George Maciunas (English: /məˈtʃuːnəs/; Lithuanian: Jurgis Mačiūnas; November 8, 1931 Kaunas – May 9, 1978 Boston, Massachusetts) was a Lithuanian American artist, art historian, and art organizer who was the founding member and central coordinator of Fluxus,[1] an international community of artists, architects, composers, and designers. He is most famous for organizing and performing in early Fluxus Happenings and Festivals, for his Fluxus graphic art work, and for assembling a series of highly influential Fluxus artists' multiples.[2]

George Maciunas | |

|---|---|

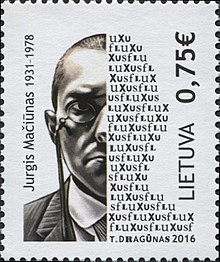

George Maciunas on a 2016 postage stamp of Lithuania | |

| Born | Jurgis Mačiūnas November 8, 1931 Kaunas, Lithuania |

| Died | May 9, 1978 (aged 46) Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Nationality | Lithuanian/American |

| Education | Architecture and Graphic Design |

| Known for | Visual Art, Aesthetics, Artist's Multiples, Installation, Music, Sculpture, Performance, Mail Art |

| Notable work | History of Art Chart (1955-1960) |

| Movement | Fluxus |

| Spouse | Billie Hutching |

Early life

editHis father, Alexander M. Maciunas, was a Lithuanian architect and engineer who had trained in Berlin, and his mother, Leokadija, was a Russian-born dancer from Tiflis affiliated with the Lithuanian National Opera[3] and, later, Aleksandr Kerensky's private secretary, helping him complete his memoirs.[4]

After fleeing Lithuania to avoid being arrested by the advancing Red Army in 1944, and living briefly in Bad Nauheim, Frankfurt, Germany, initially under Nazi control and then under the occupying forces,[5] Jurgis Mačiūnas and his family emigrated to the US in 1948, living in a middle class area of Long Island, New York.

After arriving in the US, George studied art, graphic design, and architecture at Cooper Union, architecture and musicology at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh and finally art history at New York University's Institute of Fine Arts specializing in the European and Siberian art of migrations. His studies lasted eleven years from 1949 to 1960 and were completed in succession. This began a fascination with the history of art for the rest of his life, and whilst there he began his first art-history chart, measuring 6 by 12 feet, a time/space chart categorizing all past styles, movements, schools, artists etc.[6] between 1955 and 1960. Whilst this project remained unfinished, he would publish three versions of a history of the avant-garde. The first appeared in 1966, with Fluxus as the focal point. He also began a correspondence with Raoul Hausmann, an original member of Berlin Dada, who advised him to stop using the term "neo-dada" and concentrate instead on "Fluxus" to describe the nascent movement.[7]

Duke University Professor Kristine Stiles has discussed Fluxus as part of a movement towards global humanism achieved through the breakdown of boundaries in artistic media, cultural norms, and political conventions.[8] The blurring of cultural conventions, which began in the early 20th century with movements such as Dada and Futurism, was continued by Fluxus artists in correspondence with the changes taking place in the sixties. Like the definition of "Flux", which means "to flow", Fluxus artists sought to reorder the temples of production and reveal "the extraordinary that remains latent in the undisclosed ordinary" during the midst of the dramatic modernist epoch.

Career

editPrimarily influenced by John Cage's Experimental Music Composition classes at the New School for Social Research[9] and an emerging interest in Eastern Philosophy, a number of avant-garde artists in New York were beginning to run parallel and competing Happenings at the beginning of the 1960s.[2]

As well as Maciunas' concerts at the AG Gallery in March 1961 featuring music and events by Maciunas himself, Toshi Ichiyanagi, Mac Low and Dick Higgins,[10] the two other most important precursors to Fluxus were La Monte Young's influential series of performances in the Chambers Street loft of Yoko Ono and Toshi Ichiyanagi in 1961 involving Henry Flynt, La Monte Young, Joseph Byrd & Robert Morris amongst others; and Robert Watts and George Brecht's Yam Festival, spring 1963 at Rutgers University and New York, which included a series of mail art event scores and performances by John Cage, Allan Kaprow, Alison Knowles, Ay-O, and Dick Higgins. All of these artists and more eventually became associated with Fluxus, either through their collaboration on multiples, inclusion in anthologies, or participation in Fluxus concerts'.[2][11]

