into English. The report said that Kosiński's books had been ghost-written by "assistant editors", finding stylistic differences among Kosiński's novels. Kosiński, according to them, had depended upon his freelance editors for "the sort of composition that we usually call writing." American biographer James Sloan notes that New York poet, publisher and translator George Reavey said he had written The Painted Bird for Kosiński.[24]

The article found a more realistic picture of Kosiński's life during the Holocaust – a view which was supported by biographers Joanna Siedlecka and Sloan. The article asserted that The Painted Bird, assumed to be semi-autobiographical, was largely a work of fiction. The information showed that rather than wandering the Polish countryside, as his fictional character did, Kosiński spent the war years in hiding with Polish Catholics.

Terence Blacker, an English publisher (who helped publish Kosiński's books) and author of children's books and mysteries for adults, wrote an article published in The Independent in 2002:

The significant point about Jerzy Kosiński was that...his books...had a vision and a voice consistent with one another and with the man himself. The problem was perhaps that he was a successful, worldly author who played polo, moved in fashionable circles and even appeared as an actor in Warren Beatty's Reds. He seemed to have had an adventurous and rather kinky sexuality which, to many, made him all the more suspect. All in all, he was a perfect candidate for the snarling pack of literary hangers-on to turn on. There is something about a storyteller becoming rich and having a reasonably full private life that has a powerful potential to irritate so that, when things go wrong, it causes a very special kind of joy.[25]

Journalist John Corry wrote a 6,000-word feature article in The New York Times in November 1982, responding and defending Kosiński, which appeared on the front page of the Arts and Leisure section. Among other things, Corry alleged that reports that "Kosinski was a plagiarist in the pay of the C.I.A. were the product of a Polish Communist disinformation campaign."[26]

In an essay published in New York in 1999, Kosiński's sometime lover, Laurie Stieber, wrote that he incorporated passages from her letters into the revised and expanded 1981 edition of his 1973 novel The Devil Tree, without asking her. "The allegations in the Voice," wrote Stieber, "combined with what I knew to be true about the revised edition of The Devil Tree, left me with a gnawing mistrust in all aspects of our relationship. I hadn’t wavered, however, from my opinion that he was an extraordinary intellectual and philosopher, a brilliant storyteller and, yes, writer. But ego, and the fear of having his credibility strip-searched by erudite Polish or Russian editors, were behind his insistence on writing in English rather than using translators. By borrowing too greedily, Jerzy inadvertently wrote the Village Voice article himself."[27]

In 1988, Kosiński wrote The Hermit of 69th Street, in which he sought to demonstrate the absurdity of investigating prior work by inserting footnotes for practically every term in the book.[28] "Ironically," wrote theatre critic Lucy Komisar, "possibly his only true book ... about a successful author who is shown to be a fraud."[28]

Despite repudiation of the Village Voice allegations of plagiarism in detailed articles in The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, and other publications, Kosiński remained tainted. "I think it contributed to his death," said Zbigniew Brzezinski, a friend and fellow Polish emigrant.[6]

Television, radio, film, and newspaper appearances

editKosiński appeared 12 times on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson during 1971–1973, and The Dick Cavett Show in 1974, was a guest on the talk radio show of Long John Nebel, posed half-naked for a cover photograph by Annie Leibovitz for The New York Times Magazine in 1982, and presented the Oscar for screenwriting in 1982.

He also played the role of Bolshevik revolutionary and Politburo member Grigory Zinoviev in Warren Beatty's film Reds. The Time magazine critic wrote: "As Reed's Soviet nemesis, novelist Jerzy Kosinski acquits himself nicely–a tundra of ice against Reed's all-American fire." Newsweek complimented Kosiński's "delightfully abrasive" performance.

Friendships

editKosiński was friends with Roman Polanski, with whom he attended the National Film School in Łódź, and said he narrowly missed being at Polanski and Sharon Tate's house on the night Tate was murdered by Charles Manson's followers in 1969, due to lost luggage. His novel Blind Date portrayed the Manson murders.[7] In 1984, Polanski denied Kosiński's story in his autobiography. Journalist John Taylor of New York Magazine believes Polanski was mistaken. "Although it was a single sentence in a 461-page book, reviewers focused on it. But the accusation was untrue: Jerzy and Kiki had been invited to stay with Tate the night of the Manson murders, and they missed being killed as well only because they stopped in New York en route from Paris because their luggage had been misdirected." The reason why Taylor believes this is that "a friend of Kosiński wrote a letter to the Times, which was published in the Book Review, describing the detailed plans he and Jerzy had made to meet that weekend at Polanski's house on Cielo Drive."[6] The letter referenced was written by Clement Biddle Wood.[29]

Svetlana Alliluyeva, who had a friendship with Kosiński, is introduced as a character in his novel Blind Date.

