Kapiolani Medical Center for Women and Children

Kapiʻolani Medical Center for Women and Children is a Women's and Children's hospital, It is part of Hawaii Pacific Health's network of hospitals. It is located in Honolulu, Hawaii within neighborhood of Moiliili. Kapiʻolani Medical Center is Hawaii's only children's hospital with a team of physicians and nurses and specialized technology trained specifically to care for children, from infants to young adults. It is the state's only 24-hour pediatric emergency department, pediatric intensive care unit and adolescent unit. The hospital provides comprehensive pediatric specialties and subspecialties to infants, children, teens, and young adults aged 0–21 throughout Hawaii.[1][2]

| Kapiolani Medical Center for Women and Children | |

|---|---|

| Hawaii Pacific Health | |

| |

| |

| Geography | |

| Location | Honolulu, Oahu, Hawaii, United States |

| Organization | |

| Care system | Community, Specialist |

| Funding | Non-profit hospital |

| Type | Non-profit |

| Patron | Queen Kapiʻolani |

| Network | Hawaii Pacific Health |

| Services | |

| Emergency department | Yes |

| Beds | 207 |

| History | |

| Opened | 1890 |

| Links | |

| Website | http://www.kapiolani.org |

| Lists | Hospitals in Hawaii |

The facility was founded by Queen Kapiʻolani as the Kapiʻolani Maternity Home in 1890 for which she held bazaars and luaus to raise $8,000 needed to start the Home. It has since changed its name several times. Kauikeolani Children's Hospital opened in 1909 named for Emma Kauikeōlani Napoleon Mahelona (1862–1931), the wife of Albert Spencer Wilcox (1844–1919).[3] In 1978, it merged with Kapiʻolani Hospital to become Kapiʻolani Medical Center for Women and Children.[4][5][6]

Historical timeline

editKapiʻolani Hospital

edit- In 1884, Princess Victoria Kekaulike died and willed her home, Ululani, as the site of a proposed maternity home to help Hawaiian mothers.

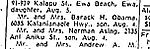

- In 1890, after the princess's sister, Queen Kapiʻolani, raised $8,000 through bazaars and luaus, she founded the Kapiʻolani Home of the Hoʻoulu and Hoʻola Lahui Society (society to propagate and perpetuate the race), located at Beretania and Makiki streets, to provide a maternity home for Hawaiian women. The five-bedroom home was opened on June 14, 1890, by King Kalākaua and Queen Kapiʻolani. Only six babies were born at the home the first year since Native Hawaiian women remained suspicious of doctors and institutions.

- In 1917, the society purchased the adjacent August Dreier property southeast of Ululani on Beretania Street.

- In 1918, the home moved to a two-story house with 25 beds at 1538 S. Beretania Street, changed its name to the Kapiʻolani Maternity Home, and opened its doors to women of other than Hawaiian descent.

- In 1927, the trustees purchased the property of Dr. John Whitney on the southeast corner of Punahou and Bingham streets to build a new maternity home.

- In 1928, groundbreaking ceremonies for the new maternity home were held on June 28.

- In 1929, the home moved on March 26 to a new larger building with 50 beds (in twenty-two private rooms, four 2-bedrooms, and two wards) located on the southeast corner of Punahou and Bingham streets and expanded its functions to include non-infectious gynecological problems. The original Whitney home was converted to a nurses' home.

- In 1931, its name was changed to the Kapiʻolani Maternity and Gynecological Hospital.

- In 1939, after purchasing the adjacent Spalding property south of the hospital on Punahou Street, the Spalding home was converted into a nurses' home named the Kekaulike Nurses' Home.

- In 1945, the hospital, at 1611 Bingham Street, finished construction of the two-story Ewa wing that doubled its capacity to 110 beds.

- In 1957, the hospital completed a new and enlarged nursery.

- In 1961, former president Barack Obama was born in the hospital on August 4.[7][8][9][10][11]

- In 1966, the hospital completed a new four-story Lani Ward Booth wing on Punahou Street, with the top two floors left as shells, capacity remained at 110 beds.

- In 1970, the hospital finished the fourth floor of the Lani Booth wing on Punahou Street, capacity increased to 138 beds.

- In 1971, its name was changed to Kapiʻolani Hospital.

- In 1974, the hospital began a major rebuilding project, adding an eleven-story hospital and medical office tower on the southeast corner of Punahou and Bingham Streets, a three-story building, and a parking structure for a combined Kapiʻolani/Children's Medical Center.

- In 1976, the new tower was dedicated and Kapiʻolani patients were moved to its second and fourth floors.

- In 1977, a section of the original 1929 building was torn down and tiles from its roof were sold to commemorate the 145,000 babies born under it from 1929 to 1977.

Kauikeolani Children's Hospital

edit- In 1908, Albert Spencer Wilcox (1844–1919) gave $55,000 and other private subscribers gave an additional $50,000 to buy several acres of land and erect a two-story comparatively small, homelike children's hospital (with preference given to Hawaiian children) at 226 N. Kuakini Street, named after Wilcox's wife, Emma Kauikeolani Napoliean Mahelona (1862–1931). A maternity service was soon after added to the hospital.

- In 1929, the maternity service at the hospital was discontinued.

- In 1950, a new, modern two-story hospital building with a capacity of 100 beds replaced the original building.

- In 1953, the Rehabilitation Center of Hawaii was established by the Kauikeolani Children's Hospital Foundation.

- In 1969, the rehabilitation center was renamed the Pacific Institute of Rehabilitation Medicine.

- In 1975, the rehabilitation center separated from Kauikeolani Children's Hospital to become the independent Rehabilitation Hospital of the Pacific, which expanded into the 1950 Kauikeolani Children's Hospital building after the latter relocated to Kapiʻolani/Children's Medical Center on September 15, 1978.