Other key influences noted by Maciunas included the Happenings that had occurred at the Black Mountain College involving Robert Rauschenberg, John Cage, David Tudor, Merce Cunningham, and others; the Nouveaux Réalistes; the Concept Art of Henry Flynt and Marcel Duchamp's notion of the readymade.[2]

Though Maciunas conceived of the name "Fluxus" for a publication covering Lithuanian Culture conceived of during a meeting of Lithuanian émigrés,[12] Fluxus soon developed into much more: an avant-garde movement characterized by playful subversion of previous art traditions (even including those of previous avant-garde movements). Fluxus also soon meant Dick Higgins' famously coined term intermedia, a view that art should not-be something rarefied or commercial, and a firm commitment to blurring the distinctions between art and life. Maciunas' lifelong interest in diagrams made him chart the political, cultural and social history as well as art history and the chronology of Fluxus.

In 1963, Maciunas composed the first Fluxus Manifesto, (see above), which called upon its readers to:

...purge the world of bourgeois sickness, 'intellectual', professional & commercialized culture ... PROMOTE A REVOLUTIONARY FLOOD AND TIDE IN ART, ... promote NON ART REALITY to be grasped by all peoples, not only critics, dilettantes and professionals ... FUSE the cadres of cultural, social & political revolutionaries into united front & action.

Shared by its sibling art movements pop art and minimalism, Fluxus expressed a countercultural sentiment to the value of art and the modes of its experience –distinctly achieved by its commitment to collectivism and to decommodifying and deaestheticizing art. Its aesthetic practitioners, valuing originality over imitating overworked forms, reconceptualized the art object and the nature of performance through musical 'concerts', 'olympic' games, and publications. By undermining the traditional role of art and artist, its humor is reflective of a goal to bring life back into art, which Maciunas states in his agenda, "If man could experience the world, the concrete world surrounding him (from mathematical ideas to physical matter) in the same way he experiences art, there would be no need for art, artists and similar 'nonproductive' elements".[13]

The AG Gallery and the first Fluxus festivals

editIn 1960, whilst attending composition classes of the electronic composer Richard Maxfield at the New School for Social Research in New York, Maciunas met many of the future participants of Fluxus, including La Monte Young, Al Hansen, Allan Kaprow, and Jackson Mac Low. In 1961 he opened the AG Gallery at 925 Madison Avenue with fellow Lithuanian Almus Salcius, intending to finance the gallery's ambitious programme of events and exhibitions by importing delicatessen foods and rare musical instruments.[3] The gallery, though short-lived (it closed on July 30 due to lack of funds),[14] was devoted to new and groundbreaking art across genres and held exhibits and performance art events by many of his new acquaintances.

To avoid debt collectors, Maciunas took a job as a civilian graphic designer at a U.S. Air Force base in Wiesbaden, Germany in late 1961.[15] It was there that he organized the first Fluxus Festival in September 1962. This festival featured various "concerts," scripted actions performed by Fluxus artists, as well as interpreting a number of works by other members of the international avant-garde .

One of the most notorious events performed at Wiesbaden was Maciunas' interpretation of Philip Corner's Piano Activities, the score of which asked a group of people to 'play', 'scratch or rub' and 'strike soundboard, pins, lid or drag various objects across them.' In Maciunas' interpretation, with the help of Higgins, Williams and others, the piano was completely destroyed.[16] This event was considered scandalous enough to appear on German television four times. The festival then traveled to Cologne, Paris, Düsseldorf, Amsterdam, The Hague, and Nice.[17] These concerts and events were to become integral to the legacy of Fluxus.

The return to New York and the Fluxshop

editAfter his contract with the US Airforce was terminated due to chronic illness, Maciunas was forced to return to New York, September 1963. He began to work as a graphic artist at the New York studio of graphic designer and former Look art director Jack Marshad. He established the official Fluxus Headquarters at 359 Canal Street in New York City and proceeded to make Fluxus into a sort of multinational corporation, replete with "a complex amalgam of Fluxus Products from the FluxShop and the Flux Mail-Order Catalogue and Warehouse, Fluxus copyright protection, a collective newspaper, a Flux Housing Cooperative and frequently revised lists of incorporated Fluxus "workers".