Kosiński wrote his novel Pinball (1982) for his friend George Harrison, having conceived of the idea for the book at least 10 years before writing it.[30]

Bibliography

edit- The Future Is Ours, Comrade: Conversations with the Russians (1960), published under the pseudonym "Joseph Novak"

- No Third Path (1962), published under the pseudonym "Joseph Novak"

- The Painted Bird (1965, revised 1976)

- The Art of the Self: Essays à propos Steps (1968)

- Steps (1968)

- Being There (1971)

- By Jerzy Kosinski: Packaged Passion. (1973)[31]

- The Devil Tree (1973, revised & expanded 1982)

- Cockpit (1975)

- Blind Date (1977)

- Passion Play (1979)

- Pinball (1982)

- The Hermit of 69th Street (1988, revised 1991)

- Passing By: Selected Essays, 1962–1991 (1992)

- Oral Pleasure: Kosinski as Storyteller (2012)

Filmography

edit- Being There (novel and screenplay, cameo in gala scene, 1979)

- Reds (actor, 1981) – Grigory Zinoviev

- The Statue of Liberty (1985) – Himself

- Łódź Ghetto (1989) – Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski (voice)

- Religion, Inc. (actor, 1989) – Beggar (final film role)

- Nabarvené ptáče (film) (2019, orig. The Painted Bird)

Awards and honors

edit- 1966 – Prix du Meilleur Livre Étranger (essay category) for The Painted Bird[32]

- 1969 – National Book Award for Steps.[16]

- 1970 – Award in Literature, National Institute of Arts and Letters and American Academy of Arts and Letters

- 1973–75 – President of the American Chapter of P.E.N. Re-elected 1974, serving the maximum permitted two terms

- 1974 – B'rith Shalom Humanitarian Freedom Award

- 1977 – American Civil Liberties Union First Amendment Award

- 1979 – Writers Guild of America, East Best Screenplay Award for Being There (shared with screenwriter Robert C. Jones)

- 1980 – Polonia Media Perspectives Achievement Award

- 1981 – British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) Best Screenplay of the Year Award for Being There

- International House Harry Edmonds Life Achievement Award

- Received PhD Honoris Causa in Hebrew Letters from Spertus College of Judaica

- 1988 – Received PhD Honoris Causa in Humane Letters from Albion College, Michigan

- 1989 – Received PhD Honoris Causa in Humane Letters from State University of New York at Potsdam

Further reading

editBooks

edit- Eliot Weinberger Genuine Fakes in his collection Karmic Traces; New Directions, 2000, ISBN 0-8112-1456-7; ISBN 978-0-8112-1456-8.

- Sepp L. Tiefenthaler, Jerzy Kosinski: Eine Einfuhrung in Sein Werk, 1980, ISBN 3-416-01556-8

- Norman Lavers, Jerzy Kosinski, 1982, ISBN 0-8057-7352-5

- Byron L. Sherwin, Jerzy Kosinski: Literary Alarm Clock, 1982, ISBN 0-941542-00-9

- Barbara Ozieblo Rajkowska, Protagonista De Jerzy Kosinski: Personaje unico, 1986, ISBN 84-7496-122-X

- Paul R. Lilly, Jr., Words in Search of Victims: The Achievement of Jerzy Kosinski, Kent, Ohio, Kent State University Press, 1988, ISBN 0-87338-366-4

- Welch D. Everman, Jerzy Kosinski: the Literature of Violation, Borgo Press, 1991, ISBN 0-89370-276-5.

- Tom Teicholz, ed. Conversations with Jerzy Kosinski, Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1993, ISBN 0-87805-625-4

- Joanna Siedlecka, Czarny ptasior (The Black Bird), CIS, 1994, ISBN 83-85458-04-2

- Joanna Siedlecka, The Ugly Black Bird, Leopolis Press, 2018 ISBN 978-1-7335238-0-6

- James Park Sloan, Jerzy Kosinski: a Biography, Diane Pub. Co., 1996, ISBN 0-7881-5325-0.