Kapiʻolani Medical Center for Women and Children

edit- In 1976, Kapiʻolani Hospital and Kauikeolani Children's Hospital began a protracted, decade-long merger.

- In 1978, Kauikeolani Children's Hospital moved into the new eleven-story (226-bed, 108-bassinet) Kapiʻolani/Children's Medical Center tower located at 1319 Punahou Street on the southeast corner of Punahou and Bingham streets—initially with separate entrances for the pediatricians on Bingham Street and the obstetricians on Punahou Street.

- In 1984, the medical staff and board of directors of the two former hospitals were merged.

- In 1986, the two former hospitals formally completed their merger.

- In 1989, Kapiʻolani purchased for $76 million the new 116-bed Pali Momi Medical Center in Aiea, built by Health Care International, six months after it opened.

- In 2001, Kapiʻolani Medical Center for Women and Children and Kapiʻolani Medical Center at Pali Momi in Aiea merged with Wilcox Memorial Hospital in Lihue on the Hawaiian island of Kauai (founded in 1938) and the Straub Clinic & Hospital (founded in 1921) on King Street, under a new parent company, Hawaii Pacific Health

- In 2024, Kapiʻolani Medical Center became the only hospital in Hawaii to lock out its nurses from their scheduled shifts. The unionized nurses, (members of the Hawaii Nurses Association,) had been out on a one-day unfair labor practice strike related to the experience of retaliation when calling out unsafe staffing levels on their shifts. The hospital claims locking nurses out is a "legal tool" to end the labor dispute and demanded the nurses accept their contract unconditionally to be let back in to work. Kapiʻolani administration and the nurses had been in negotiations over their contract for almost a year, unable to agree on appropriate staffing numbers and wages that would allow Hawaii nurses to stay in Hawaii.

References

editSources

edit- Yardley, Maili; Rogers, Miriam (1984). The history of Kapiolani Hospital. Honolulu: Topgallant Pub. Co. ISBN 0-914916-62-9.

- Schnack, Ferdinand J.H. (1915). The aloha guide: the standard handbook of Honolulu and the Hawaiian Islands. Honolulu: Honolulu Star-Bulletin. p. 150. OCLC 12657550.

- Allen, Gwenfread E. (1950). Hawaii's war years, 1941–1945. Honolulu: University of Hawaii. p. 339. ISBN 0-8371-5331-X.

- Catton, Margaret Mary Louise (1959). Social service in Hawaii. Palo Alto, Calif.: Pacific Books. pp. 99–101, 102–103, 289. OCLC 1970774.

- Lewis, Frances R. Hegglund (1969). History of nursing in Hawaii. Node, Wyo.: Germann-Kilmer. pp. 68, 104. OCLC 11323826.

- Bowers, John Z.; Purcell, Elizabeth (1978). New medical schools at home and abroad: report of a Macy conference. New York: Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation. p. 73. ISBN 0-914362-26-7.

- Lipp, Martin R. (1991). Medical landmarks USA: a travel guide to historic sites, architectural gems, remarkable museums and libraries, and other places of health related interest. New York: McGraw-Hill, Health Professions Div. pp. 310–311. ISBN 0-07-037974-2.

- "Final Environmental Assessment (FEA): Proposed improvements to Kapliolani Medical Center for Women and Children (December 2009)" (PDF). Honolulu: Office of Environmental Quality Control, Department of Health, State of Hawaii. March 8, 2010. Retrieved April 28, 2011.

- Buros, Annalisa and HNN staff. "Kapiolani Medical Center nurses locked out after one-day strike ends." Hawaii News Now, Published: Sep. 13, 2024 at 11:40 PM HST, https://www.hawaiinewsnow.com/2024/09/14/kapiolani-medical-center-nurses-brace-loss-pay-benefits-lockout-looms/. Accessed 14 September, 2024.

Footnotes

edit- ^ "What is a NICU? What is a PICU?". Hawaii Pacific Health. Retrieved 2020-12-02.

- ^ "Kapiolani - Patients & Visitors - Diamond Head Tower". www.hawaiipacifichealth.org. Retrieved 2021-08-31.

- ^ Nellist, George F., ed. (1925). "Albert Spencer Wilcox". The story of Hawaii and its builders. Honolulu: Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Retrieved September 26, 2010.

- ^ "100 years of caring for children". Honolulu: Kapiolani Health Foundation. 2009. Retrieved June 22, 2009.

- ^ Kessing, Alice (August 19, 2009). "Queen Kapi'olani's living gift to island keiki". MidWeek. Honolulu. Archived from the original on April 30, 2011. Retrieved October 1, 2009.

- ^ Hawaii Pacific Health (August 26, 2009). "Kapi'olani Hospital's '100 years – over 1 million lives' celebration". Honolulu: KGMB. Retrieved October 1, 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Maraniss, David (August 24, 2008). "Though Obama had to leave to find himself, it is Hawaii that made his rise possible". The Washington Post. p. A22. Retrieved June 28, 2009.

- ^ Serafin, Peter (March 21, 2004). "Punahou grad stirs up Illinois politics". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Retrieved June 28, 2009.

- ^ Hoover, Will (November 9, 2008). "Obama's Hawaii boyhood homes drawing gawkers". The Honolulu Advertiser. p. A1. Retrieved June 28, 2009.

Birthplaces and boyhood homes of U.S. presidents have been duly noted and honored

- ^ "Kapi' olani Health Foundation, The Centennial Dinner January 24, 2009". Honolulu: Kapiolani Health Foundation. January 24, 2009. Retrieved June 22, 2009.

- ^ Nakaso, Dan (December 22, 2008). "Twin sisters, Obama on parallel paths for years". The Honolulu Advertiser. p. B1. Retrieved March 1, 2009.