The shop, like all his business ventures, was notoriously unsuccessful, however. In a 1978 interview with Larry Miller shortly before his death, Maciunas estimated spending 'about $50,000' on Fluxus projects over the years that would never recoup their investment.

Larry Miller, "May I ask a stupid question? Why didn't it pay off? Because isn't part of the idea that it's low cost and multiple distribution..."

GM; "No one was buying it, in those days. We opened up a store on Canal Street, what was it, 1964, and we had it open almost all year. We didn't make one sale in that whole year... We did not even sell a 50 cent item, a postage stamp sheet... you could buy V TRE papers for a quarter, you could buy George Brecht's puzzles for one dollar, Fluxus yearboxes for twenty dollars."[18]

Flux boxes

editDuring this time, Maciunas was assembling Fluxus boxes and Flux-Kits, small boxes containing cards and objects designed and assembled by artists such as Christo, Yoko Ono, and George Brecht. The first one to be planned was Fluxus 1, a wooden box filled with artworks by most of Maciunas' colleagues. Production difficulties meant that the publication date was pushed back to 1964; Brecht's Water Yam, 1963, became the first Flux box to actually be published. It was quickly followed by similar collected works of other affiliated artists, such as Ben Vautier and Robert Watts; the Fluxkit contained in an attaché case (1965–66) and another compendium Flux Year Box 2 (1966–68). There was an anthology of Fluxfilms (1966), 11 irregularly-spaced editions of the Fluxus newspaper cc V TRE edited with George Brecht[19] (1964–79) and the Fluxus Cabinet (1975–77).[2] He was also closely involved with the production of a number of Flux Chess sets.

Perhaps most important of all of Maciunas's publishing activities remain the object multiples, conceived as inexpensive, mass-produced unlimited editions. These were either works made by individual Fluxus artists, sometimes in collaboration with Maciunas, or, most controversially, Maciunas's own interpretations of an artist's concept or score. Their purpose was to erode the cultural status of art and to help to eliminate the artist's ego.[2]

Maciunas, a trained graphic designer, was responsible for the memorable packaging of Fluxus objects, posters and newspapers, helping to give the movement a sense of unity that the artists themselves often denied.[20] He also designed a series of name cards incorporating multiple fonts to characterise each of the participating artists. According to Maciunas, Fluxus was epitomized by the work of George Brecht, particularly his word event, "Exit." The artwork consists solely of a card on which is printed the words: "Word Event" and then the word "Exit" below. Maciunas said of "Exit":

The best Fluxus 'Composition' is a most non-personal, 'readymade' one like Brecht's 'Exit'—it does not require and of us to perform it since it happens daily without any 'special' performance of it. Thus our festivals will eliminate themselves (and our need to participate) when they become total readymades (like Brecht's exit) (see [1])

Some works

editWhilst Maciunas was still alive, no Fluxus work was ever signed or numbered,[21] and many weren't even credited to any artist. As such, huge confusion continues to surround many key Fluxus works; Maciunas strived to uphold his stated aims of demonstrating the artist's 'non-professional status...his dispensability and inclusiveness' and that 'anything can be art and anyone can do it.'[22] This strategy was maintained throughout his life; key works that have been assigned to him include USA Surpasses all the Genocide Records!, c1966 (see [2]), an American Flag comparing massacres in Nazi Germany, Russia and Vietnam; the Flux Smile Machine c1970 (see [3] ) in which a spring forces the mouth into a grimace, usually considered a critique on capitalist imperialism;[23] and the film 12! Big Names!, 1973 (for the poster see [4]) in which the assembled audience, having been enticed into the cinema with the promise of 12 big names, including Andy Warhol and Yoko Ono, watched a film made entirely of 12 names—Warhol, Ono etc.—filling the 20-foot-wide (6.1 m) screen, one after the other, for a duration of five minutes each.

Professional employments

editMaciunas held several prestigious professional positions as an architect and graphic designer in firms including Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, Air Force Exchanges (Europe), Jack Marshad Inc., Olin Mathieson Chemical Corporation, and Knoll Associates.