- Agnieszka Salska, Marek Jedlinski, Jerzy Kosinski : Man and Work at the Crossroads of Cultures, 1997, ISBN 83-7171-087-9

- Barbara Tepa Lupack, ed. Critical Essays on Jerzy Kosinski, New York: G.K. Hall, 1998, ISBN 0-7838-0073-8

- Barbara Tepa Lupack, Being There in the Age of Trump, Lexington Books, 2020, ISBN 1793607184

Articles

edit- Oleg Ivsky, Review of The Painted Bird in Library Journal, Vol. 90, October 1, 1965, p. 4109

- Irving Howe, Review of The Painted Bird in Harper's Magazine, October 1965

- Andrew Feld, Review in Book Week, October 17, 1965, p. 2

- Anne Halley, Review of The Painted Bird in Nation, Vol. 201, November 29, 1965, p. 424

- D.A.N. Jones, Review of Steps in The New York Review of Books, Volume 12, Number 4, February 27, 1969

- Irving Howe, Review of Being There in Harper's Magazine, July 1971, p. 89.

- David H. Richter, The Three Denouements of Jerzy Kosinski's "The Painted Bird", Contemporary Literature, Vol. 15, No. 3, Summer 1974, pp. 370–85

- Gail Sheehy, "The Psychological Novelist as Portable Man", Psychology Today, December 11, 1977, pp. 126–30

- Margaret Kupcinskas Keshawarz, "Simas Kidirka: A Literary Symbol of Democratic Individualism in Jerzy Kosinski's Cockpit", Lituanus (Lithuanian Quarterly Journal of Arts and Sciences), Vol. 25, No.4, Winter 1979

- Roger Copeland, "An Interview with Jerzy Kosinski", New York Art Journal, Vol. 21, pp. 10–12, 1980

- Robert E. Ziegler, "Identity and Anonymity in the Novels of Jerzy Kosinski", Rocky Mountain Review of Language and Literature, Vol. 35, No. 2, 1981, pp. 99–109

- Barbara Gelb, "Being Jerzy Kosinski", New York Times Magazine, February 21, 1982, pp. 42–46

- Stephen Schiff, "The Kosinski Conundrum", Vanity Fair, June 1988, pp 114–19

- Thomas S. Gladsky, "Jerzy Kosinski's East European Self", Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction, Vol. XXIX, No. 2, Winter 1988, pp. 121–32

- Michael Schumacher, "Jerzy Kosinski", Writer's Yearbook, 1990, Vol. 60, pp. 82–87.

- John Corry, "The Most Considerate of Men", American Spectator, Vol. 24, No. 7, July 1991, pp. 17–18

- Phillip Routh, "The Rise and Fall of Jerzy Kosinski", Arts & Opinion, Vol. 6, No. 6, 2007.

- Timothy Neale, "'... the credentials that would rescue me': Trauma and the Fraudulent Survivor", Holocaust & Genocide Studies, Vol. 24, No. 3, 2010.

Biographical accounts

editHe is the subject of the off-Broadway play More Lies About Jerzy (2001), written by Davey Holmes and originally starring Jared Harris as Kosinski-inspired character "Jerzy Lesnewski". The most recent production being produced at the New End Theatre in London starring George Layton.

He also appears as one of the 'literary golems' (ghosts) in Thane Rosenbaum's novel The Golems of Gotham.

One of the songs of the Polish band NeLL, entitled "Frisco Lights", was inspired by Kosinski.[33][34]

References

edit- ^ Date of publication from Kirkus Reviews. Excerpts were published in magazines in fall 1970, confusing the publication date of the book. See https://www.kirkusreviews.com/book-reviews/jerzy-kosinski/being-there/ Archived June 27, 2023, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved February 14, 2023.

- ^ a b Stanley, Alessandra (May 4, 1991). "Jerzy Kosiński, The Writer, 57, Is Found Dead". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 25, 2012. Retrieved April 5, 2008.

- ^ Moshe Pelli: The Shadow of Death: Letters in Flames. University Press of America, 2007.

- ^ James Park Sloan. Jerzy Kosiński: A Biography (New York: Dutton/Penguin, 1996), pp.7–54.

- ^ a b Myers, D. G. (October 1, 1996). "A Life Beyond Repair". First Things. Archived from the original on May 4, 2024. Retrieved May 4, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Taylor, John. "The Haunted Bird: The Death and Life of Jerzy Kosinski Archived May 28, 2013, at the Wayback Machine", New York Magazine, June 15, 1991.

- ^ a b c d e f g Chambers, Andrea. "Because He Writes from Life—his—sex and Violence Haunt Jerzy Kosiński's Fiction". People Weekly. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved June 28, 2008.

- ^ Mervyn Rothstein (May 4, 1991). "In Novels and Life, a Maverick and an Eccentric". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 20, 2020. Retrieved February 9, 2017.

- ^ a b Breitbart, William; Rosenfeld, Barry. "Physician-Assisted Suicide: The Influence of Psychosocial Issues". Moffitt Cancer Center. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved February 27, 2011.

