14°27′36″S 28°25′34″E / 14.460°S 28.426°E

Replica (Museum Mauer, Germany) | |

| Common name | Kabwe 1 |

|---|---|

| Species | Homo heidelbergensis (Homo rhodesiensis) |

| Age | 324-274 ka |

| Date discovered | 1921 |

| Discovered by | Tom Zwiglaar |

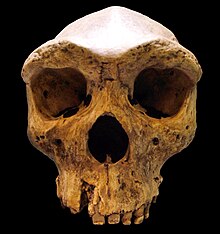

Kabwe 1, also known as the Broken Hill skull and Rhodesian Man, is a Middle Paleolithic fossil assigned by Arthur Smith Woodward in 1921 as the type specimen for Homo rhodesiensis, now mostly considered a synonym of Homo heidelbergensis.[1]

The cranium was discovered in Broken Hill mine, a lead and zinc mine in Northern Rhodesia (now Kabwe, Zambia) on 17 June 1921[2] by Tom Zwiglaar, a Swiss miner; and an African miner whose name was not recorded.[3] In addition to the cranium, an upper jaw from another individual, a sacrum, a tibia, and two femur fragments were also found. The skull was dubbed "Rhodesian Man" at the time of the find, but is now commonly referred to as the Broken Hill skull or the Kabwe cranium.

The skull is kept in the Natural History Museum, London.[4]

Discovery

editDetails of the skull's recovery were recorded by Aleš Hrdlička, an anthropologist with the Smithsonian Institution.[3] Swiss miner Tom Swiglaar and an unnamed African miner uncovered the skull on 17 June 1921 while working an ore pocket within the mine.[3] The skull was shown to the mine's managers, who photographed it being held by Swiglaar.[3] It was then examined by a doctor at Broken Hill, who recognized it as a fossil of potential scientific importance.[3] Several months later, the Rhodesia Broken Hill Mine Company shipped it to England, donating it to the British Museum in London.[3] There it was examined by paleontologist Arthur Smith Woodward and identified as belonging to a new species, then identified as Homo rhodesiensis.[3]

Date

editThe destruction of the paleoanthropological site has made stratigraphic dating impossible. Prior to the 1970s, the skull was believed to be only 30-40,000 years old.[5] In 1974, Bada et al. (1974) established a direct date of 110 ka, measured by aspartic acid racemisation.[6] The Smithsonian Institution suggested in 2010 an age between 150,000 and 300,000 years old, with an upper bound of 500,000 years suggested by animal fossils collected from the site.[7][5] A new technique applied to the skull allowed quarter-millimetre thick fragments to be removed and the skull therefore dated directly, with the new estimated age range, published in 2020, being 324,000 to 274,000 years ago.[8]

Morphology

editCranial capacity of the Broken Hill skull has been estimated at 1,230 cm³.[9] The skull suggests an extremely robust individual with the comparatively largest brow-ridges of any known hominin. It was described as having a broad face similar to that of Homo neanderthalensis (i.e. large nasal bones and thick protruding brow ridges).

The skull has cavities in ten of the upper teeth and is considered one of the oldest known occurrences of cavities. Pitting indicates significant infection before death and implies that the cause of death may have been due to dental disease infection or possibly chronic ear infection.[citation needed]

Classification

editInitially, the skull was classified as belonging to a novel species, Homo rhodesiensis, which is now generally classified as a synonym for African subspecies of Homo heidelbergensis. While the cranial volume overlaps with the range of Homo sapiens, other features such as the brain case morphology and prominent brow ridges are suggestive of older species.[3] These features have led some scientists to the conclusion that Homo heidelbergensis represents a transitional phase between the earlier Homo erectus and modern humans and Neanderthals.[3] As of 2019, no attempts to extract DNA or sequence a genome from the Kabwe skull have been successful.[3] Results of radiometric dating of matrix associated with Kabwe 1 place the age estimate of Kabwe 1 at 299,000 years old, virtually about the same age as the earliest Homo sapiens.[10] In October 2021, it was suggested the skull was a late surviving representative of the newly defined species, Homo bodoensis.[11]