As an architect, he developed an innovative modular prototype useful in the construction of prefabricated buildings while working at Olin Mathieson's division of Aluminum Product Development and Design. He filed a patent (#2,970,676) for the invention of a structural framework for prefabricated buildings using aluminum beams and columns on January 27, 1958. Maciunas was awarded a patent (#4,545,159) for a modular building system on February 7, 1961. He used this invention towards designing a modular prefabricated mass-housing system known as Fluxhouse. Developed as an improved design to Soviet Block Housing (or Khrushchyovka), Fluxhouse was conceived in consideration to efficiency of materials, transportation, and labor to produce a cost and time effective mass-produced housing system. As an efficient modular system intended for factory production, this eco-friendly and sustainable design can be adapted to construct a single family home, a mid-rise building, or a neighborhood community with the multiplication or subtraction of units. Maciunas conceived this design as a dwelling which combines the low-cost advantages of standardization with the freedom of customization.

SoHo and the Fluxhouse Co-Operative

editAs an urban planner, Maciunas is credited as the "Father of SoHo" for developing dilapidated loft buildings and gentrifying the neighborhood with artists cooperatives known as the Fluxhouse Cooperatives during the late sixties.[24] Maciunas converted buildings into live-work spaces for and envisioned the Fluxhouse Cooperatives as collective living environments composed of artists working in many mediums. With financial support from the J.M. Kaplan Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, Maciunas began buying several loft buildings from closing manufacturing companies in 1966. The renovation and occupancies violated the M-I zoning laws that designated SoHo as a non-residential area. The zoning laws were in place to construct the Lower Manhattan Expressway, a vast highway conceived by Robert Moses which would have obliterated much of Lower Manhattan's industrial loft district. Though the Lower Manhattan Expressway was opposed by dozens of public figures and over 200 community groups, Maciuanas' efforts and the loft artists' power effectively stopped Moses, "Opposition to the expressway was going nowhere. Our whole planning board couldn't even slow it down. Then a handful of artists stepped in and stopped it cold".[25]

When Kaplan left the project to embark on other artist cooperative buildings, Maciunas was left with little support against the law. Maciunas continued the co-op despite contravening planning laws, buying a series of loft buildings to sell to artists as working and living spaces. Although it was illegal to sell the units publicly without first filing a full-disclosure prospectus with the New York State Attorney General, Maciunas ignored the legal requirements, beginning a series of increasingly bizarre run-ins with the Attorney General of New York. Maciunas began wearing disguises and going out only at night. Strategies included sending postcards from around the world via associates and friends to persuade the authorities that he was abroad, and placing razor-sharp guillotine blades onto his front door to avoid unwanted visitors. Though, like other Fluxus projects, Maciunas managed his duties without personal profit, financial disputes between the cooperatives led to problems. On November 8, 1975, an argument with an electrician over unpaid bills resulted in a severe beating, allegedly by 'Mafia thugs', which left him with 4 broken ribs, a deflated lung, 36 stitches in his head and blind in one eye. He left New York shortly after, to attempt to start a Fluxus-oriented arts centre in a dilapidated mansion and stud farm in New Marlborough, Massachusetts.

The Fluxhouse cooperatives are often cited as playing a major role in regenerating and gentrifying SoHo.[26] SoHo has since been an enclave in which contemporary art movements have developed and flourished.

Death

editPerpetually sick, Maciunas developed cancer of the pancreas and liver in 1977. He died on May 9 of the following year in a hospital in Boston. Three months before his death, he married his friend and companion, the poet Billie Hutching. After a legal wedding in Lee, Massachusetts, the couple performed a "Fluxwedding" in a friend's loft in SoHo, February 25, 1978. The bride and groom traded clothing.[27] The event was taped by video artist Dimitri Devyatkin.[28]

Fluxus is a latin word Maciunas dug up. I never studied Latin. If it hadn't been for Maciunas nobody might have ever called it anything. We would all have gone our own ways, like the man crossing his street with his umbrella, and a woman walking a dog in another direction. We would have gone our own ways and done our own things: the only reference point for any of this bunch of people who liked each other's works, and each other, more or less, was Maciunas. So fluxus, as far as I'm concerned, is Maciunas.