Jerzy Kosiński, the Polish novelist and Holocaust survivor, committed suicide in May 1991. Like other individuals suffering with chronic medical illnesses, he chose suicide as a means of controlling the course of his disease and the circumstances of his death.

- ^ Article in Newsweek, May 13, 1991.

- ^ "I Am Jerzy Kosinski". The Rupture. February 2, 2014. Archived from the original on April 9, 2024. Retrieved April 9, 2024.

- ^ "Greenwood Press advertisement". Archived from the original on July 13, 2010. Retrieved June 19, 2007.

- ^ a b "Poland Publishes 'The Painted Bird'" Archived March 20, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, April 22, 1989.

- ^ Dudziak, Paweł. JERZY KOSIŃSKI, 2003. Retrieved April 10, 2007. Polish: "Efektem kolektywnego tłumaczenia i niejasnej do końca roli samego "autora" w tworzeniu wersji ostatecznej, jest wyjątkowe pod względem językowym, wybitne dzieło literatury anglojęzycznej."

- ^ From book promotional advertisement by Barnes & Noble[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "National Book Awards – 1969" Archived October 28, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. National Book Foundation. Retrieved 2012-03-28.

(with essay by Harold Augenbraum from the Awards 60-year anniversary blog) - ^ Zacharek, Stephanie (April 12, 1999). "Overlooked". Salon. Archived from the original on July 25, 2010. Retrieved March 19, 2010.

- ^ Samuel Coale. The Quest for the Elusive Self: the Fiction of Jerzy Kosiński. Critique: Studies in Modern Fiction. 14, (3), pp. 25–37. Quoted in: Harold Bloom. Twentieth-century American Literature. Archived April 1, 2023, at the Wayback Machine. Chelsea House Publishers, 1985. ISBN 0-87754-804-8, ISBN 978-0-87754-804-1

- ^ Awards for Jerzy Kosiński at IMDb

- ^ Eliot Weinberger Genuine Fakes in his collection Karmic Traces; New Directions, 2000, ISBN 978-0-8112-1456-8

- ^ "D. G. Myers, Jerzy Kosinski: A Biography by James Park Sloan". Archived from the original on October 24, 2006. Retrieved November 12, 2006.

- ^ ""Facts and Fakes" by M.A.Orthofer". Archived from the original on October 18, 2006. Retrieved February 14, 2007.

- ^ Kosinski, Jerry (1976). The Painted Bird. Grove Press Books. xiii–xiv. ISBN 0-8021-3422-X.

- ^ George Reavey D. G. Myers, Jerzy Kosinski: A Biography by James Park Sloan Archived October 24, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Plagiarism? Let's just call it postmodernism" by Terence Blacker Archived 15 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Corry, John (November 7, 1982). "17 YEARS OF IDEOLOGICAL ATTACK ON A CULTURAL TARGET". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 4, 2019. Retrieved May 23, 2019.

- ^ Stieber, Laurie (January 4, 1999). "Her Private Devil". New York. Archived from the original on July 5, 2023. Retrieved July 5, 2023.

- ^ a b "New York Theatre Wire: "More Lies About Jerzy" by Lucy Komisar". Archived from the original on November 17, 2006. Retrieved November 12, 2006.

- ^ Wood, Clement Biddle (April 15, 1984). "Letter, 'Tate Did Expect Kosinski'". New York Times Book Review. p. 35. Archived from the original on July 7, 2019. Retrieved July 7, 2019.

- ^ Kosiński, Jerzy (1992). Passing By: Selected Essays, 1962–1991 Grove Press, p.54 ISBN 0-8021-3423-8

- ^ Kosinski, J. (1973). By Jerzy Kosinski: Packaged Passion. The American Scholar, 42(2), 193–204. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/41207100 Archived December 21, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Meilleur livre étranger | Book awards | LibraryThing". www.librarything.com. Archived from the original on December 25, 2016. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ "NeLL - Frisco Lights". www.youtube.com. November 10, 2011. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved September 16, 2021.

- ^ "Już jest! NeLL wydał nową płytę! [PL]". www.archiwum.chorzowianin.pl. Archived from the original on September 15, 2021. Retrieved September 16, 2021.

External links

edit- Jerzy Kosiński at IMDb

- Katherina von Fraunhofer-Kosinski Collection of Jerzy Kosinski. General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

- Designing for Jerzy Kosinski Archived October 19, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Jerzy Kosiński Archived July 20, 2014, at the Wayback Machine at Culture.pl

- "Jerzy Kosinski, The Art of Fiction No. 46". The Paris Review (Interview). No. 54. Interviewed by George Plimpton and Rocco Landesman. Summer 1972. Archived from the original on August 15, 2013. Retrieved November 6, 2010.