Possible repatriation

editSince the 1970s, the government of Zambia has petitioned the United Kingdom for custody of the Kabwe skull, citing a number of international laws and treaties on cultural artifacts as well as colonial-era laws made by the United Kingdom.[3] According to the interpretation of the 1912 Bushman Relics Proclamation offered by the Zambian government, it was unlawful in 1921 to remove cultural relics from Northern Rhodesia without a permit from the British South Africa Company, which it maintains was not issued to the Broken Hill mining company prior to its donation of the skull to the British Museum.[3] In May 2018, at a meeting of the UNESCO World Heritage Committee, British delegates agreed to negotiations with Zambia regarding eventual repatriation of the artifact, accompanied by agreements regarding access to the skull and associated scans and digital data by researchers.[3]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Hublin, J.-J. (2013), "The Middle Pleistocene Record. On the Origin of Neandertals, Modern Humans and Others" in: David R. Begun (ed.), A Companion to Paleoanthropology, John Wiley, pp. 517-537 (p. 523).

- ^ Chambo Ng'uni (2015-01-10). "Zambia resolute on recovering Broken Hill Man from Britain – Zambia Daily Mail". Daily-mail.co.zm. Retrieved 2018-06-04. "Records at Kabwe Municipal Council reveal that the skull was discovered in Mutwe wa Nsofu area during mining excavation. The cave where the remains were found seemed to have served as a shelter and camping place for the early man. Animal bones were also discovered and they represented the remains of meals and these were predominantly of antelope. Having been discovered at Broken Hill Mine where mining started around 1904, the skull was later named Broken Hill Man. The skull was complete and its features were recognizable. It had a round perforation of the borne that could have been caused by a wooden pointed spear. Discovered along with the skull were parts of the face of the second individual, a thigh bone, shin bone, part of the bones of the pelvis, a sacrum, part of the bone of the upper arm, a quantity of animal bones, some stones and primitive bone implements."

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Balter, Michael (2019-02-18). "Zambia's Most Famous Skulls Might Finally Be Headed Home". www.theatlantic.com. The Atlantic. Retrieved 2019-02-18.

- ^ "Collections - Natural History Museum". www.nhm.ac.uk.

- ^ a b "Kabwe cranium". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ Bada, Jeffrey L., Roy A. Schroeder, Reiner Protsch, and Rainer Berger. Concordance of Collagen-Based Radiocarbon and Aspartic-Acid Racemization Ages Archived 2015-03-20 at the Wayback Machine PNAS abstract URL. Bada, J. L. (1985). "Amino Acid Racemization Dating of Fossil Bones". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 13. Arjournals.annualreviews.org: 241–268. Bibcode:1985AREPS..13..241B. doi:10.1146/annurev.ea.13.050185.001325.

- ^ "Kabwe 1". humanorigins.si.edu. Smithsonian Institution. 30 January 2010. Retrieved 2019-02-18.

- ^ Grün, Rainer; Pike, Alistair; McDermott, Frank; Eggins, Stephen; Mortimer, Graham; Aubert, Maxime; Kinsley, Lesley; Joannes-Boyau, Renaud; Rumsey, Michael; Denys, Christiane; Brink, James; Clark, Tara; Stringer, Chris (2020-04-01). "Dating the skull from Broken Hill, Zambia, and its position in human evolution" (PDF). Nature. 580 (7803): 372–375. Bibcode:2020Natur.580..372G. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2165-4. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 32296179. S2CID 214736650.

- ^ Rightmire, G. Philip. The Evolution of Homo erectus: Comparative Anatomical Studies of an Extinct Human Species Cambridge University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-521-44998-7, ISBN 978-0-521-44998-4.

- ^ Grün, Rainer; Pike, Alistair; McDermott, Frank; Eggins, Stephen; Mortimer, Graham; Aubert, Maxime; Kinsley, Lesley; Joannes-Boyau, Renaud; Rumsey, Michael; Denys, Christiane; Brink, James; Clark, Tara; Stringer, Chris (1 April 2020). "Dating the skull from Broken Hill, Zambia, and its position in human evolution" (PDF). Nature. 580 (7803): 372–375. Bibcode:2020Natur.580..372G. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2165-4. PMID 32296179. S2CID 214736650.

- ^ Roksandic, Mirjana; Radović, Predrag; Wu, Xiu-Jie; Bae, Christopher J. (2021). "Resolving the "muddle in the middle": The case for Homo bodoensis sp. nov". Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews. 31 (1): 20–29. doi:10.1002/evan.21929. ISSN 1520-6505. PMC 9297855. PMID 34710249. S2CID 240152672.