— George Brecht[29]

Posthumous reputation

editMaciunas remains enigmatic to this day, and his reputation still elicits strong responses both from artists and critics who have come after Fluxus, and by artists who knew him whilst still alive.

it was a special mission for George to turn up the lights on any such illusionism and he was ever out to demonstrate that the art world has no clothes. He was perhaps the toughest of all on artists, reserving his strictest judgments for those he saw as self-promoting egoists who played into the hands of "High Art" barons.

— Larry Miller[30]

Dreamer. Child. Utopian, Fascist, Christ, Democrat, Madman. A realist whose realism always needed another kind of reality. (His conceptions of reality never coincided with the accepted reality.) He was beautiful, foolish, dogmatic, charming. Impossible.

Adrian Searle, art critic for The Guardian, put it succinctly in a review of a Fluxus exhibition;

Maciunas was fascinating, talented, and by all accounts a nightmare. Like André Breton, godfather of the surrealist movement, Maciunas would invite artists, composers and even philosophers to take part in activities. He would charm them, boss them around for years, then perform summary excommunications, banishing those who displeased him..... Maciunas would take against individuals for no good reason – composer Karlheinz Stockhausen was one – and damn by association those who had anything to do with them. All this was wearying. Richard Long's walks, Gilbert and George posing as living sculptures, Sarah Lucas's early work and a million other small gestures, actions and ephemeral objects can trace their origins back to Fluxus. It was a conduit through which ideas and personalities flowed, and still flow today. Fluxus inevitably failed, and came to be seen as old hat. It was partly a problem of packaging, though Maciunas was a very good graphic designer for whom no detail was too small to be worried over. Fluxus's aim to eliminate music, theatre, poetry, fiction and all the rest of the fine arts combined was doomed. Only the mass entertainment industry might achieve such a thing.

— Adrian Searle[32]

The view that his death liberated Fluxus is also widespread;

I do believe that Fluxus not only survived George, but now that it is finally free to be Fluxus, it is becoming that something/nothing with which George should be happy.

The life of George Maciunas is subject of a documentary film by the Manhattan-based artist and independent filmmaker Jeffrey Perkins who met Maciunas in 1966. It is made out of Maciunas' friends voices, material from 44 interviews that had been gathered by Perkins since 2010 on his travels to Europe, America and Japan.[34] An oratorio loosely based on Maciunas and titled Machunas premiered in August 2005 in the St. Christopher Summer Festival in Vilnius, Lithuania.[35] Machunas was conceived by artist Lucio Pozzi, with music by Frank J. Oteri. Several of Maciunas' friends and colleagues protested the fact that the libretto was mistaken by many as a biography.

In 2024, art historian Colby Chamberlain published an indepth book on Maciunas with the University of Chicago Press called Fluxus Administration: George Maciunas and the Art of Paperwork.

Dedicated museums and collections

editMaciunas' work has been exhibited in many of the major museums around the world with archives held in The Whitney Museum of American Art, The Walker Art Center, the Getty Research Institute, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, and Kaunas Picture Gallery, representing the Fluxus room. Recently acquired from the Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection, The Museum of Modern Art currently holds the largest collection of Maciunas and Fluxus works of 10,000 items. As part of a touring exhibition organized by Dartmouth College, Maciunas' work was featured in "Fluxus and the Essential Questions of Life" at New York University's Grey Gallery in Fall 2011 and University of Michigan's Museum of Art in Spring 2012.

Despite controversy, the Stendhal gallery has held multiple exhibitions devoted to the legacy and work of George Maciunas. In 2005, they presented "To George With Love: From the Personal Collection of Jonas Mekas," which displayed original drawings, posters, objects, and other Fluxus items as well as various films from the Fluxfilm Anthology, a collection of 41 films made by Fluxus artists. In 2006, the gallery presented "George Maciunas, 1953–1978: Charts Diagrams, Films, Documents, and Atlases." In 2007, the Maya Stendhal Gallery collaborated with the city of Vilnius, Lithuania, to open the Jonas Mekas Visual Arts Center. The center's inaugural exhibition examined the lives and work of prominent figures within the history of the avant-garde, including George Maciunas. In 2008, the gallery held an exhibition devoted to Maciunas' architectural projects, in particular, a utopian housing structure Maciunas drafted in the late fifties and early sixties, entitled "George Maciunas: Prefabricated Building Systems."

In 2010 problems arose between Harry Stendhal and Jonas Mekas in which some of the practices of the Stendhal Gallery fell into question, causing concern among surviving Fluxus artists.[36] The George Maciunas/Fluxus Foundation, became active in November 2011, presenting exhibitions on the contemporary applications of Maciunas' inventions and theories regarding education and architecture. These exhibitions have explored his ideas as precursors to adaptive design processes and global networks. In September 2012, the foundation held an exhibition on Maciunas' architectural work centered on his prefabricated modular mass-housing system known as Fluxhouse.

See also

editNotes and references

edit- ^ Colby Chamberlain, Fluxus Administration: George Maciunas and the Art of Paperwork, University of Chicago Press, p. 29

- ^ a b c d e f "MoMA". MoMA.org. Retrieved May 2, 2015.

- ^ a b Mr. Fluxus, p. 338

- ^ Mr. Fluxus, p. 18

- ^ "George Maciunas". Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- ^ Mr. Fluxus, p. 31

- ^ Letter from R Hausmann, 1962 quoted in Mr. Fluxus, p. 40

- ^ Cheng, Meiling; Cody, Gabrielle H. (2016). Reading contemporary performance: theatricality across genres. London New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-62497-8.

- ^ Colby Chamberlain, Fluxus Administration: George Maciunas and the Art of Paperwork, University of Chicago Press, p. 64

- ^ Oxford Art Online; Performance Art

- ^ According to a letter written by Maciunas to Vostell in November 1964, the 'inner core' of fluxus at that time was Brecht, Ay-O, Willem de Ridder, Dick Higgins, Alison Knowles, Joe Jones, Shigeko Kubota, Takehisa Kosugi, Maciunas, Ben Patterson, Mieko Shiomi, Ben Vautier, Robert Watts, Emmett Williams, La Monte Young, with Kuniharu Akiyama listed as co-chairman for Japan, and Barbara Moore as administrator in New York. (quoted in Mr. Fluxus, p. 42)

- ^ Colby Chamberlain, Fluxus Administration: George Maciunas and the Art of Paperwork, University of Chicago Press, p. 25

- ^ "George Maciunas/Fluxus Foundation 'About'". Retrieved June 26, 2012.

- ^ Colby Chamberlain, Fluxus Administration: George Maciunas and the Art of Paperwork, University of Chicago Press, p. 60 & 63

- ^ Colby Chamberlain, Fluxus Administration: George Maciunas and the Art of Paperwork, University of Chicago Press, pp. 67-68

- ^ "Interview with Philip Corner". Archived from the original on January 1, 2015. Retrieved May 2, 2015.

- ^ The programmes for these concerts included works by John Cage, Terry Riley, Philip Corner, La Monte Young, Henry Flynt, George Brecht, Toshi Ichiyanagi, Yoko Ono, Stockhausen, György Ligeti, Alison Knowles, Emmett Williams, Benjamin Patterson, Joseph Byrd, Raoul Hausmann, Daniel Spoerri, Robert Filliou, Robert Watts, Brion Gysin, Joseph Beuys, Krzysztof Penderecki, Sylvano Bussotti, Tomas Schmit, Takehisa Kosugi, Arthur Köpcke, Wolf Vostell and Cornelius Cardew, amongst others.

- ^ Interview with Larry Miller, 1978, quoted in Mr. Fluxus, p. 114

- ^ "Fluxus & Happening – George Brecht – Books and Publications". Retrieved May 2, 2015.

- ^ Brecht, George (1964). "Something about fluxus". Fluxus Newspaper. 4. Archived from the original on 2012-02-01.

- ^ "Sims Reed – Books in Stock". Archived from the original on February 20, 2012. Retrieved May 2, 2015.

- ^ A 1965 Inventory list by Maciunas, quoted in Mr. Fluxus, p. 88

- ^ Higgins, Hannah (2002). Fluxus Experience. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-520-22867-2.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (March 15, 1992). "Streetscapes: 80 Wooster Street; The Irascible 'Father' of SoHo". The New York Times.

- ^ Stern, Robert A. M.; Mellins, Thomas; Fishman, David (1995). New York 1960: Architecture and Urbanism Between the Second World War and the Bicentennial. New York: Monacelli Press. pp. 259–277. ISBN 1-885254-02-4. OCLC 32159240. OL 1130718M.

- ^ George Maciunas. IMDb

- ^ According to Hutching, quoted in Mr. Fluxus, p. 280. Maciunas was a transvestite and masochist.

- ^ Devyatkin, Dimitri. Video. February 28, 1978.

- ^ Brecht quoted in Mr. Fluxus, p. 41

- ^ Mr. Fluxus, p. 323

- ^ Mr. Fluxus, p. 322

- ^ Searle, Adrian (December 10, 2008). "Adrian Searle on the dream of fluxus". the Guardian.

- ^ Mr. Fluxus, p. 332

- ^ "A portrait of George Maciunas". InEnArt. January 5, 2015. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- ^ "MACHUNAS". www.luciopozzi.com. Retrieved 2024-02-04.

- ^ Vartanian, Hrag (July 13, 2010) "Stendhal Gallery Owner Accused of Swindling Artists Jonas Mekas & Paula Scher". hyperallergic.com

Further reading

edit- Emmett Williams, Ann Noel, Ay-O (1998). Mr. Fluxus: A Collective Portrait of George Maciunas 1931–1978. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-97461-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Astrit Schmidt-Burkhardt, Maciunas' Learning Machines. From Art History to a Chronology of Fluxus. With a foreword by Jon Hendricks. Second, revised and enlarged edition(SpringerWienNewYork, 2011, ISBN 978-3-7091-0479-8)

- Julia Robinson, "The Brechtian Event Score: A Structure in Fluxus", Performance Research (U.K.) Vol. 7, No. 3, September 2002.

- Colby Chamberlain, Fluxus Administration: George Maciunas and the Art of Paperwork, University of Chicago Press, 2024 ISBN 022683137X

- Thomas Kellein, "The Dream of Fluxus" (Edition Hanjorg Mayer, 2007)

- Liz Kotz, "Post-Cagean Aesthetics and the Event Score" (the MIT Press, October, Vol. 95 (Winter, 2001), pp. 54–89)

- Roslyn Bernstein & Shael Shapiro, Illegal Living: 80 Wooster Street and the Evolution of SoHo (Jonas Mekas Foundation), September 2010. www.illegalliving.com ISBN 978-609-95172-0-9

- Der Traum von Fluxus. George Maciunas: Eine Künstlerbiographie. Thomas Kellein, Walther König, 2007. ISBN 978-3-8656-0228-2.

- Petra Stegmann. The lunatics are on the loose… European Fluxus Festivals 1962–1977. Down with art! Potsdam, 2012, ISBN 978-3-9815579-0-9.

Films about George Maciunas

editGeorge. Jeffrey Perkins, Documentary feature-length film/video portrait of George Maciunas, US, 2018 [1]

External links

edit- A whole series of artworks by Maciunas on We Make Money Not Art

- Sonic Youth's interpretation of Maciunas' Piano Piece #13 for Nam June Paik on YouTube

- Museum Fluxus+ Potsdam Germany

- 1962–2012 50 years Fluxus in Germany

- Museum Vostell Malpartida with Fluxus Collection

- An excellent interview with Emmett Williams about Fluxus, Maciunas and the European Avant-Garde.

- An extraordinary postcard sent to Nam June Paik, expelling him from Fluxus after performing with Stockhausen, c1965

- The Fluxus edition of Aspen on UbuWeb

- Reminiscences of meeting Maciunas, by Yoko Ono

- Fluxus Performance Workbook

- Jonas Mekas' Warhol and Maciunas, featuring Maciunas' Dumpling Party, 1971 on YouTube

- Bibliography of Maciunas material.

- George Maciunas Inerview – KRAB Radio Broadcast, Seattle, 1977 (streaming audio clips)

- Maciunas' Timeline and CV

- 37 short Fluxus films, 1962–70

- A nice archive of Flux boxes at Printed Matter

- Media Art Net archive of early Fluxus works

- A history and critique of early fluxus, especially the fluxus festorum; The Origins of Fluxus, Stuart Home

- FluxRadio an online radio programme on the Fluxus movement at Ràdio Web MACBA

- Kaunas Picture Gallery | Fluxus Room

- George Maciunas works - MoMA

- George Maciunas works - Fondazione Bonotto